Hostage Standoff at the D.C. Jail, October 11, 1972

In the wee hours of the morning on October 11, 1972 William Claiborne was doing what most other Washingtonians were doing: sleeping. When the phone rang at 4:15 am, he answered groggily. A panicked voice on the other end of the line said that inmates at the D.C. Jail were holding guards hostage and had requested his presence.

A few minutes later, Corrections Director Kenneth L. Hardy called with a personal plea. “Mr. Claiborne, they have taken Cellblock 1 and they are holding nine of my men as hostages. They want to talk to you. Can you come down here?"[1] The captors, Hardy explained, wanted Claiborne to participate in the negotiation.

As a reporter for The Washington Post, Claiborne’s normal beat included covering D.C.’s troubled correctional system, and related events including the bloody prison riot at Attica in 1971. He was accustomed to racing after the story.

However, this was something different altogether. Hand-picked by inmates to negotiate the standoff with corrections officials, Claiborne wasn’t reporting the news – he was at the center of it. Not that he had much time to consider the role reversal. Within 10 minutes, a police squad car pulled up in front of his home in Northwest. He hopped inside and the car took off for the jail, lights flashing and sirens blaring.

When he got there, Hardy shared the details about what had transpired. Between 1 and 2 am, an inmate in Cellblock 1 pretended to have a seizure. When two correctional officers came to check on him, the cellmate produced a loaded .38 pistol and subdued the two guards. They freed 50 other inmates and took control of the cellblock, capturing several other guards as hostages in the process.

Claiborne agreed to go inside the jail with Hardy. As he described in the next day’s Post, “We walked to a steel door off the visitors’ rotunda that rises to the full four-story height of the jail. We then entered a small alcove and the steel door shut behind us. There we faced another steel door with a small peephole, through which we could see a number of inmates. One held a snubnosed revolver to the guard’s head.”[2]

Addressing Claiborne through the peephole, one of the inmates said, “We want you to understand one thing very clearly. This is not a riot, it’s a revolution.”[3] The inmates then pulled the reporter inside and frisked him for weapons. Hardy was brought in next.

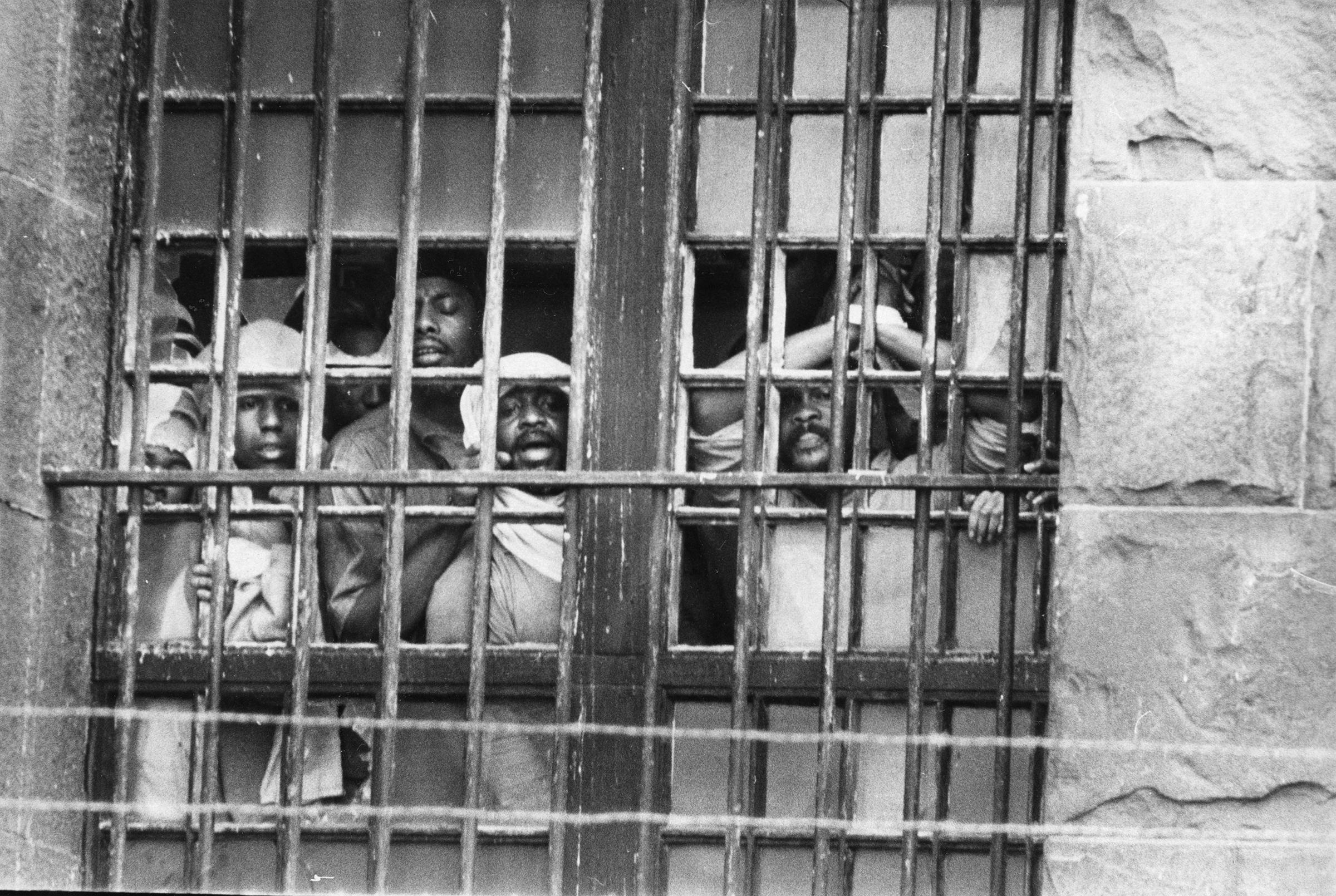

The inmates, according to Claiborne, “desperately tried to convince me of their single mindness of purpose.”[4] They weren’t interested in bargaining for better conditions inside the notoriously overcrowded 100-year old facility. They wanted to be released. Immediately. In the words of one, “We’re treated like animals, and we want out.”[5]

After about 35 minutes, Claiborne was sent back outside to carry the message to officials. Meanwhile, Hardy was kept as a hostage in the cellblock.

For the next seven hours, inmates repeatedly summoned Claiborne to the jail windows and reiterated their demand for freedom. He passed the demands on to a growing cadre of corrections officials and negotiators, which included New York Congresswoman Shirley Chisholm, D.C. delegate Walter Fauntroy, D.C. school board president Marion Barry, Petey Greene, and others.

The inmates stuck to their demands to be released.

“We don’t want nothing’ but the sidewalk. What do you think we want, better food? Bull___. We want the sidewalk, man.”

“We’re dead now, we’re better dying out there than in here. We don’t give a ___.”

“We ain’t bitches, man. We don’t mind dying for the ____ cause.”[6]

Throughout the morning and early afternoon, the standoff grew more and more tense. At one point the captors put Hardy in front of the window and held what appeared to be a knife to his head. The Corrections Director pleaded with police not to send the Civil Disturbance Unit to quell the uprising, saying, “I don’t want any bloodshed.” Shortly thereafter, an inmate shouted a warning about what would happen if police decided to storm the jail, anyway. “His head is coming off, you better believe that.”[7] At another point, the captors hung the bloody shirt of a guard, who had been injured in the takeover, from the window.

Later in the afternoon, Clairborne stepped back and Chisholm took charge of the negotiations. As she told reporters later, “I was there to see if I could break the situation because we had nine men’s lives at stake and that was the overriding thing in my mind constantly. These men, desperate as they are, are not going to release hostages willy-nilly. You have to negotiate and bargain and plead. They say they are willing to die. You see, these men don’t care about life any more but in the process of being willing to die they may take others with them.”[8]

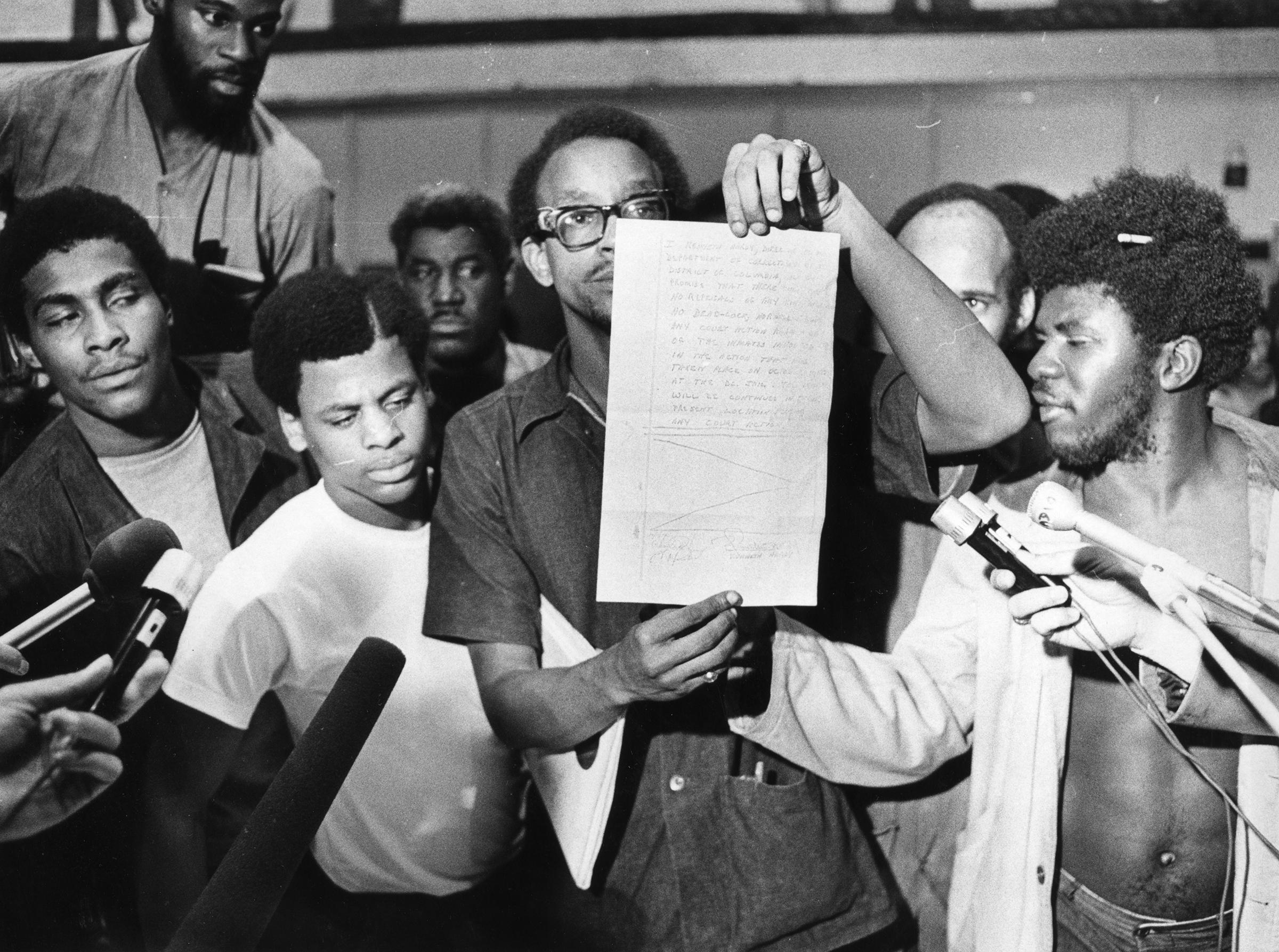

Thankfully, negotiators led by Chisholm – who had experience with previous prison standoffs in New York – were successful in ratcheting back the tension. Eventually backing off their demands for release, the inmates agreed that they would release the hostages in exchange for the opportunity to go before a federal judge to air their grievances about the jail, and the promise of no reprisals for their actions.

U.S. District Judge William J. Bryant held an emergency hearing that evening, which lasted past midnight. Six inmate representatives, along with Kenneth Hardy, D.C. Delegate Walter Fauntroy and a few others were bussed to the courthouse. One by one, the inmates went before the judge and lambasted the conditions at the jail, a facility that had been built in the 1870s and was bursting at the seams with overcrowding and physical plant issues.

Many of the problems were well known. Months prior to the uprising, the ACLU had issued a scathing – if also controversial – report that excoriated the unsanitary living conditions, lack of medical care and brutality at the jail, which it called a “filthy example of man’s inhumanity to man.”[9]

Amidst the long list of complaints, however, one stood out. Several inmates took aim at the Department of Corrections’ policy of housing teenage offenders with hardened adult criminals.[10] As inmate Albert McCoy told the judge,

“You take a 16-year-old kid and stick him in there with someone who’s been in Leavenworth or Atlanta for 30 or 40 years and it ruins the kid.”[11]

This policy had grown out of the Nixon administration’s District of Columbia Court Reform and Criminal Procedure Act of 1970. More commonly known as the “D.C. Crime Bill,” the legislation was an attempt to make Washington, D.C. “a model of law observance and enforcement.” Amongst other provisions, it granted new powers to police and stipulated that juveniles 16 or older be tried as adults if they were charged with certain felonies.

Hardy shared the concern about what impact such classifications might have on young offenders, telling Bryant, “there must be a massive input for the courts… much more sensitivity.” However, he also pointed out that the D.C. penal system was “facing a population explosion,” which left him with limited options.[12]

Finally, shortly after midnight, the ordeal came to an end. Judge Bryant ordered the separation of juveniles from the adults at the D.C. jail. He also ordered that the public defender service immediately make lawyers available to all of the inmates who wanted them. Back at the jail, hostages were released when inmates were read a note signed by Hardy promising “no reprisals of any kind (or) court action against any inmate.”[13]

Twenty-two hours after it began, the harrowing episode was over but the issue of penal reform in Washington – and the nation as a whole, for that matter – was far from settled. As The Washington Post noted, “Washington’s troubled prisons, like so many across the country, are caught in the deepening conflict between prisoners’ demands for change and mounting community alarm over the spread of crime.”[14]

Settling back into his more familiar role as a reporter, William Claiborne continued to cover these issues for the Post through the mid 1970s. In 1973, jurors for the Pulitzer Prize unanimously recommended that he win the Local Reporting award “for his enterprising, incisive and courageous reporting of the prison situation in the District of Columbia,” noting that “the members of the jury feel strongly that his work represents the high ideas of the Pulitzer Prize history.”[15] It was one of three Pulitzers the jurors recommended for the Post that year.

Unfortunately for Claiborne, the Pulitzer advisory board – a body which outranks the jury – later decided to give the Post an additional award for its Watergate reporting. Since four Pulitzers for one publication was unprecedented at the time, the award that would’ve gone to Claiborne was withdrawn.[16]

Postscript

Despite Kenneth Hardy’s note promising no reprisals in exchange for the safe release of the hostages, nine inmates who participated in the uprising were prosecuted and convicted on various charges. The courts determined that Hardy’s note was coerced under the threat of violence and, thus, invalid.[17]

The old D.C. Jail building was replaced by a new facility next door in 1976. The old building was subsequently torn down and some of the stones were used to repair the Smithsonian Castle.[18]

See more photos of the 1972 hostage crisis at the jail on the Washington Area Spark Flickr account.

Footnotes

- ^ Claiborne, William L. “They Led Me Into a Hall, Saying, ‘Don’t Hurt Him’: Reporter Acted as Go-Between For Prisoners, D.C. Officials.” The Washington Post, Times Herald (1959-1973); Washington, D.C. October 12, 1972.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ “D.C. Jail Inmates Hold 9 Guards and Hardy.” Evening Star, October 11, 1972.

- ^ Claiborne, William L. “They Led Me Into a Hall, Saying, ‘Don’t Hurt Him’: Reporter Acted as Go-Between For Prisoners, D.C. Officials.” The Washington Post, Times Herald (1959-1973); Washington, D.C. October 12, 1972.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Crawford, Clare. “Mrs. Chisholm ‘Took Charge’”, Evening Star, October 12, 1972.

- ^ Claiborne, William L. “ACLU Probe Took 2 Years: ACLU Study Cites Filth, Inhumanity at D.C. Jail.” The Washington Post, Times Herald (1959-1973); Washington, D.C. January 28, 1972, sec. METRO Obituaries Weather.

- ^ Kuhn, Mary Ann. “Plight of Jail Told in Court,” Evening Star, October 12, 1972: B6.

- ^ Johnson, Haynes. “Jail Rebels Free All Hostages: Prisoners Release Hostages After Airing Grievances to Judge.” The Washington Post, Times Herald (1959-1973); Washington, D.C. October 12, 1972.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Osnos, Peter. “Pressures Build On Prisons in Time of Change.” The Washington Post, Times Herald (1959-1973); Washington, D.C. October 12, 1972.

- ^ Fischer, Heinz-D., and Erika J. Fischer. Complete Historical Handbook of the Pulitzer Prize System 1917-2000: Decision-Making Processes in All Award Categories Based on Unpublished Sources. Walter de Gruyter, 2011: 105.

- ^ “Washington Post Journalist William Claiborne Traveled the World to Tell Its Stories.” Washington Post. Accessed October 12, 2018. https://www.washingtonpost.com/local/obituaries/washington-post-journalist-william-claiborne-traveled-the-globe-to-tell-its-stories/2013/03/03/f66fe56a-5b50-11e2-9fa9-5fbdc9530eb9_story.html.

- ^ “Washington Post Journalist William Claiborne Traveled the World to Tell Its Stories.” Washington Post. Accessed October 12, 2018. https://www.washingtonpost.com/local/obituaries/washington-post-journalist-william-claiborne-traveled-the-globe-to-tell-its-stories/2013/03/03/f66fe56a-5b50-11e2-9fa9-5fbdc9530eb9_story.html.

- ^ “The Hill Is Home | Lost Capitol Hill: The DC Jail | The Hill Is Home.” Accessed October 12, 2018. https://thehillishome.com/2010/06/lost-capitol-hill-the-dc-jail/.

![Sketch of the mythical fuan by Pearson Scott Foresman. [Source: Wikipedia]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2023-10/Goatman_Wikipedia_Faun_2_%28PSF%29.png?h=64a074ff&itok=C9Qh-PE1)