Paleontologist in Chief: Thomas Jefferson’s Quest for the Mastodon

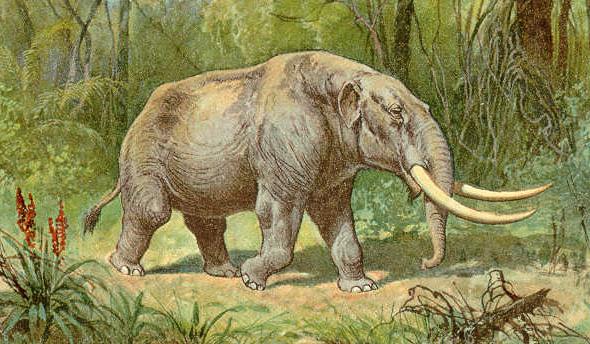

Twenty-six thousand years ago, a young male mastodon studies the glacial landscape of Ice Age Kentucky, weighing his options for dinner. He could paw through several feet of snow for another meal of bland, flattened grass. Or he might head for tasty fresh vegetation growing around a sinkhole nearby, thawed by hot spring water below.

He chooses the spring, not realizing that the ground beneath him is extremely slick shale. During dinner, he slips into the sinkhole. Weighing ten tons, it is impossible for him to climb the steep sides. The sinkhole becomes his grave. Over millennia, mud and sediment cover his bones—and the bodies of many other animals who met the same fate—forming a huge fossil deposit. Not until the 1790s will this mastodon reappear, and when he does, he will become the pièce de résistance of a bitter intellectual battle waged by none other than Thomas Jefferson.

Following the Revolutionary War, America was struggling to find international footing among the European states. The country was still considered something of a backwater, and by the late 1700s there were attempts to prove this fact scientifically. In his hefty Histoire Naturelle, leading French naturalist Count Georges Louis Leclerc laid out evidence to explain why North American species (including humans) were weaker and smaller than those from the Old World.

“No American animal can be compared with the elephant, the rhinoceros, the hippopotamus… the lion, the tiger, &c,” he wrote.1 America was simply too cold and wet to prosper. This extended to species transplanted across the Atlantic, too—American dogs, cattle, and horses became more pathetic than their European cousins. Leclerc’s “theory of American degeneracy” became conventional wisdom among European elites. It was scientific, elegantly argued, and conveniently anti-egalitarian. If the American environment fostered weaker creatures, surely its democratic experiment would also yield paltry results.

American leaders and diplomats were insulted, but also horrified by the degeneracy theory. If America was to be taken seriously in political, diplomatic, and economic matters that would allow the nascent nation to establish itself on the world stage, Leclerc's ideas had to be dispelled.

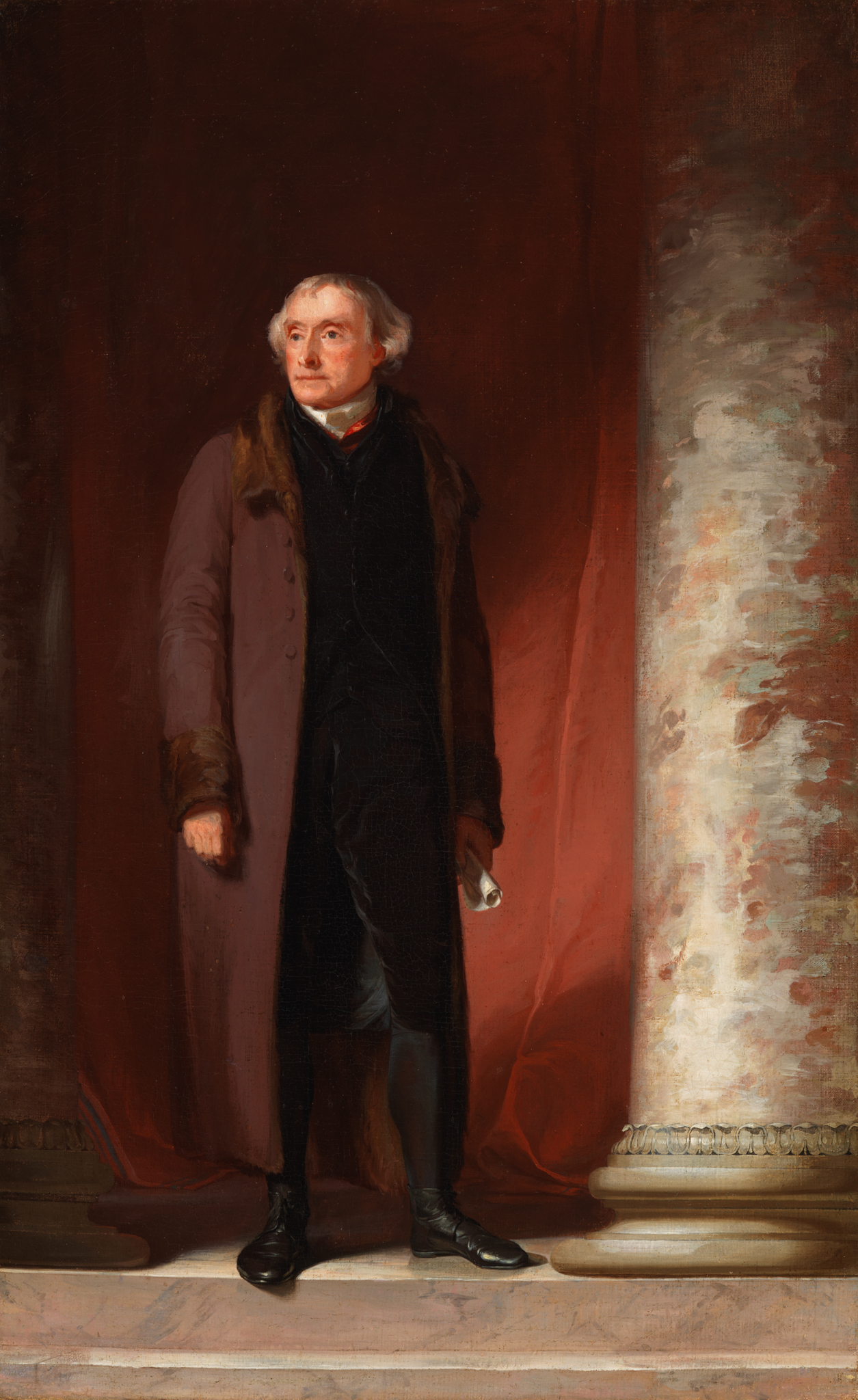

One of the most vocal dissenters was Thomas Jefferson. The Virginia statesman, who had once written that science was his “passion, politics, [and] duty,” did not plan on quietly accepting Leclerc’s slander.2 Always interested in natural history, Jefferson had recently taken interest in monstrous bones found in New York and at Big Bone Lick (the prehistoric Kentucky sinkhole). Farmers and naturalists unearthed bones unlike any animal anyone had ever seen: “ribs like rafters” and fierce conical molars as big as bricks.3

The animal was called the incognitum. Similar remains had been uncovered in Siberia, so Jefferson and other scientists assumed the incognitum was another type of mammoth. It was not until 1806 that Georges Cuvier identified it as a separate species: “mastodon” from the Greek mastos (“breast”) and odont (“tooth”).

To Jefferson, the “mammoth” was the best solution to the degeneracy theory. It was massive evidence against Leclerc’s assertions (mastodons were 9.5 feet tall at the shoulder and weighed about 8 tons) and sending a taxidermized specimen to the Count’s doorstep would be the ultimate trump card. Though the last mastodon had died about 13,000 years prior, contemporary religious and scientific theory in the early 1800s denied the possibility of extinction, and Jefferson thought similarly. Ergo, if he had evidence that the mastodon had once existed, then it was still out there, likely roaming the unexplored West. Capturing it would prove once and for all that America was not puny, not pathetic, and not to be trifled with. In the future, Jefferson would send explorers to search for the creature. Until then, he set about attacking Leclerc with the evidence he had on hand.

His first volley came in Notes on the State of Virginia, a massive treatise on law, society, politics, and natural history. In it, Jefferson discussed the fauna of North America, refuting Leclerc’s claims and snidely but correctly suggesting that the Frenchman had never “measured, weighed, or seen,” the animals he had written about in Histoire Naturelle. In one chapter, he compiled a table of American animals weighed against their Old World counterparts. Jefferson let the numbers speak for themselves, and they were squarely in favor the American bears, beavers, and mice.

In Notes, Jefferson also dedicated space to his beloved mammoth. “The skeleton,” he wrote, “bespeaks an animal of five or six times the cubic volume of the elephant.” Surely, this American giant was “the largest of all terrestrial beings.” It reigned at the top of his comparison table, with no European equivalent. Nature, which had never “permitted any one race of her animals to become extinct,” clearly commanded her creative force powerfully in America, and the mammoth’s mere existence was all the evidence Europeans should have needed.4 Quite literally, Jefferson threw the book at Leclerc and the degeneracy theory.

It didn’t stick. Leclerc was unimpressed, and degeneracy theory endured.

Until he captured a real mammoth (or at least excavated a full skeleton), Jefferson attempted to sway Leclerc with other North American animals. On a 1784 trip to Paris, he packed “an uncommonly large” panther skin and presented it to the Count.5 Three years later, he followed up with an entire bull moose. Due to amateur conservation and shipping mishaps, it arrived in poor shape and with a separate pair of antlers improvised onto its head. Nonetheless, Leclerc was impressed with the animal, seven feet tall at the shoulder, and promised Jefferson that he would “set these things right” in the next edition of the Histoire Naturelle.6 Unfortunately, this was not to be: he died six months later.

Cheated of a printed retraction, Jefferson still dreamed of his ultimate trophy: a living mastodon. As president, he continued his search for the massive creature wherever he found traces of it. According to an 1885 Magazine of American History article, even as Congress deliberated the contested presidential election between him and Aaron Burr, Jefferson was busy penning letters to his friend and fellow mastodon enthusiast Caspar Wistar, who had unearthed a new mastodon skeleton in New York.7

As Commander in Chief, though, Jefferson found himself finally with the resources to command a serious westward expedition. Once Congress approved Lewis and Clark’s journey west in 1803, the president entrusted them with his mastodon mission. In Lewis’ instructions, he wrote that “objects worthy of notice” should be reported to Washington, including “animals of the country,” especially any which “may be deemed rare or extinct.”8

Jefferson did not mention mastodons by name, but Meriwether Lewis would have known they were on his mind. A decade before, as Secretary of State, Jefferson had supported another proposed expedition West led by French botanist André Michaux. In his detailed instructions to the would-be explorer, he said that under his “Animal history” goals, the “Mammoth is particularly recommended to your enquiries.”9 In preparation for the expedition, Lewis was also tutored in anatomy and fossils by Caspar Wistar, who had so monopolized Jefferson’s attention with his mastodon excavation amid the drama of the 1800 election.

In fact, one of Lewis’ stops on his way to meet Clark in 1803 was Cincinnati, where he sent Jefferson a group of fossils from Big Bone Lick, Kentucky, and wrote a detailed report of the excavation there. Among the mastodon bones were “grinders” (molars), the “upper portion of a head,” and a “tusk of an immence size… 180” pounds.10 Unfortunately for Jefferson, the boat carrying the fossils had an accident and buried them anew in the Mississippi river muck.

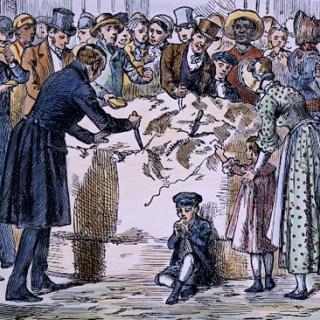

Undeterred, Jefferson continued his search. In 1797, the American Philosophical Society had formed a “Bone Committee” to “collect information [on] the past and present state of this country.”11 With Jefferson at its head, the committee’s first priority was to “procure one or more entire skeletons of the Mammoth” for study and display.12 In 1807, he sent William Clark back to Big Bone Lick to collect more specimens, particularly for head and foot bones missing from the mastodon skeleton the Society was assembling.

Clark’s visit was immensely successful. He shipped back more than 300 bones to Jefferson, including a full cranium. Jefferson carefully laid them out on the floor of the East Room of the White House like a massive jigsaw puzzle. These bones helped “in the recovery and reconstruction of the first nearly complete [mastodon] skeleton, which became a national sensation.”13

Thanks to Clark, Jefferson ended up with so many duplicate specimens that he sent three boxes of bones to the National Institute of France, which went on to become core parts of the Museum of Natural History in Paris. The rest were divided between the Philosophical Society and Monticello. Later visitors to Jefferson’s home recorded seeing “upper and lower jawbones, tusks, thigh bones, a head, and teeth of the "mammoth",” which Jefferson displayed in a special cabinet.14

Of course, neither Lewis nor Clark ever caught sight of live mastodons during their travels, though Jefferson ended up with more mastodon bones than he knew what to do with. This continued failure must have flagged the president’s hopes after so many years. In 1823, still without his mastodon, Jefferson wrote to John Adams: “Stars, well known, have disappeared… comets…may run foul of suns and planets.” Then, he conceded, “certain races of animals are become extinct.”15

Jefferson did not mention the mastodon by name, but he mounted no more expeditions to search for the beast. Just a few years earlier, Georges Cuvier (the same naturalist who had identified American “mammoths” as the separate species mastodon) established extinction as scientific fact. The American degeneracy theory faded away as the United States entered global politics and grew in territory and economic power. It seemed Jefferson’s ultimate dream would not be realized, but in the process he had amassed a rich natural history collection and helped American paleontology take its first steps.

In fact, Jefferson’s tireless pursuit of continental megafauna to prove Leclerc wrong may have also been the first example of a different aspect of the burgeoning country’s national identity: in America, everything is always bigger!

Footnotes

- 1

George Louis LE CLERC (Count de Buffon.). (1791). Buffon’s natural history abridged. T. Tegg, Cheapside, & R. Griffin, Glasgow.

- 2

Oliver, J. W. (1943). Thomas Jefferson--Scientist. The Scientific Monthly, 56(5), 460–467.

- 3

Conniff, R. (2009, June). When Thomas Jefferson Visited Yale. Yale Alumni Magazine.

- 4 Jefferson, T. (1787). Notes On the State of Virginia. M.L. & W.A. Davis--for Furman & Loudon. Pp. 65-78.

- 5

- 6

Wulf, A. (2016, March 7). Thomas Jefferson’s quest to prove America’s natural superiority. The Atlantic.

- 7 Hartnagel, C. A., & Bishop, S. C. (1922). The mastodons, mammoths and other pleistocene mammals of New York State: Being a descriptive record of all known occurrences. University of New York.

- 8

Jefferson, T. (20 June, 1803). IV. Instructions for Meriwether Lewis. Founders Online.

- 9

Jefferson, Thomas. “Letter to Andrew Michaud,” Jan. 23, 1793.

- 10

Jefferson, Thomas. “Letter from Merriwether Lewis,” Oct. 3, 1803.

- 11

Thomas Jefferson’s Monticello - Official website. (n.d.). Thomas Jefferson’s Monticello. Retrieved December 19, 2023.

- 12

American Philosophical Society, Transactions of the American Philosophical Society (Philadelphia: The Society, 1799), pg. 37.

- 13

Conniff, R. (2009, June). When Thomas Jefferson Visited Yale. Yale Alumni Magazine.

- 14

Thomas Jefferson’s Monticello - Official website. (n.d.). Thomas Jefferson’s Monticello. Retrieved December 19, 2023.

- 15

Jefferson, Thomas. “Letter to John Adams,” April 11, 1823.

![Sketch of the mythical fuan by Pearson Scott Foresman. [Source: Wikipedia]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2023-10/Goatman_Wikipedia_Faun_2_%28PSF%29.png?h=64a074ff&itok=C9Qh-PE1)