The Alexandria Retrocession of 1846

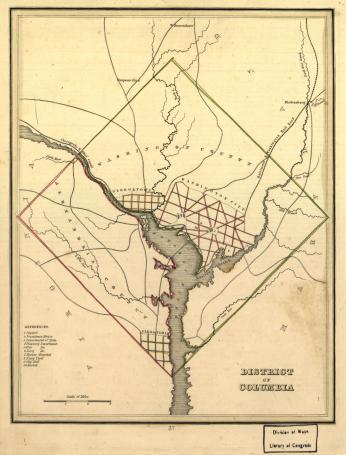

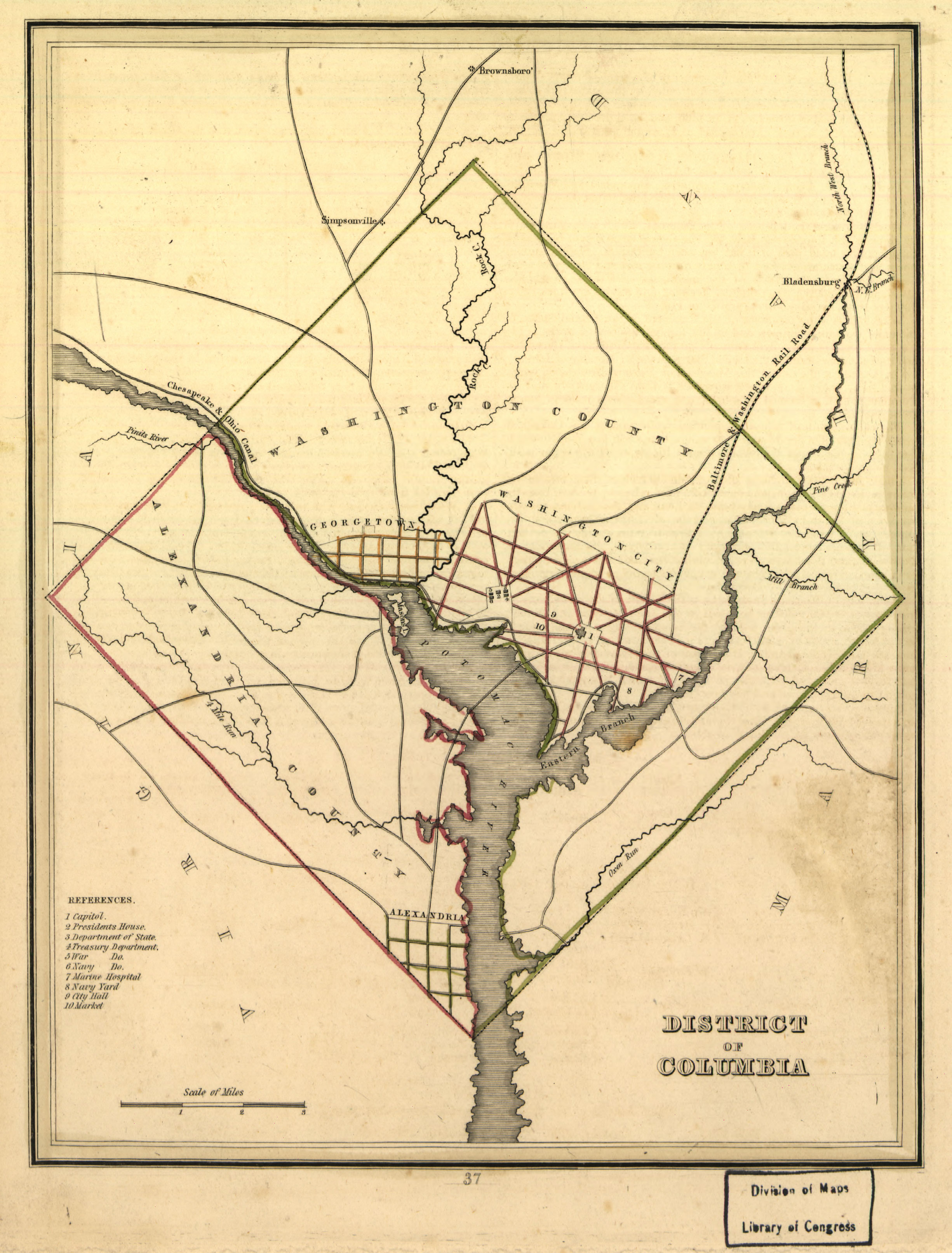

We have the states of Maryland and Virginia to thank for the land that created the nation’s capital and the greater District of Columbia. It was through their cession of territory via the Residence Act of 1790 that Congress was able to establish a permanent home for a federal government that was up to that point rather itinerant.[1]

The 100-square-mile block called for by Congress that would constitute the District was made up of 69 square miles of territory from Maryland and another 31 square miles from Virginia. The District, which was organized by the District of Columbia Organic Act of 1801, organized the territory and officially placed it under the control of Congress.[2] The bill was enacted on February 27, 1801, and almost from the moment of its passage, Virginia was looking for a way to get its territory back.

The cession of territory from Virginia resulted in the town of Alexandria being absorbed into the District. Alexandria had previously been the county seat of Fairfax County, so the state of Virginia had to move the county seat and courthouse further inland, away from the District. Additionally, Alexandria residents lost their Virginia state citizenship, and, after 1802, could no longer vote in Congressional or presidential elections.[3]

This did not sit well with those D.C. residents who fought for and supported the Revolution and the drawn out debate over the formation of the new federal government and the Constitution. The bitter irony was that these people would be living in sight of the very capitol that they could not vote to populate with their representatives.

This disenfranchisement was made worse when it became known that the mayor and key members of D.C. municipal government would in fact be appointed by the president and Congress. Additionally, an amendment to the Residence Act in 1791 prohibited the construction of public buildings anywhere other than on the Maryland side of the Potomac River.[4] This had the effect of essentially keeping the Alexandria area of D.C. as rural farmland while the Maryland side would reap much of the commercial benefits of hosting the nation’s capital.

Alexandria could not compete with nearby Georgetown or other ports for widespread commercial traffic, but it did have a thriving commercial hub for the slave trade. This terrible fact was a blight on the nation’s capital in the eyes of abolitionists in the 1820s and 1830s. They recognized that removing slavery from the Southern states was a formidable task, but it was at least a hope that the slave trade could be abolished in the District.

A series of bills were proposed in Congress beginning in 1804 to return the Alexandria portion of D.C. to Virginia. There were several groups that supported the effort at various times, and while they did not have the same interests at heart, they did have the same final goal in mind.

Just as abolitionists wanted to kick Alexandria out of the District because of slavery, pro-slavery advocates from Virginia wanted the territory back because it would add two sympathetic representatives to the state assembly. Others advocated keeping Alexandria in the District for its potential military value, though the area remained notoriously undeveloped. The federal government had forty years to build a military base there and it never did.

Debate raged for years, with some concerned that the District could not be fundamentally changed unless the Constitution was amended. Alexandria citizens repeatedly petitioned the Virginia state government and Congress to come up with a solution to the situation.

The Virginia General Assembly made the first move toward final action in February 1846 when it passed a retrocession bill. Three weeks after that, the House Committee on the District, the Congressional body that essentially governed D.C., approved the Retrocession Act and sent it to the House floor for a vote. The House passed the bill 96-65, and the Senate later concurred with a 32-14 vote. President James Polk signed the legislation returning Alexandria to Virginia on July 9, 1846.

Analysis of the final vote by historians indicates that the slave trade in D.C. and Virginia’s pro-slavery stance may not have been the deciding factor in the retrocession vote.[5]

Historian Mark David Richards writes, “the actual vote in 1846 indicates that the issue was not sharply divided along free versus slave lines. A majority of both free and slave states supported retrocession in both the Senate and the House. There were no free states in which all members voted against retrocession; in only three slave states did all members approve: Arkansas, Florida, and Louisiana. Jefferson Davis voted against retrocession and Andrew Johnson voted for it.”[6]

The biggest motivator for the citizens of Alexandria to return to their home state may have been the Constitutional neglect they experienced while being under the rule of the District of Columbia. The battle for equal representation in Congress and adequate home rule in the District would continue for decades after the retrocession of 1846. Alexandrians were the first to successfully fight for their rights, even if it meant leaving the District altogether.

Footnotes

- ^ The Residence Act of 1790 established moved the temporary capital from New York City to Philadelphia before the final location in the District of Columbia. https://www.loc.gov/rr/program/bib/ourdocs/Residence.html.

- ^ See “Chap. XV. - An act concerning the District of Columbia” for text of the law that sets up the District of Columbia. http://memory.loc.gov/cgi-bin/ampage?collId=llsl&fileName=002/llsl002.d….

- ^ “Cession and Retrocession of the District of Columbia,” Virginia Places, http://www.virginiaplaces.org/boundaries/retrocession.html.

- ^ See “Chap. XVII. – An Act to amend ‘An act for establishing the temporary and permanent seat of the Government of the United States,’” for the text of the amendment. http://memory.loc.gov/cgi-bin/ampage?collId=llsl&fileName=001/llsl001.d….

- ^ See roll call votes on retrocession broken out by free and slave states, Mark David Richards, “The Debates over the Retrocession of the District of Columbia, 1801-2004,” Washington History, Spring/Summer 2004, p. 70.

- ^ Richards, “The Debates over the Retrocession of the District of Columbia,” Washington History, p. 70.

![Sketch of the mythical fuan by Pearson Scott Foresman. [Source: Wikipedia]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2023-10/Goatman_Wikipedia_Faun_2_%28PSF%29.png?h=64a074ff&itok=C9Qh-PE1)