A Filipino Literary Landmark: The Manila House in D.C.

2422 K St. NW, nestled in the Foggy Bottom neighborhood just down the street from the George Washington University, looks like any other D.C. row house. But for the Filipino community in D.C. during the 1930s through the 1950s, it was a haven - a source of culture, community, and comfort. As those who remember it fondly today can testify, 2422 K St. NW wasn’t just a row house; it was the Manila House.

Although today there are only a couple of Filipino-Americans still living who visited the Manila House in its heyday, stories of the house have been documented by Filipino writers and have been passed down in families. “I first learned about Manila House 24 years ago, in 1993, when I interviewed my father Clemente Cacas and his friends, Fernando Aguilar and Mateo Perez,” recalled Rita Cacas, writer and archivist of D.C. Filipino history.[1] “They described the house as a place for taxicab drivers like themselves to hang out, play cards and attend dances for ten cents on weekends.”[2]

It was a place of leisure for certain, but the Manila House was also much more than that. It provided Filipino-Americans a unique space to connect with each other and with their culture in a city that could be isolating.

Filipinos began to settle in and around D.C. as early as 1900, but their numbers were small.[3] According to U.S. Census data, there were only 294 Filipinos living in D.C., 327 in Maryland, and 126 in Virginia as of 1930.[4] The Asian population at large in D.C. was only 780, or 0.2% of D.C.’s total population.[5] Many Filipinos came to the D.C. area to work as government workers in the office of the Philippine Resident Commissioner, as cab drivers, or as officers in the military[6]. Many Filipino men enlisted in the U.S. Navy in particular. Since Washington was the center of government work and Annapolis housed the U.S. Naval Academy, the D.C., Maryland, Virginia area was attractive to Filipino immigrants who sought work in those fields. Still, Filipinos found themselves just one small part of a large metropolitan area.

The city was still largely segregated, with African-American communities in the southeast and southwest quadrants of Washington and white communities in the northwest and northeast quadrants.[7] Nila Toribio-Straka was just a child during the 1940s, but she remembers how her parents had to navigate the racial dynamics of the city. “[They] would be walking down Pennsylvania Ave, or wherever… and if a Caucasian person walked toward them, they had to cross the street and walk to the other side,” she explains.[8] “If they were on a bus, and again if a Caucasian came, they had to go to the back of the bus.”[9]

For much of the twentieth century, Filipino-Americans in Washington found themselves stuck in this in-between. In 1937, though, a Filipino organization in D.C. called Visayan Circle purchased what would become the Manila House. Asuncion Gaudiel managed the house along with her husband, Gil Eposo. As Toribio-Straka, Gaudiel’s granddaughter, remembers, “The warmth that [Gaudiel] gave to these people of the Manila house” was astounding. “These were perfect strangers,” says Toribio-Straka, “but she treated them like family.” It makes sense, then, that Gaudiel was better known as Manang, or big sister, by all who visited the house. Although the original intent of Manila House was to board bachelors, it soon grew to become a cultural gathering place for all Filipinos of the DMV area.

Gaudiel’s home-cooked meals were famous among the Filipino community of Washington. She and her husband grew a fresh vegetable garden beside the house and served what Santos called “the finest Filipino dishes.”[10] Toribio-Straka remembers “the strong, delicious smell of pork adobo, and the vinegary taste of sinigang” that constantly filled the house.[1] As Toribio-Straka remarks, “Manila House was a refuge for Filipino[s]…a place for them to congregate, where they fe[lt] like they ha[d] a home away from home.”[1]

This home grew increasingly important after the outbreak of World War II in 1939. Almost all Filipino’s living in D.C. still had family back in the Philippines, and they had to watch the war’s impact on their home country from afar. The Manila House provided a place for them to express their worries with each other and share news about the Japanese occupation of their homeland.[11] According to a Washington Post article published in 1941, the “men of the Manila Club, 2422 K St., Northwest” held a “a stoic concern over the fate of relatives living where the Japanese now strike” and a “confident belief that with sufficient equipment the Philippines will stand.”[12] The article quoted several Filipino men, all of whom gathered together at the Manila House: Justiniano Ferrer, lawyer and “president of the Social Club;” S.T. Castro, a U.S. government worker; Ahena Duley, a taxidriver; and Angelo Bayon, a painter.[12] “[The Japanese] take advantage of us whenever they can. We’re all so angry at them we can hardly keep still,” expressed Ferrer in the article.[12] “The eyes of Ahena Duley were misty,” wrote the Post, “as he thought of his parents on the Lingayen Gulf and his cousins in the Philippine army.”[12]

Even after the war, the Manila House remained a safe space in the city. Evangeline Parades, now 101, remembers evenings where she would go to the Manila House after work to help check in the house’s visitors. “I was so proud to volunteer at the door,” she recalled, remembering the house as a place of “fun times”.[1]

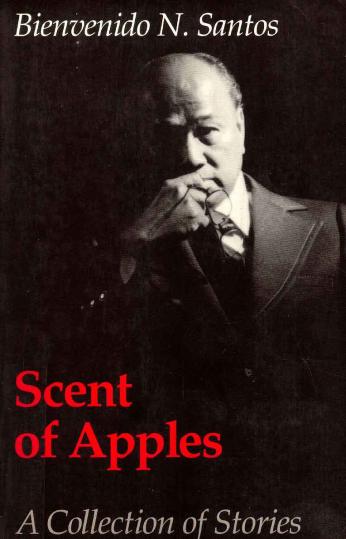

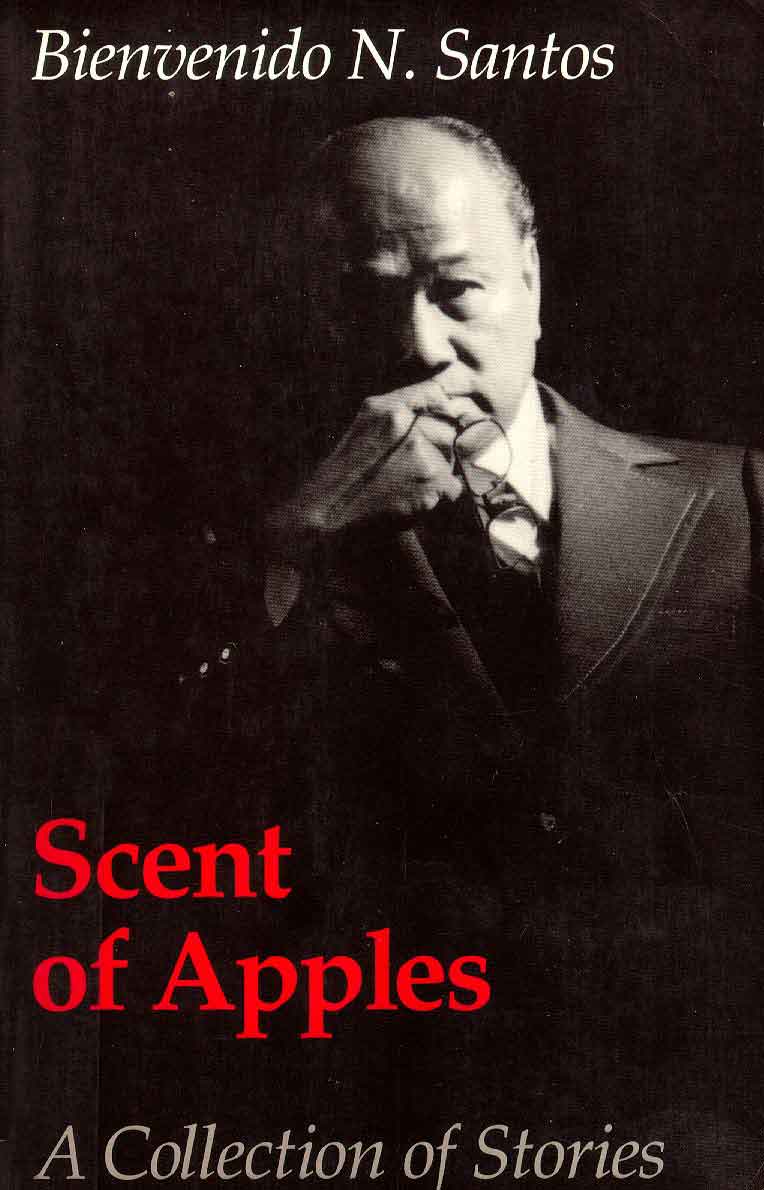

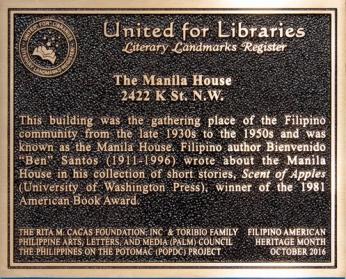

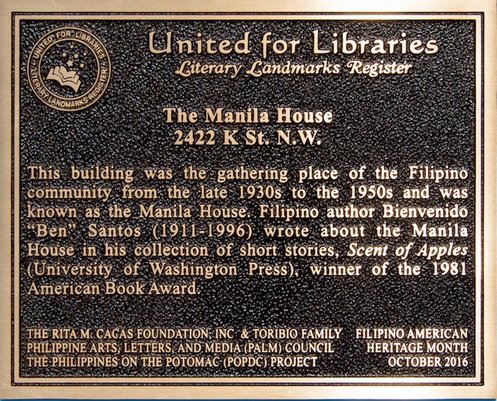

The Manila House put on dances and hosted artists and writers, most notably Diosdado Yap, editor and publisher of Bataan Magazin, and Bienvenido N. Santos.[11] Santos, who lived in Washington in the 1940s, recalled visiting Manila House often.[13] “I lived with a [Filipino] taxi driver, and he was very fond of taking me there. He didn’t like his American wife’s cooking. Besides, there we could eat with our hands.”[13] Reveling in the opportunity to “listen to expatriates and absorb their stories,” Santos later wrote about the house in his short story collection, The Scent of Apples, which won the American book award in 1981.[11]

Following the war, the Filipino-American community in D.C. grew as the Philippines gained independence and U.S. immigration and naturalization laws allowed for expanded citizenship. By 1970, several thousand Filipinos were living in the D.C. area.[14]As most settled in the suburbs, Manila House’s place as a cultural center began to slip and, according to the District of Columbia’s Recorder of Deeds, the Visayan Circle released the Manila House property in 1976.[11]

Still, over 40 years later, the Manila House remains an important landmark for the Filipino-American community of D.C. In recent years, Titchie Carandang-Tiongson and Erwin Tiongson, co-directors of the Philippines on the Potomac (POPDC) Project, have done much to uncover the house’s history. The Tiongsons, along with Rita Cacas, a former archivist and museum specialist, were the ones who recently traced the original location of the Manila House, identifying it as 2422 K. St NW. The house now belongs to St. Paul’s Episcopalian Parish. Fr. Humphrey; but the Tiongsons and Cacas, together with the larger Filipino D.C. community, worked with the American Library Association to recognize the Manila House as a literary landmark, in honor of Bienvenido N. Santos.[1] A dedication ceremony was held on May 6, 2017, and Filipino-Americans of many generations came together to recognize the Manila House with a bronze plaque.[15]

“I never imagined we would get to this day,” said Rita Cacas at the ceremony.[1]

So yes, if you’re passing through Foggy Bottom, it may be easy to breeze past 2422 K. St. NW.; but if you stop and listen carefully, you may just be able to hear one of the many treasured tales housed within its walls.

Footnotes

- a, b, c, d, e, f Melegrito, Jon. “Fil-Ams celebrate Manila House, a literary landmark in Washington D.C.” Inquirer, 17 May 2017, https://usa.inquirer.net/3734/fil-ams-celebrate-manila-house-literary-l….

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Rita M. Cacas and Juanita Tamayo-Lott. Filipinos in Washington D.C. District of Columbia, Arcadia Publishing, 23 November 2009, 35.

- ^ Campbell Gibson and Kay Jung. “Population Division: HISTORICAL CENSUS STATISTICS ON POPULATION TOTALS BY RACE, 1790 TO 1990, AND BY HISPANIC ORIGIN, 1970 TO 1990, FOR THE UNITED STATES, REGIONS, DIVISIONS, AND STATES.” United States Census Bureau. Working paper series (United States. Bureau of the Census. Population Division), no. 56. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Census Bureau, 2002.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Rita M. Cacas and Juanita Tamayo-Lott. Filipinos in Washington D.C. District of Columbia, Arcadia Publishing, 23 November 2009

- ^ Rita M. Cacas and Juanita Tamayo-Lott. Filipinos in Washington D.C. District of Columbia, Arcadia Publishing, 23 November 2009, 90.

- ^ Mary Estacion. “INSIDE THE MANILA HOUSE, A LITERARY LANDMARK IN WASHINGTON D.C.” Balitang America. ABS-CBN News, 19 October 2019.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Ibid.

- a, b, c, d Titchie Carandang-Tiongson. “The Manila House in Washington D.C.” Positively Filipino Magazine. Positively Filipino, 10 May 2017, http://www.positivelyfilipino.com/magazine/the-manila-house-in-washingt….

- a, b, c, d "Article 1 -- no Title." The Washington Post (1923-1954), Dec 26 1941, p. 3.

- a, b Edilberto N. Alegre and Doreen G. Fernandez “Bienvenido N. Santos.” The Writer and His Milieu: An Oral History of First Generation Writers in English. Manila, De La Salle University Press, 1984. p. 250 and 251

- ^ Census records from 1940 documented 712 Filipinos living in D.C., 615 in Maryland, and 645 in Virginia; By 1970, this population had grown to 1,662 in D.C., 5,170 in Maryland, and 7,496 in Virginia. “1970 census of population. Characteristics of ... v.1/pt.1 sec.1. United States,” Hathitrust Digital Library, United States Census Bureau, https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=uva.x004407896&view=1up&seq=57, 301

- ^ “The Former Manila House at 2422 K St., NW.,” The Rita M. Cacas Foundation, Inc., http://rmcacas.foundation/manila-house-literary-landmark.html

![Sketch of the mythical fuan by Pearson Scott Foresman. [Source: Wikipedia]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2023-10/Goatman_Wikipedia_Faun_2_%28PSF%29.png?h=64a074ff&itok=C9Qh-PE1)