The Hurricane That Created the Ocean City We Know Today

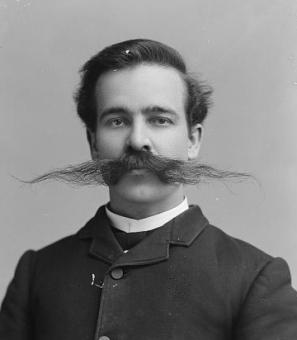

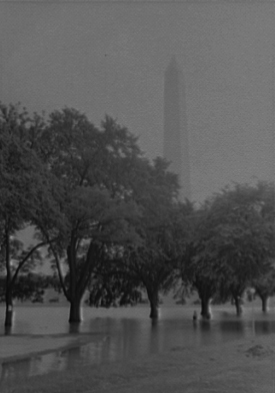

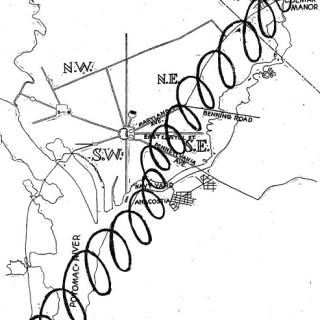

When readers of the Washington Evening Star opened their papers on August 25, 1933 they needed no reminder of what had just befallen the city. Two days earlier, the fiercest storm the nation’s capital had seen in decades pushed a wall of water up the Chesapeake Bay and Potomac River.

In a matter of hours, over six inches of rain fell on D.C. 51-mph winds toppled trees. Floodwaters submerged highways. Roofs were torn off buildings. A train crossing the Anacostia River was swept off its tracks, killing ten. The list went on…

Nevertheless, the Star’s editors sought to provide some perspective:

"There is nothing quite as effective as a raging storm shrinking the ego of man and making him aware of his own futility. Nature dished up only a few of her elements in the hurricane, and it was not a bad hurricane as hurricanes go. But in the course of a few hours the work of man for years and even generations was undone on some parts of the coast, and with splendid and awesome nonchalance the wind and the tides together changed familiar contours and made things over."[1]

Indeed, as rough as the storm had been on D.C., it was even more destructive in the beach communities to the east. At Public Landing, a resort community about 16 miles from Ocean City, Maryland, “virtually every cottage was swept away,” and felled telephone poles floated in the surf.[2] In Ocean City itself, the boardwalk began to break up and wash into town as buildings flooded. With communication lines down, frightened tourists and residents struggled to reach loved ones.

To add further danger, water was rising – fast. Ocean City had been inundated with rain for several days leading up to the big storm, which meant that the bays to the west of town were on the verge of overflowing. They did just that when the main event storm arrived on August 23. At the southern end of town near 1st Street, bay waters breached the barrier island and rushed into the sea.

Former Ocean City Roland “Fish” Powell, who witnessed the event as a 5-year-old, recalled the scene years later: “I was pretty young at the time, but I remember that storm and the Inlet being cut. We lived on Dorchester Street and Tom Cropper took his grandson and me and another boy and told us he was going to show us something we would probably never see again in our lives. Well, we went down there and saw water pouring across from the bay to the ocean.”[3]

As counterintuitive as it may seem, the breach, which washed out homes and businesses and caused hundreds of thousands of dollars in property loss, was actually a welcome development in the eyes of many locals.

In fact, businessmen in Ocean City had been pushing federal and state authorities to build an inlet, which would connect the ocean to the bay, for years. Such a waterway, they said, would be a game-changer for commercial fishermen. Without it, the only way to get fishing boats into the Atlantic was to launch from the beach, through the pounding surf. The process was incredibly difficult, requiring crews of men plus teams of horses or mules to pull boats across the sand. Unloading the day’s catch was similarly arduous.

Just a few months prior to the storm, Maryland Senator Millard E. Tydings and others had petitioned the Board of Engineers for Rivers and Harbors for funding to cut an inlet approximately 5 miles south of Ocean City. Tydings had argued that the project could attract big business to the area in the form of hundreds of fishing boats that could dock in the calm waters of the bay, and move easily between the ocean and markets in Baltimore, Washington, and Philadelphia.[4] Despite such appeals, the inlet project was not approved.

Clearly, however, Mother Nature had other ideas. And, once she cut the new inlet at 1st Street, Ocean City authorities were not about to let her good work go to waste. As the Star reported just two days after the storm:

“At Ocean City every visitor in recent years must have been told of the project some day to connect by a ship channel just south of the town the water of the Atlantic Ocean and Sinepuxent Bay. There was talk of obtaining money from the R.F.C. to do the necessary dredging. The storm came along and dredged a channel, wide and handsome, between the ocean and the bay. And now residents of the community are planning to seek governmental aid to erect bulwarks that will save the channel and keep it where it is.”[5]

Over the next two years, the state of Maryland and the federal government spent over $780,000 to stabilize the new inlet with jetties.[6] With easy access to the Atlantic, Ocean City saw a boom in sport fishing and tourism, which helped turn it into the vacation destination it is today.

A public works project courtesy of a hurricane? If only all storms came with silver linings.

See NOAA's rainfall map below:

Footnotes

- ^ “Merely a Reminder.” Evening Star, August 25, 1933. The storm that hit Washington had formed in the eastern Atlantic Ocean, south of Bermuda. It moved northwest, eventually achieving windspeeds consistent with a Category 4 hurricane before diminishing. It hit North Carolina on the morning of August 23 with winds of about 90mph and further weakened as it moved up through Virginia, D.C. and Maryland. As other articles in the Star and the Washington Post pointed out, the storm was no longer a hurricane by the time it reached Washington, but still packed a punch.

- ^ “Storm Subsides; 47 Known Dead.” Evening Star, August 25, 1933. p. A-3.

- ^ “80 Years Ago, Storm Created Ocean City Inlet.” Maryland Coast Dispatch, August 13, 2013.

- ^ “Summer Vacation: Greetings from Ocean City!” Underbelly Blog, Maryland Historical Society Library, June 27, 2013.

- ^ “Merely a Reminder.” Evening Star, August 25, 1933.

- ^ “Summer Vacation: Greetings from Ocean City!” Underbelly Blog, Maryland Historical Society Library, June 27, 2013.

![Sketch of the mythical fuan by Pearson Scott Foresman. [Source: Wikipedia]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2023-10/Goatman_Wikipedia_Faun_2_%28PSF%29.png?h=64a074ff&itok=C9Qh-PE1)