"Together, Together:" D.C.'s Chinese March En Mass for the First Time

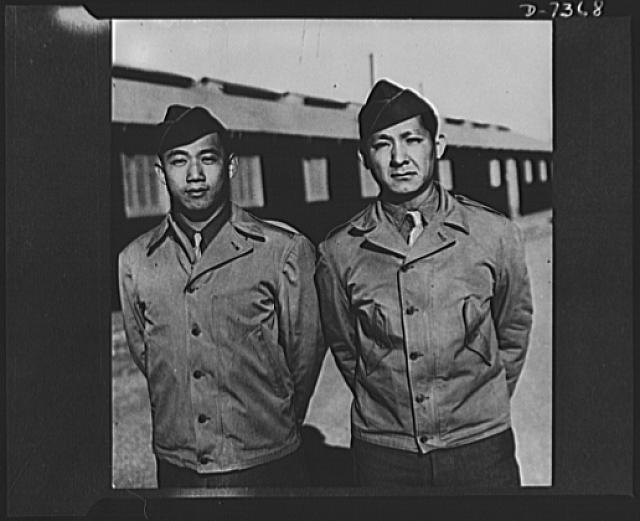

As the new PBS documentary Asian-Americans notes, many Asian-American immigrants maintained strong bonds to their home countries and were deeply affected by World War II conflicts that occurred in the Pacific theater. In fact, even before U.S. involvement and the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor in 1941, Asian-Americans from the D.C. area closely followed the brewing conflict between China and Japan.

Although construction of the Federal Triangle forced DC’s Chinatown residents to relocate in the 1930s, the Chinese community in the city remained strong. Many still had close relatives in China. Japanese imperialist expansion into China and the resulting Second Sino-Japanese War moved Chinese-Americans at home to organize, and those in the DMV area were no exception. On July 7, 1938, in recognition of the one year anniversary of the war’s outbreak, D.C.’s Chinese marched in mass for the first time.[1]

Chinese New Year parades were common, but even so, this was the first time in the city’s history that such a major portion of D.C.’s Chinese had gathered together.[1] It was a significant demonstration of unity. Members of the Chinese Embassy, the Chinese Student Club, the Chinese Merchants’ Association, and the Chinese Women’s Association showed their support. Even Tong[2] brotherhood groups temporarily set aside their rivalries in remembrance of the war.[3] They may have had their disagreements, but they all shared common empathy for the 1,000,000 Chinese soldiers, women, and children who had perished in war. In remembrance of those lost, Chinese in Washington fasted meat for the day and donated money to loved ones in China. For once, Chinatown’s usually bustling “laundries, restaurants, art and antique shops, and noodle factories” were quiet as a crowd of 700 marched silently through the streets of the city.

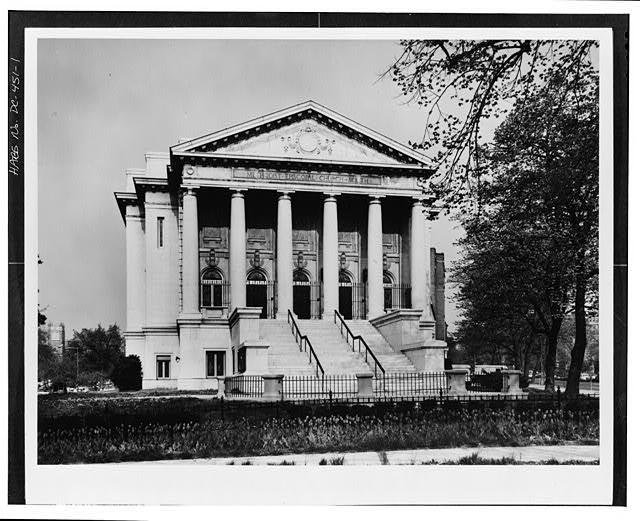

The march began at the headquarters of the Chinese National Salvation Association of Washington (607 H Street NW), which was situated in the center of the newly relocated Chinatown. Those in the crowd proudly held the Chinese flag, American flag, and banners bearing the words “National Memorial Day, July 7,” “Support Chinese Battle for Peace and Democracy,” “Down With Japanese Militarism,” and “Unity of 450,000,000 Chinese Against Japanese Invaders.”[4] The crowd proceeded up ninth street to the Mount Vernon Methodist Episcopal Church, where they gathered to sing the national Chinese song, “Together, Together,” and hear speeches from the community.[4]

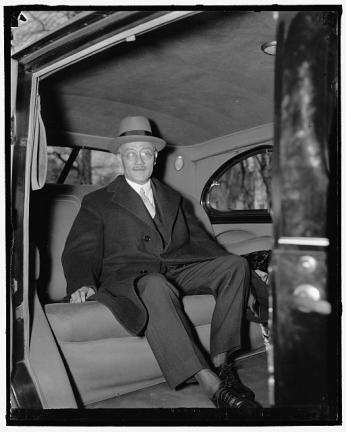

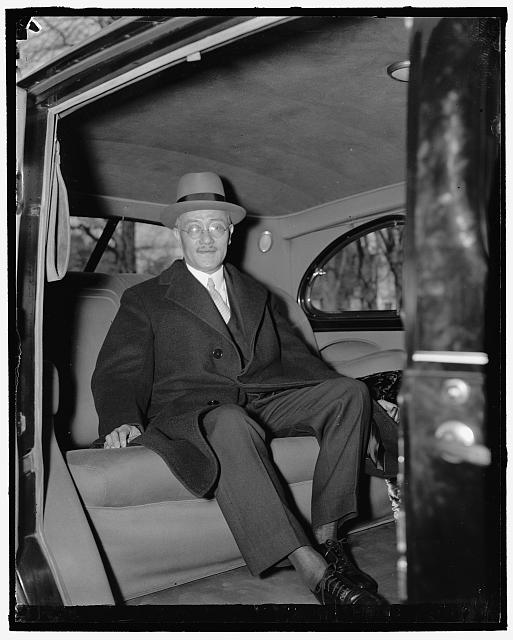

Chinese Ambassador C.T. Wang declared that the march “ha[d] a double significance…It not only mark[ed] the day of the fateful Chinese-Japanese battle around Marco Polo Bridge, but it celebrat[ed] the unexpected Chinese resistance to [Japanese] armies.”[4] Dr. Lin Lin of the Chinese Student Club, who presided over the meeting, remarked, “We are proud that we are going to win the war through national unity.”[3] All but one speech given during the commemoration were given in Mandarin Chinese. Mrs. Charles Franklin, speaking in English on behalf of the Washington Committee for Aid to China, apologized for the “apathy of those Americans who do not do their part to aid China.”[3]

Franklin said her and her associates “were determined to help China win national freedom for democracies all over the world.”[4] Dr. Lin Lin concluded the meeting by reading the will of Dr. Sun Yat Sen, founder of the Chinese republic: “The purpose of the national revolution is to get freedom and equality for China and all nations of the world.”[3]

After the gathering ended at 1 pm, Chinatown’s stores and restaurants opened once again. As The Washington Post noted, D.C.’s Chinese were eager to get back to work earning money for “relief of their country.”[4] This wouldn’t be the last time Chinese-Americans would organize in response to the war, though. Following US involvement in World War II, Asian-Americans were forced to come together as they grappled with both violence in their home countries and anti-Asian-American sentiment present in their local communities. For more on the Asian-American experience during World War II, check out PBS’ Asian-Americans Episode Two: A Question of Loyalty.

Footnotes

- a, b “D.C.'s Chinese March in Mass For First Time: 700 Parade on Anniversary of Invasion, Hear Dr.“The Washington Post (1923-1954); Jul 8, 1938; ProQuest Historical Newspapers: The Washington Post pg. X5

- ^ Brotherhoods, often associated with gang activity.

- a, b, c, d “Chinese March at War’s Anniversary,” Evening Star (published as THE EVENING STAR.), July 7, 1938, page 4

- a, b, c, d, e “D.C.'s Chinese March in Mass For First Time: 700 Parade on Anniversary of Invasion, Hear Dr.“The Washington Post (1923-1954); Jul 8, 1938; ProQuest Historical Newspapers: The Washington Post pg. X5

![Sketch of the mythical fuan by Pearson Scott Foresman. [Source: Wikipedia]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2023-10/Goatman_Wikipedia_Faun_2_%28PSF%29.png?h=64a074ff&itok=C9Qh-PE1)