From Crystal City to Cuba: The Tullers' International Crime Spree

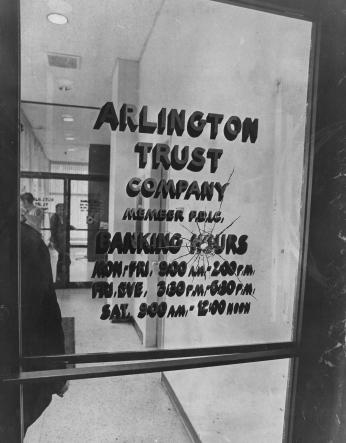

At 10:30 a.m. on October 25, 1972, two workers stepped out of a C&P Telephone van and into the Crystal City branch of the Arlington Trust Company.[1] The bank’s phones had been down for nearly half an hour and manager Henry “Bud” Candee was eager to resume normal business. He met the repairmen in the lobby and led them to a service panel at the back of the bank. Unbeknownst to Candee, the technicians were frauds. They stole the uniforms and the van and caused the phone outage by climbing down a nearby manhole and severing the bank’s phone lines.[2] But what was meant to be a relatively simple robbery, turned out to be the first act in one of the most dramatic — and bizarre — crime sprees in U.S. history.

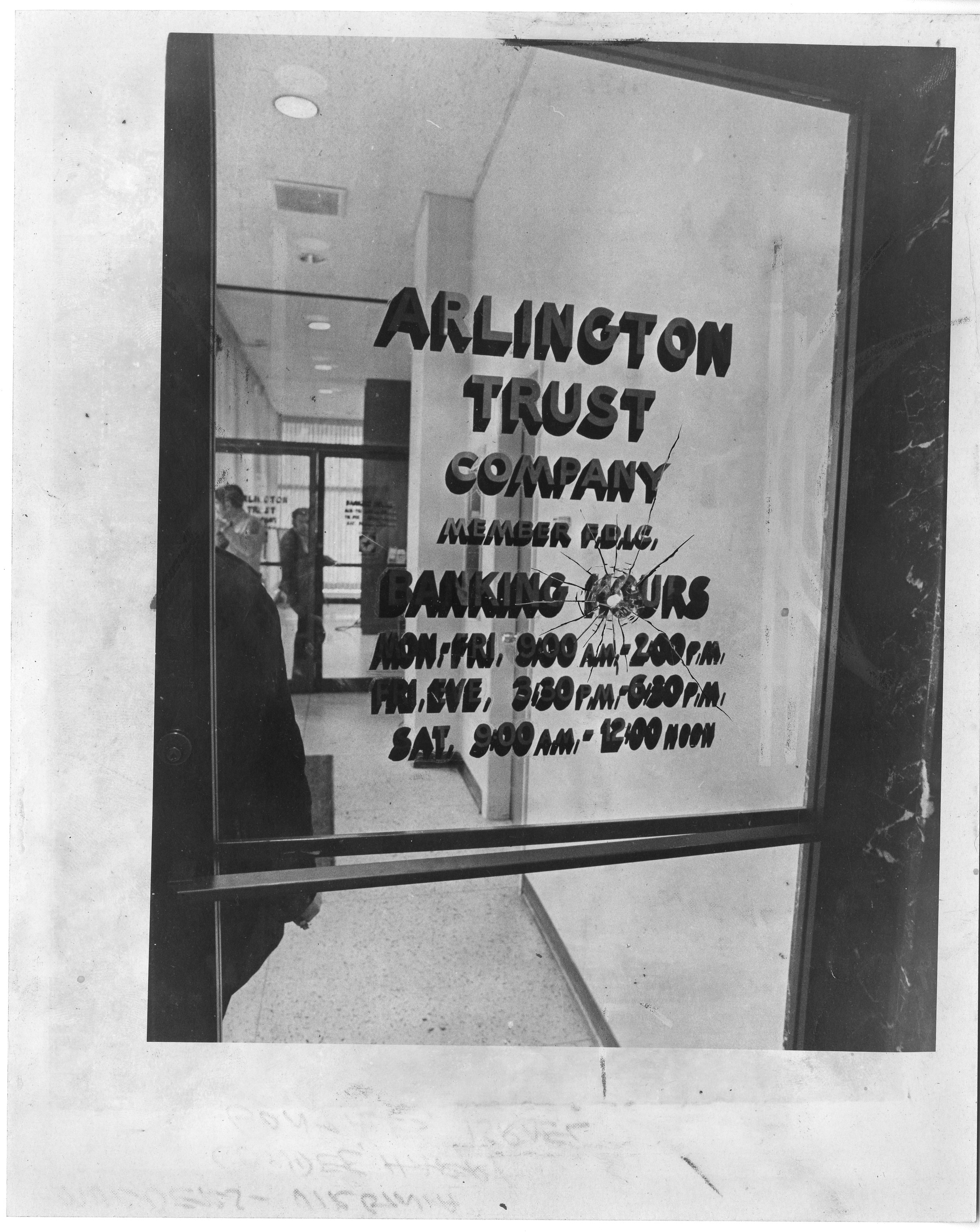

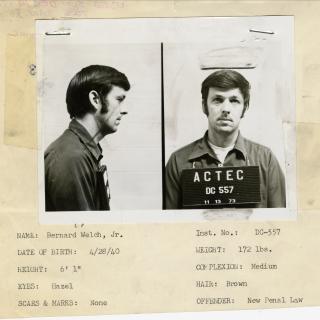

Charles Tuller had big ideas. Enraged by racial and economic inequality in the United States, the 48-year-old Alexandria native began to plan what he hoped would be a revolution. Enlisting his 19-year-old son Bryce, 18-year-old son Jonathan, and their T.C. Williams High School classmate William Graham, Charles formed a revolutionary group with grand, albeit vague, aspirations.

Though Charles had relatively ambiguous beliefs, he was most certainly anti-establishment. Concerned with systemic racism and poor socio-economic conditions in many strands of American society, Charles envisioned a grassroots movement that would upend existing power structures and establish a new, more equitable, and communally-based system of governance.

In a jailhouse interview that took place years after the robbery, Charles explained that he and the boys planned to live in the wilderness as they covertly traveled the United States inspiring local communities to take “direct action” over local affairs:

“We decided to form a group and equip ourselves so we could eventually break with our government or what is called law, and try to do something about reconstructing a new system ... we would be very security conscious and extremely mobile ... able to get to any part of the country, where we would talk with local people and find indigenous leaders ... we wanted to latch onto local situations and get people to take some kind of direct action (to) act as their own government, as their own political force ... we wanted to act as catalysts ...”[3]

Charles denied that the group was “militant” but while he claimed that “the use of arms and weapons was a defensive move,” the gang spent months stockpiling weapons and camping equipment at the Tuller home in Alexandria. Up until a week before the robbery, Charles worked as a high-level official in the Department of Commerce’s Office of Minority Business Enterprise, which allowed him to finance the group’s arsenal and camping supplies. He led the boys on numerous camping trips in the Shenandoah Valley where they tested out their survival gear and took target practice.[4]

Funding their new lives on the run became the group’s primary objective. Charles hoped selling the Tuller home and robbing the bank would provide them enough money to support their transient lifestyle and kick-start the revolution.

There was plenty of reason to believe that the heist would be successful — at least in the Tullers’ minds.

Bryce had experience working as a C&P Telephone worker and Jonathan was working as a lineman for the Virginia Electric and Power Company, and this experience undoubtedly informed the plan.[5] The Tuller boys knew cutting the lines would provide an excellent cover story that would gain them entry into the back of the bank, while also preventing anyone from calling for outside help. In addition, both Bryce and William spent time in the Army where they had learned to shoot small arms — a useful fallback should they encounter any unanticipated resistance.[6]

The plan went like this: On the morning of Oct. 25, the brothers would enter the bank in the stolen C&P uniforms. Once the manager took them to the service panel in the rear of the bank, they would show their weapons and carry out the robbery. Charles was to pose as a customer and provide support as necessary. When the deed was done, the three Tullers would exit to a waiting vehicle driven by William.[7]

Though meticulously planned, the robbery went south immediately. After opening the bank’s service panel, Bryce and Jonathan drew their pistols and informed Bud Candee of their true intentions. Much to the Tuller boys’ surprise, Candee laughed in their faces and refused to cooperate.[8] A struggle ensued and Bryce began shooting. As the shots rang out, an Arlington County police officer named Israel Gonzales entered the bank as a part of his daily beat. Gonzales ran towards the commotion and fired two shots. One shot hit Bryce in the hand and the other missed both the Tuller boys. As Bryce and Jonathan fired back at Gonzales, Charles Tuller pushed through a throng of distressed customers and shot the officer in the back.[9] The Tullers fled the bank, jumped into the getaway car, and William sped away. Both Bud Candee and Officer Gonzales were pronounced dead at the scene, while another bank employee was injured in the crossfire.[10]

It didn’t take long for law enforcement to peg the Tullers as suspects. Police found a watch engraved with Bryce’s initials under Candee’s body and a shotgun that traced back to Charles in the stolen C&P van.[11] Warrants were issued for Charles and Bryce that evening, and for Jonathan Tuller and William Graham a few days later.[12] Having found a trail of blood leading out of the bank, investigators were quite certain that one of the shooters was injured and requested that local hospitals report any unexplained gunshot wounds.

While the police believed “there was an excellent chance they [were] in the metro area,” the gang fled the DMV immediately. They swapped cars two blocks from the bank and drove south, stopping in Alabama to see if a family friend would take them in. After being turned away, the foursome went on to Houston where Charles knew a surgeon who he thought might be able to fix Bryce’s hand. They arrived in Texas to find that the surgeon had left town for the weekend.[13] Whereas everything up until the robbery had been carefully planned, the aftermath was a hectic mess.

The hapless gang decided, on a whim, to hijack a plane and take it to Cuba to escape U.S. law enforcement.[14] At 2 a.m. on Oct. 29, the men entered Houston Intercontinental Airport. Security not being what it is today, the four men had little trouble reaching the gate and stormed an Eastern Air Lines flight, shooting and killing ticketing agent Stanley Hubbard in the process. Another Eastern employee was shot three times in the arm.[15]

Once on the plane, Charles took to the cockpit and ordered the pilot fly to Cuba, while his sons and Graham stood guard over the 13 passengers who were already on board. Charles delivered monologues over the intercom throughout the flight. He continually described himself as a “white middle-class revolutionary” and declared Cuba “the only place a person could enjoy the benefits of freedom.” According to passenger Ron Pinkey, Charles also spoke directly to individual travelers on board but only addressed black and Hispanic passengers, apparently looking for “sympathetic” ears. Pinkey, the news director at D.C.’s WOL radio station, unsurprisingly described his exchange with the hijacker as “not a very pleasant experience.”[16]

Around 4 a.m., the plane was forced to land for refueling in New Orleans. Plane hijackings spiked during the 1970s and it was common for perpetrators to make a series of demands for money and supplies. However, the Tuller gang’s only instruction was that a single stripped-down worker refuel the craft. Once refueled, the plane continued on to Cuba and arrived in Havana at 5:58 a.m. There, armed Cuban guards boarded the plane, disarmed the Tuller gang, and led them off the craft. Several hours later, the pilot and passengers flew to Miami where they arrived unharmed, though no-doubt spooked by the harrowing ordeal.[17]

After getting word of the situation, both the Commonwealth of Virginia and the U.S. State Department issued requests for extradition, but Cuba was known to ignore such requests.[18](Cuba was a hot destination for air-pirates, but up until the Tullers’ arrival, the communist island nation had only ever extradited one American hijacker — an escapee from a hospital psychiatric ward.[19]) Via Swiss intermediaries, the Cubans confirmed that the captured hijackers were those implicated in the Arlington bank robbery but insisted they would only return the Tuller gang on the condition that the U.S. returned any Cubans who “illegally emigrated” to the States.[20] The U.S. Government declined and any hope of extradition fell through.

The Tuller gang’s decision to go to Cuba reinforced the hypothesis that the men were communist sympathizers. Preliminary searches of the Tuller residence turned up literature that police said suggested their involvement with “radical or militant leftist groups.” Acquaintances of Bryce, Jonathan, and Graham said that the boys often spoke favorably of Chairman Mao Tse-tung and Che Guevara.[21]

While admitting that he and his sons had “some idealist views about Cuba,” Charles Tuller firmly denied that accusations that they were communists.

“I at no time belonged to the Communist Party, and I had no desire or intention of giving my services to anything foreign ... I feel that the small farm and the small businessman, almost in a Jeffersonian sense, mixed with some kind of cooperatives that people can really participate in, is the best way for men to live in some kind of equality.”[22]

According to the elder Tuller, the group did not intend to stay in Cuba long:

“We stated when we first came into Cuba that all we wanted was treatment for Bryce’s wounds, a short rehabilitation period, and then we wanted to come back to the States. We were Americans. This was where our problem was. And my contention all along was that we did not go to Cuba to hide behind somebody else’s revolution.”[23]

However, it soon became clear to the four outlaws that they would be staying in Cuba for quite a while. Though they were originally put in jail, were soon allowed to enter Cuban society living off small stipends provided by the Cuban government. William Graham chose to integrate into Cuban society while the three Tullers resisted.[24] Graham began attending classes at Havana University and took a job as a construction worker in the Havana suburbs.[25] The Tullers viewed Graham’s decision as cowardice and unpatriotic. The father and his sons parted ways with Graham and refused to work for fear of being “Cubanized.”[26]

Any “idealistic views” the Tullers had of life in Cuba were quickly smashed. Refusing to work, the three lived in destitution. Charles came to see Cuba as a place that was dominated by Russia and the Cuban elite.[27] Bryce Tuller claimed to have witnessed numerous suicides and public executions and said that in those instances, the police would leave the bodies in public view for hours. All three Tullers fell into a deep depression.

However, in June 1974, Cuban officials approached the Tullers and told them that if they wanted to leave the country, they could. They were given a few hundred dollars each, their real travel documents and some forged documents, and were put on a Nassau-bound flight via Kingston, Jamaica.[28] William Graham stayed behind. The Tullers landed in Nassau and hopped a flight to Miami, passing through U.S. Customs undetected.[29]

Back in the United States, Charles and his sons decided to pick up where they left off.[30] They got a bus back to Virginia and promptly robbed the Super Giant Grocery in McLean, netting $1,000. The Tullers then drove down to Fayetteville, North Carolina where they staged their next hit. They targeted the local K-Mart and hatched a plan. Bryce would go into the store alone, Jonathan would stand guard outside, and Charles would wait in the gateway vehicle.[31]

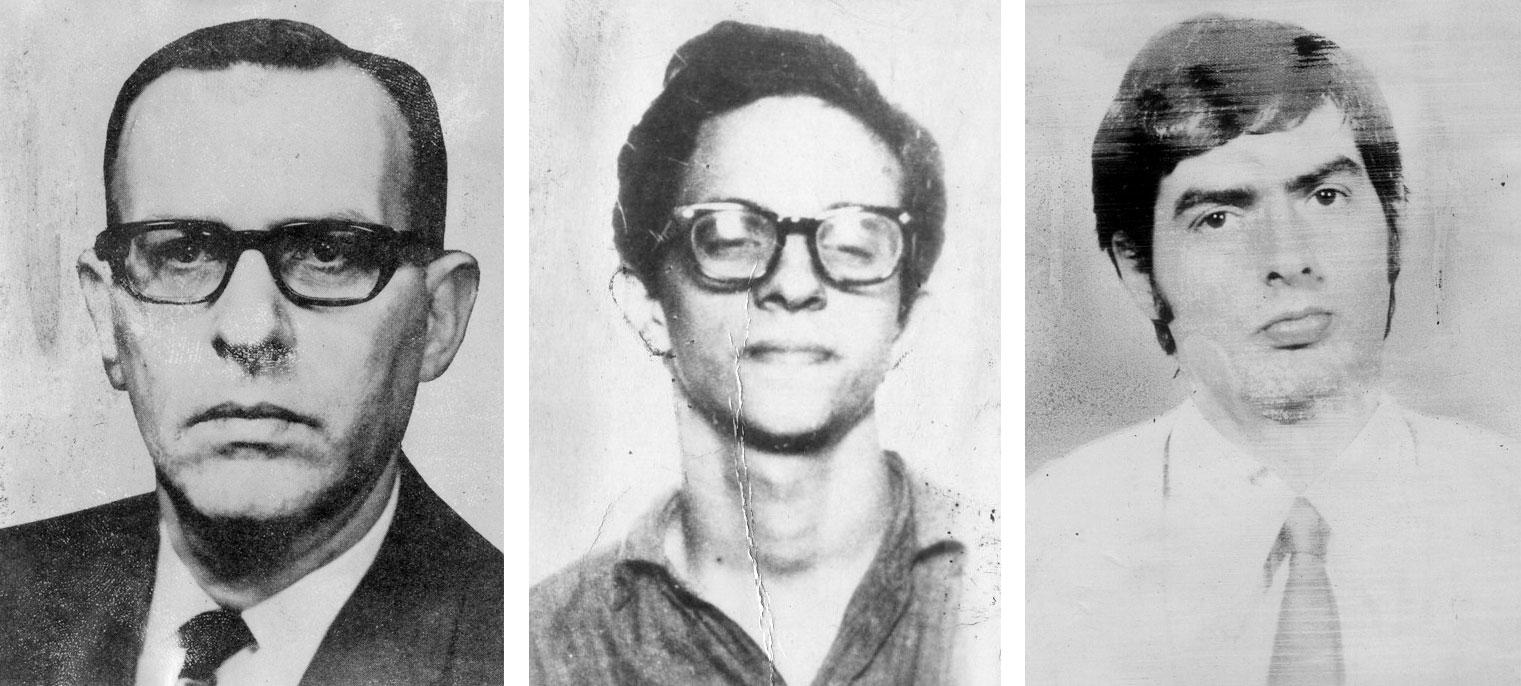

Bryce entered the store on the evening of July 3, 1975. Not long after, Jonathan heard a gunshot and abandoned his post near the front door. Jonathan ran to meet his father and the two sped off, unsure of Bryce’s fate. The three previously agreed if they were ever split up, they’d meet at the Washington Monument three days later. And so, Charles and Jonathan returned to D.C. and made their way to the monument on July 6, but Bryce failed to show. At 1 p.m. on July 7, Charles and Jonathan walked into the Old Post Office Building on Pennsylvania Avenue, where the FBI field office was then stationed. They asked the guard if they could speak to an agent and were directed up to the 5th floor where they turned themselves in.[32]

Assistant Special Agent Charles Lowie was returning from lunch when he was told that the two Tuller had just given themselves up:

“I took one look at them and said ‘that’s them.’ ... I’ve never been so surprised at anything in my life.”[33]

Charles told the agents where they’d last seen Bryce. The agents called Fayetteville and found Bryce jailed under the name “Bart Kelly.” They ordered he be extradited back to Virginia.[34] By July 1976, the Tullers had been convicted on both state and federal charges and were each sentenced to serve multiple consecutive life terms.[35]

That might have been the end of the story for the Tuller gang ... but, of course, it wasn’t. After spending eight years in prison, Bryce Tuller was back on the lam, having escaped from Bland Correctional Center in Bland County, Virginia. Then again, “escape” might be giving him a bit too much credit.

On November 28, 1984, Bryce went to the prison mailroom to send a parcel. As the officer turned to weigh the package, Bryce walked through a door that was supposed to be locked and into the main lobby of the prison. Unnoticed, he continued out the front door.[36] Once outside, Bryce fled to the nearby hills. As it turned out, his escape was short-lived. Two days later, was found walking along I-77. Cold and hungry, Bryce did not resist arrest.[37]

While the three Tullers all went down at once, William Graham wasn’t brought to court until almost two decades later. Graham left Cuba around 1978 and moved to San Francisco, where he worked for 15 years as a computer technician under the assumed name Morgan Richards. Graham/Richards had made a nice life for himself. His friends found him to be kind and giving and he was the leader of the local softball league. He only turned himself in once the FBI threatened to prosecute his family whom they suspected of aiding William.[38] Graham was sentenced to two concurrent life sentences (as opposed to consecutive sentences like Charles, Bryce, and Jonathan Tuller) on the basis that he had a lesser role in the gang’s various crimes.[39]

Finally, over 20 years after the robbery and murders in Crystal City, the case was brought to a close.

Charles Tuller died of a heart attack in 1987.[40] Charles’ eldest son, Bryce, died in prison sometime between February 2015 and February 2016.[41] The youngest Tuller, Jonathan, remains locked up in Buckingham Correctional Center.[42] As of 2013, William Graham was still in prison and was a subject of KCRW's Unfictional documentary series.

Footnotes

- ^ Jay Mathews, “Two Slain in Arlington Bank Holdup,” Washington Post, Oct. 26, 1972. ProQuest Historical Newspapers.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Eugene L. Meyer, “Slayer 'Did It With Honor',” Washington Post, Oct. 26, 1975. ProQuest Historical Newspapers.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Jay Mathews and Kenneth Bredemeier, “2d Tuller Son Is Suspect in Jet Hijacking,” Washington Post, Oct. 31, 1972. ProQuest Historical Newspapers.; Meyer, “’Slayer Did It With Honor’”

- ^ Meyer, “’Slayer Did It With Honor’.”

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Deborah Sue Yaeger, “3 Tullers Plead Guilty to Killings,” Washington Post, Sept. 23, 1975. ProQuest Historical Newspapers.; Meyer, “’Slayer Did It With Honor’”

- ^ Mathews, “Two Slain in Arlington Bank Holdup.”

- ^ Mathews and Bredemeier, “2d Tuller Son Is Suspect in Jet Hijacking.”

- ^ Mathews and Bredemeier, “2d Tuller Son Is Suspect in Jet Hijacking.”; Mathews, “Two Slain in Arlington Bank Holdup.”

- ^ Mathews, “Two Slain in Arlington Bank Holdup.”; Jay Mathews, “Car Found, Linked To Bank Slayings,” Washington Post, Oct. 28, 1972. ProQuest Historical Newspapers.; Meyer, “’Slayer Did It With Honor’.”

- ^ Meyer, “’Slayer Did It With Honor’.”

- ^ Nancy Scannell and Charles A. Krause, “3 Va. Men Charged In Hijack: Bank Slaying Suspects Take Plane to Cuba,” Washington Post, Oct. 30, 1972. ProQuest Historical Newspapers.

- ^ Paul G. Edwards and Jay Mathews, “Cuba Seizes 4 in Houston Hijacking,” Washington Post, Nov. 1, 1972. ProQuest Historical Newspapers.

- ^ Scannell and Krause, “3 Va. Men Charged In Hijack: Bank Slaying Suspects Take Plane to Cuba.”

- ^ Jay Mathews, “Arlington Slaying Suspects Were Hijackers, Cuba Says,” Washington Post, Nov.. 7, 1972. ProQuest Historical Newspapers.; “Extradition Effort Started by Virginia,” The Washington Post, Nov. 18, 1972. ProQuest Historical Newspapers.

- ^ Mathews and Bredemeier, “2d Tuller Son Is Suspect in Jet Hijacking.”

- ^ Mathews, “Arlington Slaying Suspects Were Hijackers, Cuba Says.”

- ^ Mathews and Bredemeier, “2d Tuller Son Is Suspect in Jet Hijacking.”

- ^ Meyer, “’Slayer Did It With Honor’.”

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Nancy Scannell and Charles A. Krause, “3 Va. Men Charged In Hijack: Bank Slaying Suspects Take Plane to Cuba,” Washington Post, Oct. 30, 1972. ProQuest Historical Newspapers.

- ^ Paul G. Edwards and Jay Mathews, “Cuba Seizes 4 in Houston Hijacking,” Washington Post, Nov. 1, 1972. ProQuest Historical Newspapers.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Ron Shaffer and Athelia Knight, “Tullers Chose to Risk Jail Rather Than Live in Cuba,’ Washington Post, Jul. 15, 1975. ProQuest Historical Newspapers.

- ^ Meyer, “’Slayer Did It With Honor’.”

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Alfred E. Lewis and Jay Mathews, “Father, Son Give Up in '72 Killings,’ Washington Post, Jul. 8, 1975. ProQuest Historical Newspapers.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ “3 Tullers Get 100 Years In Hijacking,” Washington Post, Jul 17, 1976. ProQuest Historical Newspapers.

- ^ Nancy Lewis and Tom Sherwood, “Slayer-Hijacker Walks Away From Va. State Prison,” Washington Post, Nov. 29, 1984. ProQuest Historical Newspapers.

- ^ Molly Moore, “Va. Prison Boss Order Changes,” Washington Post, Dec. 1, 1984. ProQuest Historical Newspapers.

- ^ Howe, “Years Later, Bank Killing Haunts Many.”

- ^ Charles W. Hall, “Ex-Fugitive Gets Life for 1972 Crimes,” Washington Post, Dec. 11, 1993. ProQuest Historical Newspapers.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Bryce Tuller was denied parole in February 2012 (https://vpb.virginia.gov/files/1025/vpb-decisions-feb12.pdf) , February 2013 (https://vpb.virginia.gov/files/1119/vpb-decisions-feb13.pdf), February 2014 (https://vpb.virginia.gov/files/1007/vpb-decisions-feb14.pdf), and February 2015 (https://vpb.virginia.gov/files/1102/vpb-decisions-feb15.pdf). His parole hearing scheduled for February 2016 (https://vpb.virginia.gov/files/1116/vpb-decisions-feb16.pdf) never took place and a VA. DOC (https://vadoc.virginia.gov/offenders/locator/index.aspx) search for “Bryce Matthew Tuller” Offender Number “1165065” does not turn up a result.

- ^ https://vadoc.virginia.gov/offenders/locator/index.aspx Search “Jonathan Tuller” or by Offender Number “1068596”

![Sketch of the mythical fuan by Pearson Scott Foresman. [Source: Wikipedia]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2023-10/Goatman_Wikipedia_Faun_2_%28PSF%29.png?h=64a074ff&itok=C9Qh-PE1)