Hugh Bennett and the Perfect Storm: When the Dust Bowl Came to Washington

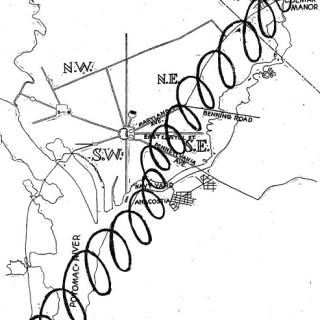

Washington in 1935, darkening the skies over the

Lincoln Memorial. (Source: USDA website)

It was March 21, 1935, and Hugh Bennett was running out of time. In June, the Soil Erosion Service would run out of temporary funding for field work and demonstration projects. Yet so much work remained to be done. The Dust Bowl was in full swing. Drought, loose soil and wind storms were ravaging the Midwest and – quite literally – piling on to struggling farmers and ranchers already beaten down by the Great Depression. But in Washington, the future of the SES was caught up in political wrangling between the Department of the Interior, the USDA, and the bureaucrats who ran the multitude of work relief agencies of the New Deal era. President Roosevelt and Congress were also involved, as each presented ideas on how the nation’s soil should be managed.

As the director of the Soil Erosion Service, Bennett had been asked to deliver testimony to a congressional subcommittee on H.R. 7054, a new bill that would create a singular and permanent national soil conservation service under the jurisdiction of the USDA. The empowerment of one responsive agency with permanent funding was a big opportunity. Up to this point, soil erosion as an issue that had been looked at disjointedly, and only recently by the SES, the USDA, the Bureau of Chemistry and Soils, the Bureau of Agricultural Engineering, and the Forest Service, among others. If the powers that be could agree on a management structure, it would mean that Bennett’s years of work combating soil erosion were finally paying off. More importantly, it would mean that his agency could continue its work helping struggling Americans.

But Bennett’s testimony was running on and on, spilling over from his original appointment the day before, and was even eliciting a few polite yawns from members of the committee. He needed something big to drive home his point… and he had a plan.

If ever there was a man who knew the nation’s soil, it was Hugh Bennett. After growing up on a North Carolina cotton farm, he had spent most of his professional career working for the U.S. Bureau of Soils at the Department of Agriculture as a field researcher. Through his surveys across the states and in other countries he had come to the conclusion that ‘soil wastage’ was a serious threat to the U.S. He became a strong a proponent of re-evaluating nationwide farming and tilling practices to prevent erosion.

However, efforts to enact change had gone largely ignored in the previous decades of prosperity. In 1909, Chief of the Bureau of Soils, Professor Milton Whitney, echoed the sentiment of many in those days, asserting that the nation’s soil was of “an inexhaustible and permanent fertility.” Such an attitude persisted into the 1920s and, after the economic crash of 1929, most people were more focused on putting food on the table than discussing soil erosion. It wasn’t until 1933 that the government took serious action, creating the Soil Erosion Service (with Bennett as the director) and granting funding until June 1935.

By the spring of 1935, the future of the SES was in question. Funding was about to run out, and the USDA wanted to absorb the agency. Secretary of the Interior, Harold Ickes, had an alternative vision of a new Department of Conservation that would eventually deal with issues of the soil. So, just two years after its creation, the SES was the object of a Beltway tug-o-war.

Bennett hoped his plan would spur a resolution. Prior to giving his testimony on March 21, he received word from assistants in the Midwest that a large dust storm, the same sort that would define the second half of the Great Depression, was moving towards the East Coast and would pass over Washington, D.C. If he could time his testimony correctly with the incoming storm, then Congress might be convinced to cut through the red tape.

As Bennett was finishing his remarks, the storm that he had been told was moving east descended on Washington. When the sky went dark outside the windows of the hearing, one member of the committee reportedly noted,

“It is getting dark. Perhaps a rainstorm is brewing.”

“Perhaps it is dust,” another ventured.

“I think you are correct,” Bennett agreed. “It does look like dust.”

Willington Brink provides a dramatic look at how the scene played out in his 1950 biography of Bennett, Big Hugh: The Father of Soil Conservation.

The group gathered at a window. The dust storm for which Hugh Bennett had been waiting rolled in like a vast steel-town pall, thick and repulsive. The skies took on a copper color. The sun went into hiding. The air became heavy with grit. Government's most spectacular showman had laid the stage well. All day, step by step, he had built his drama, paced it slowly, risked possible failure with his interminable reports, while he prayed for Nature to hurry up a proper denouement. For once, Nature cooperated generously.

Less than a month later, another terrible storm struck the Midwest on April 14, giving that day the name “Black Sunday” and causing a Washington journalist the coin the term “Dust Bowl.” Between Bennett’s sub-committee stunt and the events of Black Sunday, Congress was finally inspired to act on the issues of erosion. The very next day the Senate passed H.R. 7054. FDR signed the Soil Conservation and Domestic Allotment Act of 1935 on April 27. The SES was reorganized under the USDA as the Soil Conservation Service and given permanent funding, guaranteeing the future of the soil conservation program.

With a big assist from Mother Nature, Hugh Bennett’s dream had come true.

Sources:

Cook, Maurice G. “Hugh Hammond Bennett: The Father of Soil Conservation” North Carolina State University, (Link)

“DC Invaded by Dust Storms from the Midwest” Washington Post, March 22, 1935.

“Hugh Hammond Bennett” from ‘Surviving the Dust Bowl’ on American Experience. (Link)

Bennett, H.H. “Capital, Caught by Dust Storm, Turns to West’s Topsoil Problem” Washington Post, March 10, 1935.

Helms, Douglas. “Hugh Hammond Bennett and the Creation of the Soil Conservation Service,” USDA. (Link)

![Sketch of the mythical fuan by Pearson Scott Foresman. [Source: Wikipedia]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2023-10/Goatman_Wikipedia_Faun_2_%28PSF%29.png?h=64a074ff&itok=C9Qh-PE1)