L'Enfant's Guide to Getting Fired

It takes a lot of talent to design a city, especially one with such sweeping vistas and wide, radial streets as our Nation’s Capital. It’s hard not to admire the vision of Major Pierre Charles L’Enfant, the engineer behind Washington, D.C. But everybody makes mistakes—even visionaries— and L’Enfant was certainly no exception.

His biggest blunder was probably tearing down the house of his boss’s nephew.

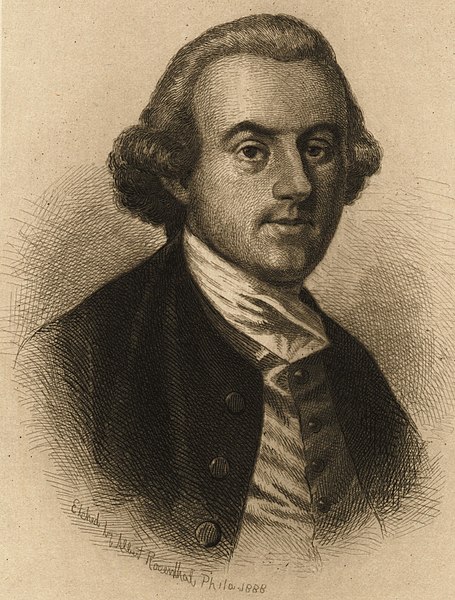

Now, when we say “boss,” we’re not talking about George Washington. It’s true that the founding father hand-picked L’Enfant to design the Federal City, but he also hired three Commissioners; Thomas Johnson, David Stuart, and Daniel Carroll; to oversee the new Capital.[1] L’Enfant was answerable to these men, although he clearly didn’t see it that way.

In the first months of his employment in 1791, L’Enfant was frequently going over their heads and straight to the President with many of his plans and concerns. On November 28, 1791, George Washington received a letter from him regarding a building under construction that would cut into one of his proposed streets.

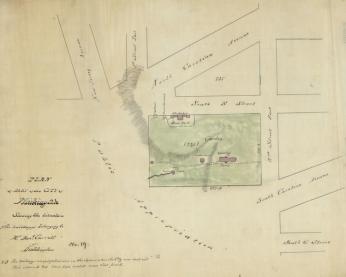

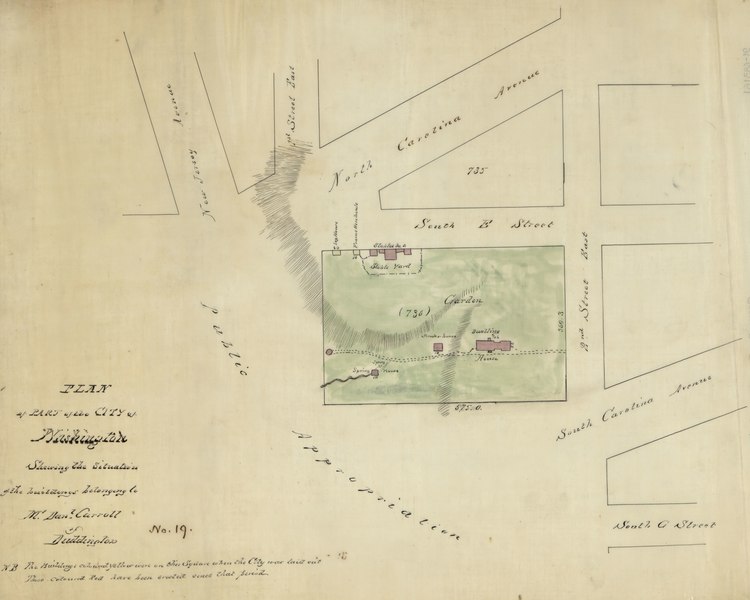

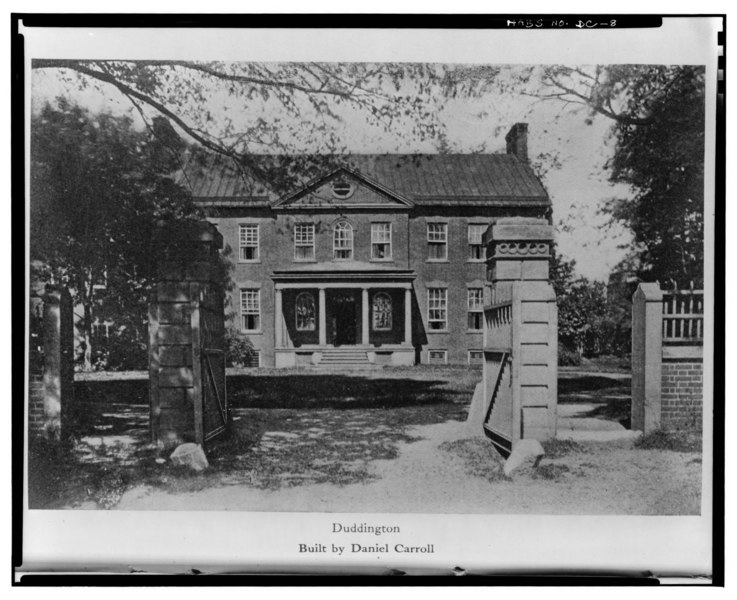

The same day, Washington also got a letter from the very angry owner of that property, Daniel Carroll of Duddington, who planned to serve a bill against L’Enfant for trying to destroy his house. Carroll of Duddington also happened to be the nephew of Commissioner Daniel Carroll of Rock Creek (Yeah, it’s a lot of Daniels) whose family allotted a large parcel of land to be used toward the creation of D.C.[2]

Carroll of Duddington wrote:

Sir,

Since I had the honor to write you a few days past, informing you of my disagreeable situation, Major L’Enfant has proceeded with his hands to the demolishing of my building which he has in great Measure effected, having entirely destroyed the roof, & thrown down the greater part of the upper story, in fine the building is ruined, this appears to be the most arbitrary act ever heard of.”[3]

The President wrote immediately to L’Enfant, hoping to do some damage control. Since this was long before eminent domain became legal in this country, he urged:

As a similar case cannot happen again (Mr Carrolls house having been begun before the Federal District was fixed upon) no precedent will be established by yielding a little in the present instance; and it will always be found sound policy to conciliate the good-will rather than provoke the enmity of any man, where it can be accomplished without much difficulty, inconvenience or loss. Indeed the more harmoniously this, or any other business is conducted the faster it will progress, & the more satisfactory will it be.”[4]

Washington wrote back to Carroll of Duddington as well, pleading with him to “think it more advisable to quash, than prosecute the chancery injunction,” in other words, to avoid any legal action toward L’Enfant.[5]

But while Carroll eventually dropped the injunction, L’Enfant seemed deaf to Washington’s entreaties. While he did not wish to oppose the President’s “paternal goodness,” he continued with the demolition and believed it impossible not to, considering that the house stood in the way of his design. He scoffed at Carroll of Duddington’s complaints, and told George Washington that any “regret is tempered from a trust that you are sufficiently satisfied I proceeded from principle consistent with the first Steps I had taken.”[6]

After all, before he ordered the house to be torn down, L’Enfant did send a note to Carroll of Duddington asking him kindly if he would prefer to destroy his home himself.[7]

Washington may have been pulling out his hair at this point in the saga, but he responded to L’Enfant politely, reminding him that he should be taking his orders from the Commissioners instead of going straight to the President, and that he should stop viewing them as an enemy.[8]

The Commissioners, however, were not exactly on L’Enfant’s side. Daniel Carroll of Rock Creek insisted that, if necessary, he would testify not as a Commissioner, but on behalf of his nephew, who he considered to be in the right.[9]

Thankfully, it seemed the affair would never come to that. The Commissioners wrote Thomas Jefferson on December 10, 1791, to inform him that, despite the unwarranted demolition of a house, “The Major has indeed done us the Honour of Writing us a Letter, Justifying his conduct. We have not noticed it, and believe as we are likely to get every thing Happily adjusted between Mr. Carroll and him, it will be most prudent to drop all explanations.”[10]

Washington was elated. This was one less headache for him to deal with in establishing the new Nation and its Capital. Besides that, despite his reprimands of L’Enfant, he believed that Carroll of Duddington was “equally to blame” based on the different accounts he had heard of the matter.[11]

But this truce between L’Enfant and the Commissioners lasted less than two weeks, when the Commissioners discovered that L’Enfant was still proceeding with the total destruction of Carroll of Duddington’s house against all orders.[12]

And then, to heap a few more straws on the camel’s back, L’Enfant began writing Washington about the home of wealthy landowner Notley Young (who also gave a significant portion of his land to the Capital City). To Mr. Young’s bewilderment, L’Enfant thought this house might also be “a nuisance” in the way of a future street.[13]

If the Commissioners had grievances with L’Enfant, he was equally infuriated with them for arresting one of his assistants, Mr. Roberdeau, for obeying L’Enfant’s orders over theirs on several occasions.[14]

Eventually, L’Enfant got so mad that he threatened to quit over it. And Washington could defend him no longer. The Commissioners wrote of their frustration with L’Enfant and his lackeys:

The Difficulty of having to do with such a Temper is enough, it is increased by Addition of Volunteers and what is no uncommon effect of such a Spirit the circulation of infamous Falshoods, to the prejudice of our Characters.”[15]

In short, they were entirely fed up with him. So L’Enfant’s threatened resignation didn’t carry a lot of weight.

Washington wrote his friend expressing his disappointment and effectively ending L’Enfant’s involvement in designing the District.

The continuance of your services (as I have often assured you) would have been pleasing to me, could they have been retained on terms compatible with the law. Every mode has been tried to accommodate your wishes on this principle, except changing the Commissioners (for Commissioners there must be, and under their direction the public buildings must be carried on, or the law will be violated…).”[16]

Okay, so poor L’Enfant was out of a job, but what about the man whose house he tore down? Don’t worry, Washington ordered it to be rebuilt to the same level it was before L’Enfant destroyed it. Some of the building materials were even salvageable,[17] so the house was basically just moved over a bit—from New Jersey Avenue to an adjacent lot between D and E Streets (it was destroyed again in 1886).[18]

L’Enfant’s career declined, meanwhile, and he quietly lived out the rest of his days in Prince George’s County, Maryland, at the estate of his friend, William Dudley Digges—whose wife was Daniel Carroll of Duddington’s daughter.[19] That must’ve made for some interesting conversations over dinner.

Footnotes

- ^ “To George Washington from Pierre L’Enfant, 21 November 1791,” Founders Online, National Archives, accessed April 11, 2019, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/05-09-02-0124. [Original source: The Papers of George Washington, Presidential Series, vol. 9, 23 September 1791 – 29 February 1792, ed. Mark A. Mastromarino. Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 2000, pp. 219–225.]

- ^ Kite, Elizabeth S. "The Washington Carrolls and Major L'Enfant." The Catholic Historical Review 15, no. 2 (1929): 125-42. http://www.jstor.org/stable/25012609.

- ^ “To George Washington from Daniel Carroll of Duddington, 28 November 1791,” Founders Online, National Archives, accessed April 11, 2019, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/05-09-02-0135. [Original source: The Papers of George Washington, Presidential Series, vol. 9, 23 September 1791 – 29 February 1792, ed. Mark A. Mastromarino. Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 2000, pp. 236–237.]

- ^ “From George Washington to Pierre L’Enfant, 28 November 1791,” Founders Online, National Archives, accessed April 11, 2019, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/05-09-02-0136. [Original source: The Papers of George Washington, Presidential Series, vol. 9, 23 September 1791 – 29 February 1792, ed. Mark A. Mastromarino. Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 2000, pp. 237–238.]

- ^ “From George Washington to Daniel Carroll of Duddington, 2 December 1791,” Founders Online, National Archives, accessed April 11, 2019, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/05-09-02-0145. [Original source: The Papers of George Washington, Presidential Series, vol. 9, 23 September 1791 – 29 February 1792, ed. Mark A. Mastromarino. Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 2000, p. 244.]

- ^ “To George Washington from Pierre L’Enfant, 7 December 1791,” Founders Online, National Archives, accessed April 11, 2019, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/05-09-02-0157. [Original source: The Papers of George Washington, Presidential Series, vol. 9, 23 September 1791 – 29 February 1792, ed. Mark A. Mastromarino. Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 2000, pp. 263–266.]

- ^ Kite, Elizabeth S. "The Washington Carrolls and Major L'Enfant." The Catholic Historical Review 15, no. 2 (1929): 137.

- ^ “From George Washington to Pierre L’ Enfant, 13 December 1791,” Founders Online, National Archives, accessed April 11, 2019, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/05-09-02-0170. [Original source: The Papers of George Washington, Presidential Series, vol. 9, 23 September 1791 – 29 February 1792, ed. Mark A. Mastromarino. Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 2000, pp. 281–283.] and “From George Washington to Pierre L’Enfant, 2 December 1791,” Founders Online, National Archives, accessed April 11, 2019, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/05-09-02-0146. [Original source: The Papers of George Washington, Presidential Series, vol. 9, 23 September 1791 – 29 February 1792, ed. Mark A. Mastromarino. Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 2000, pp. 244–245.]

- ^ “Enclosure: Daniel Carroll’s Case, 8 January 1792,” Founders Online, National Archives, accessed April 11, 2019, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/05-09-02-0239-0002. [Original source: The Papers of George Washington, Presidential Series, vol. 9, 23 September 1791 – 29 February 1792, ed. Mark A. Mastromarino. Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 2000, pp. 397–399.]

- ^ “To Thomas Jefferson from the Commissioners of the Federal District, 10 December 1791,” Founders Online, National Archives, accessed April 11, 2019, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Jefferson/01-22-02-0358. [Original source: The Papers of Thomas Jefferson, vol. 22, 6 August 1791 – 31 December 1791, ed. Charles T. Cullen. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1986, pp. 388–389.]

- ^ “From George Washington to the Commissioners for the District of Columbia, 18 December 1791,” Founders Online, National Archives, accessed April 11, 2019, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/05-09-02-0183. [Original source: The Papers of George Washington, Presidential Series, vol. 9, 23 September 1791 – 29 February 1792, ed. Mark A. Mastromarino. Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 2000, pp. 292–295.]

- ^ “To George Washington from the Commissioners for the District of Columbia, 21 December 1791,” Founders Online, National Archives, accessed April 11, 2019, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/05-09-02-0189. [Original source: The Papers of George Washington, Presidential Series, vol. 9, 23 September 1791 – 29 February 1792, ed. Mark A. Mastromarino. Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 2000, pp. 298–301.]

- ^ Kite, Elizabeth S. comp. L’Enfant and Washington, 1791–1792: Published and Unpublished Documents Now Brought Together for the First Time. Baltimore, 1929.

- ^ “To George Washington from Pierre L’Enfant, 6 February 1792,” Founders Online, National Archives, accessed April 11, 2019, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/05-09-02-0319. [Original source: The Papers of George Washington, Presidential Series, vol. 9, 23 September 1791 – 29 February 1792, ed. Mark A. Mastromarino. Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 2000, pp. 542–544.]

- ^ “To George Washington from the Commissioners for the District of Columbia, 21 January 1792,” Founders Online, National Archives, accessed April 11, 2019, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/05-09-02-0283. [Original source: The Papers of George Washington, Presidential Series, vol. 9, 23 September 1791 – 29 February 1792, ed. Mark A. Mastromarino. Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 2000, pp. 486–487.]

- ^ “From George Washington to Pierre L’Enfant, 28 February 1792,” Founders Online, National Archives, accessed April 11, 2019, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/05-09-02-0369. [Original source: The Papers of George Washington, Presidential Series, vol. 9, 23 September 1791 – 29 February 1792, ed. Mark A. Mastromarino. Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 2000, pp. 604–606.]

- ^ “From Thomas Jefferson to the Commissioners of the Federal District, 6 March 1792,” Founders Online, National Archives, accessed April 11, 2019, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Jefferson/01-23-02-0186. [Original source: The Papers of Thomas Jefferson, vol. 23, 1 January–31 May 1792, ed. Charles T. Cullen. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1990, pp. 224–225.]

- ^ Wharton, Anne Hollingsworth. Social Life in the Early Republic. Philadelphia & London: J.B. Lippincott Company. 1902. 48.

- ^ Kite, Elizabeth S. "The Washington Carrolls and Major L'Enfant." The Catholic Historical Review 15, no. 2 (1929): 140.

![Sketch of the mythical fuan by Pearson Scott Foresman. [Source: Wikipedia]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2023-10/Goatman_Wikipedia_Faun_2_%28PSF%29.png?h=64a074ff&itok=C9Qh-PE1)