The Merry Affair

When Thomas Jefferson took office in 1801, he decided he was going to do away with all the courtly nonsense of his predecessors, George Washington and John Adams. No longer would there be rules and regulations dictating behavior in social situations; not a single whiff of pomp or circumstance would be found in his administration, no sir- or should we say no pal!

Jefferson chose to implement his new policy of what he called “pell-mell” (French pêle-mêle) in a really unfortunate way: to humiliate and enrage the British legation to Washington.[1] Because that’s good foreign policy, right?

The trouble began when British minister Anthony Merry presented himself to Jefferson on November 28, 1802, dressed fully for the occasion in a “deep blue coat with black velvet trim and gold braid, white breeches, silk stockings, ornate buckled shoes, plumed hat” with a large sword at his side. Jefferson showed up, late, in worn-out slippers and “pantaloons, coat, and under-clothes indicative of utter slovenliness and indifference to appearances and in a state of negligence actually studied.”[2] As Merry gave his prepared speech to the president, Jefferson tossed a slipper up and down in the air with one foot.

Poor Merry was utterly scandalized by the meeting and further so when Secretary of State James Madison informed him that he would be expected to make the first social call to the Cabinet members. This went against all established rules of conduct! Head spinning, Merry accepted this bitter pill and looked forward to settling down in the capital and hopefully finding more familiar modes of behavior in future interactions. He visited the Cabinet members and hoped to put this business behind him.

It was only three days later that the next insult was flung in the British minister’s face. Merry and his wife, Elizabeth, were invited to dine in the White House with Jefferson and a select few others. Merry assumed, not unnaturally, that this dinner was in honor of him. It was then extra awkward when he arrived and found that Louis Andre Pichon, the French charge d’affaires, has also been invited to dinner. Jefferson had invited the diplomats of warring countries to the same party. Even today, this is a huge faux pas. It was later even revealed that Jefferson hadn’t made this bone-headed decision by accident; he had specifically written to Pichon and asked him to cut his vacation short to attend.

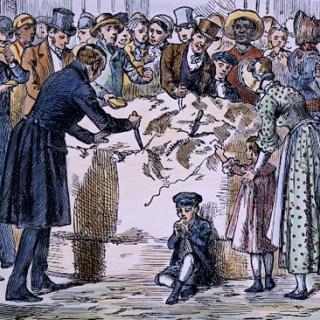

The true insult came later when the guests were called to dinner. Given all accepted standards of behavior for the era, Jefferson (the host) ought to have escorted Mrs. Merry first into the dining room. Next Mr. Merry would have escorted in the hostess, Dolly Madison. Other guests would then proceed into the dining room in order of precedence, taking seats down the table from most important to least. However, Jefferson chose to escort the woman nearest to him, Mrs. Madison. Mr. Madison entered the dining room next, escorting Mrs. Merry. Guests continued to pair off and Anthony Merry became increasingly frustrated, eventually entering the dining room by himself to find a seat. He attempted to sit as far up the table as possible, going for a seat next to the Spanish minister’s wife- the spot was snagged by a congressman at the last second.

After the dinner, Merry sent an official dispatch home to ask what he should do about Jefferson’s unbelievable rudeness. Merry minced no words and described the American situation as “the excess of the democratic ferment in this people is conspicuously evidenced by the dregs having got up to the top.”[3]

The third came after Merrys accepted a dinner invitation from the Madisons. Again, when it was announced that guests should proceed to the dining room, the host (Madison) took the arm of the woman nearest him, wife of the Secretary of the Treasury Hannah Gallatin. Guests paired off in this way while the Merrys stood, waiting for someone, anyone, to choose to escort Elizabeth into the dining room. No one did. Anthony Merry was forced to escort his own wife into the dining room. The couple marched up to the head of the table and forced Mrs. Gallatin to move so that Elizabeth could sit next to Madison.

Anthony Merry asked around the capital and discovered that this kind of radical social behavior had not been adopted before the Merrys arrived in the district, leading him to conclude that it had been specifically adopted to insult him. In a letter to a friend, Merry wrote that the insult was “from design and not from ignorance or awkwardness (though God knows a great deal of both as to mattes of even common etiquette is to be seen at every step.)”[4]

Not receiving any official instructions on how to respond, the couple implemented their own private protest against the insult of Jefferson’s pell-mell. They refused all future social invitations, refusing to go to or hold social engagements. hey additionally persuaded the Spanish minister, Marquis de Casa Yrujo, to join them in their social boycott.

This was a huge problem because the bulk of business done between two countries in this era was hammered out at social occasions, and the freeze out by the Merrys and de Casa Yrujo meant that Americans couldn’t officially treat Britain or Spain. James Madison frantically worked on damage control to end the boycott, while Jefferson showed contempt for it, stating “I shall be highly honored when the King of England is good enough to let Mr. Merry come and eat my soup.” Jefferson and the cabinet drew up a set of formal rules in 1804, the “Cannons of Ettiquitte,” trying to give legitimacy to the pell mell with ink and paper. Their misspelling of “canon” as “cannon” probably did not help their case.

As all of the District’s scandals, the boycott eventually faded away, as did the pell mell. The Merrys remained in Washington until 1806 and gave lavish parties, strictly following etiquette, and political big wigs attended with no issues. It can’t be said that the “Merry Affair” had no lasting effects, however. Merry was considered an ally to early conspirators against the US government (including Aaron Burr), and many scholars think the War of 1812 lasted twice as long as it needed to because of Merry’s correspondence with England leading up to the conflict.

More flies with honey, we guess.

Sources:

Allgor, Catherine. Parlor Politics: In Which the Ladies of Washington Help Build a City and a Government. (University of Virginia Press, 2002).

“Dolly Madison – Political Partner.” Montpelier.org.

Earman, Cynthia D. “Remembering the Ladies: Women, Etiquette, and Diversions in Washington City, 1800-1814.” Washington History, 2000.

Stanton, Lucia. “Dinner Etiquette.” Monticello.org

Footnotes

![Sketch of the mythical fuan by Pearson Scott Foresman. [Source: Wikipedia]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2023-10/Goatman_Wikipedia_Faun_2_%28PSF%29.png?h=64a074ff&itok=C9Qh-PE1)