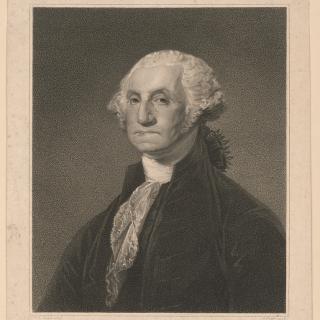

Matildaville: George Washington's Ghost Town

If you’ve ever hiked Great Falls Park, you might have stumbled across the ruins of a long lost town. Matildaville was to be a bustling hub on an expansive trans-national trade route. But today, a spattering of stone ruins and a handful of crumbling locks are all that remain of a town conceived by none other than George Washington.

Following the Revolutionary War, George Washington devised a canal system that would link the Potomac and Ohio rivers. Washington argued that by encouraging trade, his system would unite the thirteen States and the western frontier and also knew that his Western Pennsylvanian estate stood to soar in value were such a network established.[1] Driven by private and public gain, Washington lobbied Maryland and Virginia to support his plan. In November 1784, Maryland’s assembly approved a plan “establishing a company for opening and extending the navigation of the river Patowmack” and on December 13, 1784, Virginia concurred.[2] “The Patowmack Company” was formally established on May 17, 1785 and Washington was put at the helm.[3]

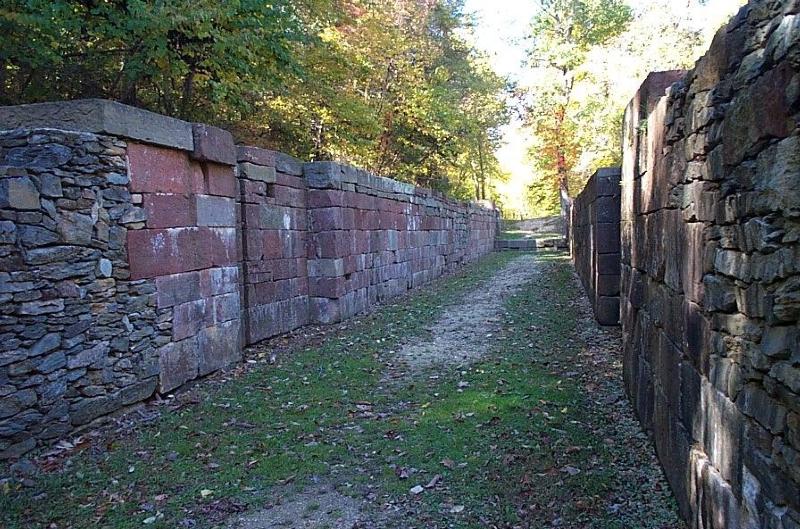

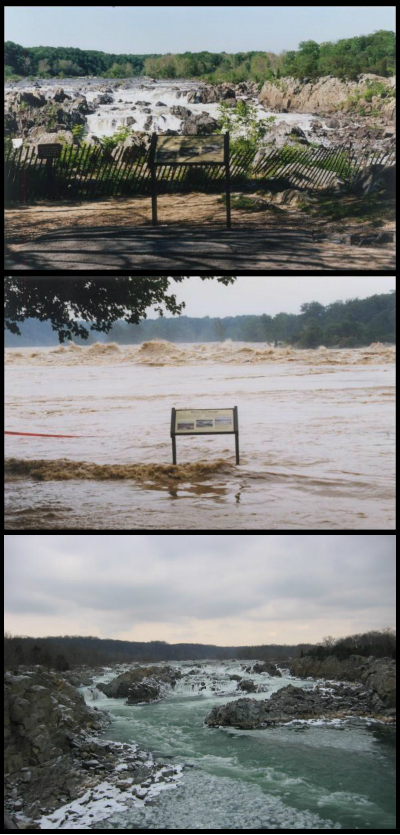

With their eyes on the prize, Washington and his partners vastly underestimated the task at hand. In addition to circumnavigating the Great Falls’ 80-foot drop, the Patowmack Company would have to skirt four smaller falls and deepen parts of the river before cargo-laden boats could safely navigate the waters.[4] Laborers, most of them indentured servants or slaves, worked on the Potomac canals for 17 years during which time Matildaville developed and transformed from an informal settlement to a chartered town.

Convinced by Washington’s vision of a town on the banks of the Great Falls basin, Virginia’s General Assembly issued a charter in December 1790.[5] Three years later, Henry Lee III, father of Robert E. Lee, took out an optimistic 900-year lease on the newly chartered land. Lee called the area “Matildaville” in honor of his late wife and second cousin Matilda Ludwell Lee.[6] While the Patowmack Company wouldn’t complete construction on the Potomac until February 1802, workers at Great Falls were moving boats and collecting tolls by February 1798.[7] By August 1800, the Great Falls basin was full of boats and Matildaville’s workforce moved cargo day and night.[8] The Patowmack Company had proven that they could safely and successfully skirt the most treacherous stretch of the Potomac River. The Great Falls canal system was dubbed the greatest American engineering feat of its time, and tourists visited Matildaville from far and wide to watch it in action.[9] Matildaville was bustling and before long it laid claim to a forge, sawmill, grist mill, store house, market house, public house, boarding house for workers, the Patowmack Company’s headquarters, and at least five private homes.[10] Buttressed by these initial successes, few in Matildaville would have predicted the tough times to come.

Matildaville’s existence was tethered to the success of the Patowmack Company and investors soon realized that the business was unsustainable. The state of the art canals had come at a cost. While the Patowmack Company collected $172,689.39 in tolls by 1818, it had spent over $650,000 on construction and could barely pay interest on its numerous loans.[11]

The company’s financial issues were compounded by the fact that “America’s greatest engineering feat” didn’t actually work all that well. In the summer, water levels dropped and the canals dried up, in the rainy months, downpours flooded the canals making passage too dangerous, and in the winter, the canals froze over.[12]

It became clear that Patowmack Company would not dig itself out of debt so in 1823, Virginia and Maryland passed concurrent legislation “providing for the surrender, at the proper time, of the charter of the Patowmack Company to the Chesapeake & Ohio Canal Company.”[13] The Patowmack Company ceased to exist on August 15, 1828 and its assets, including the Potomac Canals, were handed over to the Chesapeake & Ohio Canal Company.

Like the Patowmack Company, the C&O Company hoped to link the Atlantic Ocean and the Ohio River valley. However, the C&O had a more ambitious plan headed by superior engineers, and, whereas the Patowmack Company was only backed by Virginia and Maryland, the C&O Company had the support of Virginia, Maryland, Ohio, Pennsylvania, and the United States. The C&O made use of the Patowmack Company’s Canals for a little over a year before abandoning them in 1830, shifting operations to a newly cut Potomac canal on the Maryland side of the river which almost entirely avoided use of the Potomac River’s natural stream.[14] Now effectively bypassed, Matildaville’s workers left and the flow of tourists and traders slowed.

The collapse of the Patowmack Company could have been the end of Matildaville but the town was given a lease on life in the mid 1830s, when investors Thomas Jones, William Bradley and Hall Nielson moved in to capitalize on the town’s industrial remnants. They bought the land for $3,000 and established a water-powered textile factory, which they called the Great Falls Manufacturing Company.[15] On March 6, 1839, the Virginia Assembly passed legislation, which repealed Matildaville’s Charter and acknowledged the formation of a new town known as South Lowell.[16]

The Great Falls Manufacturing Company quickly grew into a publicly traded company employing over 200 hundred workers. The town benefited from the success of the company and by the 1850s, Virginia’s Assembly discussed funding a train line through South Lowell.[17] However, progress came to a screeching halt in 1858 when The United States Government slapped the Great Falls Manufacturing Company with a lawsuit. In 1853, the State of Maryland granted the U.S. Government the power to condemn land along the Potomac River and construct an Aqueduct. Being that Maryland’s claim to the Potomac River extends right up to the Virginian bank, the Federal government argued that it was entitled to condemn the Great Falls Manufacturing Company as the company’s mills made use of the Potomac’s currents. While Virginia came to the company’s defense, the 40 year legal battle ultimately spelled the end for South Lowell.[18]

One family remained after South Lowell’s collapse. The Dickey family predated Matildaville’s charter and had watched as two industrial towns rose and fell on the doorstep of their family home. For nearly 200 years, upwards of six generations of Dickeys occupied the same 18th century barn.[19] William “Billy” Dickey had once allowed the home to be used as an office for South Lowell’s Great Falls Manufacturing Company, but more famously operated the barn as a public house for visitors to the Great Falls. The Dickey’s were said to have played host to every president from George Washington to Teddy Roosevelt.[20] In 1935, the last of the Dickeys moved away and in June 1950, Dickey’s Farmhouse, Matildaville’s first and last building, went up in flames. The blaze was the final nail in the coffin of a town that was never meant to be.[21]

Footnotes

- ^ Ferling, John. The Ascent of George Washington: The Hidden Political Genius of an American Icon. New York: Bloomsbury, 2009. 250-252.

- ^ Maxcy, Virgil. The Laws of Maryland: 1692-1785. Maryland: P. H. Nicklin & Company, 1811. 488.; Journal of the House of Delegates of the Commonwealth of Virginia. Richmond: Commonwealth of Virginia, 1828. Internet Archives e-book. 68.

- ^ National Park Service. “The Patowmack Canal.” NPS.gov. https://www.nps.gov/grfa/learn/historyculture/canal.htm.; Journal of the House of Delegates of the Commonwealth of Virginia. 89.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Acts passed at a General Assembly of the Commonwealth of Virginia 1839. Richmond: Commonwealth of Virginia, 1839. HathiTrust e-book. 185. https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=njp.32101073363218;view=1up;seq=7.

- ^ Deed of Lease from Bryan Fairfax to Henry Lee, 1793. Fairfax County, Commonwealth of Virginia. Fairfax Deed Book Index, 152. Fairfax Circuit Court Historic Records Room, Fairfax County, Virginia.; National Park Service. “The Patowmack Canal.”

- ^ Bacon-Foster, Corra. "Early Chapters in the Development of the Potomac Route to the West." Records of the Columbia Historical Society, Washington, D.C. 15 (1912): 187-188, 194. http://www.jstor.org/stable/40067035.

- ^ Ibid., 191.

- ^ Ibid., 194.

- ^ Ibid., 178, 192.

- ^ Ibid., 276-277.

- ^ National Park Service. “The Patowmack Canal.”; “Washington’s Great Falls Canal,” Evening Star (Washington D.C.), Oct. 13, 1907. Library of Congress: Chronicling America.

- ^ Bacon-Foster, Corra. "Early Chapters in the Development of the Potomac Route to the West." 232-233.; “Chesapeake and Ohio Canal,” The Alexandria Gazette (Virginia), Nov. 11, 1823, NewsBank.

- ^ Ibid., 242-243.

- ^ “News of the Day,” The Alexandria Gazette (Virginia), Nov. 25, 1845, NewsBank.

- ^ Acts passed at a General Assembly of the Commonwealth of Virginia 1839. 184-185. “[Virginia; Lowell],” The Alexandria Gazette (Virginia), Sept. 23, 1847, NewsBank.; “Communications. The Great Falls Of The Potomac—‘South Lowell.’,” The Alexandria Gazette (Virginia), Sept. 25, 1847, NewsBank.

- ^ “The Experiment,” The Alexandria Gazette (Virginia), Feb. 28, 1834, NewsBank.; “The Great Falls Manufacturing Company,” The Alexandria Gazette (Virginia), Sep. 7, 1853, NewsBank.; “[Legislature; Measures; Regardless; Commonwealth; Application; Railroads]” Alexandria Gazette (Virginia), Feb. 26, 1856. NewsBank.

- ^ Patents on the Potomac: Court Cases & Documents Concerning Condemnation Proceedings for the Washington Aqueduct 2000. State of Maryland. Maryland State Archives. http://msa.maryland.gov/megafile/msa/speccol/sc5700/sc5796/000024/00000….

- ^ “Death of Capt. J.H. Dickey” Washington Post, 21 Oct., 1896. ProQuest Historical Newspapers: The Washington Post.

- ^ “Death of Capt. J.H. Dickey.”; “Trip to Great Falls: Out-of-the-way Spot Now Brought Within Reach,” The Washington Post (1877-1922), Jul. 14, 1901, ProQuest Historical Newspapers.; “The Potomac Canal,” Evening Star (Washington D.C.), May 13, 1893. Library of Congress: Chronicling America.; “Fire Damages Dickey House On Potomac: Family of Six Flees Historic Structure At Great Falls, Va.,” The Washington Post, 23 Jun., 1950: ProQuest Historical Newspapers.

- ^ “Fire Damages Dickey House On Potomac: Family of Six Flees Historic Structure At Great Falls, Va.”

![Sketch of the mythical fuan by Pearson Scott Foresman. [Source: Wikipedia]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2023-10/Goatman_Wikipedia_Faun_2_%28PSF%29.png?h=64a074ff&itok=C9Qh-PE1)