A Dog’s Life for Laddie Boy

As each President-elect prepares to move into the White House, speculation begins on everything from Cabinet appointments to whether a new china pattern will be picked to serve at state dinners. But one of the biggest questions in more recent years has come to the forefront.

Will the First Family bring a pet?

Presidential pets, from puppies to parakeets, aren’t just cute animals once they enter the Executive Mansion. Many become media and public relations ambassadors, from “unofficial war dog”[1] Fala Roosevelt, who headed the ‘Barkers for Britain’ efforts during World War II, to Millie Bush, whose eponymous children’s book "Millie’s Book" stayed on top of best-seller lists for months.[2] Decades after Richard Nixon’s famous “Checkers” speech, another Nixon dog named King Timahoe appeared on the 1971 CBS News special “Christmas at the White House.”[3]Socks and Buddy Clinton “helped” sign Christmas cards. Barney Bush starred in multiple scripted “Barney Cam” videos — perhaps you might remember the 2007 crowd-pleaser, “My Barney Valentine.”[4]

Pets — especially dogs — can also be gifts of goodwill: Nikita Khrushchev sent a puppy named Pushinka (Russian for “Fluffy”) to the Kennedy family, while Jimmy Carter’s daughter Amy received a puppy she named Grits not long after she moved into the White House.

Even more exotic animals have made their way into the presidential residence: Rebecca the raccoon lived with the Coolidges, while Woodrow Wilson kept a flock of sheep on the White House lawn during World War I. Even those who didn’t stay very long, like Calvin Coolidge’s hippo Billy, James Buchanan’s herd of elephants, or Martin Van Buren’s pair of tiger cubs (which Congress demanded be sent to a zoo), have gotten attention in some way or another.[5] [6] [7]

But the media coverage modern Presidential pets have come to enjoy is a more recent development. Whether the animals in residence were hippos, tigers, sheep, or just normal cats or dogs, they only got brief, passing mentions — they just weren’t seen as particularly good news-copy.

This changed with Laddie Boy.

You may not recognize the name now, but Laddie Boy was a superstar in his day. An Airedale Terrier, Laddie Boy was born July 26, 1920 at Caswell Kennels, in Toledo, Ohio.[8] When, at seven months old, he began his fateful journey to the White House, there was no indication that he was about to embark on a whirlwind two years of fame and fortune. Sent as a gift to Warren Harding, Laddie Boy was the son of a champion, but he would almost immediately eclipse his well-known dad.

“While no one remembers him today, Laddie Boy’s contemporary fame puts Roosevelt’s Fala, LBJ’s beagles, and Barney Bush in the shade […] That dog got a huge amount of attention in the press. There have been famous dogs since, but never anything like this.” – Tom Crouch, historian, Smithsonian Institute[9]

It started with a Cabinet meeting: President Harding got word that Laddie Boy had arrived, and he hastily left to go meet the new pup. Soon, Harding and Laddie Boy were inseparable, and Laddie Boy was given his own hand-carved chair so he could sit in on the meetings himself.[10] [11] The White House News Photographers Association, which had only recently been allowed a room inside the White House, found him an excellent subject, often capturing him playing with the President. This was fine by Harding — he was a former newspaper publisher, and he knew the positive power of a picture, becoming “the first to have a widely photographed White House pet.”[12]

It didn’t take long for the Laddie Boy craze to boom. Adoptions of Airedale Terriers skyrocketed. His canine relatives' capers made front-page news across the country.[13] [14] Arguments over who truly gifted Laddie Boy to the President got heated as more than one person tried to take credit.[15] A thousand bronze miniatures of him were made and the President handed them out “like a proud father handing out cigars to celebrate the birth of a child”[16] to select supporters in both Washington, D.C. and in Harding’s home state of Ohio. In fact, the right to display these miniatures was highly sought; one of the only Washington businesses permitted to do so was a jewelry firm named Galt & Brother, on Pennsylvania Avenue — whose lady proprietor you may know: Edith Bolling Galt Wilson, second wife of Woodrow Wilson.[17] Invitations to Laddie Boy’s birthday parties — complete with dog biscuit cake — were coveted by both pedigreed pooches and more modest mongrels. His social calendar was of great interest: for example, he brought his star-power to the “Be Kind to Animals” parade in May 1921, as well as an accompanying performance.[18] [19] [20] [21] In 1922, much was made of Laddie Boy's attending the annual White House Easter Egg Roll as he did tricks for the crowd, then went around “sniffing youngsters and shaking hands.”[22] In fact, when the Hardings had a conflicting engagement in 1923, Laddie Boy hosted the Easter Egg Roll himself, delighting the congregated children.[23]

But most importantly, Laddie Boy became his own sort of politician. The title “First Dog,” enjoyed most recently by Sunny and Bo Obama, originated with Laddie Boy. He was a personable dog, but he was also “a welcome distraction in the sober White House environment.”[24]Harding enjoyed good popularity ratings, but members of his administration — like the “Ohio Gang” — left blemishes on his reputation. Since he had been in the newspaper business, he knew the media wanted material they could use. At the same time, he could “cultivate a persona of humanness and warmth and approachability” that his predecessor Wilson had never managed.[25] [26] Much had been made of Mrs. Harding’s efforts to bring “an atmosphere of simplicity, of democracy and warm hearted welcome”[27] to the White House, not least by throwing open the doors to visitors — but Harding wanted to continue to cement a positive image.

So, the President and his advisors unleashed (get it?) Laddie Boy to the papers. His first major interview appeared in the editorial section of the Evening Star on July 17, 1921, where it was promised that he would address “some of the Prominent Questions of the Hour.”

“I have consented to be interviewed because it is a duty I feel I owe the public, and while I am establishing a precedent, I trust that in the years to come I will not be called upon again to discuss any public questions. The position I occupy is a most peculiar one and I have to be very diplomatic in everything I do […] I not only attend the Cabinet meetings, but also enjoy many hours of the President’s company…”[28]

There were complimentary comments about Mrs. Harding, of course, as well as “Dog Man” Wilson Jackson, the African-American caretaker of the White House animals, cheekily listed as Laddie Boy’s “valet.” Laddie Boy had many opinions to offer when asked: he believed Secretary of the Treasury Andrew Mellon ought to add a dog to at least one domination of U.S. paper money, and asked that Secretary of Commerce Herbert Hoover find measures to protect abandoned and homeless dogs. He joked Chihuahuas were ill-suited to the American climate, but then said seriously that they ought to be barred from being brought into the country. He was in favor of adding dogs to forestry teams and of training more police dogs to help with tracking bootleggers, as well as giving “a higher quality and larger quantity of rations” to malamutes and huskies employed in Alaska as mail-dogs. But he also felt that working dogs should only have eight-hour workdays, and appealed to the Secretary of Agriculture, Henry C. Wallace, to investigate what ingredients were going into dog food. Laddie Boy agreed with the idea that he acted as a sort of security guard for the President, and he took his duties seriously: “one in my position must be able to differentiate and to divide into classes visitors to the Chief.”[29] He had good opinions of several Cabinet members, even sparing a kind word for some of the female stenographers, who he said “always have a pleasant word to say as I pass.”[30]

The First Dog also had some reflections on how it felt to be in the public eye:

“…we of the White House very often have to sacrifice our own feelings in order that the public may be entertained and pleased. Not only must we participate in parades and different functions, but we must be photographed in company with this or that delegation of distinguished individuals. Some time ago I saw pictures of myself in three different sets of films. It really becomes tiresome after a while, but if the public demands the picture I suppose I will have to be patient.”[31]

The fanciful nature of the interview made most readers smile, but it also served a purpose. When asked more closely about the President, Laddie Boy painted a picture of an open-handed people-person who enjoyed the vast numbers of tourists at the Executive Mansion, and said that “he likes to be human, he likes sports, to mingle with his felow [sic] men, to go to the theater and to have jolly companions around him.”[32] This was the image Harding wanted the public to have of him, and Laddie Boy was a fantastic vehicle for the message. The idea of a talking dog was amusing, allowing Harding to use him “in a humorous way to strive for serious political goals.”[33]

Though Laddie Boy claimed he didn’t intend to give more interviews in the future, he continued to attract attention as a sort of news-hound (pun intended). He even “permitted” a letter he “wrote” to a show-dog named Tiger to be published in The National Magazine in 1922, promising Tiger a good time chasing squirrels on the White House lawn if he came to visit, but also making sure to extol President Harding’s virtues and to talk about the importance of loyalty and honesty — not things Harding found in some of his advisors.

Two whirlwind years at the White House came to an abrupt end when President Harding died while on a speaking tour in California. Laddie Boy’s grief made national headlines — there were even consoling poems written to the bereaved canine — though his warm reaction to incoming President, Calvin Coolidge, was noted for saddened readers.[34] Laddie Boy was sent to live with a Secret Service agent the Hardings had befriended, and he spent the rest of his years living in modest circumstances — however, when he died in 1929, his popularity was still such that he was given his own obituary in several national newspapers.[35]

Prior to Warren Harding’s death, newsboys across the country had donated 19,314 pennies to be made into a statue of Laddie Boy that would have been sent to the White House. Instead, the sculptor Bashka Paeff sent the final result to the Smithsonian Institute, where it was on display for many years.

Laddie Boy’s legacy also lives on in Rapid City’s City of Presidents: Warren Harding’s statue, on the corner of 9th and St. Joseph, has his faithful companion by his side. But most importantly, Laddie Boy has forever changed the way we perceived Presidential pets — we clamor for stories, watch videos about them, buy their books, and collect their memorabilia.

It’s a dog’s life, eh?

Footnotes

- ^ Brantz, Dorothee, Beastly Natures, (Charlottesville: The University of Virginia Press, 2010), 184.

- ^ “Millie’s Book,” Publisher’s Weekly, accessed August 15, 2018, https://www.publishersweekly.com/978-0-688-11913-3.

- ^ Peter Grier, “How Bo and Other ‘First Dogs’ Contribute to White House Easter Egg Roll,” Christian Science Monitor, April 8, 2012, https://www.csmonitor.com/USA/Politics/Decoder/2012/0408/How-Bo-and-other-first-dogs-contribute-to-White-House-Easter-Egg-Roll.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ “Top 10 Weird Exotic Pet Stories,” Animal Planet: Fatal Attractions, August 15, 2018, http://www.animalplanet.com/tv-shows/fatal-attractions/lists/9-president-gone-wild/.

- ^ Marguerite Roby, “Goody Goody Gumdrops,” Smithsonian Institution Archives, September 25, 2012, https://siarchives.si.edu/blog/goody-goody-gumdrops.

- ^ “Presidential Pets,” National Geographic Kids, accessed August 15, 2018, https://kids.nationalgeographic.com/explore/history/presidential-pets/#bo-white-house.jpg.

- ^ “Laddie Boy: Harding’s Popular Dog,” Dogs in History, June 29, 2017, http://dogs-in-history.blogspot.com/2017/06/laddie-boy-hardings-popular-dog.html.

- ^ Diane Tedeschi, “The White House’s First Celebrity Dog,” Smithsonian Magazine, January 22, 2009, https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/the-white-houses-first-celebrity-dog-48373830/.

- ^ Betsy Klein, “Trump Family Breaks with Presidential Pet Tradition,” CNN, October 21, 2017, https://www.cnn.com/2017/10/21/politics/donald-trump-presidential-pet/index.html.

- ^ “Top Dog at the White House,” History Engine, accessed August 16, 2018, https://historyengine.richmond.edu/episodes/view/5679.

- ^ “History of the White House News Photographers Association,” White House News Photographers Association, accessed August 13, 2018, https://www.whnpa.org/main/about/history-of-the-white-house-news-photographers-association/.

- ^ “’Dickie Boy’ in Trouble: “Laddie Boy’s” Brother Appear in Denver Court for Killing Chickens,” The New York Times, (New York City, NY), July 30, 1921.

- ^ “White House Kennels Filled; Coolidge Closes the Lists,” The New York Times, (New York City, NY), November 28, 1923.

- ^ “Who Proffered Laddie Boy as White House Guardian?,” The Fourth Estate, (New York City, NY) August 6, 1921.

- ^ Tedeschi, “First Celebrity Dog.”

- ^ “Sell Laddie Boy in Bronze – Mrs. Wilson’s Jewelry Firm Exhibits Statue of Harding Dog,” The New York Times, (New York City, NY), September 12, 1921.

- ^ “Laddie Boy to Lead Parade,” WashPo, 4-19-1921 “’Dickie Boy’ in Trouble: “Laddie Boy’s” Brother Appear in Denver Court for Killing Chickens,” The New York Times, (New York City, NY), July 30, 1921.

- ^ Lou Hebert, “Famous and Forgotten, Toledo’s Laddie Boy, The First Presidential Pet,” The Toledo Gazette, August 6, 2012, https://toledogazette.wordpress.com/2012/08/06/famous-and-forgotten-toledos-laddie-boy-the-first-presidential-pet/.

- ^ Truman, Margaret, White House Pets (Philadelphia: David McKay, 1969).

- ^ “Laddie Boy is Movie Star: Distinguished Dogs Cast to Support Him in Tuesday’s Show,” The Washington Post, (Washington, D.C.), May 1, 1921.

- ^ National Archives, “With Easter Monday You Get Egg Roll at the White House, Part 2: The First Children and Grandchildren,” Prologue Magazine Vol. 32, no. 1 (2000), https://www.archives.gov/publications/prologue/2000/spring/white-house-egg-roll-2.html.

- ^ Grier, “Bo and Other ‘First Dogs’.”

- ^ Annika Skoglund and David Redmalm, “’Doggy-biopolitics’: Governing via the First Dog,” SAGE Vol. 24, no. 2 (2017): 240-266, accessed August 15, 2018, http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1177/1350508416666938.

- ^ Helena Pycior, “The Making of the ‘First Dog’: President Warren G. Harding and Laddie Boy.” Society & Animals 13, no. 2 (2005): 109-138, http://www.animalsandsociety.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/01/pycior.pdf.

- ^ Caitlin Gibson, “The Crucial White House Position Trump Has Neglected to Fill: Five Good Reasons the President Should Get a Dog – And Soon,” The Washington Post, (Washington, D.C.), March 21, 2017.

- ^ “Harding Clears Desk: Several Hours of Morning Toil Follow an Auto Ride,” The Washington Post, (Washington, D.C.), March 7, 1921.

- ^ Major Tee, “Major Tee Secures First Real Interview with White House Pup, Laddie Boy,” The Evening Star, (Washington, D.C.), July 17, 1921.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Skoglund and Redmalm, “Doggy-biopolitics.”

- ^ “Laddie Boy’s Welcome Lucky, President Thinks,” The Washington Post, (Washington, D.C.), August 18, 1923.

- ^ “Laddie Boy, Pet of Harding, Dies: ‘First Dog of Land’ During Ohioan’s Administration Succumbs of Old Age,” The Washington Post, (Washington, D.C.), January 24, 1929.

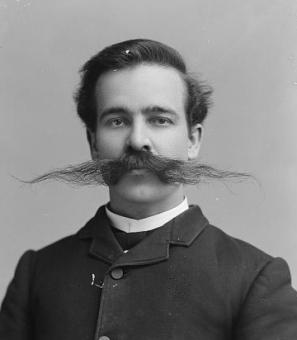

![John Philip Sousa, 6/8/23., 1923. [June 8] Photograph. https://www.loc.gov/item/2016835119/.](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/08831v.jpg?h=3792620a&itok=yW0Gbnyh)

![Sketch of the mythical fuan by Pearson Scott Foresman. [Source: Wikipedia]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2023-10/Goatman_Wikipedia_Faun_2_%28PSF%29.png?h=64a074ff&itok=C9Qh-PE1)