In the 1850s, Maryland Courts Considered Whether Freeing Slaves was Proof of Insanity

The 1850s Maryland court case Townshend v. Townshend is not one most people are familiar with. In fact, the only place it might be met with recognition is in a law classroom, where any good student will tell you that it established insane delusion in the United States: a legal doctrine which allows a judge to void legal documents written “against all reason and evidence” by a testator.1

But the full story usually goes untold: what should have been a simple suit to confirm a few documents became a back-and-forth legal drama that would span nine years, two counties, and decide whether seventy slaves would become free.

MD. [Source: Destination Southern MD]

It began in 1846, when an 81-year-old tobacco farmer from Prince George’s County lay on his deathbed. John Townshend owned a 1300-acre farm and about seventy slaves, which his nephew, Jeremiah, was keen on inheriting. But upon reading his will, John’s heirs, family, and neighbors were shocked to find a clause bequeathing all his property to another group entirely: his slaves, who were now free men and women.

Manumission by last will was perfectly legal in Maryland, and John had already written two other deeds of manumission to take effect upon his death. Appalled, Jeremiah and several other heirs sued to invalidate the will, claiming that John had been “insane since 1794” (over fifty years of his life).2 Despite evidence against the claim, Prince George’s County voided the will: Jeremiah would take over John’s property—including his slaves.

But even without the will, there were still the other deeds of manumission. Two slaves named Jerry and Anthony realized this and decided to file, on behalf of themselves and the others, a petition for freedom.

Slaves had some recourse in Maryland’s courts, but getting there was a daunting process. Representation was expensive, and lawyers had financial incentives to decline: if they failed to win a petition for freedom, they could be responsible for “all legal costs” associated with the trial.3 Proceedings could also only be held in the slaves’ county of residence, where the jury pool would almost certainly be dominated by farmers and slave owners. Not the most sympathetic audience for slaves seeking their liberty.

Despite the odds stacked against them, Anthony and Jerry found an ally in lawyer Thomas Alexander. Alexander’s records are scarce, but he must have been a committed man: accepting enslaved clients and tackling Maryland’s greatly prejudiced legal system was no small feat, and he devoted nine years to the case.

Alexander’s first move was to invoke an 1849 law to move the case out of Prince George’s County. “Prejudice,” he told the court, “may exist in the entire district,” and Jerry and Anthony had no chance for an impartial judgement there. “At their suggestion,” he was petitioning for a removal. Initially, he was successful: Prince George’s sent the case to neighboring Anne Arundel for deliberation.

But Jeremiah Townshend had hired a lawyer too: one with a glittering resume. Thomas Fielder Bowie had served as deputy Attorney-General for Prince George’s County and served in the Maryland legislature. Later he would successfully run for Congress.4 Together, they petitioned for a reversal—and got it. The Anne Arundel County Court refused to hear the case, sending it right back to Prince George’s.

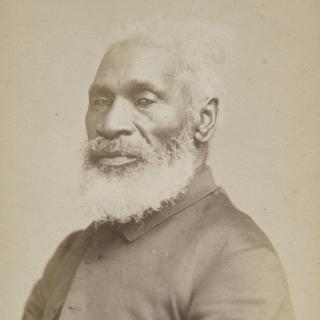

[Source: MD Archives]

Immediately, the slaves and Alexander protested the unfair regression to the Appellate Court, who were not amused by Jeremiah’s tactics.5 Delivering the court’s opinion, Justice Mason wrote with surprising sympathy that it would be “a mockery of justice” to hold the trial in Prince George’s County. “Would it not involve a contradiction of terms,” he wrote, to claim that slaves “shall have the benefit of our courts of justice, but at the same time that his case shall be tried in a county where he cannot have a fair and impartial trial?”6 From then on, the slaves’ petitions would be argued in Anne Arundel County.

Both sides knew the key to the case would lie in proving whether John Townshend had been insane when he wrote the documents in question. If he had, then they were little more than scrap paper. There was a lot to consider and dissect.

In the last decades of his life, John’s spirituality had taken an intense turn. His executor “admitted… for many years before, and up to the time of his death, [Townshend] entertained, or at any rate expressed, some very peculiar views on the subject of religion and the scriptures.”7 John believed “he had seen and conversed with God” and that he had written the will with divine direction.8 Informed by this religious conviction, he directed his executors to pay out of his estate all “certificates as may be necessary to secure to [the ex-slaves’] their full enjoyment of their freedom.”9

Essentially, John embraced a Christian abolitionist philosophy, though its expression was a little odd. Religious opposition to slavery accompanied Maryland’s full-fledged abolition movement, so the philosophy alone—or actions in kind—shouldn’t have been on their own evidence for insanity.10

But Jeremiah’s insistence that his uncle had been insane and the courts’ willingness to hear him out did not surprise a reporter from the abolitionist newspaper The National Era. Just the fact that John’s will was “not only liberating his slaves, but parceling his lands among them” would be “satisfactory evidence of insanity by the slaveholders of that intensely pro-slavery county.”11

As such, the case dragged on for years and some questionable legal strategies appeared. In 1853, Jeremiah and his lawyers pulled an unexpected move. Jeremiah petitioned for—and got—an injunction back in Prince George’s. This order halted trials and prevented any of the slaves from taking legal action until John Townshend’s will was settled and his property (including all of them) was distributed among his heirs—of which Jeremiah was the main benefactor.

in 1881. [Source: MD Archives]

With an injunction, Jeremiah could force all 70 slaves into a single lawsuit which he would litigate just once—confident he would win—and be done with. Not only that, but he would retake his home court advantage: the injunction would bring everyone back to Prince George’s County—the same setting judges already ruled could not give the slaves a fair trial. Moreover, the case would not go to a normal court, but an equity court. Equity courts operated separately from courts of law, operated on the concept of fairness rather than precedent, and took a more flexible approach to an individual’s claims. Essentially, if Jeremiah could get into a sympathetic equity court, the laws the slaves were invoking wouldn’t matter so much. It was a very modern, clever, and questionable piece of legal contortionism.

With the case again before the Court of Appeals, Alexander protested on behalf of Jerry and Anthony that it was preposterous for Jeremiah to “seek in such bill, to compel the negroes to litigate their rights to freedom… against the person unlawfully holding them in servitude.”12 Besides, a court in Prince George’s had no authority to halt proceedings in another county.

Jeremiah in turn bade the judges consider the “great number” of slaves petitioning their freedom and that without the injunction, he would be subject to “enormous and ruinous costs from the multiplicity of suits, and be unjustly and greatly harassed.”13 This argument omitted the convenient fact that turning the case over to an equity court would turn his legal battle into a war of attrition: one he could weather, but Jerry, Anthony, and the other slaves could not.

Again, the judges were unimpressed. They ruled in a curt opinion that the petition for freedom would be heard by the same tribunal that would decide on John Townshend’s sanity (which still hadn’t been resolved!). They also saw right through Jeremiah’s strategy, reminding him that “there are a number of negroes, whose freedom depends upon the result, all of whom, individually and separately, are entitled to this right of challenge.”14

After nearly a decade in court, the question of John Townshend’s mental state was finally settled in 1856. In the last trial, Jeremiah set out to prove that his father had been insane when he had written his deeds of manumission. With worrying efficiency, he produced several witnesses who testified to their experiences with John from 1815 to 1846. On behalf of the slaves, whose freedom hung in the balance, Thomas Alexander objected to the witnesses’ testimony, but it was admitted as evidence, sliding the scales in Jeremiah’s favor.

Jeremiah had also managed to get Dr. John Fonerden, the director of Maryland’s Hospital for the Insane, to the stand. His attorneys asked the doctor to give his opinion on John’s sanity, judging by the previous testimony and the “declarations of John Townshend as to his personal intercourse with God.”15

Alexander vehemently objected to this question because it was “calculated and designed to give to the defendant the benefit of the opinion to be expressed by the witness, without any statement or exhibition of the facts.”16 Unfortunately, he was overruled and Dr. Fonerden’s answer—though it isn’t recorded—was not flattering to John Townshend. The court found John Townshend insane and the deeds of manumission invalid.

The slaves’ and Alexander’s last hope was that the Appeals Court would deem this evidence inadmissible and reverse the judgement, but that was not to be. The witnesses’ evidence, the court declared, was admissible, though it noted that the way Jeremiah’s legal team had introduced Dr. Fonerden had toed the line of unacceptable. It was legal to ask an expert “his opinion upon a state of facts, hypothetically put, based upon the evidence.” But the way in which this question was asked “transfer[ed] the functions of the jury to the witness, and would permit him to decide upon the very fact at issue, and thus to control the verdict of the jury.”17

Seeing Jeremiah get berated by the justices was a tiny consolation, but not nearly enough, after losing a nearly decade-long battle.

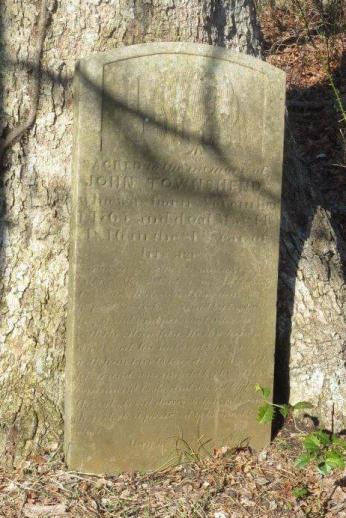

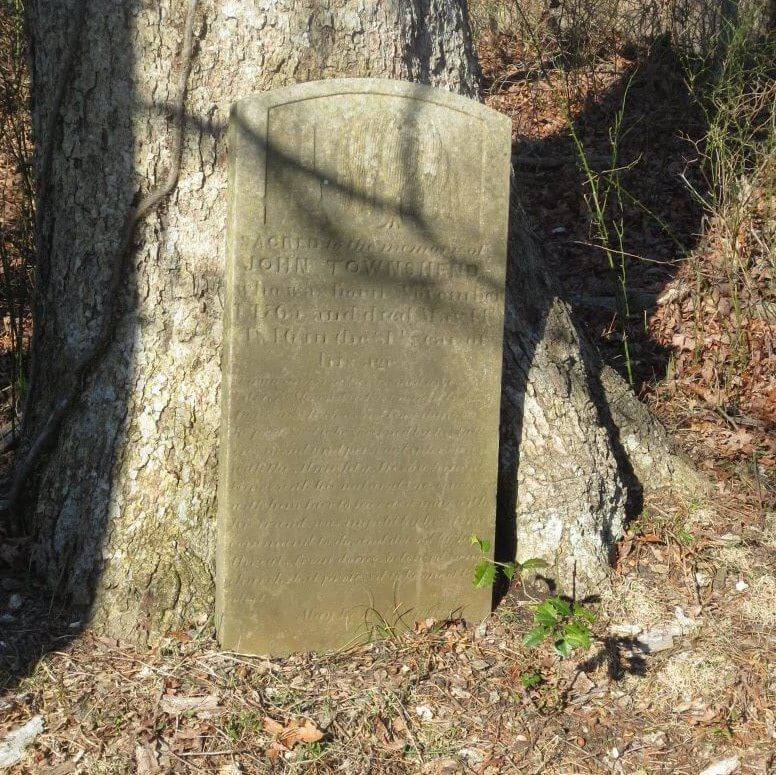

With all their legal options exhausted, Jerry, Anthony, and the other slaves had to give in. They were forced to wait another eight years for freedom, when Maryland finally rewrote its constitution to abolish slavery in 1864. Besides that, almost nothing is known about them. In 1857, Jeremiah advertised for a sale of “eighty valuable” slaves.18 One woman named Henrietta was buried in the Townshend family cemetery.19

Townshend v. Townshend continues to be cited and taught in law courses today, mostly as a short anecdote explaining the first use of insane delusion in the United States. The seventy slaves who fought for and were ultimately denied their freedom are rarely mentioned, though there are now efforts to change that. They continue to exist whenever the Townshend case is cited: phantoms of context that float just beyond the law-school summary.

slave is buried in an unmarked grave there.

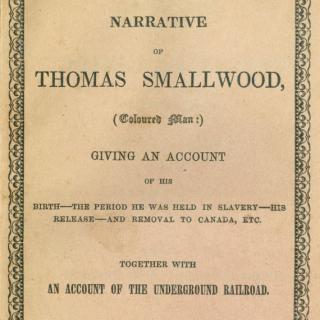

[Source: MD Register of Historic Places]

Footnotes

- 1

Legal, US. “Insane Delusion Law and Legal Definition.” USLegal, Inc. Accessed June 29, 2023.

- 2

Gallacher, Ian (2001) "Learning More Than Law from Maryland Decisions," University of Baltimore Law Forum: Vol. 32: No. 1, Article 2.

- 3 MD ch. 67 of 1796 acts

- 4

MD State Archives. “Thomas Fielder Bowie,” 2003.

- 5 Alexander protested the improper regression to the Appeals Court in 1852, pointing out that the 1849 Act specifically provided for cases where “a fair and impartial trial cannot be had” in the county of residence. Bowie argued that the law was unconstitutional and—even if it weren’t—it didn’t apply to Jerry and Anthony. This was because the 1849 Act covered any “suit or action at law.” As unusually generous as that wording was, it did no good: Maryland slaves could not file suits or actions at law. It was a suggestion with the potential to cripple the case. If Jerry and Anthony’s petition was in a courtroom at all, and they were slaves, then it couldn’t be a suit. If it wasn’t a suit, then the Act could not be invoked. The case would stay in Prince George’s unsympathetic milieu.

- 6

Caselaw Access Project. “Jerry v. Townshend, 2 Md. 274 (1852).” Accessed June 23, 2023.

- 7

Caselaw Access Project. “Townshend v. Townshend, 7 Gill 10 (1848).” Accessed June 23, 2023.

- 8

Caselaw Access Project. “Townshend v. Townshend, 7 Gill 10 (1848).” Accessed June 23, 2023.

- 9 Gill, Richard Wordsworth. Reports of Cases Argued and Determined in the Court of Appeals of Maryland. Vol. 7. Geo. Johnston, printer, 1852.

- 10 Switala, William J., p. 70, Underground Railroad in Delaware, Maryland, and West Virginia

- 11

Noble, L.P. “Baltimore Correspondence.” The National Era, November 25, 1847.

- 12

Caselaw Access Project. “Townshend v. Townshend, 5 Gill 287 (1853).” Accessed June 23, 2023.

- 13

Caselaw Access Project. “Townshend v. Townshend, 5 Gill 287 (1853).” Accessed June 23, 2023.

- 14

Caselaw Access Project. “Townshend v. Townshend, 5 Gill 287 (1853).” Accessed June 23, 2023.

- 15

Caselaw Access Project. “Jerry v. Townshend, 9 Md. 145 (1856).” Accessed June 23, 2023.

- 16

Caselaw Access Project. “Jerry v. Townshend, 9 Md. 145 (1856).” Accessed June 23, 2023.

- 17

Caselaw Access Project. “Jerry v. Townshend, 9 Md. 145 (1856).” Accessed June 23, 2023.

- 18 St. Mary's beacon. (Leonard Town, Md.), 17 Dec. 1857. Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress.

- 19

Maryland Historical Trust, Maryland Inventory of Historic Properties: McKendree Methodist church site and cemetery, Inventory No. PG:85A-20, Maryland: 2015.

![Sketch of the mythical fuan by Pearson Scott Foresman. [Source: Wikipedia]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2023-10/Goatman_Wikipedia_Faun_2_%28PSF%29.png?h=64a074ff&itok=C9Qh-PE1)