Christmas Escape at Lorton, 1974

It was Christmas night 1974 in Lorton Reformatory’s Maximum Security wing. Correctional Officer Lt. O.W. Larsen was keeping watch over the mess hall where around 100 inmates were finishing dinner and sitting down for a showing of “The Hong Kong Connection,” a Kung Fu movie. Suddenly Larsen felt the muzzle of a handgun pressed into his neck. Earl Coleman, serving 5 to 15 years for robbery and nicknamed “Killer,” had his finger on the trigger. As Coleman overpowered Larsen, other inmates did the same to the other guards in the hall. Within moments they had control of the room.

Three guards were told to take off their uniforms while Larsen was forced to phone Tower 6 and inform the guard on duty there that relief was on the way. Eight inmates, including three dressed in the guard uniforms, then headed for the tower. Officer Timothy Brown was forced to accompany them.

As the Washington Post detailed later:

To get to the tower, one must pass through three electrically controlled gates to the outside of the complex itself. Two gates must be closed for the third to operate. The tower officer, recognizing Brown, let him and a disguised inmate pass through; the other six men remained concealed in the darkness.[1]

Unaware of the plot that was unfolding on the ground, the guard at the top of Tower 6 threw the keys down to Brown. He and his captor then climbed to the top, where the disguised inmate took control of the tower. He opened the gates in succession to allow three more inmates to escape before taking several guns and leading the guards back down from the tower. Once at the bottom, the four escapees demanded the keys to Officer Brown’s car, an orange Volkswagon beetle, which was parked in a nearby lot.

Coleman, Tyrone Nobles, Clifton Bullock and Ronald Tibbs raced away from the prison as the alarms sounded. A guard stationed in Tower 5 fired at the car and, it was determined later, struck Tibbs, who was killed.

A few miles up the road near Lincolnia, the surviving escapees ditched the VW and looked for another vehicle. Seeing a man getting into his car, they approached and showed their weapons. The trio forced the motorist to drive them into the District where they got out and – thankfully – let him return home unharmed.

Back at the prison, the situation was deteriorating quickly. Men were angry and some claimed that by closing the gates prematurely, the four men who escaped had double-crossed a much larger group that was planning to escape.[2]

In the mess hall, inmates held nine guards – including Officer Larsen – and a steward from the kitchen as hostages. Lorton officials scrambled to respond as the inmates expressed grievances. Complaints ranged from the day-to-day conditions in the prison to concerns about the criminal justice system itself.[3] Of particular concern was the prison system’s practice of transferring inmates from Lorton to other institutions, many of which were far away from Washington and difficult for family members to visit.

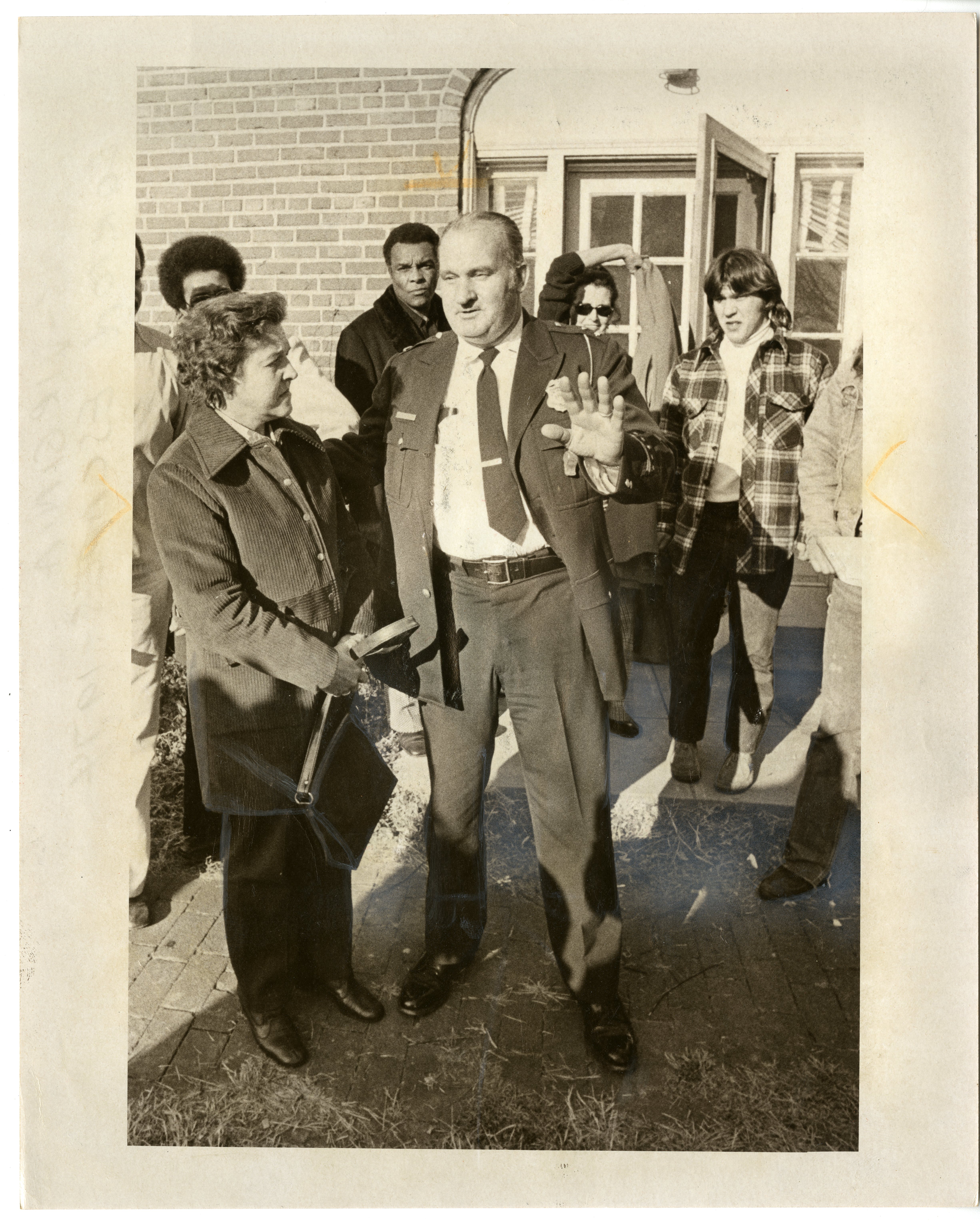

Negotiations began, first over the phone and then face-to-face as a small group of inmate leaders met with D.C. Corrections Department Director Delbert Jackson. Concerned that the prison officials would not follow through on negotiated terms, inmates requested that members of the media be allowed inside the prison to observe the discussions.

As the evening stretched into the wee hours, families of inmates and guards gathered at Lorton, both sides fearful of what might happen in the mess hall should the negotiations turn south. It was a tense scene to say the least. As Officer Larsen’s daughter told the Washington Star-News, “When [the inmates’ families] found out my father was a hostage, they told me, ‘If your father is over there, you’d better start praying.’”[4]

Around 11 pm, the inmates released one of the guards, Rogers Lee Porter, “as a good faith gesture.”[5] In return, Jackson agreed to allow some family members into the mess hall. Outside the prison, a fleet of heavily armed officers from the Fairfax County Police, Virginia State Police and the FBI kept a tight ring around the prison.

Discussions continued overnight. According to the Star, which had a reporter inside, it was a charged atmosphere:

A bad joke or an exaggerated demand by one of the prisoners would provoke nervous giggling that would erupt in an explosion of laughter. Just as suddenly, it would die, leaving only the sound of the prisoners’ tense voices listing their demands.[6]

19 hours after the standoff began, the two sides finally reached an agreement. It called for changes in visiting procedures, increased medical services, new educational opportunities for inmates, and adjustments to other day-to-day policies.

Inmates also secured – in the form of a handwritten note signed by Roy Gerard, Acting Director of the Federal Bureau of Prisons – a promise that those who had participated in the uprising would not be transferred to other prisons.[7] Jackson further promised that he would not seek reprisals against those involved.

With an agreement in place, the inmates released the remaining officers. The Christmas standoff was over with no additional casualties.

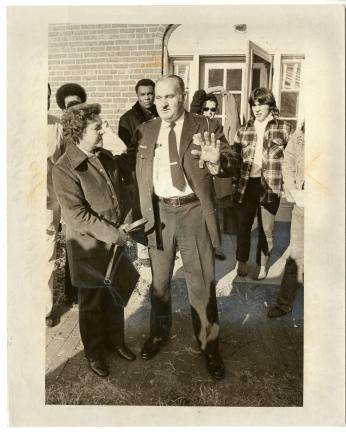

As he reunited with his family, Officer Larsen described the experience as “touch and go” and “a desperate situation” brought on by “desperate men,” but said that the inmates “treated us all right.”[8]

Inmate spokesman Thomas Reed described the siege as a response to the conditions at Lorton:

“It all stemmed from dehumanized conditions in maximum security. We have to change these conditions for brothers like myself who have life.”[9]

Meanwhile, a relieved Delbert Jackson focused on the positives:

“We were able to sit down with fellow human beings—that’s what they are, you know, a lot of people think they’re animals but they’re really human beings—we were able to sit down and negotiate with both sides trying hard to reach some agreement.”[10]

Thank goodness.

Epilogue

The three surviving escapees managed to evade authorities for several weeks before they were recaptured in the District in February 1975. Despite Delbert Jackson’s pledge not to seek reprisals against the inmates that participated in the uprising, acting U.S. Attorney for the Eastern District of Virginia David Hopkins ultimately did decide to prosecute, and nine inmates were indicted for their roles in the siege. As Hopkins told the Star, “It is difficult for me to conceive of an uprising where no crime was committed.”[11]

Footnotes

- ^ Feaver, Douglas B., and Judy Luce Mann. “3 Prisoners Still Sought; One Killed: 80 Lorton Inmates End Rebellion, Free 7 Hostages.” The Washington Post (1974-Current File); Washington, D.C. December 27, 1974.

- ^ “2 of 9 Lorton Hostages Freed; Convicts’ Demand Prolongs Siege.” Evening Star, December 26, 1974.

- ^ Byrd, Earl and Robert Pear. “‘I Was Almost Out, But I Returned for Brothers.’” Evening Star, December 26, 1974.

- ^ Byrd, Earl and Robert Pear. “‘I Was Almost Out, But I Returned for Brothers.’” Evening Star, December 26, 1974.

- ^ “2 of 9 Lorton Hostages Freed; Convicts’ Demand Prolongs Siege.” Evening Star, December 26, 1974.

- ^ Boyd, Earl. “Inside, Men Are Left With a ‘Trust Me.’” Evening Star, December 27, 1974.

- ^ “Lorton Hostages Free, Siege Ends.” Evening Star, December 26, 1974.

- ^ Kelly, Brian, and Mary Margaret Green. “Outside, the Siege Ends In Smiles and Tears, As...” Evening Star, December 27, 1974.

- ^ Boyd, Earl. “Inside, Men Are Left With a ‘Trust Me.’” Evening Star, December 27, 1974.

- ^ Feaver, Douglas B., and Judy Luce Mann. “3 Prisoners Still Sought; One Killed: 80 Lorton Inmates End Rebellion, Free 7 Hostages.” The Washington Post (1974-Current File); Washington, D.C. December 27, 1974.

- ^ Love, Thomas. “Lorton Rebels Face Penalties.” Evening Star, December 28, 1974. See also Kiernan, Laura A. “9 Inmates Indicted in Lorton Melee.” The Washington Post (1974-Current File); Washington, D.C. March 4, 1975, sec. GENERAL.

![Sketch of the mythical fuan by Pearson Scott Foresman. [Source: Wikipedia]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2023-10/Goatman_Wikipedia_Faun_2_%28PSF%29.png?h=64a074ff&itok=C9Qh-PE1)