They Paved Paradise and Put Up a Park and Shop

“Immaculate” and “modern to the nth degree” read a Washington Post ad one December day in 1930.[1] Sounds intriguing, but what dazzling, new technology was it describing? A television set? One of those new electric razors? Penicillin?

The answer: a strip mall.

Yes, today the opening of a strip mall is unlikely to drum up the same kind of enthusiasm that it did in 1930 (unless you’re particularly fond of IHOP or Bass Pro Shops), but nearly ninety years ago this present-day epicenter of suburbia was a brand-new concept in America and unheard of on the East Coast. That is, of course, until the opening of the “Park and Shop” in Cleveland Park.[2]

In 1930, cars were all the rage, and, for a modern shopper, they were a necessity. Consumers could arrive at a store in minutes, get what they needed, and drive back home without the burden of having to carry what they bought. The Cleveland Park neighborhood recently began commercializing and, given its easily accessible location, it was a popular place to shop.[3]

If you left your car on the street, you would be adding to the growing issue of traffic congestion. You could leave the car at home and walk, but having to clear busy streets like Connecticut Avenue was extremely dangerous before pedestrian crossing signals. On a business trip to L.A. in 1928, an official from the D.C. based real estate company Shannon & Luchs saw a solution to this problem in a new type of shopping complex called a “Drive-In.”[4]

The idea was very simple; instead of parking on the road, a car could pull off the street and “drive in” to a space adjacent to the store. After shopping, an attendant would help place the purchases in the car, and the consumer would drive off hassle-free.[5] Sound familiar? It should — it was a parking lot.

Shannon & Luchs thought D.C. would be a great place to capitalize on the idea of the Drive-In and, after a thoughtful study of which areas had the highest traffic density, decided to build the structure along Connecticut Avenue in Cleveland Park.[1] Designed with the help of architect Arthur B. Heaton, the P&S would feature stores intended to complement each other, providing customers a place for one-stop shopping.[6][3] You could buy a loaf of bread from Barker Bakery, eggs from the Piggly Wiggly, and reward your efficient shopping with confections from the Dutch chocolate store. The eye-catching, L-Shaped configuration of the stores was itself an advertisement for the P&S, attractive to someone driving by.[4]

Again, the architectural design and lure of one-stop shopping now seems far from revolutionary; the L-Shape is standard of most shopping centers, and one-stop shopping is the primary way people run errands. However, the features of this “new, modern merchandising development”[7] which we now take for granted excited Washingtonians in 1930. One Washington Post article marveled at the parking spaces, “freshly marked in gleaming white lines,” as well as the stores’ glass fronts, which allowed a patron “full view” of his car while he shopped.[1]

Praise for the innovation of the P&S didn’t stop there. The development gained a national reputation within months of its opening when it was featured in an Architectural Record magazine article on new tendencies in store design — the only building from the U.S. to be featured in the article. In 1932, the magazine featured the P&S again as a shining example of “a logical alternative” to shopping on traffic-heavy “Main Street.”[8]

Initially, the Park and Shop was meant to be a prototype for a dozen more that would soon be built around the D.C. area (and eventually, other cities). However, the looming Depression made developers wary of opening these new establishments. Ironically, the Great Depression actually helped the Cleveland Park institution. The New Deal called for an increased federal workforce, which, in turn, created a larger middle-class in D.C. More residents meant more residential construction, so a neighborhood institution like the P&S was able to get more visitors.[9]

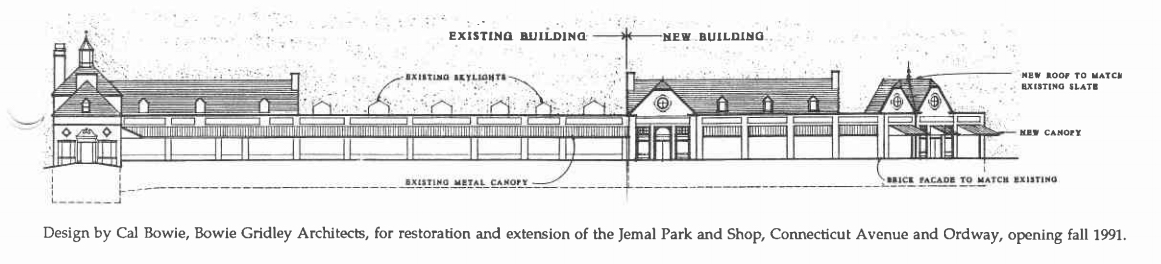

But the monopoly on one-stop, parking-accessible shopping didn’t last for long. Shopping malls, both urban and suburban, began to crop up in the years following World War II and posed stiff competition for the Park and Shop. The P&S struggled to survive into the ‘70s, and in 1988, developers from the Urban Group put forth a proposal to tear down the P&S and put in a larger structure with more shops, hundreds of underground parking spots, and space for housing and offices.[10] The end was near.

But, as the song goes, “You don’t know what you’ve got till it’s gone.” And the threat of demolition galvanized Cleveland Park residents to try and save the P&S.[10] They believed the Park and Shop was inextricably tied to the character of Cleveland Park, a relic of the neighborhood’s history. And so, they nominated Cleveland Park to the National Register of Historic Places as a neighborhood of distinct historical significance. What that meant was that any building in Cleveland Park constructed between 1880–1941 would have the full protection of D.C.'s historic preservation ordinance and be a "contributing resource" to the Cleveland Park historic district as a whole. In short, the Park and Shop could not be demolished.[11][12]

So now, nearly ninety years and over 65,000 strip malls later, what has kept the P&S alive is not that it is unique but that it is original.[13]However, many fail to recognize the P&S’ historical significance, since, at first glance, it doesn’t look much different than any other shopping center. But the unenthused reaction to the structure's mundane appearance only proves the P&S’ profound impact in shaping the modern American shopping experience. It was the model for the type of shopping-center that is still the standard today.

According to Carin Ruff, Executive Director of the Cleveland Park Historical Society, the best way to have the P&S thrive in years to come is by better communicating its historical value. One way to achieve this is through “adaptive reuse,” a method of modernization that would allow the P&S to keep its frontage (as is required of a contributing resource building) while repurposing some of the other space on the property.[14] Perhaps a patio partially extending into the parking lot, she suggests, so visitors could get up close to the structure and see the stone walls, the copper-covered cupolas, and other intricacies of the historic site.[12]

Adding a hang-out space in between a strip mall and a parking lot would certainly be unusual, but then again, so was the Park and Shop.

Footnotes

- a, b, c "New Stores Opened Unique in Capital," The Washington Post (Washington, DC), December 7, 1930, R2, https://search-proquest-com.library.access.arlingtonva.us/docview/15001….

- ^ It should be noted that the term “Strip-Mall” to describe the Park and Shop is somewhat anachronistic; the term did not come into existence until 1977. Cleveland Park residents still debate whether the Park and Shop can be classified as a Strip Mall or a shopping center.

- a, b Cherrie Anderson and Kathleen Sinclair Wood, Cleveland Park: A Guide to Architectural Styles & Building Types, illus. John Wiebenson (Washington, DC: The Cleveland Park Historical Society, 1998), 20.

- a, b Richard W. Longstreth, The Drive-In, the Supermarket, and the Transformation of Commercial Space in Los Angeles, 1914–1941 (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1999), 148.

- ^ Matt Novak, "This Automated Drive-In Market Was Pretty Retro, Even For 1956," Paelofuture, last modified October 1, 2013, accessed July 14, 2017, https://paleofuture.gizmodo.com/this-automated-drive-in-market-was-pret….

- ^ Paul Kelsey Williams and Kelton C. Higgins, Images of America: Cleveland Park (Great Britain: Arcadia Publishing, 2003), 110.

- ^ "You are Invited!," The Evening Star (Washington, DC), December 5, 1930, http://infoweb.newsbank.com.dclibrary.idm.oclc.org/resources/doc/nb/ima….

- ^ Longstreth, The Drive-In, 151.

- ^ Longstreth, The Drive-In, 158.

- a, b Williams and Higgins, Images of America, 111.

- ^ Carin Ruff, "What is the Period of Significance and what does it mean for Cleveland Park?," Cleveland Park Historical Society, accessed July 14, 2017, http://www.clevelandparkhistoricalsociety.org/cp-history/what-is-the-pe….

- a, b Carin Ruff, interview by the author, Sam's Park and Shop, Cleveland Park, DC, July 7, 2017.

- ^ Andrew E. Kramer, "Malls Blossom in Russia, With a Middle Class," The New York Times (New York, NY), January 1, 2013, accessed July 14, 2017, http://www.nytimes.com/2013/01/02/business/global/with-a-mall-boom-in-r…;

- ^ It should also be noted that the 1991 addition to the P&S does not have to remain intact because it was built after 1941 and is not a contributing resource.

![Sketch of the mythical fuan by Pearson Scott Foresman. [Source: Wikipedia]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2023-10/Goatman_Wikipedia_Faun_2_%28PSF%29.png?h=64a074ff&itok=C9Qh-PE1)