What is the True Story Behind Georgetown's Gun Barrel Fence?

At first sight, the old wrought iron fence on the corner of P and 28th streets appears indistinct from the many other railings that skirt Georgetown’s redbrick sidewalks. Upon closer inspection, however, it’s clear this fence is unique. Cracks in some of the pickets reveal that although each upright is hollow, the walls of the pickets are far thicker than is structurally necessary for a perimeter fence. Plus, a number of the pickets feature small nubs just below the attached spikes, which, even to the untrained eye, resemble gun sights. While the Gun Barrel Fence has long been a Georgetown landmark (and has even earned itself a coveted Google Maps marker), the fence’s origins remain shrouded in mystery and misconception. Let’s bust some myths, shall we?

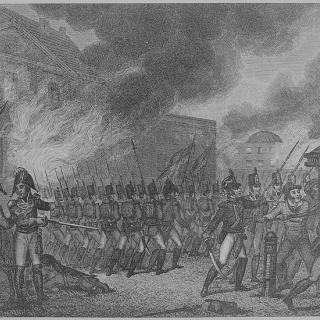

The most often-repeated story about the Gun Barrel Fence claims it was made of old rifles from the Revolutionary War. It’s said that as British troops began to encroach on Washington during the War of 1812, the War Department issued an urgent plea for financial support and Georgetown’s wealthy residents answered the call. They loaned their fledgling government vast sums of money full in the knowledge that repayment was dependent on a miraculous American victory. In spite of the devastating British invasion of Washington, the Americans emerged from the war victorious.

Once the smoke settled, the War Department decided to start repaying those who had backed the war effort but, like the rest of the federal government, was strapped for cash. So, rather than repay the debt in cash alone, the War Department summoned the patriotic creditors to Washington’s Navy Yard and allowed them to sift through a mountain of scrap metal and take whatever they wanted as partial repayment.

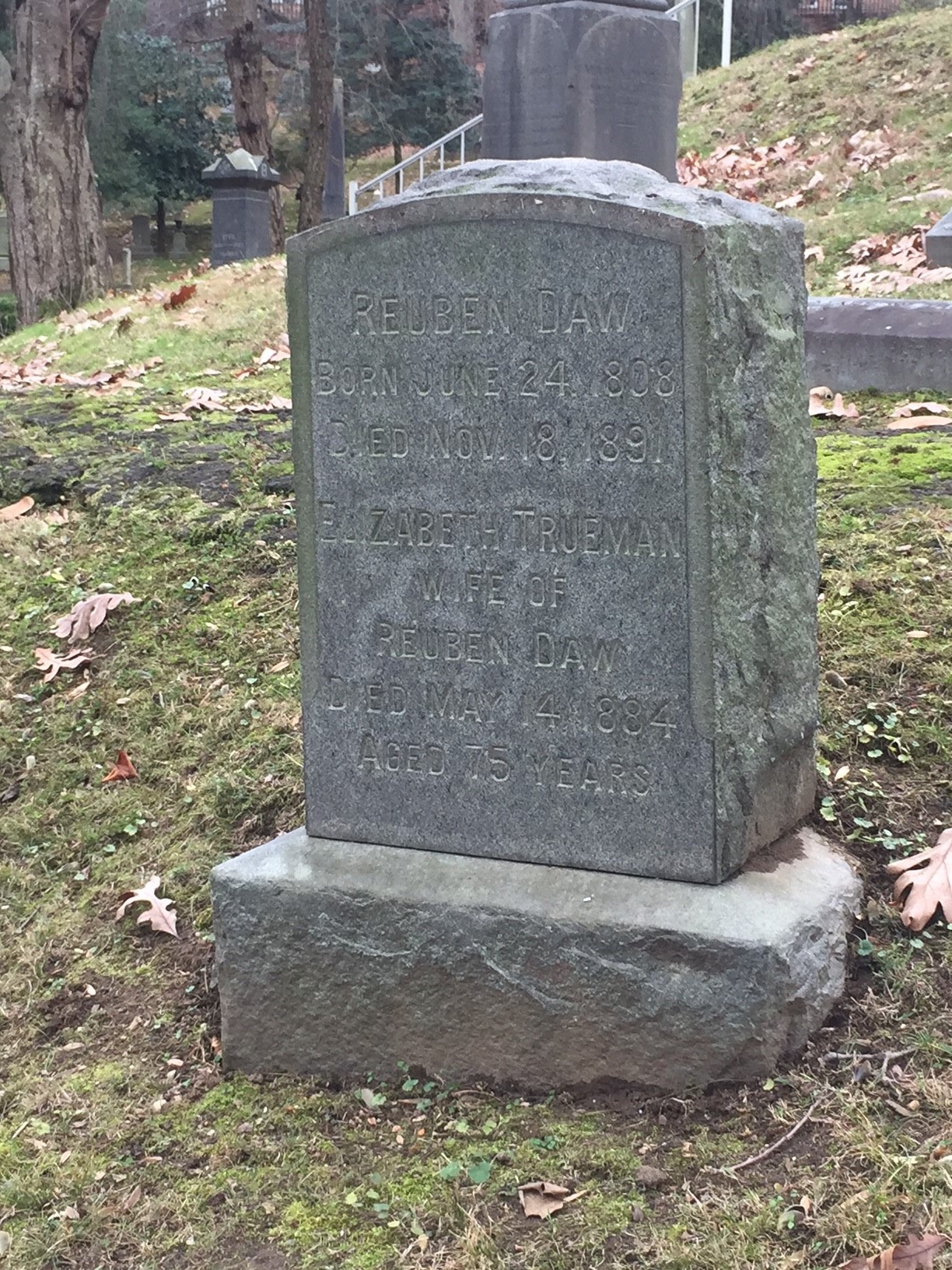

As the donors picked through the scrap, a man named Reuben Daw stumbled across a pile of rusted old flint lock muskets from the Revolutionary War. Daw gathered as many of the muskets as he could haul and went back home. It’s said that the Georgetowners who loaned the government money started to display their salvaged scraps outside their home as a symbol of their role during the war. Daw decided to do so by detaching the gun barrels from the stocks and using them to fence his four homes on P and 28th streets.

Stories along this line once have been reproduced a number of times over the past century. It first appeared in print in The Washington Herald on June 25, 1911 and a shortened version was published in Popular Mechanics five months later.[1] Variations continued to surface in a number of publications and have more recently popped up online.[2]

While the “Revolutionary Rifle Story” has lived a long life, it was not the only origin story for the Gun Barrell fence. Between September 1907 and August 1908, The Washington Bee, the Evening Star, and The Washington Times all printed versions of another story. These accounts – which seem to have been written by the same person – claimed that the Reuben Daw bought a load of old defective Hall M1819 breech-loading rifles from the Harpers Ferry armory during the 1860s.[3] Pretty straight-forward, and that’s where the Bee left it.

The Star and the Times, however, had much more to say. In their accounts, the authors write that while the dangerous Hall Rifles were being stored at Harpers Ferry, the armory was preparing to ship some of the rifles out west to San Francisco. Unbeknownst to the workers at the armory, the famed abolitionist John Brown and his militia had been watching the arsenal and planned to seize the shipment of firearms. On Oct. 16, 1859, the Brown militia marched into Harpers Ferry and took control of the armory gate. They established what was for two days known as “John Brown’s Fort.”

Anyone familiar with John Brown and his capture of the Armory will know that the insurrection did not end well for the abolitionists. After a bloody battle, the U.S. Marines recaptured the Amory, and Brown was hanged for treason. In the Star and Times accounts, the author claims that, for whatever reason, the raid prompted the military to cancel the shipment of Hall Rifles and to auction them off instead. As in the first version of the “Hall Rifle Story” printed in the Bee, Daw purchased the defective guns and built the fence.

But that’s not all. Taking it one step (actually several steps) further, the accounts in the Star and Times also inserted a supernatural twist:

“It is related that soon after the fence was built a young man declared that he had seen a soldier in continental uniform examine the gun barrels in the dead hours of night. As the young man was given to imbibing a little too freely at times the citizens refused to believe his story, going on the supposition that he was "seeing things." However, it was not long before substantial citizens likewise began to see through the same glasses as did the young man. Such citizens as Messrs. Dean, Stallings, Dodge, Borer, Rittenhouse and others got good looks at the continental ghost as he appeared at midnight and made a careful Inspection of the gun barrels. The gentlemen claimed that the ghost, or whatever it was, acted Just as if it was looking for a lost gun, examining closely every barrel. Whenever an effort was made to approach the ghost it would disappear from sight, going into nothingness like a flash of lightning.

Every scheme possible was resorted to fathom the mystery, but all proved futile. The ghost in continental uniform endeavoring to locate a lost gun barrel from among the hundreds in the fence was in evidence at different times for a number of years, but finally ceased its midnight visits, and for more than thirty-five years has not been seen…”[4]

Of course, it’s possible that between publishing the first story in the Bee on Sept. 21, 1907 and their second story in the Star on Oct. 19, 1907, the author of these articles stumbled upon some new information. It’s also possible that the author decided to spice up an otherwise hum drum tale by connecting the fence to a bloody insurrection and a mysterious apparition… I’ll let you decide.

So, are either of these stories credible?

Based on the timeline alone, the “Revolutionary Rifle Story” looks to be bogus. Reuben Daw was, indeed, a Georgetown resident but he was born in Cornwall, England in 1808 and didn’t move to the United States until 1816.[5] It seems highly unlikely that he was purchasing bulk loads of decommissioned military equipment as an 8-year-old. Furthermore, as other scholars have noted, it is unlikely that the U.S. government made the kind of direct financial appeals to Georgetown residents, which are described in the persistent “Revolutionary Rifle Story.” It’s also a stretch to think that the War Department would have allowed residents of Washington to sift through the torched remains of the Navy Yard looking for scrap metal.[6]

In addition, while Daw is indeed the original owner of the four Gun Barrel Fence homes, this fantastic interactive map from D.C.’s Historic Preservation Office reveals that Daw’s three homes on P Street weren’t completed until 1859 and his fourth on 28th Street wasn’t completed until 1879.[7] Though it’s possible that the fence belonged to structures that previously occupied the land, that seems unlikely as the railings perfectly trace the property lines of the Daws homes.[8]

The “Hall Rifle Story” seems more plausible – at least in some respects. As detailed above, by the time of John Brown’s raid at Harpers Ferry in 1859, Daw had completed his first three homes on P and 28th Streets and, thus, might have been looking to build a fence. As census records confirm that Daw was a gunsmith, it’s tempting to think that he might have gotten a kick out of fencing his property with gun barrels.[9]

Had he attended a military auction around that time, a large quantity of Hall M1819 rifles might have been available to him. As the name suggests, the Hall breech-loading rifle was invented in 1819 but the U.S. military used Hall Rifles well into the 1850s, at which point the government sprung for newer tech and began selling off old stock. The “Hall Rifle Story” is further supported by a review of the Hall M1819’s specs. The Hall rifle barrel’s length, width, and sight locations generally mirror the fence posts.[10] (As a point of comparison, the “Revolutionary Rifle Story” is less specific about what rifle model was used in the fence.)[11]

And what about the Harpers Ferry connection? Does the fence have a connection to John Brown? That part of the story is a lot sketchier.

Although Hall Rifles were produced in Harpers Ferry, it’s unclear that Daw bought the guns from the Armory there. The military was known to advertise auctions in newspapers and no such notices for auctions at Harpers Ferry turned up in my research.[12] However, the search did unearth ads in Washington papers for other auctions, including one at Fort Monroe in 1866 and another at Philadelphia’s Navy Yard in 1867. Both of those ads specifically mention the sale of breech-loading rifles.[13] Additionally, in May 1863, The Daily National Republican published an advertisement for a Washington pawnbroker that was selling breech-loading rifles at Market Square on the corner of 9th and Pennsylvania Ave.[14] So, it seems that Daw had several opportunities — at places other than Harpers Ferry — to acquire guns for his fence.

Bottom line: When compared to the “Revolutionary Rifle Story,” the gist of the “Hall Rifle Story” seems far more likely as the origin of the Gun Barrel Fence. However, the fence’s connection to the John Brown Insurrection or the supernatural world cannot be substantiated. Regardless, it’s a pretty awesome fence and definitely worth a stroll up the corner of 28th and P St. Just don’t let the ghosts scare you.

Footnotes

- ^ “Historic Gun Barrel Fence in Georgetown,” The Washington Herald, Jun. 25, 1911, Library of Congress: Chronicling America.; “Fence made of Gun Barrels,” Popular Mechanics, Nov. 1911, 686-687.

- ^ “Muskets Beaten Into a Fence,” Popular Mechanics, Mar. 27, 1920, 20.; “Capital Sightlines,” Evening Star (Washington, D.C.), Sep. 25, 1927, Library of Congress: Chronicling America.; Dudley Harmon, “Georgetown Invites Capital Public for a Visit to Its Historic Homes,” The Washington Post, Apr. 3, 1938. ProQuest Historical Newspapers: The Washington Post.; Tom H., “Georgetown’s Gun Barrel Fence,” Ghosts of DC, Sep. 24, 2012, http://ghostsofdc.org/2012/09/24/georgetown-gun-barrel-fence/.; Elliot Carter, “Gun Barrel Fence,” Atlas Obscura, https://www.atlasobscura.com/places/gun-barrel-fence.

- ^ “A Fence of Gun Barrels,” The Washington Bee, Sep. 21, 1907, Library of Congress: Chronicling America.; “Famous Old Musket-Barrel Fence of Historic Georgetown,” Evening Star, Oct. 19, 1907, Library of Congress: Chronicling America.; “Fence of Gun Barrels Surrounds Georgetown Home,” The Washington Times, Aug. 30, 1908, Library of Congress: Chronicling America.

- ^ “Famous Old Musket-Barrel Fence of Historic Georgetown,” Evening Star.; “Fence of Gun Barrels Surrounds Georgetown Home,” The Washington Times.

- ^ “AFTER VERY MANY YEARS,” The Washington Post, Nov. 19, 1891. ProQuest Historical Newspapers: The Washington Post.

- ^ Tim Krepp, “Ghosts of Georgetown,” (Mount Pleasant S.C.: Arcadia Publishing), Part 3.

- ^ “History Quest DC,” D.C. Historic Preservation Office, https://dcgis.maps.arcgis.com/apps/webappviewer/index.html?id=4892107c0….

- ^ This 1801-1802 map of Georgetown homes shows that at least one building previously stood on the land that Daw later purchased. However, the fence, which appears to have been built within a relatively short period of time, perfectly traces the property lines of the four Daw homes, which date to 1859.

- ^ "Reuben Daw, United States Census, 1870, District of Columbia, United States; citing p. 190" FamilySearch.com, Apr. 12, 2016, https://familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:MN43-W6V.

- ^ Staff Writer, “Harpers Ferry Model 1819 (Hall Rifle) Service Long Gun/Carb,” MilitaryFactory.com, last modified Oct. 3, 2017. https://www.militaryfactory.com/smallarms/detail.asp?smallarms_id=502.

- ^ One version of the “Revolutionary Rifle Story” suggests that the fence is made of fabled Brown Bess rifles. The Brown Bess has a longer barrel length than the Hall but the hilt of the pickets are buried. Therefore, only way to confirm that the barrel definitively matches a particular rifle's barrel specs would be to tear up the fence.

- ^ A review of Maryland, Virginia, and D.C. papers did not turn up any results and military auctions were advertised relatively heavily (See the Philadelphia auction ad in the Evening Star). While it’s possible Harpers Ferry did hold an auction, it does not seem to have been widely advertised in Washington.

- ^ “Large Sale of Condemned Ordnance and Ordnance Stores,” The Daily National Republican, Feb. 03, 1866, Library of Congress: Chronicling America.: “Bureau of Ordnance” Evening Star, Mar. 28, 1867. Library of Congress: Chronicling America.

- ^ “By W. L. Wall and Co.,” The Daily National Republican, May, 29, 1863, Library of Congress: Chronicling America.

![Sketch of the mythical fuan by Pearson Scott Foresman. [Source: Wikipedia]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2023-10/Goatman_Wikipedia_Faun_2_%28PSF%29.png?h=64a074ff&itok=C9Qh-PE1)