The Howard University Fight Over Vaccination

Prior to 1909, Harry Bradford had almost never landed himself in the paper. He appeared in The Washington Post once, when it announced that the Kensington Orchestra was going to be performing in the near future. (Bradford played violin.)[1] But other than that, nothing. And yet, in 1910, Bradford’s name was in all caps on the front page of the Post. “Bradford told to quit,” the headline read.[2]

It was a striking turn of events for the Howard University mechanical drawing instructor who had formerly lived in relative obscurity. But the story shouldn’t have come as a surprise. As the leader of the anti-vaccine movement, Bradford stood at the opposite end of his employer on one of the most significant issues in the history of American medicine.

By the turn of the 20th century, vaccination had the overwhelming support of American institutions as a lifesaver and a public health necessity. The American Medical Association strongly endorsed vaccines and favored laws that required people to vaccinate.[3] A few states and municipalities had put into place variants of these “compulsory vaccination laws,” including the District of Columbia, which required that all public school children immunize and that all children attend school.[4]

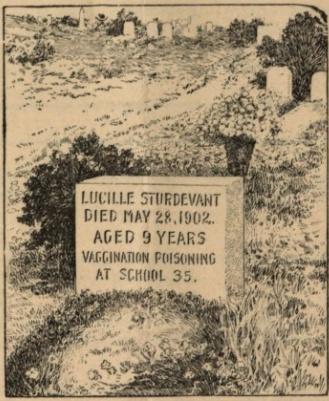

But vaccination was a risky procedure at the time, sometimes inducing infections and even death, and vaccines and the compulsory laws surrounding them had many fierce opponents.[5] In the 1890s, poor people by and large resisted vaccines, fearing they were being poisoned.[6] Due to decades of medical experimentation on slaves—Thomas Jefferson, for instance, tested smallpox immunization on several of his slaves before vaccinating his family—African Americans were especially skeptical of vaccines and frequently, like working class white people, refused to follow compulsory vaccination laws.[7]

Meanwhile, middle class, educated white people—many of whom worked as doctors in alternative medicine—began forming societies to overthrow the laws, arguing that compulsory vaccination laws were an unacceptable expansion of government power.[8] In D.C., Bradford, a white college instructor from Kensington, Maryland who does not appear to have had any previous medical instruction, stood at the center of this fight.

Calling vaccinations a “disease-grafting industry” and a “filthy fad,” Bradford, a director of the Antivaccination League of America, set out to eliminate D.C.’s compulsory vaccination law.[9] In March 1910, Bradford became the president of a newly created group called the Washington Anti-vaccination Society. In its first meeting, that society announced that it was going to raise money to sponsor a case that would test the legality of D.C.’s compulsory vaccination laws, according to a front-page story in the Washington Post.[10]

The Washington Anti-Vaccination Society quickly grew and found itself with one such case to bring to the D.C. Supreme Court (which is now the U.S. District Court for the District of Columbia). In September, the group sponsored the case of Charles Castle, whose eight-year-old daughter was denied entry into public school because he refused to vaccinate her.[11]

The case was unlikely to succeed. Five years earlier, a landmark U.S. Supreme Court case, Jacobsen v. Massachusetts, determined that compulsory vaccination laws were constitutional.

Still, Bradford’s decision to challenge D.C.’s laws did not sit well with Howard University President Rev. Wilbur Thirkield. According to Thirkield, Howard University had no problem with Bradford criticizing vaccines. “Liberty of belief and expressed opinion on religious, social, moral, and scientific questions is, of course, allowed,” Thirkield said in a statement.[12] But leading a “crusade” against vaccines apparently crossed the line. “Mr. Bradford has been informed that he must either cease taking an active part in this crusade or give up his instructorship,” the Post reported.[13]

Thirkield was particularly disturbed, he said, because Bradford worked for a historically black college and his anti-vaccination stance could bolster skepticism of vaccines among African Americans:

The school of medicine, with its more than 1,000 alumni, is looked to as the medical adviser and guide of millions of colored people. For a member of the university faculty to be published as the leader of a crusade for antivaccination not only involves the university in the bringing of possible discord into the public schools of the District, but may have a disquieting and even dangerous influence over multitudes of colored people, especially throughout the South.[14]

But there was something bigger on Thirkield’s mind: the reputation of Howard’s medical school. For the past fifty years, Howard University’s medical department had struggled financially, barely surviving. Between 1873 and 1890, professors received almost nothing in salary.[15] By the beginning of the 20th century, teacher pay was better, but Howard still struggled to sufficiently fund its medical department. It could receive little money from its students, who tended to come from poor families who couldn’t afford tuition, or its alumni, who were not wealthy enough to give large amounts of money to its endowment.[16]

Standards in medicine were rising rapidly, putting enormous pressure on schools across the country to improve their facilities and faculty salaries. Historically black institutions, with little ability to raise funds, were under particular strain. By 1923, there were only two black medical colleges—Howard and Meharry Medical College—remaining, compared to 10 in 1900.[17]

In order to cover the costs of improving and maintaining Howard’s medical department, Thirkield needed a $500,000 endowment.[18] And the vast majority of that money was going to have to come from some of the most ardent defenders of vaccines: wealthy white people who supported “regular” (as opposed to alternative) medicine.

Thirkield, in other words, was under immense pressure to come strongly to the defense of vaccines. And so he did—to the extent of publicly criticizing one of his instructors.

In the days following the Post story, both Bradford and Thirkield tried to back away from the conflict. Thirkield stated that he would continue to object whenever Bradford “publicly [identified] with the active anti-vaccination propaganda” but “what form this objection might take…I, of course, can not state.” Bradford, meanwhile, stated that he never meant any harm to Howard University. He, however, refused to say whether or not he would continue to speak out in the future. “I don’t know whether, if the university objects, I will continue an active fight against vaccination or not,” he stated.[19]

Bradford soon did decide to continue the anti-vaccination fight. In early November 1910, attorneys for the society filed court documents requesting that the nine-year-old son of D.C. resident Dr. G.W. Harris be admitted into school, despite having not been vaccinated.[20] Bradford was listed as the president of the Anti-Vaccination Society in the contemporary report by the Washington Post. Thirkield, perhaps in order to defend his instructor’s academic and personal freedom, does not appear to have commented on that case.

In January 1911, the D.C. Supreme Court ruled that D.C.’s compulsory vaccination and education laws were legal.[21] Bradford continued working at Howard but his days were numbered. In October 1910—during the original, heated conflict—F.D. Scott, the secretary of the Anti-Vaccination Society, encouraged Bradford to resign from Howard, saying that the 15,000 anti-vaccination proponents in the area could afford to pay a salary for Bradford to be president of the Anti-Vaccination Society.[22] In October 1911, Bradford took him up on their offer.[23]

In the aftermath, Thirkield went on record that Howard did not force Bradford to resign. Bradford himself declined to comment for the Post’s story on his resignation. But certainly to Charles Darr, the president of the Personal Liberty League, which stood against compulsory vaccination laws, the resignation was connected to the previous year’s conflict. “Prof. Bradford has just informed me that while he did not leave the university because of the vaccination controversy, he felt much freer now that his resignation was in,” Darr said. “We will take every means possible for fighting the law, because we feel that vaccination is wrong from every possible standpoint.”[24]

Footnotes

- ^ “Kensington,” The Washington Post, 11 November 1906. ProQuest.

- ^ “Stands by Vaccine: Howard University Takes Hand in Practice. Bradford Told to Quit,” The Washington Post, 3 October 1910. ProQuest.

- ^ Michael Willrich, Pox: An American History (New York: The Penguin Press, 2011), 259.

- ^ Karen Walloch, “’A Hot Bed of the Anti-Vaccine Heresey’: Opposition to Compulsory Vaccination in Boston and Cambridge, 1890-1905” (PhD dissertation, The University of Wisconsin-Madison, 2007), 33; Carl Harris, a Minor, by George R. Harris, His Next Friend, v. William Cox et al., Supreme Court of the District of Columbia, 39 Washington Reporter 104 (1911).

- ^ Walloch, “A Hot Bed of the Anti-Vaccine Heresey,” 58.

- ^ Willrich, Pox, 88.

- ^ Harriet Washington, Medical Apartheid: The Dark History of Medical Experimentation on Black Americans From Colonial Times to Present (New York: Harlem Moon, 2006), 59.

- ^ Willrich, Pox, 256.

- ^ “Vaccine Fight On, Society is Formed to Fight Practice in District,” Washington Post 21 March 1910.

- ^ “Vaccine is Attacked, English Lecturer Denounces Inoculation for Smallpox,” Washington Post 25 February 1909.

- ^ “Vaccine War On Today,” Washington Post 19 September 1910. I found the fact that the D.C. Supreme Court changed its name from “Records of District Courts of the United States,” National Archives, accessed 9 November 2016, https://www.archives.gov/research/guide-fed-records/groups/021.html.

- ^ “Stands by Vaccine,” Washington Post.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Walter Dyson, Howard University, the Capstone of Negro Education: A History, 1867-1940 (Washington, D.C.: Graduate School, Howard University, 1941), 245.

- ^ Tom Savitt, “Abraham Flexner and the Black Medical Schools,” Journal of the National Medical Association 98, no. 9, September 2006, 1416.

- ^ Ibid., 1415.

- ^ Ibid., 1420.

- ^ “Not Asked to Quit: No Action Taken in Case of Instructor Bradford,” Washington Evening Star, 3 October 1910.

- ^ “Attack Vaccine Law: Opponents Seek to Mandamus Board of Education,” Washington Post, 1 November 1910.

- ^ Carl Harris v. William Cox et al.

- ^ “Want Bradford’s Services: University Instructor Valuable to Anti-Vaccination Advocates,” Washington Evening Star 10 October 1910.

- ^ “Quits Howard University: Instructor H.BV. Bradford Resigns to Renew Antivaccination War,” Washington Post 26 October 1911.

- ^ Ibid.

![Sketch of the mythical fuan by Pearson Scott Foresman. [Source: Wikipedia]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2023-10/Goatman_Wikipedia_Faun_2_%28PSF%29.png?h=64a074ff&itok=C9Qh-PE1)