Lansburgh Corners the Market on Black Crêpe

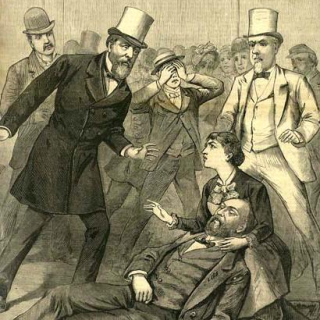

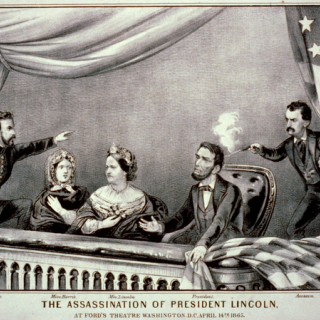

April 14th, 1865 marks the date of one of the most shocking and memorable events in Washington and American history: the assassination of Abraham Lincoln. The President was shot at 10:15 p.m., and by 10:20 p.m., word had already left Ford’s Theater and spread throughout the District. By 10:30 p.m., the President’s death was looking imminent, and after hearing this news just two blocks over at 7th and D Streets NW, Gustave Lansburgh, owner of Lansburgh & Bros. Fancy Goods Agency, decided to start decorating his store in mourning black. It was this small decision that would transform Lansburgh’s dry goods store into one of the most prosperous Washington department stores for the next 113 years.

Gustave Lansburgh, a Jewish German immigrant born in Hamburg, Germany in 1839, came to the United States with his brothers James and Max in 1854.[1] After receiving education in Baltimore, Lansburgh worked as a clerk in a dry goods store. Just a few years later, Gustave and James opened their own dry goods store in Baltimore which quickly acquired a positive reputation for “fair dealing.”[2]

After saving a few hundred dollars, Gustave came to Washington where he opened up a small stand in the former Center Market—located near the present site of the National Archives. While in Center Market, Lansburgh sold “collar buttons, pins, shoestrings and a variety of other small articles which did not require the outlay of much capital and which he knew the market people would buy.”[3] It seemed, however, that his stand was consistently overlooked. Gustave decided to try a new way of selling his goods—he would set off on foot and carry the items in a large pack on his back.

Gustave brought his brother Max down from Baltimore to run the stand in Center Market, and then set off, often walking the lengths of the city in a day.[4] After doing this successfully for several years, Gustave and Max opened up their first business on the second floor of the National Bank of Washington building on 7th Street NW.[5]

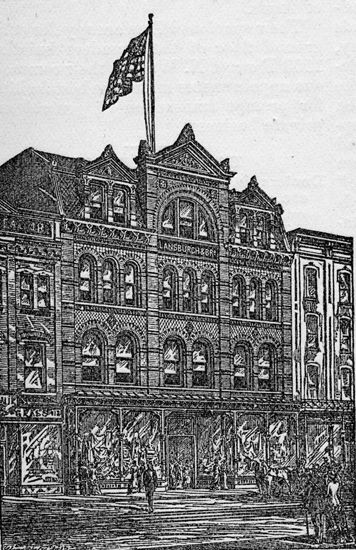

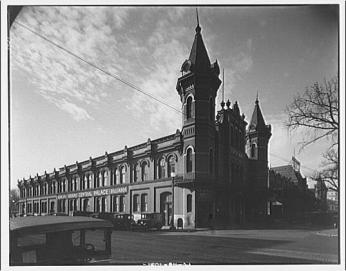

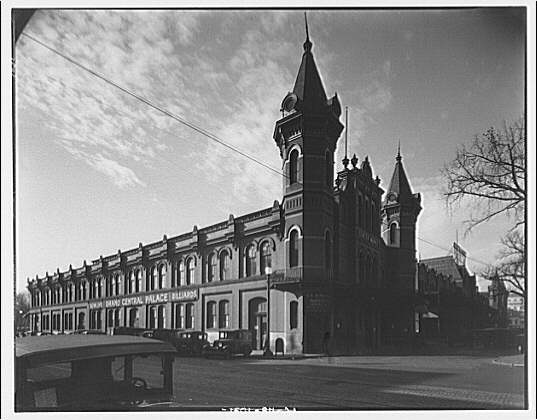

The Lansburghs’ store slowly started gaining the same reputation for fair dealing in Washington as it had earned in Baltimore, and the brothers were able to open two new freestanding locations on 7th Street: one just above D Street, and the other further up 7th near the present day Gallery Place.

From about 1860 through the Civil War, Lansburgh’s store prospered on 7th Street. While continuing to sell dry goods, Lansburgh expanded his offerings to include “oil cloths, [and the] manufacture of cloaks and mantillas and similar articles.”[6] By the time of General Lee’s surrender at Appomattox on April 9, 1865, the Lansburghs were enjoying a growing prestige in Washington. It was Lincoln’s assassination just four days later, however, that would launch Lansburgh’s into widespread notoriety and success.

Gustave, working in his 7th Street store a few blocks over from Ford’s Theatre, heard the news of the President’s fate around 10:30 p.m. on the night of April 14, 1865. He made the decision to start decorating his store windows in mourning black, but was frustrated to find that he did not have enough black fabric to cover the whole store.[7] Knowing he couldn’t afford to waste any time, he immediately set off to Baltimore to procure the necessary black material. While in Baltimore, Lansburgh judiciously considered that there might be a high demand for black fabric in the coming days, so he bought every piece he could find throughout the city.[8] With hundreds of yards of black material, he traveled through the night in order to make it back to Washington by early morning, and at 7:22 a.m. that morning, Lincoln died.

In the coming days, the government encouraged D.C. merchants to “drape their buildings in black,” and Washingtonians discovered that the only black crepe to be found was at the Lansburgh & Bro. dry goods store.[9] Lansburgh had cornered the market on black fabric, but in keeping with his reputation for fair and friendly business, he gave this black crepe away at no cost.[10] Businesses, homes, government agencies, and “even the engine and railroad cars that carried the martyred president to his grave in Springfield, Ill., [were] draped in Lansburgh crepe.”[11] In fact, every piece of draped black fabric featured in every photograph of Washington’s mourning and Lincoln’s funeral was provided by Lansburgh & Bro.[12]

This honorable action bode well for the Lansburghs in coming years. The name of the store became instantly well-known and attracted shoppers from all over the District. Unable to forget what the Lansburgh’s had done to honor Lincoln, government agencies seemed to form an allegiance to the store and often established contracts with them that no doubt helped the business soar financially.[13] This new business boom allowed the brothers, now Gustave and James, to close the store on upper 7th Street, and focus on expanding the store at 7th and D into the length of nearly the entire block.

Because department stores were becoming popular in the 1880’s, the Lansburgh brothers decided to give the new concept a try in their extended 7th Street location. They added fabrics and ready-made garments to their popular stock of dry goods, and found a massive crowd anxious to enter the new department store on its October 2, 1882 opening (a crowd so excited they broke multiple show windows on the way in).[14]

Despite the arrival of other department stores in Washington—most notably Woodward & Lothrop—Lansburgh’s continually won-over shoppers with innovative concepts. They boasted ownership of the District’s first wooden elevator in a commercial building, which an 1882 Washington Post described as “an improved Otis, noiseless and absolutely safe.”[15] The Lansburghs also had the revolutionary idea to move their fabric department to the top floor of the store and install a skylight, so that women could see the actual colors of their fabrics in natural light.[16]

New ideas and technologies like these allowed Lansburgh’s to enjoy prosperous and loyal business in Washington for the better part of the next 90 years. When the 1968 riots destroyed much of the downtown area, however, Lansburgh’s found itself to be one of the businesses struggling to recover and stay relevant—its closing day came in the spring of 1973. The Washington Post remarked, “There is a need for crepe at Lansburgh’s again, but this time the burial is that of the 113-year-old department store itself.”[17]

The city of Washington would go on to turn the old Lansburgh’s store into a development project of apartments, shops, and a large theatre to be known as the Lansburgh Theatre—which has been owned and occupied by the Shakespeare Theatre Company since 1991.

Gustave Lansburgh, who ran the store until his death in 1911, may not have known at the time that his generous 1865 actions in providing the black crepe for Lincoln’s funeral would be so beneficial for his business, but for 113 years, “Lansburgh” was a Washington household name, and was “as closely identified with the people of the city as the Capitol."[18]

Footnotes

- ^ The Washington Post (1877-1922); Washington, D.C. 1911. “AGED MERCHANT DEAD: Gustave Lansburgh in Business Here Over Fifty Years,” April 24, 1911. https://search-proquest-com.library.access.arlingtonva.us/hnpwashington….

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ McDONNELL, BERNARD. 1925. “ROMANCES OF WASHINGTON STORES: Lansburgh & Bro.” The Washington Post (1923-1954); Washington, D.C., October 11, 1925, sec. AMUSEMENTS FEATURES. https://search-proquest-com.library.access.arlingtonva.us/hnpwashington….

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Baker, Donald. 1973. “As D.C.’s Oldest Department Store Prepares to Close: Analyzing Lansburgh’s Shutdown.” The Washington Post, Times Herald (1959-1973); Washington, D.C., April 29, 1973, sec. BUSINESS & FINANCE. https://search.proquest.com/docview/148433830/abstract/64E1CDD95714B63P….

- ^ SmithsonianAnacostia. 2015. Sam Brylawski, Descendant of Store Owner, James Lansburgh. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=KKC9VrKo3HQ.

- ^ Baker, Donald. 1973. “As D.C.’s Oldest Department Store Prepares to Close: Analyzing Lansburgh’s Shutdown.” The Washington Post, Times Herald (1959-1973); Washington, D.C., April 29, 1973, sec. BUSINESS & FINANCE. https://search.proquest.com/docview/148433830/abstract/64E1CDD95714B63P….

- ^ SmithsonianAnacostia. 2015. Sam Brylawski, Descendant of Store Owner, James Lansburgh. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=KKC9VrKo3HQ.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ The Washington Post (1877-1922); Washington, D.C. 1882. “LANSBURGH’S NEW BUILDING.: A Magnificent Store Erected on Sev- Enth Street.,” October 1, 1882. https://search-proquest-com.library.access.arlingtonva.us/hnpwashington….

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Baker, Donald. 1973. “As D.C.’s Oldest Department Store Prepares to Close: Analyzing Lansburgh’s Shutdown.” The Washington Post, Times Herald (1959-1973); Washington, D.C., April 29, 1973, sec. BUSINESS & FINANCE. https://search.proquest.com/docview/148433830/abstract/64E1CDD95714B63P….

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ The Washington Post (1877-1922); Washington, D.C. 1911. “AGED MERCHANT DEAD: Gustave Lansburgh in Business Here Over Fifty Years,” April 24, 1911. https://search-proquest-com.library.access.arlingtonva.us/hnpwashington….

![“Lincoln’s funeral on Pennsylvania Ave.” (Photo Source: Library of Congress) Lincoln's funeral on Pennsylvania Ave. Washington D.C, 1865. [Washington, D.C.:] Photograph. https://www.loc.gov/item/2017897828/. “Lincoln’s funeral on Pennsylvania Ave.” (Photo Source: Library of Congress) Lincoln's funeral on Pennsylvania Ave. Washington D.C, 1865. [Washington, D.C.:] Photograph. https://www.loc.gov/item/2017897828/.](/sites/default/files/styles/embed/public/03254v.jpg?itok=f6TuNLnY)

![“Lincoln’s funeral on Pennsylvania Ave.” (Photo Source: Library of Congress) Lincoln's funeral on Pennsylvania Ave. Washington D.C, 1865. [Washington, D.C.:] Photograph. https://www.loc.gov/item/2017897828/. “Lincoln’s funeral on Pennsylvania Ave.” (Photo Source: Library of Congress) Lincoln's funeral on Pennsylvania Ave. Washington D.C, 1865. [Washington, D.C.:] Photograph. https://www.loc.gov/item/2017897828/.](/sites/default/files/03254v.jpg)

![Sketch of the mythical fuan by Pearson Scott Foresman. [Source: Wikipedia]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2023-10/Goatman_Wikipedia_Faun_2_%28PSF%29.png?h=64a074ff&itok=C9Qh-PE1)