John Wilkes Booth's Abduction Plot Gone Wrong

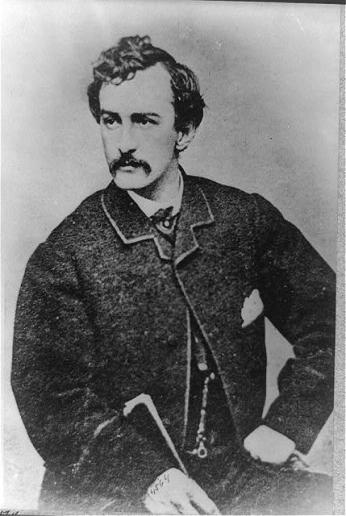

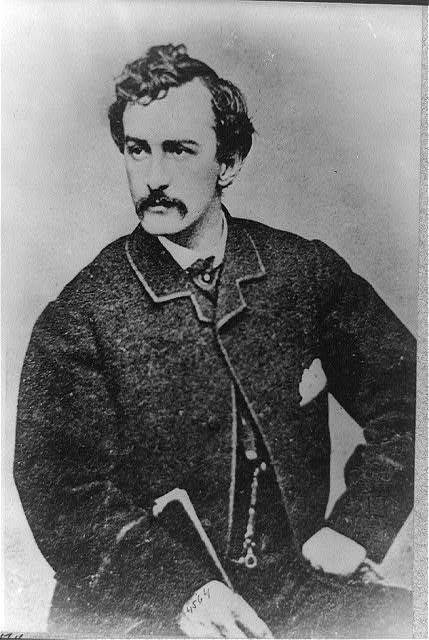

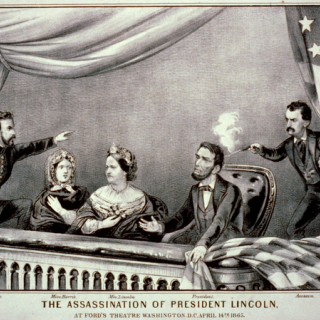

The story is well known: on April 14, 1865, actor John Wilkes Booth assassinated President Abraham Lincoln at Ford’s Theater. Lincoln died the next morning in a boarding house across from the theater. Booth escaped – temporarily – but was shot 12 days later in Virginia.[1]

What is lesser known is that Booth did not always plan on killing Lincoln. In fact, the actor’s original plan was not to strike a fatal blow. He wanted to abduct Lincoln, take him to Richmond and exchange him for Confederate soldiers then held in Union prisons.

As Booth wrote to his brother-in-law, John S. Clarke, on November 25, 1864: “My love (as things stand to-day) is for the South alone. Nor do I deem it a dishonor in attempting to make for her a prisoner of this man to whom she owes so much misery.”[2]

In 1864, General Ulysses S. Grant had stopped all prisoner exchange between the Union and the Confederacy in an attempt to decrease the Confederacy's military capability.[3] The Confederacy did not have as much man power as the Union, so every soldier counted. Booth said as much to would-be co-conspirator John Surratt: “We cannot spare one man, whereas the United States government is willing to let their own soldiers remain in our prisons because she has no need of the men. I have a proposition to submit to you, which I think if we can carry out will bring about the desired exchange.”[4]

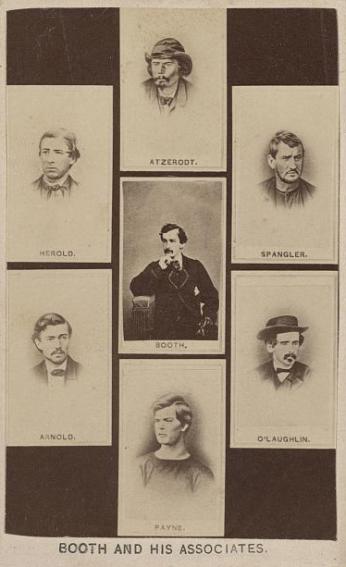

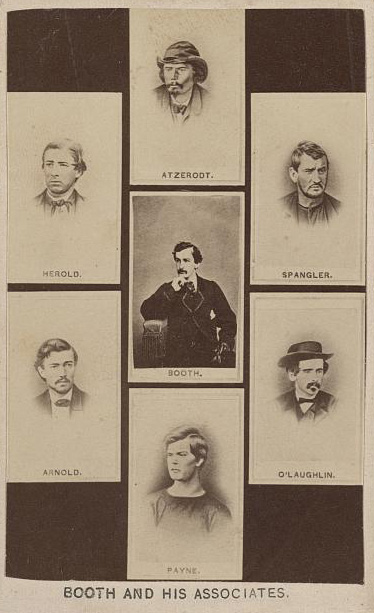

To carry out his plan, Booth enlisted the help of six men: Surratt, Samuel Arnold, George A. Atzerodt, Michael O’Laughlin, David E. Herold and Lewis Powell (Payne).

They all had a specific skill or knowledge, which made them an asset to the team. Arnold and O’Laughlin were old friends of Booth. Atzerodt was known for helping Confederate spies across the Potomac River. Surratt often helped the Confederate secret service, and knew all about the secret routes in Southern Maryland used by Confederate spies to enter and leave Washington. Powell had the physical strength to overwhelm the 6’4” president. Herold knew the poorly mapped routes that existed below D.C.[5]

The men were motivated by an undying loyalty to the Confederacy – something to which even those loyal to the Union might relate, as John Surratt opined years later.

“And now reverse the case. Where is there a young man in the North with one spark of patriotism in his heart who would not have with enthusiastic ardor joined in any undertaking for the capture of Jefferson Davis and brought him to Washington? There is not one who could have not done so. And so I was led on by a sincere desire to assist the South in gaining her independence.”[6]

One plan was to capture Lincoln while he was watching a play in Ford’s Theater. They would kidnap the President in his box, lower him onto the stage and carry him out of the theater. This plan was never carried out as some of the men deemed it unfeasible.[7]

Another plot was to capture the President while he was traveling to the Soldiers’ Home. Located several miles from the White House in what was then the rural Washington County part of the District, the Soldiers’ Home was Lincoln’s main residence during the hot summer months. The President would often take a carriage there with little or no protection, making him a vulnerable target.[8]

These were not the only plots to kidnap Lincoln. Two members of the Confederacy army also had plans to abduct the President. One was Joseph Walker Taylor, the nephew of former president Zachary Taylor. The other was Colonel Bradley T. Johnson. Neither was carried out and it is unknown whether Booth knew about them.[9]

Even as they schemed, Booth and his conspirators were on the lookout for new opportunities. On March 17, 1865, Booth was told the President was going to the Campbell Military Hospital to see a play.[10]

As Surratt remembered, “The report only reached us about three quarters of an hour before the time appointed, but so perfect was our communication that we were instantly in our saddles on the way to the hospital.”[11]

The group met at a nearby restaurant to iron out the details. They would stop the carriage as Lincoln returned home after the play, and overpower the President and his driver. Both men would be handcuffed and taken across the Potomac River through Southern Maryland.[12]

“We felt confident that all the cavalry in the city could never overhaul us,” Surrat explained. The group had quick horses, knowledge of the countryside and had planned of getting rid of the carriage once they were out of D.C.[13]

After the meeting, Booth decided to go to the hospital to make sure everything was set. To his surprise and disappointment, Lincoln was not there. It turned out the President was at a ceremony in the National Hotel.[14]

After this failed attempt, some in the group gave up. As Surratt explained, “We soon after this became convinced that we could not remain much longer undiscovered, and that we must abandon our enterprise.”[15] He left Washington and was in Canada by mid-April.[16] Likewise, Arnold and O’Laughlin left D.C. and returned to their homes in Baltimore.[17] Neither was involved in the assassination.[18]

When he was planning the abduction, Booth showed few signs of wanting to kill the President. Only once did he hint at this when meeting with his group. The idea was turned down quickly and Booth excused himself saying that he “had drank too much champagne.”[19]

However, after the failure to carry out the abduction plot in March and Union’s capture of Richmond in early April, Booth’s attitude apparently changed. Thomas T. Eckert, the assistant Secretary of War from 1865 to 1867, testified that Powell said Booth showed his intent to murder the President during the celebration that followed the fall of Richmond.

“The President made a speech that night from one of the windows of the White House, and he [Powell] and Booth were in the grounds in front,” Ecker said. “Booth tried to persuade him to shoot the President while in the window, but he told Booth he would take no such risk; that he left then and walked around the square, and that Booth remarked: ‘That is the last speech he will ever make.’”[20]

As we know, Booth and the remaining co-conspirators carried out the assassination plot on the evening of April 14, 1865.[21] As he ran from the theater that night, Booth left behind some personal effects, including a letter from Arnold, urging patience:

“Time more propitious will arrive yet. Do not act rashly or in haste,” Arnold wrote. "Weigh all I have said, and, as a rational man and a friend, you can not censure or upbraid my conduct. I sincerely trust this, nor aught else that shall or may occur, will ever be an obstacle to obliterate our former friendship and attachment.”[22]

Booth, it seems, felt that the time for patience had passed.

Footnotes

- ^ History.com Staff. Abraham Lincoln’s Assassination. 2009 http://www.history.com/topics/abraham-lincoln-assassination

- ^ Wilson, Francis. John Wilkes Booth: Fact and Fiction of Lincoln's Assassination. Houghton Mifflin Company, 1929. pp. 54

- ^ Steers, Edwards. The Name is Still Mudd. Thomas Publications, 1997. pp. 17

- ^ Washington Evening Star. "A Remarkable Lecture: John H. Surratt Tells His Story." Washington Evening Star December 7, 1870.

- ^ Donald, David Herbert. Lincoln. Touchstone, 1995. pp. 587

- ^ Washington Evening Star. "A Remarkable Lecture: John H. Surratt Tells His Story." Washington Evening Star December 7, 1870.

- ^ Edwards, William C. The Lincoln Assassination - The Rewards Files. 2012. pp. 95

- ^ Tidwell, William A. Come Retribution: the Confederate Secret Service and the Assassination of Lincoln. University of Mississippi, 1988. pp. 264

- ^ Steers, Edwards. The Name is Still Mudd. Thomas Publications, 1997. pp. 10

- ^ Tidwell, William A. Come Retribution: the Confederate Secret Service and the Assassination of Lincoln. University of Mississippi, 1988. pp. 414

- ^ Washington Evening Star. "A Remarkable Lecture: John H. Surratt Tells His Story." Washington Evening Star December 7, 1870.

- ^ Tidwell, William A. Come Retribution: the Confederate Secret Service and the Assassination of Lincoln. University of Mississippi, 1988. pp. 414

- ^ Washington Evening Star. "A Remarkable Lecture: John H. Surratt Tells His Story." Washington Evening Star December 7, 1870.

- ^ Tidwell, William A. Come Retribution: the Confederate Secret Service and the Assassination of Lincoln. University of Mississippi, 1988. pp. 414

- ^ Washington Evening Star. "A Remarkable Lecture: John H. Surratt Tells His Story." Washington Evening Star December 7, 1870.

- ^ Ford's Theater. Lincoln's Assassination. https://www.fords.org/lincolns-assassination/

- ^ Tidwell, William A. Come Retribution: the Confederate Secret Service and the Assassination of Lincoln. University of Mississippi, 1988. pp. 414

- ^ Ford's Theater. Lincoln's Assassination. https://www.fords.org/lincolns-assassination/

- ^ Washington Evening Star. "A Remarkable Lecture: John H. Surratt Tells His Story." Washington Evening Star December 7, 1870.

- ^ McPherson, Edward. Testimony taken before the Judiciary Committee of the House of Representatives in the investigation of the charges against Andrew Johnson. second session Thirty-ninth Congress, and first session Fortieth Congress, 1867. Clerks Office, House of Representatives, 1867. pp. 674

- ^ Ford's Theater. Lincoln's Assassination. https://www.fords.org/lincolns-assassination/ According to Ford’s Theatre’s exhibit, Michael O’Laughlin was unaware that the plot had shifted from abduction to assassination. After the murder, O’Laughlin turned himself in to authorities. He was sentenced to life in prison while Powell, Herold, Atzerodt and Mary Surratt were executed.

- ^ Herold, David E., et al. The assassination of President Lincoln and the trial of the conspirators David E. Herold, Mary E. Surratt, Lewis Payne, George A. Atzerodt, Edward Spangler, Samuel A. Mudd, Samuel Arnold, Michael O'Laughlin. Compiled and arranged by Benn Pitman, recorder. Moore, Wilstach & Baldwin, 1865. pp. 388

![Sketch of the mythical fuan by Pearson Scott Foresman. [Source: Wikipedia]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2023-10/Goatman_Wikipedia_Faun_2_%28PSF%29.png?h=64a074ff&itok=C9Qh-PE1)