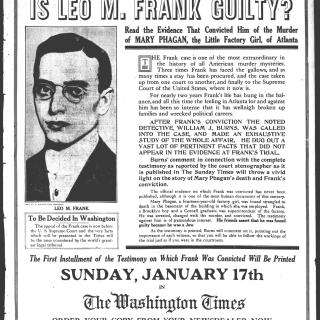

A Thwarted Protest at the Soviet Embassy

During the Cold War, as one might imagine, protests outside the Soviet Embassy were a common occurrence. But one particular protest outside the 16th St NW building stands out—both for its creativity and for an odd response by the local D.C. police.

The sight was innocuous. On August 24, 1973, about 20 D.C. Jewish school children gathered around the Embassy holding onto basketballs.[1] It was around noon, and they were getting ready to bounce the balls—presumably, loudly enough for the Soviet officials to hear—for the next 15 minutes or so. But the D.C. police, they were about to find, wasn’t going to have any of it.

Wearing sweatshirts and basketball jerseys that read “WHC,” for Washington Hebrew Congregation, and holding onto balls that had the words “Go Go Israel” painted onto them, the children were protesting recent events at the World University Games, hosted that year in Moscow.[2] Throughout those games, Israeli athletes found themselves taunted and jeered at, often by Soviet soldiers. And the Soviet government, critics said, was at best ignoring this behavior.

The controversy began when the Soviet Union decided to invite Palestinian leader Yasser Arafat, a man at that point known for targeting Israeli citizens in violent attacks as part of a plan to make Palestine politically independent from Israel, as a special guest. Critics of the Soviet Union’s treatment of Israel viewed this to be an anti-Zionist and anti-Semitic attack on Israel, and an endorsement of terrorism. “What sport other than the sport of killing does Arafat represent?” Rabbi Joshua Haberman, of the Washington Hebrew Congregation, wrote about the Soviets’ decision to invite Arafat to the Games in a Washington Post op-ed.[3]

But the tension hardly stopped there. In every game that Israel played, the athletes and Soviet Jews who supported them faced screams and taunts. Whenever the Russian Jews chanted “Go, go Israel” in a game against Brazil, the soldiers “raised a chorus of whistles and jeers,” according to the Washington Post.[4] In Israel’s game against Puerto Rico, fans yelled racial slurs at Soviet Jews who dared to root for Israel. Soldiers ripped up an Israeli flag and destroyed a banner that read“Success to Israel.”[5]

The scene deeply disturbed a woman on the Danish basketball team, who was nearly in tears when she talked to a reporter and said, “That was very ugly.”[6] And it disturbed children of the Committee for Soviet Jewry in Washington, D.C. “It was the kids who really got mad,” said Irene Manekofvsky, an officer of the Committee for Soviet Jewry. “They thought the jeering and name-calling was an injustice.”[7]

One high school student, 17-year-old Danny Haberman, decided to do something about it. Every day at noon, the Committee for Soviet Jewry held a noontime vigil, where they would stand silently as a group for fifteen minutes as a quiet protest of Soviet anti-Semitism. But Haberman had a twist: Instead of a silent vigil, he and a group of children would bounce basketballs across from the Soviet Embassy.[8]

Before the protest got underway, the police stopped the children. According to a contemporary report from the Washington Post, the District of Columbia had rules forbidding people from displaying “any flag, banner, placard or device to intimidate, coerce or bring into public odium any foreign government.” Because the children were protesting a foreign government (the Soviet Union) with a “device” (a basketball), the local children were in violation of the code.[9]

Years later, the protest would have been made legal. In a 1988 Supreme Court ruling, Justice Sandra Day O’Connor stated that this so-called “display clause” in the D.C. Code violated the First Amendment of the Constitution.[10]

But for the time being, the children had to follow the law or risk being arrested. They agreed to abide by the police’s restrictions and stashed their basketballs in the lobby of the nearby Philip Morris Building. Then they decided, instead of bouncing their basketballs, they would hold a vigil outside the Embassy—just as the Committee for Soviet Jewry had done every day for the past three years.[11]

Footnotes

- ^ “20 Protest Treatment Given Israeli Team,” Washington Evening Star, 25 August 1973.

- ^ Marjorie Hyer, “Police Bar ‘Basketball Protest,’” Washington Post, 25 August 1973.

- ^ The biographical information about Arafat comes from “Who Was Yasser Arafat?” Al Jazeera America, 6 November 2013. The rest comes from Rabbi Joshua Haberman, “Anti-Semitic Hooliganism’ in Moscow: Prelude to the Olympics?” Washington Post, 11 September 1973, ProQuest.

- ^ Associated Press, “Soviet Soldiers Jeer Israelis,” Washington Post, 20 August 1973, ProQuest.

- ^ News Dispatches, “Jewish Fans Are Attacked at Contest,” Washington Post, 22 August 1973, ProQuest.

- ^ Associated Press, “Soviet Soldiers Jeer Israelis.”

- ^ “20 Protest Treatment Given Israeli Team.”

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Hyer, “Police Bar ‘Basketball Protest.’”

- ^ Boos v. Barry, 485 U.S. 312 (1988), Legal Information Institute, Cornell University Law School.

- ^ Hyer, "Police Bar 'Basketball Protest.'"

![Sketch of the mythical fuan by Pearson Scott Foresman. [Source: Wikipedia]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2023-10/Goatman_Wikipedia_Faun_2_%28PSF%29.png?h=64a074ff&itok=C9Qh-PE1)