Lost from History: Josias Wilson King

Josias Wilson King is a name that would probably not ring any bells. In fact, even when Google-searched, it takes a great amount of effort to find much if anything about him. In life, however, he interacted with some of the most prominent men in American history – Presidents Thomas Jefferson and James Madison – was involved in the first scandal in the Library of Congress’ history, and helped to save America’s keystone documents.

Born in 1771 in Prince Georges County, Maryland, Josias and his family shortly moved to the town of Port Tobacco, a once booming port city and a hub of trade amidst the agrarian society of southern Maryland. The misfortune of death befell the King family, putting added pressure on Josias to provide for a growing list of dependents, which included his recently widowed sister, Elizabeth, and her son, Benjamin, his own recently widowed mother, and his other sister, Mary, who was sickly for the whole of her life.

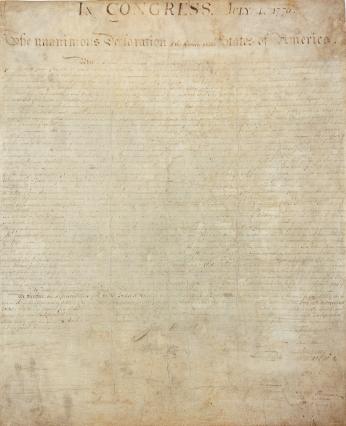

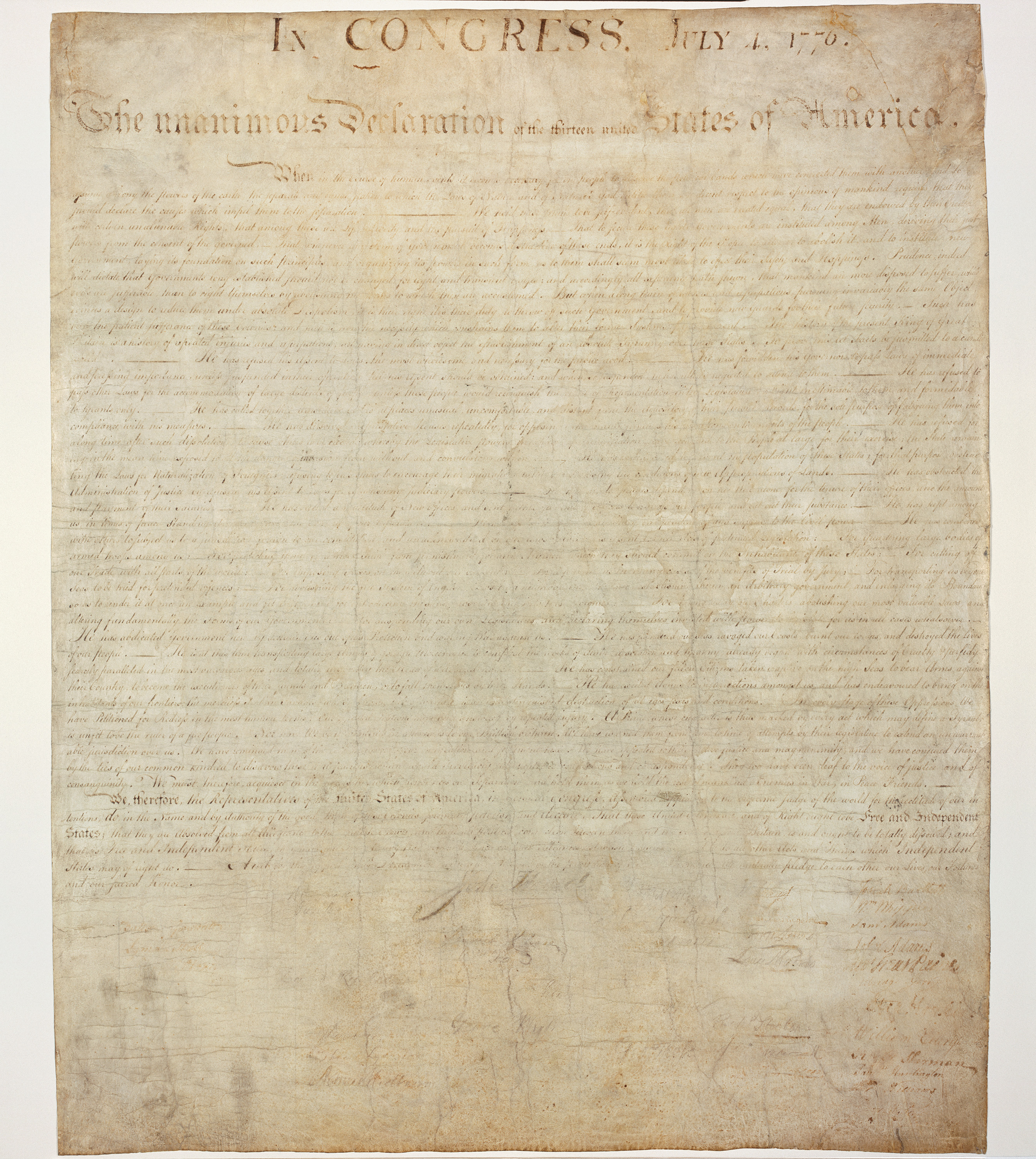

In 1797, the same year John Adams was elected president, Josias – who, like Adams, was a Federalist – became an engrossing clerk for the House of Representatives. Engrossing clerks, like those today, verified and maintained all of the documents of Congress.[1] He made a salary of $1000 dollars per annum, which is equivalent to between $18,000 and $20,000 today.[2]

As the government slowly relocated from Philadelphia to Washington D.C., there was discussion – led by then-Vice President Thomas Jefferson – to create a library for Congress.[3] In 1800, John Adams approved legislation granting money to establish the Library of Congress and acquire volumes from London.[4]

In 1801, once the books arrived and were stored in the U.S. Capitol building, and after Thomas Jefferson was elected the third president of the United States, Josias King saw an opportunity for a career change. A position had been created for the Librarian of Congress – the first in fact – and Josias wrote to the new president in January of 1802 applying for the position. In advertising his skills, King wrote that he was “principal clerk in the office, and the entire charge of the books attached to said office.”[5] He was given sanction by his new boss, John Beckley, that if selected for the position he could “discharge the duties of both offices.”[6]

However, as fate would have it, it wasn’t King who was appointed to head the new Library. Instead, it was Beckley himself – who happened to be a longtime friend of Jefferson and, like the President, a Democratic-Republican. Whether Beckley knew that he was to have the position when he allowed King to apply, we do not know. Nor do records allow us into the thoughts and feelings of King when he found out, but no doubt he was aware that his party affiliation was a factor in the decision.

Indeed, even in early America, political appointments were a ruthless business, as Beckley himself could attest. In 1789, Beckley had become the first clerk of the United States House of Representatives. In 1796, he campaigned for and managed Jefferson’s first election attempt. As we know, it was Adams who won after a race filled with bitter mudslinging. This meant that the Federalists were in power and the Democratic-Republicans were out – literally. Beckley was fired. However, his luck turned when Jefferson won in 1801. Jefferson gave Beckley his old job back, and as an additional thank you, made Beckley the first Librarian of Congress.[7]

Perhaps it turned out to be a bigger job than anticipated because Beckley – who had earlier suggested that if King were selected as the Librarian, he could handle both the Librarian duties and his normal clerk duties – soon turned to King for help with the Library. They reached an agreement whereby King would be the unofficial assistant librarian and Beckley would give King half of his Librarian’s salary.

All seemed well for several years, and then at the end of 1805, Beckley fired King. The reasons became clear in February of the following year when Josias presented a memorial to Congress expressing unjust treatment by Beckley. Josias articulated his complaint as follows (choosing to use third person voice to describe his plight as “the memorialist”):

“[I] your memorialist was appointed assistant librarian to label, arrange, and take charge of the books of the said Library; that the memorialist accordingly performed the said duty, and also executed the trust reposed in him as a clerk in the office of the Clerk to the House at the same time. That the present Clerk of your honourable body, who was appointed Librarian by the President of the United States [John Beckley], agreed to divide equally the compensation with your memorialist allowed by the said act, during the time he continued to serve in the Library. But the memorialist has not hitherto received the said compensation, as he had a right to expect, although repeated applications have in vain been made therefor, from the year 1802 to the present time.”[8]

Essentially, after taking a job that Josias King wanted, John Beckley asked for and received King’s help and never paid him. According to King’s own words, he and Beckley had multiple disputes over the matter, which Beckley solved by firing King. It is clearly this added insult, punctuated by the repeated abuses, which led King to approach Congress. The matter was investigated, but no action was taken. Was this another case of bias? The election of 1800 had produced a Congress where both houses were controlled by the Democratic-Republicans.[9]

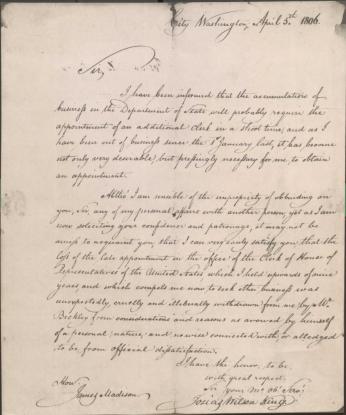

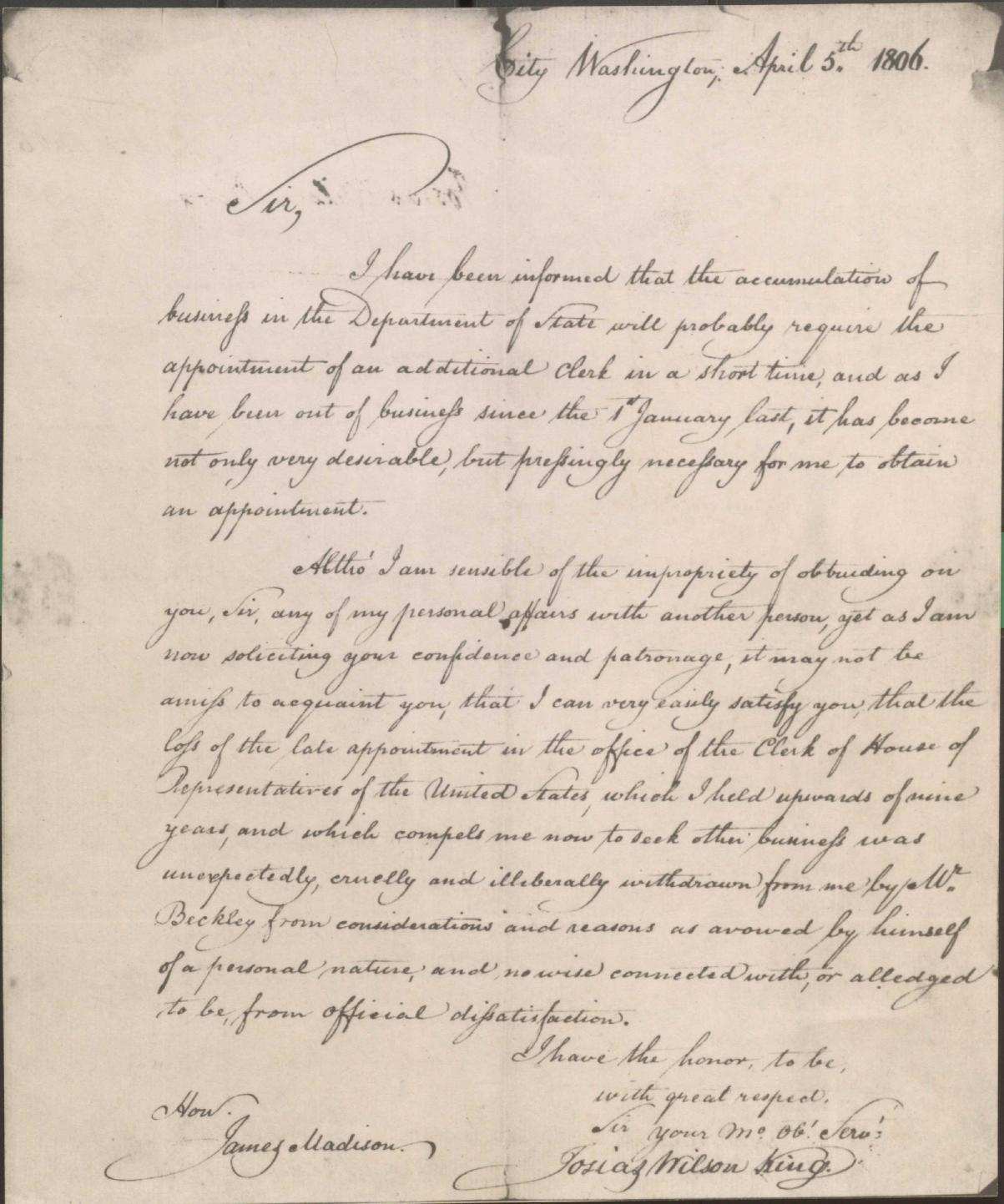

In 1806, King appealed to Secretary of State, James Madison, for a clerk positon in the Department of the State. In his application, King wrote about how his previous positon was “unexpectedly, cruelly and illiberally withdrawn . . . by Mr. Beckley” for personal reasons – which were acknowledged by Beckley himself.[10] King got the position. Beckley remained as the acting Librarian until his death in 1807, after which Josias Wilson King wrote again to Jefferson applying for the position. For a second time he was denied, and the position went to Patrick Magruder – another Democratic-Republican.

Josias Wilson King disappeared from the records until the War of 1812. In the summer of 1814 (yes, it’s still the same war), British troops had control of the Chesapeake and were marching towards Washington. It came as a shock to many, who anticipated that they would head to Baltimore, a prominent port city. The city was manic as citizens and government officials tried to pack up and leave in a hurry.

Amidst the chaos was Josias King, now clerk of the State Department. He with fellow clerks, Stephen Pleasonton and John Graham, began to gather up government archives, including the precious Charters of Freedom – The Declaration of Independence, the Constitution, and the Bill of Rights. They made bags to hold the records and tried to impound carts to haul the records. After all of their valiant effort, they managed to remove much of the archives from the city.[11] Contrary, many volumes from the Library of Congress were lost when the British set fire to the public buildings in the city. Perhaps if King had been acting Librarian instead of Magruder, they would have been saved.[12]

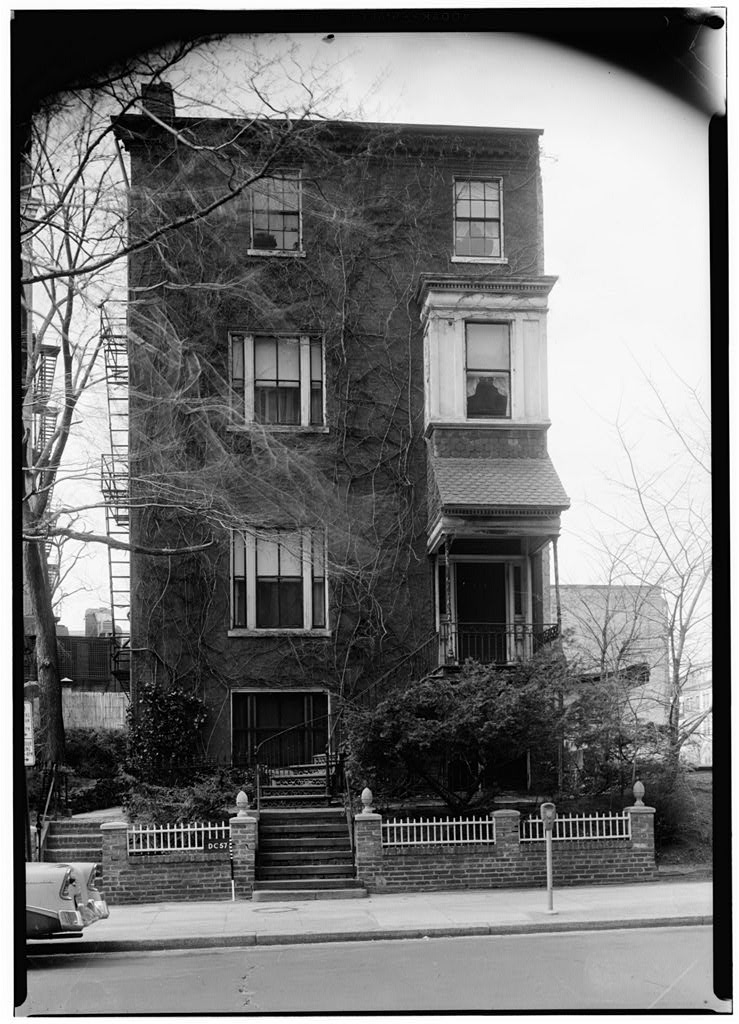

Aside from his involvement in two very prominent events, historical records have not been kind to Josias Wilson King. However, what is known is that he had a house built in Washington D.C., next to where the Corcoran School of Art & Design is now, and adjacent to the south lawn of the White House. It was on these very lawns that Josias’ daughter and only child, Mary Frances King, frequently strolled with Dolly Madison.[13] Josias resided here until his death in 1833. His home was torn down in the 1960s, marking with a very corporeal display that King had truly faded from collective memory.

Footnotes

- ^ “Engrossing and Enrolling Staff,” Office of the Secretary of the State, last modified 2014, http://secretary.senate.ca.gov/officeofthesecretaryofthesenate.

- ^ “U.S. Inflation Calculator,” last modified 2017, http://www.in2013dollars.com/1797-dollars-in-2017?amount=1000.

- ^ In the early years of the United States, it was common practice for the person who came in second place in the election to become Vice President. This often meant that the Executive branch was divided on issues. Imagine if that practice was the case today.

- ^ “Jefferson’s Legacy: A Brief History of the Library of Congress,” The Library of Congress, 1800-1992, last modified on March 30, 2006, https://www.loc.gov/loc/legacy/loc.html.

- ^ “To Thomas Jefferson from Josias Wilson King, 21 January 1802,” Founders Online, National Archives, last modified December 28, 2016, http://founders.archives.gov/documents/Jefferson/01-36-02-0257. [Original source: The Papers of Thomas Jefferson, vol. 36, 1 December 1801–3 March 1802, ed. Barbara B. Oberg. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2009, pp. 403–404.]

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ “A Guide to the John J. Beckley Papers: 1773-1807,” Virginia Historical Society, last modified June 20, 2003, http://www.vahistorical.org/collections-and-resources/how-we-can-help-y….

- ^ William Dawson Johnson, History of the Library of Congress: Volume 1, 1800-1864, (U.S. Government Printing Office, 1904), 35, as cited in Library of Congress Accession Book, 1800-1802, Library of Congress, MSS.ac: 484.

- ^ “The Election of 1800,” U.S. History: Pre Columbian to the New Millennium, last modified 2016, http://www.ushistory.org/us/20a.asp.

- ^ “To James Madison from Josias Wilson King, 5 April 1806,” Founders Online, National Archives, last modified December 28, 2016, http://founders.archives.gov/documents/Madison/99-01-02-0277. [This is an Early Access document from The Papers of James Madison. It is not an authoritative final version.]

- ^ Jessie Kratz, “P.S. You Had Better Remove the Records: Early Federal Archives and the Burning of Washington during the War of 1812,” Prologue Magazine, National Archives (Summer 2014): 41-44, accessed February 2017, https://www.archives.gov/files/publications/prologue/2014/summer/1812.p….

- ^ Christian A. Nappo, Librarians of Congress, (Rowman & Littlefield, 2016), 17.

- ^ King House, 528 Seventeenth Street Northwest, Washington, District of Columbia, DC,” Library of Congress, accessed February 2017, https://www.loc.gov/resource/hhh.dc0316.photos.

![Sketch of the mythical fuan by Pearson Scott Foresman. [Source: Wikipedia]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2023-10/Goatman_Wikipedia_Faun_2_%28PSF%29.png?h=64a074ff&itok=C9Qh-PE1)