"Giving People the Courage to Be Themselves": Gay Pride Day in D.C.

Gay rights activist Larry “Deacon” Maccubbin was at a party with friends in 1975 when the topic of New York Pride eventually came up. As they were discussing who would be going, one of his friends asked why their own city, Washington, D.C., didn’t have a similar event ─ it was the nation’s capital, after all. The idea stuck in Maccubin’s head.[1]

In the mid 1970s, Washington, D.C. had a robust, albeit segregated, gay scene. Popular locales for Black gays included the Nob Hill Restaurant and social clubs like the Best of Washington.[2] White gays frequented places like the Georgetown Grill, the Lost and Found, and the DC Eagle. In prior years, there had not been many run-ins with the police, but suddenly officers began asking to see identification at the Georgetown Grill and harassing gay customers. Craig Howell, president of the Gay Activists’ Alliance from 1973-74 recounted, “One policeman had been coming in repeatedly asking for various licenses...about a week or so ago this took an ugly turn when the policeman brought in some of his buddies and did the usual harassment, and then afterwards they stayed outside the grill when it closed down and started harassing patrons by asking them for identification.” The police also raided the Cinema Follies movie theatre and the Club Bathhouse around that same time.[3]

Despite the occasional issues with law enforcement, gay and lesbian Washingtonians in the ’70s were making themselves more and more visible. In 1972, the Gay Liberation Front of D.C. had coordinated a Gay Pride Week under the leadership of Chuck Hall, Bruce Pennington, and Cade Ware.[4] The keynote event was a rally in Lafayette Park where about 50 men and women were “calling for more public displays of affection by homosexuals.” Even though Gay Pride Week was a one-time occurrence, Maccubbin’s event would turn into so much more.[5]

Shortly after that fateful party in early 1975, Maccubbin contacted his friend Bob Carpenter, a former president of the Gay Activists’ Alliance, to see if he wanted to coordinate a new gay pride event in D.C. Since he was out of a job at the time, Carpenter agreed to help, and the two got to work planning a block party that they decided to call “Gay Pride Day.”[6]

The logical spot for the event was in front of the Lambda Rising bookstore on 20th St., N.W., in the Dupont Circle neighborhood. It was the District’s first bookstore dedicated to selling gay and lesbian literature, and Macubbin was the owner. The date was set to June 22 ─ partly to commemorate the store’s first anniversary and also to accommodate D.C. gays who wanted to go to New York Pride later in the month. Before they could plan too much, however, the organizers needed the approval of over half of the business owners and residents on the block. Maccubbin and his partner Jim Bennett took around a petition, and every single owner and resident except for one signed without hesitation.[7] That was when they knew Gay Pride Day would be happening.

Several days before Gay Pride Day, Bruce Pennington went on the Friends Radio Program to discuss the upcoming celebration. When asked about why such an event was needed, Pennington responded, “I think it’s interesting that the last time there was a Gay Pride observance was in ’72 when it was a week of gay pride... and in the three years ensuing there’s been no gay pride observance, and now here in ’75 there’s a day. Over three years, it’s boiled down from a week to a day. In those three years, there’s been considerable achievements and contributions won by the gay community, particularly in the civil liberties and human rights area. The gay people who live in the District of Columbia now are assured the right to live under complete and full legal protection under the law, and that’s the main thing Gay Pride is going to celebrate.”[8]

When early afternoon on Saturday June 22 rolled around, Carpenter was worried. It was 1pm, which was when the party was supposed to start, yet only about 10 or 12 people were there in front of the bookstore. He expressed this concern to Maccubbin, who replied, “Don’t worry. They’re all on gay time. They’ll be here.” Sure enough, about an hour later there were almost 1,000 people in the street.[9]

An even balance of men and women showed up to Gay Pride Day, although unlike at Pride events today, they were dressed in simple, comfortable clothes. Most donned shorts with t-shirts or tank tops and were excited simply to be amongst others like them. Throughout the afternoon, they learned about gay organizations at the information booths participants set up, listened to live music from performers including lesbian singer Casse Culver, and enjoyed food and refreshments while socializing.[10]

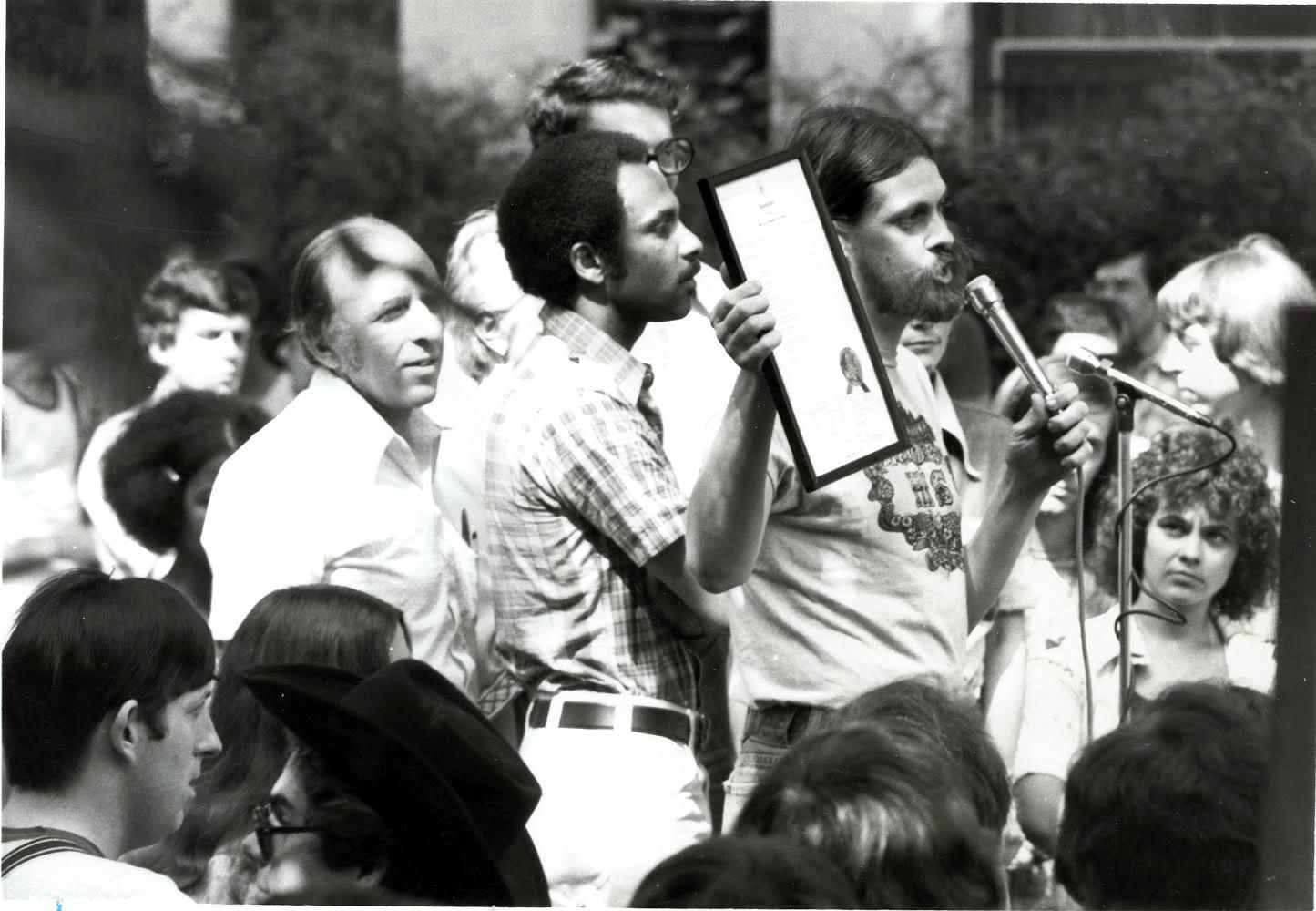

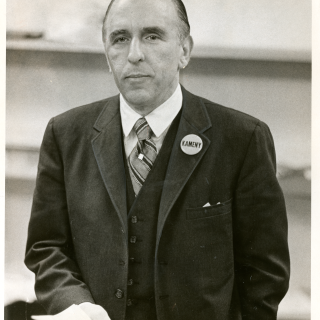

Standing next to Maccubbin and Frank Kameny, Ward 2 Councilman John Wilson, a strong advocate for gay rights, read an official proclamation from the D.C. City Council, which proclaimed June 22 as Gay Pride Day.[11] Neighbors including Louise Hamilton, who lived next door to Lambda Rising, watched the party from their homes. When reporters asked for her thoughts on the festivities, Hamilton exclaimed, “Lord, I’m loving it. It’s just wonderful. They’re having such a good time, and I’m so happy.”[12]

Attendees enjoyed all that the block party had to offer, but many still had to be careful. Despite Craig Howell’s claim that gay people had full legal protection in Washington, D.C., there were no laws at the time that prevented workplaces from firing employees based on sexual orientation, so plenty of people at Gay Pride Day were not publicly out. For the safety of closeted Pride goers, coordinators made sure the news media knew where they were allowed to take photos. They also let the crowd know to stand on a certain side of the street if they wished to be photographed or move to the other if they didn’t.[13]

D.C.’s first Gay Pride Day was one to remember, especially for Maccubbin. When reflecting on what it was like to see his vision become a reality, he said, “You get such a charge. It’s like going to an amusement park, like taking a rollercoaster ride. We got such a charge out of seeing so many people having such a wonderful time dancing in the streets, music going.” He also understood the significance of the event as the start of a yearly tradition. “People were just ecstatic. It was giving people courage to be themselves. Just to be themselves. That’s when we knew we had to do an annual thing. No question.”[14]

The following year when late June rolled around, Lambda Rising hired Frank Akers, a staff member of the Blade, to coordinate the second annual Gay Pride Day just three weeks before the party. Akers got in touch with Woman Sound for speakers and other sound equipment in addition to finalizing the other plans. On June 20, 1976, around 5,000 people showed up outside the bookstore, and once more, folks sipped on cold sodas and beer and danced to live music.[15] Attendees also partook in coin toss contests by the D.C.’s Gay Activists’ Alliance, bought balloons to support the Gay Men’s Counselling Collective, and contributed to other fundraisers held by the various organizations that had booths set up.[16]

However, not everyone was pleased to see the Gay Pride Day event return. When the D.C. Council declared June 20, 1976 as Gay Pride Day, John Wilson’s opponent in the Democratic primary election that year vehemently spoke out against Wilson’s support of the measure. Leroy Washington called Wilson “an embarrassment to the city for introducing a Council resolution allowing Gay Pride Day to fall on Father’s Day.” In response, Maccubbin announced to the attendees that the Council’s proclamation led one of Wilson’s supporters to withdraw their $3,000 contribution to his reelection campaign. To help him out, Maccubbin encouraged people to donate to the Councilman’s campaign right then and there as Kameny waded into the crowd to collect the money, which added up to $400.[17]

There were others who expressed their qualms with Gay Pride Day in print. In a column of the Washington Star, William Stahr of Baltimore argued, “It is contradictory because homosexuals feel self-disgust, not pride. It is self-defeating because it is an admission that homosexuals are not proud of themselves and must be prodded into a bolder stance….And it is outrageously anti-social because the encouragement of homosexuality weakens society by undermining the family.” Alongside Stahr’s opinion, however, the newspaper included Roy L. Sikes’, which simply stated, “June 20 has come and gone and the fathers of the city seem to be none the worse for it.”[18]

By the end of the afternoon, Akers reported to the Blade that he felt like that year’s Gay Pride Day “was a success spiritually, if not financially.” His efforts didn’t bring in enough money to offset the cost of putting the event together, but he and other organizers talked about having an even bigger block party the following year.[19]

Gay Pride Day did grow substantially over the next few years. It also underwent a change in leadership in 1980 when Maccubbin and Lambda Rising handed off the coordination of the event to P Street Festival, a nonprofit organization created that year. Under the leadership of Board Chairman Clint Hockenberry, the location was moved to Francis Park on 23rd Street and N Street, N.W., and the group added a parade the following year. The annual celebration continued to expand and in 1997, got a new name: Capital Pride. Now a month-long series of events, sponsored by the Capital Pride Alliance, Inc., it attracts hundreds of thousands of celebrants each year.[20] Quite an outcome for a dinner party conversation!

Footnotes

- ^ Jimmy Alexander, interview with Deacon Maccubbin and Jim Bennett, Out with Jimmy Alexander, podcast audio, June 30, 2020. https://www.owltail.com/podcast/UVQ5q-Out-with-Jimmy-Alexander/episodes.

- ^ Louis Berger, “Historic Context Statement for Washington’s LGBTQ Resources,” District of Columbia Office of Planning, September 2019, 60-63, https://planning.dc.gov/sites/default/files/dc/sites/op/publication/att….

- ^ “Craig Russell interview,” Rainbow History Project Digital Collections, accessed October 22, 2021, https://archives.rainbowhistory.org/items/show/272.

- ^ Rob Berger, “Remembering the modest origins of D.C. Pride,” Washington Blade, June 19, 2020, https://www.washingtonblade.com/2020/06/19/remembering-modest-origins-o….

- ^ Paul Hodge, “Open Display of Affection Asked by Gay Liberation,” Washington Post, May 6, 1972, B2.

- ^ Jonathan Padget, “A Brief History of (D.C.) Activism 30 Years of the GLAA,” Metro Weekly, April 12, 2001, http://www.glaa.org/archive/2001/mw30yearsofglaa0412.shtml.

- ^ Jimmy Alexander, interview with Deacon Maccubbin and Jim Bennett.

- ^ “Gay activism,” Rainbow History Project Digital Collections, accessed October 22, 2021, https://archives.rainbowhistory.org/items/show/228.

- ^ Jimmy Alexander, interview with Deacon Maccubbin and Jim Bennett.

- ^ “D.C. Celebrates Gay Pride Day ’75,” Gay Blade, July 1975, 1.

- ^ “June 22 In Washington, D.C. is: Gay Pride Day.”

- ^ Jimmy Alexander, interview with Deacon Maccubbin and Jim Bennett.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ “Gay Pride ’76 Brings Big Turnout” Gay Blade, July 1976, 1-2.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ “‘Gay Pride Day’ (4 Views),” Washington Star, June 27, 1976, 22.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ “History,” Capital Pride, accessed October 19, 2021, http://www1.capitalpride.org/about-us/history.

![Sketch of the mythical fuan by Pearson Scott Foresman. [Source: Wikipedia]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2023-10/Goatman_Wikipedia_Faun_2_%28PSF%29.png?h=64a074ff&itok=C9Qh-PE1)