Jackson City: Arlington's Monte Carlo

On Memorial Day 1904, a group of civilians led by Alexandria County Attorney General Crandal Mackey boarded a southbound train from their meeting point in Washington to present day Arlington.[1] As they rode over the old Long Bridge, Mackey distributed axes, guns, and hammers to the men who, only moments earlier, had been sworn in as official deputies.[2] For decades, seedy settlements rife with betting houses, bars, and boudoirs prospered in the shadow of the nation’s capital. Gamblers had long sought protection by backing the powers that be in the dominant Democratic Party but Mackey and his supporters were a part of a new movement that claimed to oppose corruption. Mackey’s posse disembarked at the unimaginatively named “South End of Long Bridge Station” and began what would be the first of many raids.[3] Haphazard in their approach, the gang swarmed well-known gambling houses and left smashed-up, burned-out shells in their wake.[4]

Although illicit establishments spanned the southern bank of the Potomac, Mackey’s initial raid focused on two spots in particular: Rosslyn and Jackson City. Of course, Rosslyn survives to this day (albeit with an improved reputation), but few have ever heard of the once infamous Jackson City or of the man who proved its undoing.

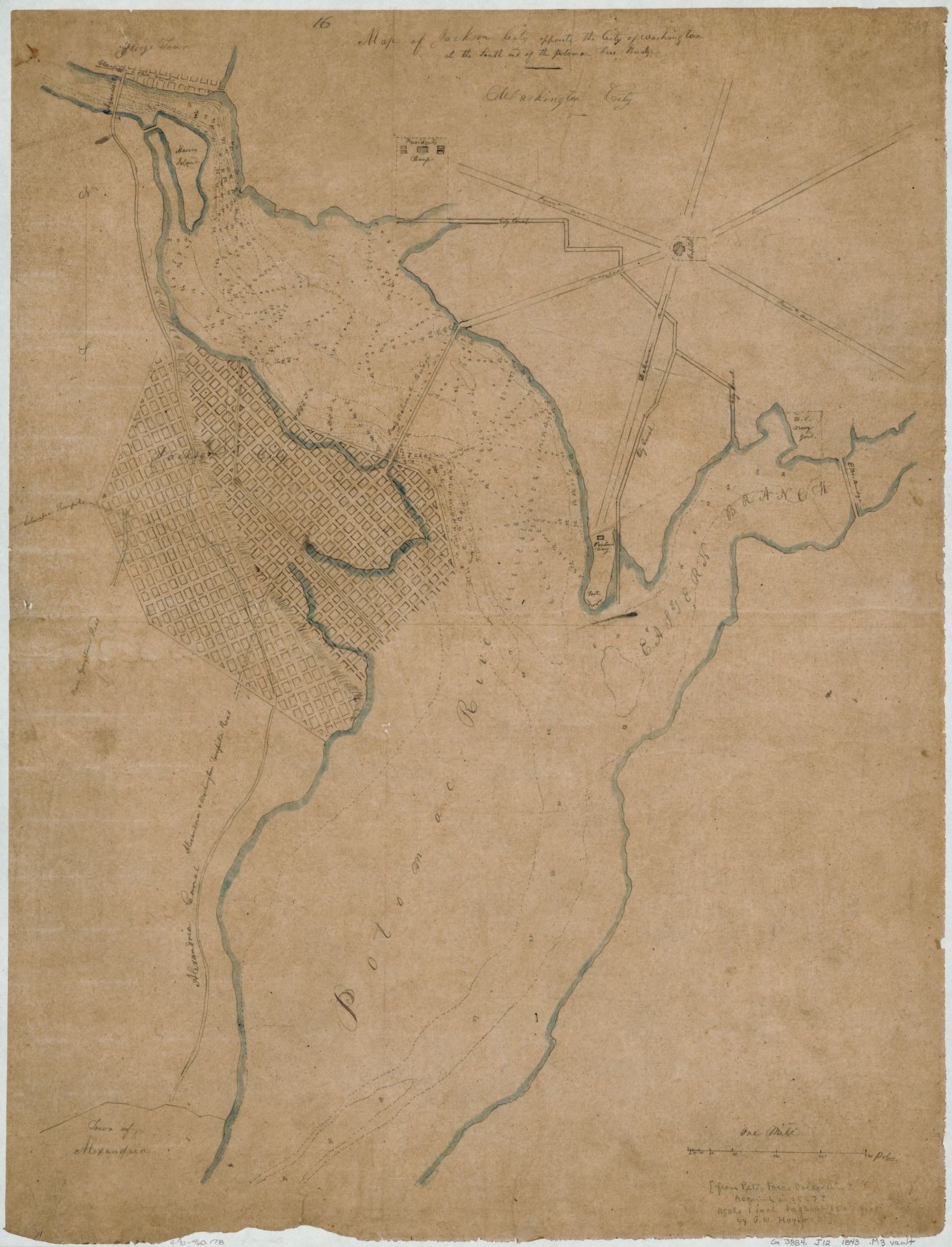

Though it was known as a sleazy outpost for the majority of its existence, Jackson City’s founders were motivated by a grand vision. In the early 1830s, a group of investors from New York believed that a city located near where the Pentagon and National Airport now stand would spur a cultural and industrial awakening in the District. Not only were the waters deep enough to dock seafaring ships but the area had easy access to Washington’s canals and the newly constructed Long Bridge. The investors believed that, if successful, this new city would transform the capital into one of the most prestigious cities in the world.[5]

Hoping for a blockbuster founding ceremony, the New Yorkers set out to secure the attendance of Washington’s biggest celebrity: President Andrew Jackson. Like all good lobbyists, the investors laid on the charm. They named the new city in Jackson’s honor and wrote him flattering letters:

“We are well aware that the enterprise as presented, does not exhibit a grandeur corresponding with the splendor of [your] name… [but we] feel sanguine that at no distant day JACKSON CITY will not be unworthy of its name. It has appeared to us also as peculiarly proper that the second man of the Union should have his name placed by the side of that of the first; we trust that, Jackson City will grow in happy union with Washington City…”[6]

A sucker for praise, Jackson “cheerfully” agreed to lead the cornerstone proceedings.[7]

On Jan. 11, 1836, anywhere from 7,000 to 10,000 Washingtonians braved frigid temperatures to watch the extravagant ceremony. Following a speech by George Washington Parke Custis, Jackson placed a cornerstone that was “large and elaborate, and had a foot-square hole in the top, into which were placed official documents, newspapers, coins, medals and other articles.” Although Jackson City would not live up to the image this extravagant cornerstone ceremony promise, the city would enjoy a second, more appropriate, “cornerstone ceremony” that same evening. In the cover of darkness, a group of spectators returned to the site, broke into the cornerstone’s capsule, and ran off with its contents.[8] No doubt, this moment of unscrupulous opportunism was a more fitting rite of initiation for the new city.

For the next several years, the “invisible city” was little more than a punchline. In 1843, reporting on a fire in Jackson City, The Whig Standard sarcastically wrote, “We regret to record the destruction of this ancient and populous city, (it contained one house)…requiescat in pace.”[9] In 1845, the New York Herald joked that President James Polk ought to fire Jackson City’s nonexistent Attorney General for “not doing justice to the bull-frogs and the mosquitos, the worthy inhabitants of the place.”[10] But gradually, a few buildings, including a tavern, went up and a settlement took hold.

Aside from a few informal prizefights at the local tavern, Jackson City got its first real taste of gambling following the Civil War; some gamblers from New Jersey moved to the marsh to escape anti-gambling laws in their home state.[11] However, gambling in Jackson City got its big break in the 1870s and 1880s when Congress began restricting gambling in the District. In response to the mounting restrictions, Washington’s gamblers abandoned their old headquarters on the corner of 7th St. and Florida Avenue NW and set up shop on the Virginia bank of the Potomac River.[12] The clampdown saw Jackson City transform from a place with a wagoner’s tavern, a few rum mills, and gambling shops into a booming shantytown.

By the late 1880s, thousands of gamblers streamed into the barebones resort each day, despite, or perhaps because of, its growing reputation as a hotbed of delinquency. Anyone interested in testing their luck knew where to go:

“There are no distinctions made on account of class or color, and the dapper government clerk has a good chance of brushing up against the boy who blackened his shoes earlier… the one is just as likely to make a winning as the other…”[13]

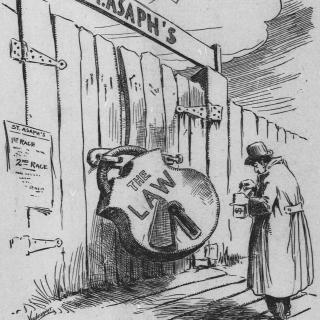

Be it cards, craps, or roulette, gamblers in Jackson City could win, or more likely lose, money in all manner of ways but Jackson City was perhaps most notable for its horse-racing pools. While Jackson City now had St. Asaph’s Racetrack to the south, gambling houses on the main drag had telegraph wires running to tracks across the country. According to reports, crowds would gather and watch the telegraph receiver click with the same excitement as those actually at a race.[14]

Even though Jackson City was a favorite destination for many Washingtonians, it became too much for the locals. In his book Shotgun Justice, journalist Michael Lee Pope describes the effects the area’s growing reputation had on crime:

“Northern Virginia was becoming the ‘Monte Carlo of the East,’ a reputation that attracted violent criminals from Washington and Maryland. Dangerous characters roamed the streets. Farmers returning home from the market traveled in packs to avoid being robbed by highwaymen…. ‘Killings were commonplace, and cases were never brought to trial,’" wrote Arlington historian Eleanor Lee Templeman.[15]

Officials in the District had long complained about Jackson City but, while most who frequented the town were Washingtonians, retrocession had put the land back in Virginian hands. In an 1890 interview in the Evening Star, Washington D.C.’s Detective Block complained that after dark “acts of rowdyism and lawlessness consumed the town” and called on Virginia’s Governor to put an end to the “disgusting display.”[16] On Feb. 25, 1892, Virginia’s Assembly passed State Senator’s Mushback’s bill banning all forms of gambling except horseracing (possibly due to the fact that Mushback was one of St. Asaph’s primary investors).[17] Nonetheless, the powers that be continued to enjoy the financial support of gamblers, and these laws went unenforced until Mackey stepped on the scene.[18]

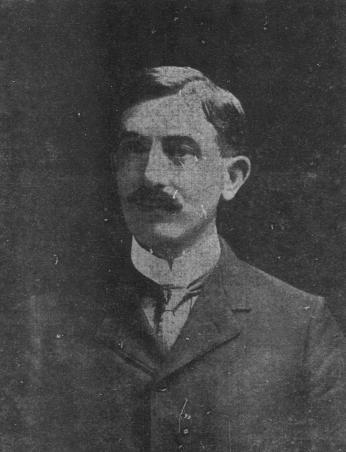

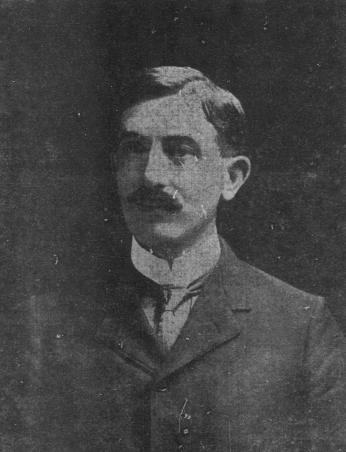

Crandal Mackey entered Virginia politics during a particularly tumultuous time. Though the Democrats had controlled Virginia since the end of the Civil War, numerous factions within the party were pushing back against Governor Thomas S. Martin’s “political machine.” In 1901, Crandal joined a faction known as the progressives. The progressives were an anti-corruption faction that primarily aimed to disenfranchise black voters who they believed sold votes and enabled corruption. They also took a hard stance against gamblers who were thought to support the “Martin machine.” The progressives swept to victory around the same time Mackey joined. In 1903, Crandal beat a number of other progressives in the race for Alexandria County Attorney General by instilling his image as the most ardent “anti-corruption” candidate.[19]

A tool of the new progressive machine, Crandal immediately set his sights on gambling in northern Virginia. While crime was certainly an issue in Jackson City and all along the Potomac, gambling interests opposed the progressive movement and there is little doubt Mackey aimed to consolidate the progressives’ hold over Alexandria County. Additionally, by this time the temperance movement, which overlapped with the progressives, was making a strong case for prohibition. Gambling and drunkenness were seen to go hand in hand; Jackson City was abound with both.

While Mackey’s Memorial Day raid on Jackson City and Rosslyn only yielded a measly six arrests, the action cemented Mackey’s legend.[20] His name was plastered the pages of local papers. Now, Mackey not only had the backing of Virginia’s progressive machine but he also had the fervent support of a public that had only just elected him by a minuscule two-vote margin. Emboldened, Mackey waged war with Jackson City, and the rest of “Monte Carlo.” Repeated raids combined with a 100% conviction rate ensured his victory over NoVa’s casino towns and three terms in office.[21]

Today, few reminders of this period in history remain. There is no trace of Jackson City. The Navy-Merchant Marine Memorial is rumored to have been built on top of Jackson’s cornerstone but other records suggest it was dragged to an unspecified location in Fairfax County. Rosslyn exists in name but its pristine towers and business centers make it a far cry from what the area once was. In 2014, a park named in Mackey’s honor was replaced by one of these new developments.[22]

Footnotes

- ^ George Kennedy, “Arlington Become Real Metropolis as Land Boom Sends Values Up 10-Fold,” Evening Star (Washington), Jan. 8, 1951, NewsBank.

- ^ Michael Lee Pope. Shotgun Justice: Once Prosecutor’s Crusade Against Crime and Corruption in Alexandria and Arlington (Charleston, SC: The History Press, 2012), 66.

- ^ Ibid., 43.

- ^ “The Result of a Raid,” Evening Star (Washington), May 31, 1904, NewsBank.

- ^ “Old Hickory Took Part,” The Washington Post (1877-1922), Jun. 29, 1890, ProQuest Historical Newspapers: The Washington Post.

- ^ “Jackson City,” The North Carolina Standard (Raleigh), Jan. 14, 1836, Library of Congress: Chronicling America.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ “Old Hickory Took Part.”

- ^ “Jackson City in Ashes,” The Whig Standard (Washington), Dec. 14,1843, Library of Congress: Chronicling America.

- ^ “Latest Intelligence by the Mail,” The New York Herald, Dec. 15, 1845, Library of Congress: Chronicling America.

- ^ Pope, Shotgun Justice, 43.

- ^ “War on Monte Carlo,” Evening Star (Washington), Jan. 23, 1892, NewsBank

- ^ “On the Cloth of the Green,” Evening Star (Washington), Jan. 30, 1892, NewsBank.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Pope, Shotgun Justice, 32.

- ^ ”Monte Carlo,” Evening Star (Washington), Dec. 16, 1891, NewsBank.

- ^ O'Bannon, J. H. Joint Resolutions Passed by the General Assembly of the State of Virginia During the Session of 1891-1892. Richmond. https://hdl.handle.net/2027/uc1.a0001738137.

- ^ Pope, Shotgun Justice, 32-33.

- ^ Ibid., 19-20, 32-37.

- ^ Ibid., 71.

- ^ Ibid., 103-105.

- ^ Michael Lee Pope, “Crandal Mackey Park Disappears,” The Arlington Connection, Jul. 30 - Aug. 5, 2014. 3.

![Sketch of the mythical fuan by Pearson Scott Foresman. [Source: Wikipedia]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2023-10/Goatman_Wikipedia_Faun_2_%28PSF%29.png?h=64a074ff&itok=C9Qh-PE1)