The Numbers Game at the National March for Lesbian and Gay Rights

When organizers from the National Gay Mobilizing Committee approached him in 1973 about a gay rights march in Washington, Larry Maccubbin was skeptical. A poor turnout, he feared, could undermine the hard work that he and other local activists had done to advance LGBT rights in the nation’s capital.

“We do not want to receive any setbacks at this time due to a poorly conceived, hastily planned, and shabbily supported demonstration,” he replied.[1]

Maccubbin was the founder and leader of the Washington Area Gay Community Council, which was “a coalition of organizations, clubs, services, and businesses that [served] gay DC.”[2] The council, founded in April 1973, functioned to help these organizations work together and better understand what the gay community wanted and needed.[3] WAGC even published its own local guide to the gay community called “Just Us” and, at the time when the march was first proposed, was attempting to build a gay community services center. In short, Washington’s gay and lesbian community had a lot to lose, which prompted Maccubbin’s response:

“I can safely say that, unless you can guarantee a minimum of 50,000 gays marching down Pennsylvania Avenue this spring, the march will be a political disaster. The numbers game is a political fact of life here. If less than 50,000 gays march, it won’t rate a two-inch write-up on the obituary pages, much less any serious consideration of the issues by the Congress. A small march will hurt, not help, the movement for justice and equality. A march of 50,000 gays, on the other hand, is not a very likely event in Washington. The largest gay marches to date drew less than 20,000 and that was in New York, where the vast majority of gays are privately employed and have little need to stay in the closet. There are about a quarter of a million gays in this area, but the majority… cannot or will not risk exposure at this time.”[4]

As Maccubbin alluded, for Washington’s gay and lesbian government workers, participating in such a march could mean coming out to their federal employers and losing their jobs. Federal employees had recently endured the “Lavender Scare,” where, while Senator Joseph McCarthy was trying to oust communists, the government was also trying to remove gays from their employment and the city. In 1947, the US Park Police began a “Sex Perversion Elimination Program” to target gay men, and a year later Congress passed an act "for the treatment of sexual psychopaths" in Washington.[5] Gay federal employees were targeted as a “security risk” in multiple cases, and an investigative subcommittee in Congress, the Hoey Committee, was formed to investigate and make a list of gay employees and the presumed dangers of employing them.[6]

These both paved the way for sexuality criteria to be included in Executive Order 10450, "Security Requirements for Government Employment,” which meant gays and lesbians could be easily banned from federal employment or from being consultants on government projects.[7] It’s estimated that between “5,000 and tens of thousands of gay workers lost their jobs” during the Lavender Scare, and that Maccubbin knew that the fear of unemployment would keep residents away from the march—and thus lessen its impact.[8]

As a result of such concerns, plans for the march, which was originally slated for the spring of 1974, progressed slowly, but national organizers continued to press the idea. As Gay Liberation Front founder Jeff Graubart explained, he wanted to bring together the gays across the country in “solidarity” and to “raise the national consciousness.”[9]

It took six years, three city-specific conferences (in Minneapolis, Philadelphia, and Houston), and various regional conferences, but Graubart and company finally set a date. The March would be held October 14, 1979. Many, including march coordinator Steve Ault, saw it as an extension of the Civil Rights movement, “Lesbians and gay men were there, hidden in that crowd that cheered Martin Luther King Jr.’s dream…Now, on October 14, 1979 lesbians and gay men, and our supporters will march for our own dream: the dream of justice, equality and freedom.”[10]

For this first march, organizers articulated five demands:

- Pass a comprehensive lesbian/gay rights bill in Congress

- Issue a presidential executive order banning discrimination based on sexual orientation in the Federal Government, the military, and federally-contracted private employment

- Repeal all anti-lesbian/gay laws

- End discrimination in lesbian mother and gay father custody cases

- Protect lesbian and gay youth from any laws which are used to discriminate against, oppress, and/or harass them in their homes, schools, jobs, and social environments.[11]

But, even as the march grew closer, Washington groups continued to question the march’s organization and timing. As Bob Davis, the former president of Washington’s Gay Activist Alliance, explained, “We were concerned that the march not interfere with a lot of the kinds of things we had done here. We have a pro-gay [city] administration and we didn't want to see ourselves straining our own resources for something that we didn't think there was a reason for.”[12] He continued, “It should have been a clue to a lot of the people that the national and local organizations did not give immediate endorsement.”[13]

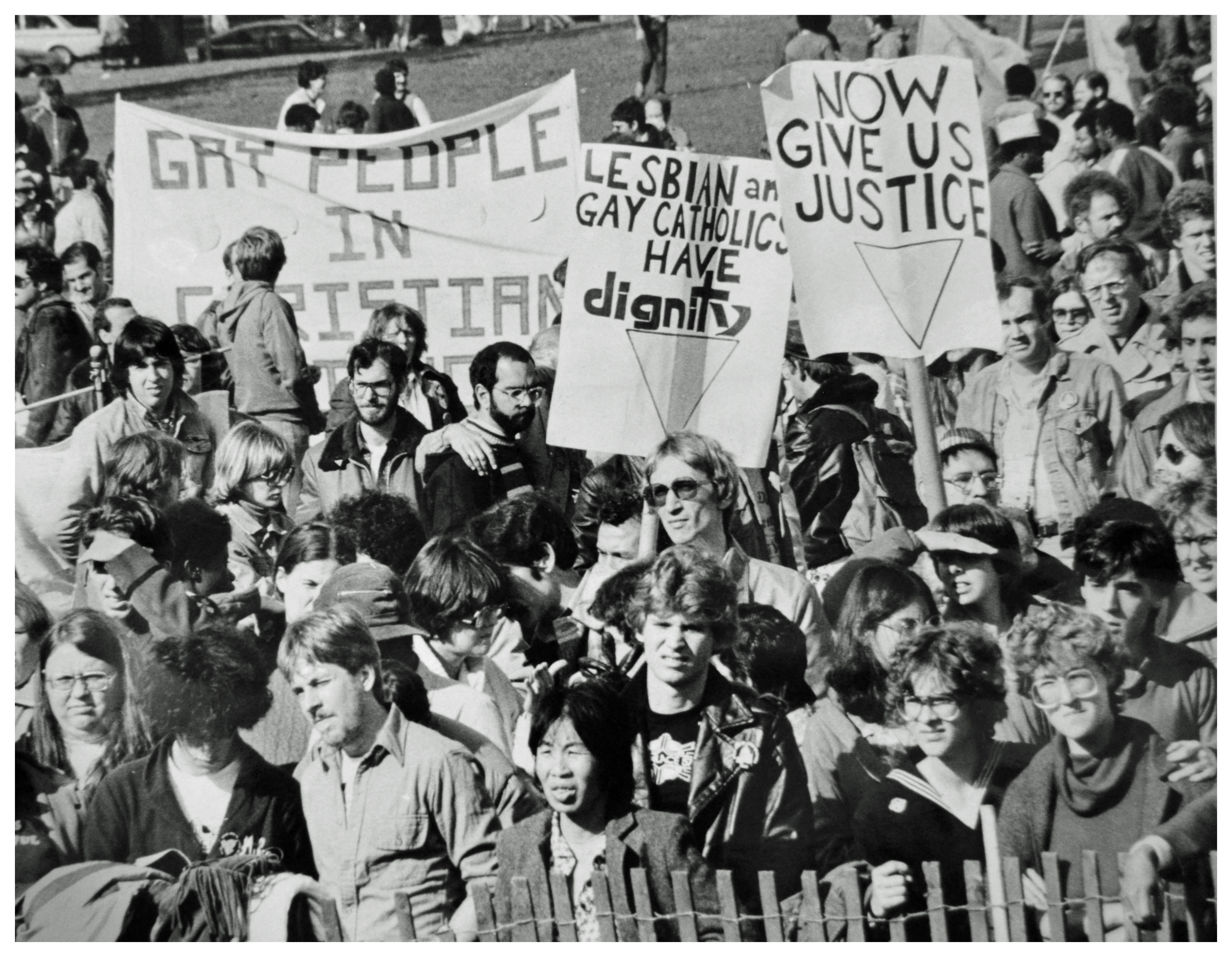

When the day finally arrived, the crisp fall weather chilled marchers who traveled to Washington from all over the country, New York to Alaska.[14] They made their way down Pennsylvania Avenue to the White House, though not without an accidental false start, where the march traveled fifty feet forward and then had to pause.[15] But once the march was really underway, the demonstrators moved along to proclaim “Gay love is good love,” and “The lord is my shepherd, and he knows I’m gay”[16] as they passed by the Capitol Building, the FBI, the Department of Justice, and the White House, where they had, just a few years earlier, been targeted for expulsion from the federal government during the “Lavender Scare.”[17]

In the immediate aftermath, there was considerable contention over the all-important numbers question. The Washington Post’s headline read “25,000 Attend Gay Rights Rally At the Monument,” later reporting in the story that that number came from a U.S. Park Police helicopter. Meanwhile, the Metropolitan Police reported the crowd at 75,000, and organizers claimed a quarter of a million people attended.[18] The New York Times used the 75,000 figure and included a quote from organizer Eric Rofes, which claimed “more than 100,000” participated.[19]

As Washington’s newspaper of record, The Post came under particular fire. The Blade, D.C.’s “Publication for the Gay Community,” quoted march leaders in calling the 25,000 figure as “absurd” and a “deliberate attempt to downplay the strength of the Gay Rights movement.”[20] (Interestingly, The Blade did not print particularly robust written coverage of the march, itself –just a short column amidst other short descriptions of other events related to the protest that weekend. It did, however, feature a two page spread of photos from the protest—including a photo of the crowd with the caption “Crowd estimates vary—here’s your chance for you to count for yourself!”[21])

Criticisms of The Post weren’t limited to the crowd size estimates. In one letter to the editor, William Burr Hunt II said, “You wrote only a brief article emphasizing the aspects that made it a ‘festive occasion,’ virtually ignoring the social and political significance, and including several references to the fundamentalist counter-demonstrators at the march and the prayer meeting on the Hill.”[22]

Brother Joseph Izzo, a minister who worked with an organization for lesbian and gay Catholics, similarly criticized The Post, saying “Your treatment does a great disservice to the cause of equality for the gay community and only served to foster the stereotypic, homophobic attitudes that so many people inflict on lesbians and gay men.”[23]

Despite the friction, the 1979 March did not kill the movement, as several local activists had feared beforehand. Another march would happen in 1987 to draw attention to the AIDS crisis, and the number of attendees would only grow with subsequent marches. Two hundred thousand people attended in 1987[24] and between 800,000 and 1 million in 1993.[25] Other demonstrations have followed as the movement for LGBTQ equality still continues today, growing more inclusive of other sexualities and identities.

Footnotes

- ^ David L. Aiken, “march : typescript of an article about the planning for an upcoming march on Washington for Lesbian and Gay rights,” Rainbow History Project Digital Collections, accessed May 9, 2017.

- ^ Washington Area Gay Community Council , “Just us : a directory of the Washington gay community,” Rainbow History Project Digital Collections, 1975, accessed May 11, 2017.

- ^ “The Washington Area Gay Community Council,” The Gay Blade, May 1973.

- ^ Ghaziani, The Dividends of Dissent: How Conflict and Culture Work in Lesbian and Gay Marches on Washington, pp. 46

- ^ Judith Adkins, “Congressional Investigations and the Lavender Scare,” Prologue Magazine (National Archives, 48:2, 2016), accessed May 11, 2017.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Ghaziani, The Dividends of Dissent: How Conflict and Culture Work in Lesbian and Gay Marches on Washington, pp. 44

- ^ D.C. Media Committee. “National March! On Washington for Lesbian and Gay Rights: Official Souvenir Program, pamphlet.” University of North Texas Libraries, Digital Library. (1979) Accessed May 9, 2017.

- ^ Thomas Morgan, “Gay Rights March on Mall Set Without Local Enthusiasm,” The Washington Post, Sept. 20, 1979.

- ^ Thomas Morgan, “National Gay Rights March, Counter Events Set Here,” The Washington Post, Oct 12, 1979.

- ^ “The March,” The Blade, (10:21), Oct. 25, 1979

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Courtland Milloy and Loretta Tofani, “25,000 Attend Gay Rights Rally At the Monument,” The Washington Post, Oct 15, 1979.

- ^ "The March," The Blade.

- ^ Milloy and Tofani, “25,000 Attend Gay Rights Rally At the Monument,”

- ^ Jo Thomas, “75,000 March in Capital in Drive To Support Homosexual Rights: 'Sharing' and 'Flaunting',” New York Times, Oct 15, 1979.

- ^ “How Many Were There?” The Blade, (10:21), Oct. 25, 1979.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ “Letters to the Editor: The Post’s Coverage of the Gay-Rights March,” The Washington Post, Oct. 23, 1979.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Lena Williams, “200,000 March in Capital to Seek Gay Rights and Money for AIDS,” The New York Times, Oct. 12, 1987.

- ^ Nadine Smith, “The 20th Anniversary of the LGBT March on Washington: How Far Have We Come?,” HuffPost, Apr. 25, 2013

![Sketch of the mythical fuan by Pearson Scott Foresman. [Source: Wikipedia]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2023-10/Goatman_Wikipedia_Faun_2_%28PSF%29.png?h=64a074ff&itok=C9Qh-PE1)