"Not Fiction, but Fact": Josiah Henson and the Real Uncle Tom's Cabin

When Harriet Beecher Stowe published Uncle Tom’s Cabin in 1852, it wasn’t to universal acclaim. Historians now recognize the novel as a literary landmark, since it sparked renewed frustration and debate over the issue of slavery in the United States; but Stowe faced harsh criticism from pro-slavery politicians and writers. An 1852 issue of the Southern Literary Review published a review that was “on the defensive,” endeavoring to expose the “miserable misrepresentations” of Stowe’s horrific slave-owning characters.[1] As the author picks apart the events of the novel, they emphasize the fact that Stowe is not only an uninformed Northerner, but primarily a dramatist. The review ends with a condescending “suggestion to Mrs. Stowe—that, as she is fond of referring to the Bible, she will turn over, before writing her next work of fiction, to the twentieth chapter of Exodus and there read these words—'THOU SHALT NOT BEAR FALSE WITNESS AGAINST THY NEIGHBOR.’”[2]

In a defensive move of her own, Stowe published a companion piece to her novel, A Key to Uncle Tom’s Cabin, a year after it debuted. Essentially an explainer text, the Key addressed the critical attacks and assured readers that Uncle Tom’s Cabin was, in fact, based on reality. It provided background for all Stowe’s controversial characters—including the titular character himself. Considered the martyr and exemplar of the story, whose goodness and morality contrasts with the evil of the masters, Uncle Tom sacrifices himself to protect the whereabouts of other runaway slaves. Yet some critics thought that he was too saintly to be real—and that the story of his death was an extreme and unrealistic depiction of slave life. Stowe disagreed. “The character of Uncle Tom has been objected to as improbable,” she wrote, “and yet the writer has received more confirmations of that character, and from a great variety of sources, than of any other in the book.”[3] Though she knew many virtuous men like Uncle Tom, she named one man in particular as the main source of inspiration: “the venerable Josiah Henson.”[4]

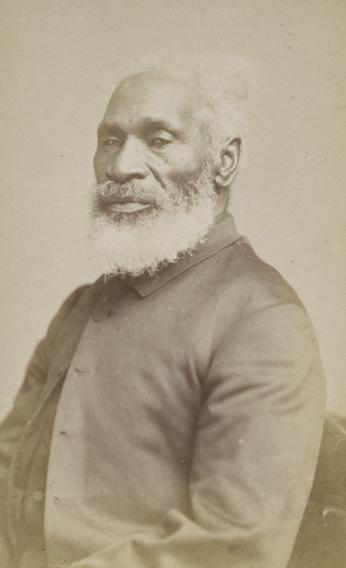

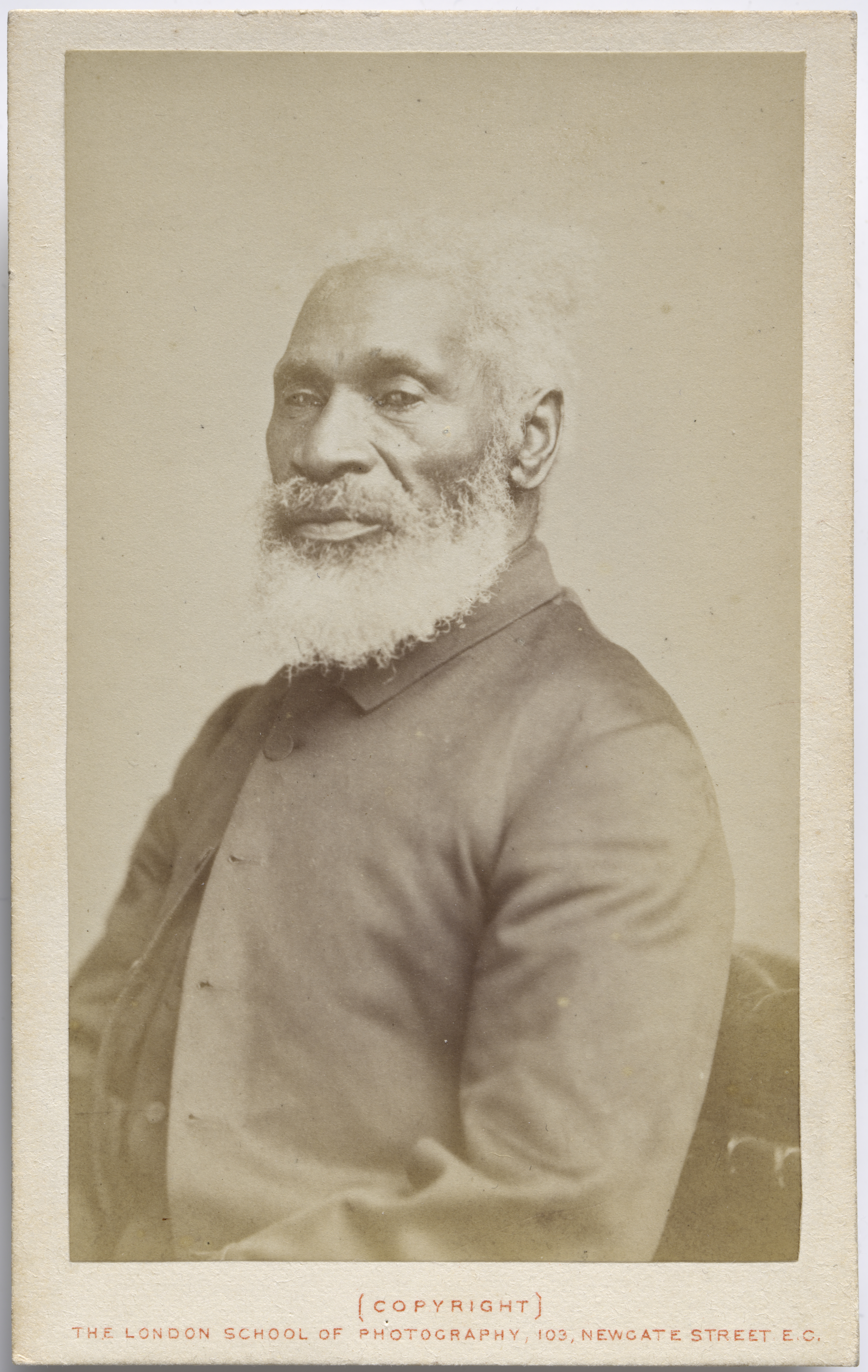

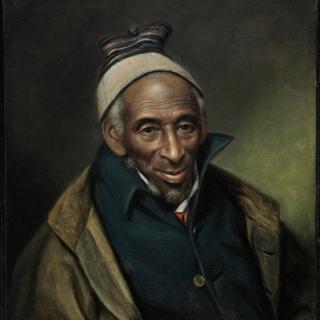

Despite this claim to fame, Henson is not a well-known name in American history—or even in the Washington area, where he was enslaved for many years. Born into bondage in Maryland, he lived in Montgomery County before eventually escaping to Canada—there, he served in the army, became a preacher, and established a prosperous settlement for escaped slaves. In 1849, he dictated his incredible life story to the abolitionist Samuel A. Eliot, who published the account as The Life of Josiah Henson, Formerly a Slave, Now an Inhabitant of Canada, as Narrated by Himself. The book was popular amongst Eliot’s fellow abolitionists in New England, but it only achieved national recognition after Stowe referenced Henson’s “published memoirs” in her Key.[5] Although he became irrevocably linked with the character he inspired, he used his newfound fame to promote his own work.

In the decade preceding the Civil War, literature about slavery was extremely popular—white anti-slavery novels like Uncle Tom’s Cabin became bestsellers in America and abroad, while pro-slavery “anti-Tom” novels circulated in the South. But former slaves also wrote narratives of their firsthand experiences, books and articles that were far more powerful than any novels. Instead of relying on their fictional counterparts, famous activists like Frederick Douglass and Harriet Tubman used their own words to further the abolition movement. Dramatic—but true—stories of enslavement and escape, such as Solomon Northup’s Twelve Years a Slave, validated the dramatized accounts published by white authors. Especially as those works became skewed by decades of misinterpretation, the words of former slaves themselves became invaluable—both as historical record and stories of American heroism.

As folklorist Patricia Turner notes, the character of Uncle Tom was particularly distorted in the years after Stowe published her book.[6] Rather than presenting him as the principled, moral paragon of the novel, later stage productions of Uncle Tom’s Cabin recast Tom as a meek, submissive sellout. It’s doubtful Josiah Henson could have predicted the extent to which his fictional alter ego would be co-opted in later years, but he must have felt the pressure to tell his own story even in his lifetime. Capitalizing on the public fascination with slave experiences and the popularity of Uncle Tom’s Cabin, Henson published an extended version of his memoir in 1858. Though he advertised himself as the real-life Uncle Tom, even including a prologue written by Stowe, Henson knew that his book carried more weight than the novel. “The story has this advantage,” he said. “That it is not fiction, but fact; and it will be found fruitful in instruction by those who attentively consider its lessons.”[7] Certainly, his story is one that no author could invent.

Josiah Henson was born on a farm in Charles County, Maryland, in 1789. Even in his childhood, he observed and experienced the horrors of slavery. His first memory was of his father, “with his head bloody and back lacerated,” after suffering a particularly harsh punishment.[8] Henson’s father had struck the master while protecting his wife from sexual assault, warranting an organized beating and fifty lashes. He sunk into a deep depression, so far removed that “no fear or threats of being sold to the far south—the greatest of all terrors to the Maryland slave—would render him tractable.”[9] The fear was justified; he was later sold and sent to Alabama, never to be heard from again. When their master died, the family suffered further separation at the auction block, each sold separately to different masters. After witnessing the sale of her other children, Henson’s mother begged her new owner, Isaac Riley, to purchase the five-year-old Henson “as well as herself, and spare to her one of her little ones at least.”[10] Riley not only ignored her, he beat her into silence. These were Henson’s “earliest observations of men,” which left a bitterness that “cannot diminish to any individual who suffers it.”[11]

Riley eventually relented, so Henson’s separation from his mother did not last long. He grew up working in the fields of Riley’s farm in Montgomery County, becoming strong, intelligent, and well-liked amongst his “associates in misery.”[12] Though Henson did not like his master, describing him as an “unprincipled and cruel” man, he eventually won Riley’s respect and became the farm’s overseer and manager.[13] At the markets of Washington and Georgetown, shoppers knew him fondly as “Siah” or “Si.”[14]

In 1828, Henson had a chance for freedom. Riley’s farm had fallen on hard times; for a while, he had sent his slaves to work at his brother’s plantation in Kentucky. While there, Henson met a Methodist preacher who persuaded him to work towards buying himself, promising to aid him in procuring the funds. “A new era in my history now opened” when his new master gave him permission to travel back East—though unaware of Henson’s ultimate goal.[15] He stopped in Ohio first, where he had the opportunity to preach in Methodist circles for donations. What affected him most, though, was experiencing life in a free state. “Everywhere I met with kindness,” Henson wrote. “The contrast between the respect with which I was treated and the ordinary abuse…of plantation life, gratified me in the extreme.”[16] When he finally arrived in Maryland and reunited with Riley, his gentlemanly manner “sorely puzzled” his old master, “and I soon saw it began to irritate him. The clothes I wore were certainly better than his.”[17] Henson offered all of his money to Riley in exchange for freedom; surprisingly, despite the perceived hostility, Riley agreed. A note was drawn up stating that, after paying a remaining $100 fee, Henson would no longer be Riley’s property.

But upon his return to Kentucky, Henson discovered a devastating truth. Not having seen the note himself, he didn’t realize that Riley added an extra zero to the amount owed—and he had no reasonable hope of obtaining $1000. Worse, he suspected that his masters meant to sell him as punishment for his efforts. Faced with possible separation from his family, he decided that he could suffer no more. “And now occurred one of those sudden, marked interpositions of Providence, by which in a moment the whole current of a human being’s life is changed”: Henson decided to escape with his wife and children.[18]

The family left Kentucky in 1830, bound for the safety of Canada. They only traveled at night, making occasional stops to sleep and beg for food. In Ohio, Henson reunited with old friends who provided for the family. They even came across a tribe of American Indians, feasting with them and spending the night in their camp. After nearly a month of travel, “my feet first touched the Canada shore. I threw myself on the ground, rolled in the sand, seized handfuls of it…and danced round till, in the eyes of several who were present, I passed for a madman.”[19] When someone questioned his seemingly odd behavior, Henson beamed. “Don’t you know? I’m free!”[20]

Henson went on to live a prosperous life in Canada. He worked on farms near Ontario, continued to preach, and even led a Canadian Army militia in the Rebellion of 1837. Perhaps most notably, he and associates established a colony for fellow freedmen and abolitionists, a safe haven for runaway slaves. The Dawn Settlement, as it was known, encouraged education and vocational training, eventually becoming a self-sufficient community. On a few journeys back to the United States, Henson himself “conducted” runaway slaves to his new settlement. “After I had tasted the blessings of freedom, my mind reverted to those whom I knew were groaning in captivity, and I at once proceeded to take measures to free as many as I could.”[21] At its peak, the Dawn Settlement was home to 500 former slaves.

So really, Henson’s life story doesn’t much resemble his fictional portrayal in Stowe’s book—nor the reinterpreted stage versions, for that matter. Unlike Stowe’s Uncle Tom, Henson refused to surrender to his fate and die a slave; his determination and passion saved the lives of hundreds of people. But thanks to the success of the novel, Henson’s achievements became common knowledge. Though he still referred to himself as the real Uncle Tom, he became a noteworthy activist in his own right. In 1861, he even traveled to England, where he met Queen Victoria and attended the International Exhibition. He continued to advocate for the rights of his people until his death in 1883—aged ninety-three.

When paying tribute to the man who inspired her most famous character, Stowe wrote that no person’s story was “more striking, more characteristic and instructive, than that of Josiah Henson.”[22] She, like so many others, regarded him as a hero. For his part, Henson just wanted a better, fairer world. “My task is done, if what I have written shall inspire a deeper interest in my race, and shall lead to corresponding activity in their behalf I shall feel amply repaid.”[23]

A part of his world still exists in North Bethesda. The Riley-Bolton House, once the home of Isaac Riley, is part of a 1.43-acre park property now named for Josiah Henson. Locally known as “Uncle Tom’s Cabin,” it has been open to visitors since 2006, when it was purchased by Montgomery Parks as a historic site and museum. In January, the county announced plans to redevelop the site into a major new museum celebrating the author and activist, hoping to spread awareness of his remarkable—and true—story.

Footnotes

- ^ “Notices of New Works,” Southern Literary Review 18, No. 10 (October 1852), 631.

- ^ “Notices of New Works,” 638.

- ^ Harriet Beecher Stowe, A Key to Uncle Tom’s Cabin: Presenting the Original Facts and Documents upon Which the Story Is Founded, Together with Corroborative Statements Verifying the Truth of the Work (Boston: Jewett, 1854), 38.

- ^ Stowe, 43.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ “Why African-Americans Loathe ‘Uncle Tom,’” Tell Me More on NPR, July 30, 2008, https://www.npr.org/templates/story/story.php?storyId=93059468

- ^ Josiah Henson, The Life of Josiah Henson, Formerly a Slave, Now an Inhabitant of Canada, as Narrated by Himself, transcribed by Samuel A. Eliot (Applewood Books: 2002), 3.

- ^ Josiah Henson, Truth Stranger Than Fiction: Father Henson’s Story of His Own Life (Boston: John P. Jewett and Company, 1858), 2.

- ^ Henson, Truth Stranger Than Fiction, 7.

- ^ Henson, The Life of Josiah Henson, 9.

- ^ Henson, Truth Stranger Than Fiction, 13.

- ^ Henson, The Life of Josiah Henson, 11.

- ^ Henson, The Life of Josiah Henson, 10.

- ^ Henson, The Life of Josiah Henson, 27.

- ^ Henson, Truth Stranger Than Fiction, 63.

- ^ Henson, Truth Stranger Than Fiction, 65.

- ^ Henson, Truth Stranger Than Fiction, 67.

- ^ Henson, Truth Stranger Than Fiction, 96.

- ^ Henson, Truth Stranger Than Fiction, 127.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Henson, Truth Stranger Than Fiction, 144.

- ^ Harriet Beecher Stowe, “Preface,” in Truth Stranger Than Fiction, iii.

- ^ Henson, Truth Stranger Than Fiction, 212.

![Sketch of the mythical fuan by Pearson Scott Foresman. [Source: Wikipedia]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2023-10/Goatman_Wikipedia_Faun_2_%28PSF%29.png?h=64a074ff&itok=C9Qh-PE1)