Wolf Trap Captures the Hearts of the DMV

Wolf Trap National Park for the Performing Arts is a mainstay of Washington, D.C.’s cultural life. The park’s large outdoor auditorium and beautiful green space play host to a variety of cultural experiences, from ballet to tap, from orchestral scores to rock concerts. But would you believe that Congressional opposition almost shut the project down before it started?

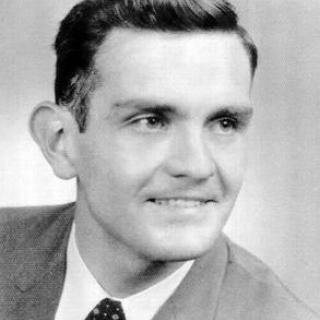

Wolf Trap was founded in 1966, gifted to the U.S. government by the former landowner, Catherine Filene Shouse.[1] Filene Shouse owned a farm in Fairfax County, Virginia, which previously played host largely to sheep. She gifted one hundred acres of her farm to the federal government, with the only caveat being that the land had to be used for a center for the arts. It was her generous gift, but even more so her tenacity and generosity of spirit in getting the park instituted that made Wolf Trap the park it is today.

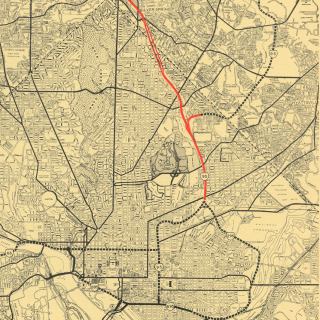

Despite the land being given free of charge, Wolf Trap wasn’t instated as a national park without a few bumps in the road. The park faced heavy enough opposition from the House of Representatives that the gift was actually voted down the first time it came to a vote.[2] A few Congressmen, including Maryland’s Charles Mathias, claimed that the D.C. area would not be able to support the park without the costly construction of more highways to accommodate the park’s guests.

The most frequent objection was "Why another cultural center?"[3] At the time, the DMV was seeing a boom in government arts centers. The Kennedy Center was in the early stages of construction, and some Congressmen worried that Wolf Trap would be too much competition for the nascent center, and that it would fail before it began. The National Symphony Orchestra was to have a new home in Columbia, MD, as well.[4] The heaviest opposition came from Maryland congressmen, who worried that the park would pull visitors from the Orchestra’s hall and the extant Merriweather Post Pavilion, which put on plays and operas with some regularity. Rep. Rogers C. B. Morton (R-MD) summed up the general concern, worrying that "suddenly we might have more facilities than we have talent."[5]

Pro-Wolf Trap Congressmen dismissed these concerns, opining that both the District’s roadways and demand for culture were already sufficient to support the new park. In September, resistance to the bill crumbled. President Johnson formally accepted the gift on Oct. 15, 1966.[6] Still, some outside Capitol Hill remained cynical about the prospective park. Alan Kriegsman of The Washington Post was among them, saying, "It remains to be seen how well the dream will work out in reality."[7]

Plans for construction began shortly after the bill was passed. As part of her bequest, Catherine Filene Shouse had also provided $1.5 million for the construction of an amphitheater on the property upon its acceptance by the government. As if Shouse hadn’t given enough, she also gave her maiden name to the amphitheater. Design and construction of the Filene Center began in 1968; Lady Bird Johnson and then-Secretary of the Interior Stewart Udall broke ground on the site that May.[8] After digging the first shovel of earth, Udall said, “Kay, I don’t think it’s a fair exchange. You gave us a farm and I give you a shovel.”

Less than four months before performances were scheduled to begin, the Filene Center suffered a fire, causing $10,000 worth of damage.[9] Undeterred, Shouse was on site every day at 7 a.m. providing coffee and donuts for the workers; she even offered all the workers free tickets to a Wolf Trap event of their choice, which many eagerly accepted.[10] It’s impossible to know whether or not this affected the speed of construction, but we do know that repairs were completed in time for the season opener on July 1.

The first season of Wolf Trap was star-studded, with the New York City Opera Company, the Cleveland Orchestra, violinist Itzhak Perlman, and the German Stuttgart Ballet all arriving to visit during the season.[11] On July 4, 1971, Wolf Trap held Independence-themed festivities, with fireworks and performances by various military outfits, including the U.S. Air Force Band, the Singing Sergeants Chorus, and the Airmen of Note (described as “the official dance orchestra of the Air Force.”)[12] The first month’s schedule included, oddly enough, a ballet production of the ever-popular Romeo and Juliet. Early attractions also included audience-participation operas, in which the course of the plot was determined by audience input.[13]

Many considered Wolf Trap to be a “pilot project” for other cultural parks by the NPS.[14] Unfortunately, despite national parks like Glen Echo having artists within them, no other park in the U.S. is dedicated to arts on the same scale. Wolf Trap remains unique in the District and among America’s national parks, serving the public need for culture and green space at the same time and place.

For more information about the park’s history, visit Wolf Trap’s official website.

Footnotes

- ^ http://www.wolftrap.org/about/history.aspx. Filene Shouse was the spouse of politician Jouett Shouse, former chair of the DNC; sadly, he passed away in 1968, before Wolf Trap had reached completion.

- ^ Katherine Gresham, “Mathias Reviews His Vote Against Cultural Park Offer,” Washington Post, October 8, 1966, p. B2.

- ^ Alan M. Kriegsman, “A National Cultural Park,” Washington Post, May 5, 1968, p. K7.

- ^ “House Rejects Wolf Trap Farm Gift,” Washington Post, September 20, 1966, p. C1.

- ^ Robert L. Asher, “Fairfax Cultural Park Bill Clears House Unit,” Washington Post, July 16, 1966, p. B1.

- ^ “President Signs Wolf Trap Bill,” Washington Post, October 16, 1966, p. B6.

- ^ Alan M. Kriegsman, “A National Cultural Park,” Washington Post, May 5, 1968, p. K7.

- ^ Paul Hume, “First Lady Breaks Ground for Wolf Trap Center,” Washington Post, May 23, 1968, p. C18.

- ^ The Filene Center, as one might expect from a giant wooden amphitheater, is somewhat prone to fires: there was another in 1982.

- ^ Paul Hume, “The Woman Who Built Wolf Trap,” Washington Post, July 1, 1971, p. C1.

- ^ Jean Battey Lewis, “Opening Season at Wolf Trap,” Washington Post, March 14, 1971, p. G1.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Ibid.

![Sketch of the mythical fuan by Pearson Scott Foresman. [Source: Wikipedia]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2023-10/Goatman_Wikipedia_Faun_2_%28PSF%29.png?h=64a074ff&itok=C9Qh-PE1)