"More Tons, Less Huns": World War I Shipbuilding in Alexandria

“We have been waiting for lightning to strike Alexandria for a century,”[1] proclaimed Virginia Representative C.C. Carlin on December 11, 1917 as he confirmed to an anxious crowd of Alexandrians that a permanent shipyard will be built in their city.

Congressmen Carlin’s weather-related metaphor echoed sentiments shared by many residents who had long-dreamed of re-establishing Alexandria as one of the busiest and most prosperous ports in the United States—as it had been in the late 18th and early 19th century.[2] As reported in the Alexandria Gazette:

All have waited long and patiently for capitalists to appreciate the advantages offered by Alexandria. While Norfolk, Newport News and other Virginia cities have been forging ahead we have bided our time. All rejoice that the commercial importance of Alexandria is now assured and within the next few months’ operations on our river front will enthuse us as nothing has heretofore in our history.[3]

World War I fueled this rapid buildup in industrial production, and, in particular, merchant shipbuilding. America needed cargo vessels—fast—and, as luck would have it, Alexandria was prepared. Between 1910 and 1912, the Army Corps of Engineers had infilled a 46-acre bay and wildlife preserve – Battery Cove – near Jones Point Lighthouse.[4] The land’s proximity to the Potomac River and its enormous size made it an ideal site for shipbuilding.

In late 1917, Groton Iron Works of Connecticut—a subsidiary of the U.S. Steamship Company—leased the Battery Cove site for five years as a shipbuilding plant.[5] Groton signed a contract with the U.S. Shipping Board Emergency Fleet Corporation (e.g. the Federal Government), which stipulated that a new Alexandria shipyard would be constructed at Jones Point and it would produce “twelve metal vessels of 9400 DW tons, each to cost $1,504,000.00.”[6] The first ten ships were due by the end of 1918.

In early 1918, the government contract was transferred to a separate branch of the U.S. Steamship Company called the American Shipbuilding Corporation, which was subsequently renamed the Virginia Shipbuilding Corporation.

Newspapers advertised for mechanics, engineers and laborers to work at the Virginia Shipbuilding Corporation and 1,500 qualified men quickly answered the call,[7] including a sizeable contingent of Nordic immigrants from Denmark, Norway, Sweden, and Finland.[8]

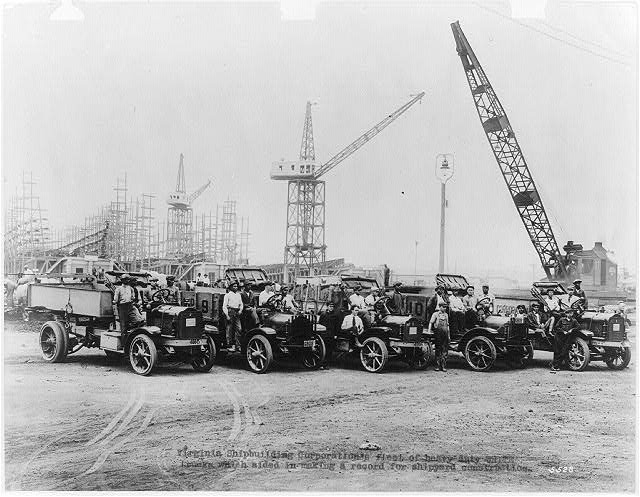

Jones Point transformed almost overnight as the company began constructing a complex for 7,000 employees, complete with production and administrative facilities, worker barracks, a company hospital, and cafeteria.[9]

At a special event on March 19, General Manager B.W. Morse stressed the crucial nature of the work happening in Alexandria, “Fellow workers: We are engaged in a patriotic work. But I fear that we do not realize its great importance…. The success of the war depends in very great measure upon ships with which to transport the men to fight across the water.”[10]

Around the same time, the Virginia Shipbuilding Corporation announced a patriotic motto/slogan contest with the promise that the winning submission would be illuminated on a mammoth sign near the shipyard.[11] There was also a reward of ten dollars. The company was swamped with thousands of suggestions for weeks, and announced the winning phrase on April 4, 1918 – “More Tons, Less Huns,” entered by Mrs. I. F. Fornshill.[12]

While patriotism was a unifying force, accommodating the sudden influx of new workers presented definite challenges for Alexandria. As the Gazette noted:

The sudden advent in our city of thousands of strangers. . . together with many automobiles and auto trucks have, at times, caused congestions at certain points. . .While the great mass of our people are overjoyed to see such animated scenes in our city, a few—very few—have taken offense at the temporary parking of automobiles and trucks in front of their property, or property in which they are interested.[13]

But, as Morse reminded the community, “Our interests are interlocking. You need industrial enterprises for ‘Greater Alexandria’ and we need ‘Greater Alexandria’ for our industrial enterprises – to feed, clothe, amuse, and house the army of employees.”[14]

With a shortage of available housing in the city, citizens were asked to rent out rooms in their homes while the shipbuilding plant was under construction.

“An urgent appeal has been made to owners of unoccupied houses to list them at once with real estate brokers, and persons who will rent rooms in their residences or take the men as boarders are requested to notify the secretary of the chamber of commerce.” -- The Washington Post, January 27, 1918. [15]

In preparation for the newcomers, the welcoming committee and social activities board of Alexandria organized social events for the shipbuilders. The Alexandria Red Cross, the Welfare Department and other organizations prepared weekly dances, intermural baseball games and theatrical events.[16] Meanwhile, the city scrambled to make infrastructure improvements and provide services to the new residents.

Construction on the twelve contracted vessels began with a bang. On May, 30, 1918, the Virginia Shipbuilding Corporation gave President Woodrow Wilson the honor of driving in the first rivet in the first steel ship to be built at the shipyards. According to an account later republished by the Historical Society of Fairfax County:

Mr. Carlin. . . escorted the President and Mrs. Wilson upon the gayly decorated concrete where the keel plate was in readiness to be placed in position. Workmen soon had the red hot rivet ready . . . The pneumatic gun, as it termed was placed in the President’s hands and as he pressed his thumb on the trigger the loud rat-a-tat-tat of the little trip hammer announced that the rivet was being speeded home.”[17]

The first lady had the pleasure of christening the first ship the Gunston Hall named after the home of colonial-era Virginia politician, George Mason.[18]

Months later, a crowd of over 10,000 onlookers waving American Flags, cheered as the Gunston Hall glided into the Potomac, taking to the water “as if she were in her element.”[19] It was the first ship to be completed at Alexandria’s new shipyard—an impressive accomplishment of engineering and teamwork.

Unfortunately, it was almost five months late.

The original contract had called for the Virginia Shipbuilding Corporation to deliver its first vessel by October 7, 1918. But, when the Gunston Hall sailed away from the shipyard, the calendar read February 27, 1919. Successive ships were similarly delayed in construction, and World War I—which had brought the shipyard to Alexandria—was over by the time any of the Alexandria-built vessels hit the water.[20] The days were numbered for shipbuilding at Jones Point. While the plant limped along for a few more years, it closed for good in 1921.

During its short history, the Virginia Shipbuilding Corporation was plagued by constant construction delays which contributed to its eventual failure. But there were other reasons, too.

Since many able-bodied, skilled laborers were fighting in World War I, there was a critical shortage of skilled workmen at industrial plants in America. Reports of Alexandria’s housing shortage by Virginia Shipping Corporation employees might have discouraged additional workers to apply for available jobs.[21] Most significantly, between March 28, 1919 and September 12, 1921, three fires at the shipyard caused over $60,000 worth of damage ($832,540.93 in 2015).[13] These three disasters lead to crucial work stoppages.

Administrative and financial problems added to the troubles at the shipyard. In October 1918, a U.S. Shipping Board examiner, so shocked by the inefficiency of the shipyard, ordered that, “No more contracts shall be given to the Virginia Shipbuilding Corporation.”[22] Only nine of the 12 ships originally contracted were ever built.

On April 11, 1921, the Virginia Shipbuilding Corporation’s financial problems came to a head and the company filed for bankruptcy.[23] Later in 1921, the Federal Government accused the ship company of fraud and financial impropriety and a contentious court battle ensued. In February 1922, the court indicted eleven senior Virginia Shipbuilding Corporation officers with conspiracy to defraud the government in connection with war contracts.[24]

In retrospect, the Virginia Shipbuilding Corporation began as a dynamic and potentially economically significant enterprise for Alexandria during the World War I era. Although the corporation did successfully make nine steel ships, Alexandrians and shipyard investors who had hoped the business would bring notoriety and economic security to their town were ultimately disappointed. Shipbuilding along the banks of the Potomac River in the early 20th century was more of a “wartime” ‘boom’ than a lasting commercial industry.

Footnotes

- ^ “Good News for All.” Alexandria Gazette, December 12, 1916. Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress. Accessed December 19, 2017. http://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn85025007/1917-12-12/ed-1/seq-2/

- ^ “The Alexandria Waterfront.” National Park Service https://www.nps.gov/gwmp/learn/historyculture/alexandria.htm

- ^ “Boundaries of Plant.” Alexandria Gazette, December 13, 1917. Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress. Accessed December 19, 2016. http://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn85025007/1917-12-13/ed-1/seq-1/

- ^ Tilp, Frederick "Shipbuilding Alexandria." The Alexandria Historical Society, 1987. P. 59-60

- ^ Lease Shipyard Site.” Alexandria Gazette December 21, 1917. Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress. Accessed December 19, 2016. http://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn85025007/1917-12-21/ed-1/seq-1/

- ^ Tilp, Frederick “Shipbuilding in Alexandria.” The Alexandria Historical Society,1987. P.59-60

- ^ Miller, Michael T. “Groton Iron Works and the Virginia Shipbuilding Corporation” Yearbook: The Historical Society of Fairfax County, VA Volume 21 1986-1988. P. 58

- ^ "Nordic Immigrants Work" http://immigrantalexandria.org/nordic-immigrants-in-alexandria-va/nordi…

- ^ "The Alexandria Waterfront." https://www.nps.gov/gwmp/learn/historyculture/alexandria.htm

- ^ "Hundreds of Employees at the Shipyards Hear Patriotic Address Today at Noon." Alexandria Gazette, March 19, 1918. Chronicling America:Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress. Accessed December 19, 2016. http://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn85025007/1918-03-19/ed-1/seq-1

- ^ Alexandria Gazette, March 4, 1918. Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress. http://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn85025007/1918-03-04/ed-1/seq-1

- ^ "More Tons, Less Huns." Alexandria Gazette, April 4,1918.Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress. Accessed on December 19, 2016. http://chronicling america.loc.gov/lcn/sn85025007/1918-04-04/ed-1/seq-1

- a, b "Problems Which Alexandria Must Solve" Alexandria Gazette, March 9, 1918.Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress. Accessed December 19, 2016. http://chronicling america.loc.gov/lccn/sn85025007/1917-12-12/ed-1/seq-1

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ The Washington Post, January 27, 1918

- ^ Alexandria Gazette, March 28, 1918. Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress. Accessed December 19, 2016. http://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn85025007/1918-03-28/ed-1/seq-1/

- ^ Miller, Michael T. "Grotton Iron Works and the Virginia Shipbuilding Corporation" Yearbook: The Historical Society of Fairfax County, VA Volume 21 1986-1988. P. 56

- ^ Ibid. 57

- ^ Ibid. 59

- ^ Ibid.55

- ^ "Problems Which Alexandria Must Solve" Alexandria Gazette, March 9, 1918.Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress. Accessed December 19, 2016. http://chronicling america.loc.gov/lccn/sn85025007/1917-12-12/ed-1/seq-1

- ^ Tilp, Frederick “Shipbuilding in Alexandria.” The Alexandria Historical Society,1987. P. 60

- ^ Ibid. 61

- ^ Miller, Michael T. "Grotton Iron Works and the Virginia Shipbuilding Corporation" Yearbook: The Historical Society of Fairfax County, VA Volume 21 1986-1988. P. 60

![Sketch of the mythical fuan by Pearson Scott Foresman. [Source: Wikipedia]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2023-10/Goatman_Wikipedia_Faun_2_%28PSF%29.png?h=64a074ff&itok=C9Qh-PE1)