Books You Should Read: Alexander Shepherd Biography by John Richardson

For John Richardson, Washington’s influential territorial governor, Alexander Robey “Boss” Shepherd, has been a source of fascination for over 30 years, since the author moved into D.C.’s Shepherd Park neighborhood. As he described it, “Shepherd had built his out of town house about 200 yards from where we lived at the time. The house no longer exists but the land was bought by the Lynchburg Development Company and they built Shepherd Park out of it. There is now a school that is named after Shepherd. And, I just was curious. I thought this was a very interesting character and I wanted to write about him.”

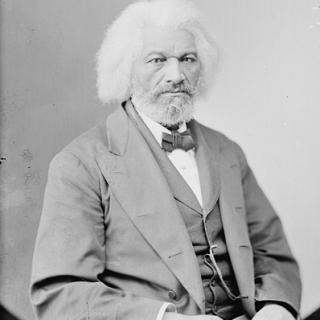

Balancing this curiosity with a day job in the CIA and stints overseas meant that progress on the book was slower than Richardson intended. But, the result of his labors is worth the wait for local history enthusiasts. Richardson’s biography, Alexander Robey Shepherd: The Man Who Built the Nation’s Capital (Ohio University Press, 2016) is a thoroughly researched and well-written study of a man who, despite his enormous impact on the District of Columbia, has not gotten the attention he deserves from scholars.

Richardson sat down with Boundary Stones to offer an overview of the book. Check out the video below!

Up through the Civil War, Washington was a pretty scraggly place. There were a few public buildings and some private homes but infrastructure was woefully inadequate. As Richardson put it, “in the wintertime it was muddy and horrible and in the summertime it was dusty and horrible. Just sort of take your pick based on the seasons.” Congress had shown little interest in funding improvements in the city. Furthermore, the District was divided into three separate jurisdictions – Washington City, Washington County, and Georgetown – each with its own government that operated under the thumb of Congress.

By the late 1860s, the ever-ambitious Shepherd (who had built up his plumbing and gas fitting business to the point where he was the fourth wealthiest Washingtonian), was pushing a vision of a unified D.C. government, with a measure of autonomy to undertake public improvements on a large scale.

He and allies sold the vision to Congress, which passed the Organic Act of 1871. The statute created a unified territorial government for the entire District of Columbia. It also created a Board of Public Works, with far-reaching powers. Shepherd was appointed to head that Board and hit the ground running. Operating at breakneck speed, he sought to build up Washington’s infrastructure and make the city worthy of its status as the national capital. His approach was, to say the least, controversial. Under Shepherd’s leadership – first as public works chairman and later as the Governor – the District government moved quickly to lay sewer lines, grade streets, pave roads, and generally modernize Washington.

The city transformed almost overnight. But, critics raised concerns about the cost and financing of the projects and accused Shepherd of corruption. According to Richardson, nay sayers “were not opposed to seeing a beautiful city developed, but they were totally opposed to seeing it done on credit, with bonds, with loans, borrowed money. And so, by 1872 there was the first of two major Congressional investigations into the affairs of the District really targeting Shepherd. And then there was a second investigation, even more lengthy, in 1874. Both investigations took endless testimony, all of which is available in verbatim reports of which I have copies and they are fascinating. But no documentable evidence—persuasive evidence—was ever provided that showed that Alexander Shepherd was personally corrupt.”

Still, by 1874, the District was in dire financial straits. Congress pulled the plug on the territorial government experiment, and took back direct control of the city’s affairs. Once again a private citizen, Shepherd tried to rebuild his career as a businessman but was unsuccessful. He declared personal bankruptcy in 1876 and left Washington a few years later.

One of the distinctive features of Richardson’s book is his lengthy discussion of Shepherd’s post-Washington life. In 1880, the former governor relocated his family to a remote area of Mexico, where he purchased a silver mine. There, he hoped to rebuild his fortune and reputation so that he could eventually make a triumphant return to Washington. As it turned out, however, that dream would not be realized. Shepherd lived out the remaining 22 years of his life in Mexico, dying there in 1902.

Shepherd’s legacy is complicated. As Richardson told us, “I think Alexander Shepherd’s lasting legacy is the physical city of Washington. Not the buildings but everything that made possible and worthwhile the construction of the physical city. I mean the McMillan Plan of 1901-1902, ‘The City Beautiful,’ – that could not have happened unless Shepherd built the infrastructure when he did.” However, the author noted, “there was a major social cost.” Following the territorial government’s dissolution, it would be 100 years before Washington regained home rule.

![Sketch of the mythical fuan by Pearson Scott Foresman. [Source: Wikipedia]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2023-10/Goatman_Wikipedia_Faun_2_%28PSF%29.png?h=64a074ff&itok=C9Qh-PE1)