When the Willard Hotel Served as the White House

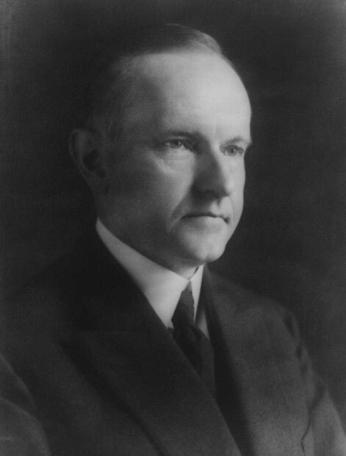

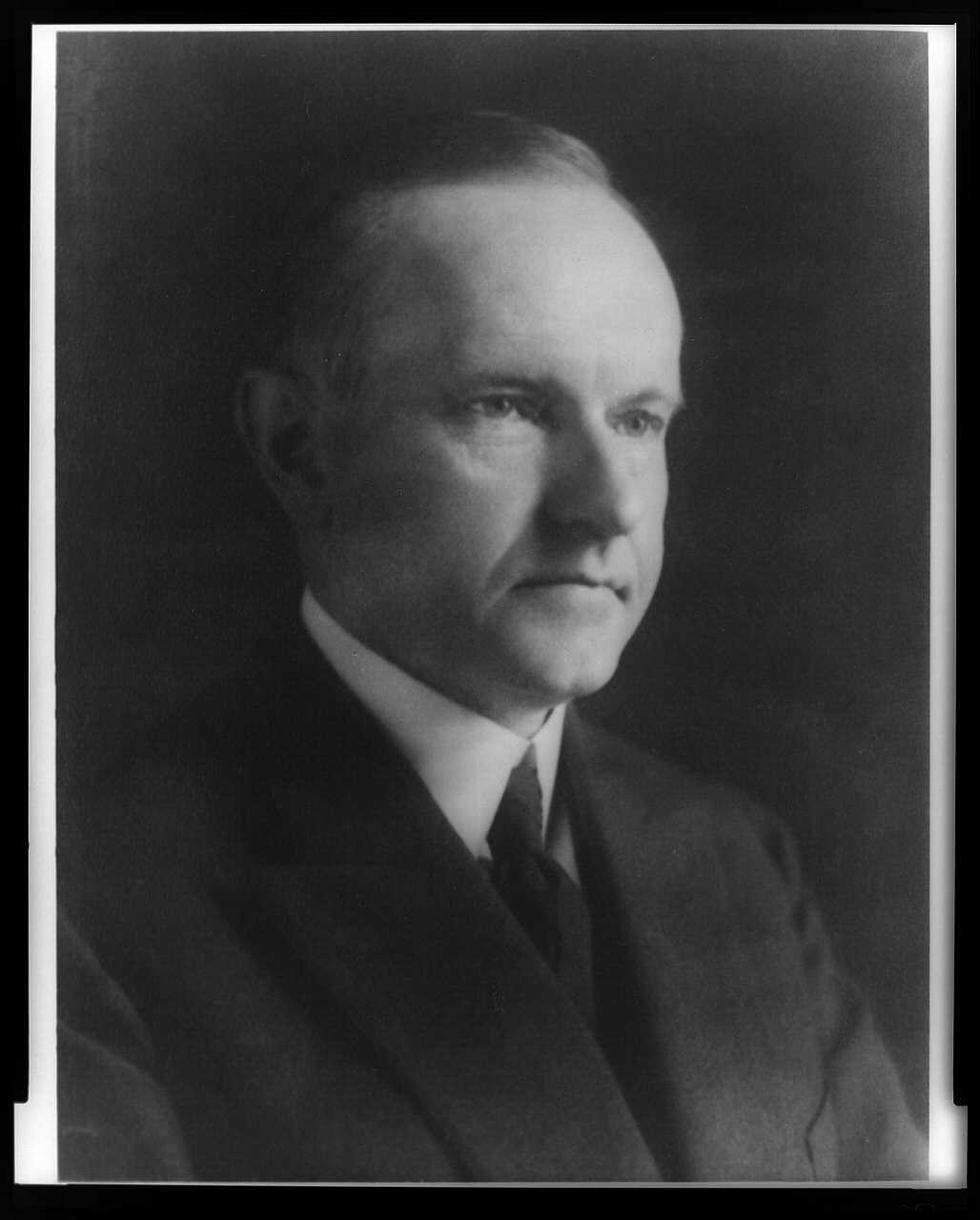

Calvin Coolidge was born in rural Vermont in 1872, and he studied law through two apprenticeships before being admitted to the bar when he was 25.[1] He worked his way up the New England political ladder in the early 20th century and then became a national political figure. Coolidge was elected Vice President in 1920 and became President three years later. Throughout his life, the 30th President was known to be a frugal man.

“There is no dignity quite so impressive, and no independence quite so important, as living within your means,”[2] Coolidge said.

Coolidge practiced what he preached and during his career in politics; he lived rather simply, renting half of a duplex in Northampton, MA for almost 25 years.

“When he was elected lieutenant governor of Massachusetts, Mr. Coolidge’s papers and addresses will ampton [sic] for one room in the Adams House, Boston. His elevation to the governorship found his family still occupying half of the unpretentious frame building in Northampton. As for the governor, he simply took an additional room in the Adams house,”[3] The Washington Post wrote.

This frugality continued when he came to Washington.

When he was elected Vice President, Coolidge followed in the footsteps of several other Vice Presidents before him and he chose to stay at the Willard Hotel in Washington, D.C., rather than buy a house. (Vice Presidents were responsible for finding their own place to live until the Naval Observatory became the Official Residence in 1974, but Walter Mondale was the first to move in three years later.[4])

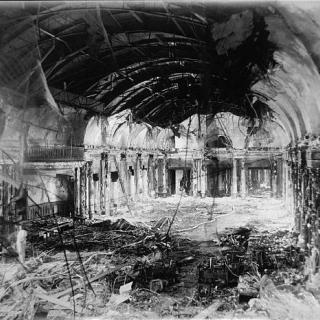

In 1921, Coolidge took over a third floor suite from outgoing Vice President Thomas Marshall. Coolidge paid $8 per night for the accommodations.[5] He would remain there until August 23, 1922 when a fire broke out in the Willard. Coolidge and his wife, Grace, along with President Warren Harding’s personal doctor Charles E. Sawyer (who was also at the Willard the day of the fire), stayed at the White House for a few months while the damage was repaired. But then, it was back to the Willard.

On August 2, 1923, Coolidge was on vacation at his family home in Vermont when Harding died in California after a cross country trip. Coolidge took the oath of office in the early hours of the morning on August 3,[6] and then returned to Washington.[7]

For the next few weeks while Harding’s family moved out, the Willard would become the White House. To signify that the Chief Executive lived there, the Presidential Flag flew outside the hotel.[8]

One of Coolidge’s first acts as president in his temporary White House was to take the oath of office again. Coolidge’s father, a notary in Vermont, had given Coolidge the oath on August 3, but Solicitor General James Beck determined a state official couldn’t swear a federal official into office. So, Supreme Court of the District of Columbia Associate Justice A.A. Hoehling gave Coolidge a second oath at the Willard.[9]

After Harding’s unexpected death, it stands to reason that Coolidge couldn’t live at the White House immediately, but surely he could go to work in the West Wing, right? Well, no. The executive offices at the White House were undergoing renovations at the time, so Coolidge prepared to commute from the Willard to the U.S. Capitol where, as Vice President, he had an office as the President of the Senate.[10]

As The Post reported on August 4, “He will go there this morning at 9 o’clock to give attention to passing matters of state and then will return to the Willard where, it is understood, he will confer with the Secretary of State and other cabinet members who may be in Washington.”[11]

Coolidge’s plan didn’t last long as it turned out. The very next day, the paper’s front-page headline announced: “Executive Abandons Plan to Retain Former Capitol Office and Sets Up Temporary Establishment at Hotel.”[12]

The article laid out the specifics:

“Abandoning his first contemplated plan to establish offices in his former rooms at the Capitol, the new President promptly decided that it would be better to set up a temporary White House close by his own suite in the Willard Hotel. Before the morning hours were well on their way, five rooms on the third floor of the hotel had been converted into offices and a force of clerks and stenographers were busily engaged dispatching the work of the chief executive.”[13]

For the next two weeks, President Coolidge conducted business from the Willard with the sort of busy schedule one would expect. For example, on August 6, The Post reported that Coolidge had lunch with W.M. Butler (a member of the Republican National Committee from Massachusetts), met with Republican Senator Frank Brandegee from Connecticut for two hours, saw DC Supreme Court Justice Wendell Phillips Stafford, and discussed plans for Harding’s funeral with Secretary of State Charles Hughes[14] — all from the third floor of the hotel.

Following Harding’s funeral on August 10,[15] the Coolidges appeared to be in no rush to move into the White House. The Post reported that Florence Harding planned to stay in the White House until her family’s belongings could be moved out, and Grace Coolidge reportedly told Florence, “the White House was hers as long as she wished to remain there.”[16]

On August 21, the Coolidges finally moved into the White House,[17] but they wouldn’t stay there for the entirety of his time in office. Just months after they moved in, The New York Times reported that “the White House has been declared unsafe” and Chief of Engineers of the Army, Major General Lansing Beach asked Congress for $400,000 to conduct the necessary repairs. “A preliminary study of the situation in the interior upper portion of the Executive Mansion has indicated a condition which renders the building unsafe, both from the standpoint of security in the structural feature and the fire hazard present,”[18] Beach said.

Despite Beach’s concerns that the building was in immediate danger, Coolidge waited until 1927 to conduct the repairs, which included fixing the leaky roof and expanding the attic space into a full third story of the building.[19] While the repairs were underway, the Coolidges lived at Patterson House, a Dupont Circle mansion owned by Cissy Patterson.[20]

After his time in office, Coolidge retired to Massachusetts, where he finally bought a house — somewhat reluctantly, it seems. As the New York Times reported in 1933, “He moved back into the two-family house in Northampton and resumed his favorite relaxation of porch sitting, but found the streets jammed with tourists who came to stare at him. In self-protection he was forced to buy a house and eight acres in another part of Northampton for $40,000.”[21]

Footnotes

- ^ William Bushong, “The Life and Presidency of Calvin Coolidge,” The White House Historical Association, https://www.whitehousehistory.org/the-life-and-presidency-of-calvin-coo….

- ^ “U.S. Senate: Calvin Coolidge, 29th Vice President (1921-1923),” www.senate.gov, https://www.senate.gov/about/officers-staff/vice-president/VP_Calvin_Co….

- ^ “Plain Living and High Thinking a Boast of Coolidge Since Early Public Life,” The Washington Post, August 3, 1923.

- ^ “The Vice President’s Residence & Office,” The White House (The White House, 2017), https://www.whitehouse.gov/about-the-white-house/the-vice-presidents-re….

- ^ “U.S. Senate: Calvin Coolidge, 29th Vice President (1921-1923),” www.senate.gov.

- ^ “Calvin Coolidge,” The White House (The White House, 2017), https://www.whitehouse.gov/about-the-white-house/presidents/calvin-cool….

- ^ Harry N. Price, “Hughes, New and Sherrill Greet New Executive and Escort Him to Temporary Home at Willard,” The Washington Post, August 4, 1923.

- ^ “Willard Hotel Marks 20 Years Since Reopening,” NPR.org, January 15, 2006, https://www.npr.org/templates/story/story.php?storyId=5158557.

- ^ “Coolidge’s Two Oaths of Office | Forbes Library,” Forbes Library, August 3, 2009, https://forbeslibrary.org/blog/2009/08/03/coolidges-two-oaths-of-office/.

- ^ Harry N. Price, “Hughes, New and Sherrill Greet New Executive and Escort Him to Temporary Home at Willard”

- ^ Harry N. Price, “Hughes, New and Sherrill Greet New Executive and Escort Him to Temporary Home at Willard”

- ^ Harry N. Price, “Executive Abandons Plan to Retain Former Capitol Office and Sets Up Temporary Establishment at Hotel,” The Washington Post, August 5, 1923.

- ^ Harry N. Price, “Executive Abandons Plan to Retain Former Capitol Office and Sets Up Temporary Establishment at Hotel”

- ^ “Hour by Hour Sunday Of President Coolidge,” The Washington Post, August 6, 1923.

- ^ “Warren G. Harding Funeral,” White House Historical Association, https://www.whitehousehistory.org/warren-g-harding-funeral.

- ^ “Mrs. Harding Bravely Faces Task of Breaking Up Home,” The Washington Post, August 12, 1923.

- ^ “On Threshold of New Home,” The Washington Post, August 22, 1923.

- ^ “White House Unsafe; Needs $400,000 Repairs,” timesmachine.nytimes.com (The New York Times, December 4, 1923), https://timesmachine.nytimes.com/timesmachine/1923/12/04/106023805.pdf?….

- ^ “TR Renovation - White House Museum,” www.whitehousemuseum.org, http://www.whitehousemuseum.org/special/renovation-1927.htm.

- ^ Marjorie Hunter, “OF SURROGATE WHITE HOUSES,” The New York Times, December 27, 1984, sec. U.S., https://www.nytimes.com/1984/12/27/us/of-surrogate-white-houses.html.

- ^ “Unusual Political Career of Calvin Coolidge, Never Defeated for an Office,” archive.nytimes.com, January 6, 1933, https://archive.nytimes.com/www.nytimes.com/learning/general/onthisday/….

![Sketch of the mythical fuan by Pearson Scott Foresman. [Source: Wikipedia]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2023-10/Goatman_Wikipedia_Faun_2_%28PSF%29.png?h=64a074ff&itok=C9Qh-PE1)