The 1868 Mayoral Election, African-American Vote, and Riots That Followed

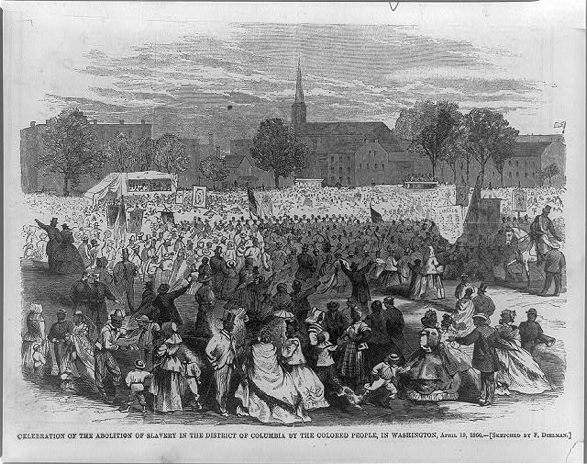

On January 8, 1867, Congress passed the District of Columbia Suffrage Bill, granting African-American men the right to vote for the first time in U.S. history. This bill, which became law when the new Republican majority in Congress overrode President Johnson’s veto, allowed African-American men in D.C. to vote months before the 1867 Reconstruction Acts granted African-Americans in the South to vote, and three years before the passage of the 15th amendment granted all men the right.[1]

As black men in the District of Columbia prepared to cast their ballots for the first time, the suffrage bill was still it its “trial stage” in the minds of many – even many Republicans. The Evening Star, a moderate Republican newspaper, dismissed the bill as “the opening of a war on the rights of the white laboring men of the whole Union.”[1] Moderate Republicans feared the bill would “Africanize the city” and make D.C. into a “negro Utopia.”[2] The political benefits ultimately outweighed such concerns, however, as it was virtually guaranteed that the black vote would support the Republican party.

D.C.’s black community was ecstatic. As The Baltimore Sun reported in a “Letter from Washington” in May 1867, a few weeks prior to the city’s municipal elections:

“The colored people have turned out in force to have their names added to the list and they block up the way continually. In some instances, colored voters have appeared for registration knowing that their names were already recorded. This was done simply for the purpose of killing time.”[3]

Black men were an impressive fifty percent of registered voters despite being only thirty percent of D.C.’s population.[4]

This was certainly an exciting start, but the drama surrounding the black vote skyrocketed a year later in June 1868. And it makes sense; the stakes were notably higher, as the two candidates for Washington’s new mayor promised vastly different futures for the city.

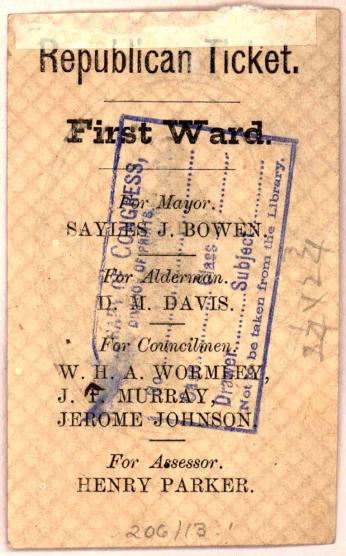

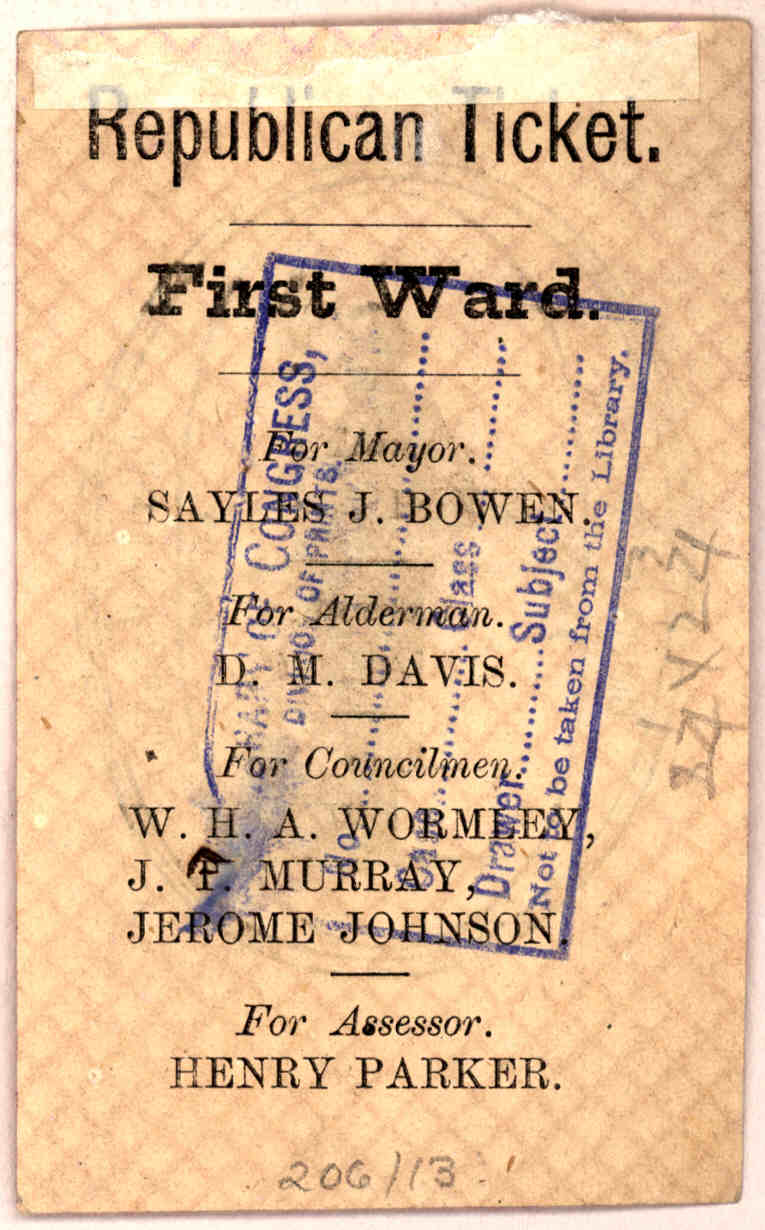

The Democratic nominee, John T. Given, was a wealthy and conservative businessman, whom some called the “White Man’s Candidate.”[5] Given obviously appealed to D.C.’s wealthy, white community, and he was also notably less supportive of African-American rights than his opponent. Republicans nominated Sayles J. Bowen, a New York native and government postmaster. Bowen was, according to many newspapers at the time, “the Radical.”[6]

The Evening Star’s assessment of the election noted Bowen’s “various efforts…in behalf of the coloured race,” including “in the cause of education; in enabling colored persons to testify in courts; in securing justice to colored men by the police; in procuring suffrage for colored men…”[7] It should be noted that despite all the talk, Bowen was accused of “failing to appoint coloured letter carriers” while postmaster,[8] but to most Democrats, Bowen was still too supportive of African-Americans.

On June 2nd, 1868, the city brimmed with anticipation and excitement, with “Given and Bowen bonfires blaz[ing] along nearly every street” in Washington.[9] Two crowds of Democrats and Republicans marched along “D street to 8th and then to 9th,” cheering for their candidate and booing the other crowd.[9] Even before the result was announced, drama ensued over the counting process. The council numbering the votes was Democratic by a small majority, and some worried about potential foul play. As The National Intelligencer reported, “It is to be hoped they will perform their duty, as there may have been mistakes made by the judges.”[10]

By late evening, the Council had finished counting; but the conflict of the night was far from over. Bowen won over Given by a narrow 83 votes. The Evening Star reported, “In consequence for the closeness of the vote for Mayor, there was great uncertainty as to the result last night, and both parties claimed the election of their candidate.”[9]

As a procession of Republican citizens serenaded the new Mayor Bowen, opposers attacked, “firing into its ranks a volley of stones.”[9] The “assault was returned in kind, not during the procession, but after.”[9]

Although the uproar was in large part due to the close margin of votes, newspapers quickly racialized the conflict, presumably because the African-American vote was a new and central aspect of the election.

A Democratic newspaper, The Georgetown Courier, went so far as to remark: “The races are now pitted against each other in deadly animosity…very little added excitement is required to drench the streets of the capital with human blood.”[1] The Baltimore Sun byline from 1868 wasn’t quite as dramatic, but it still noted the “SERIOUS RIOT IN WASHINGTON” as being one comprised of “Difficulties between Blacks and Whites.”[11]

According to The Baltimore Sun, a large crowd gathered outside of Bowen’s house to hear his victory speech, and “disturbances” soon grew out of the excitement. Most of the violence concentrated around Bowen’s residence and was perpetrated by Bowen’s supporters. The Sun reported:

“On the corner of Seventh and H streets, a young man...was knocked down and cut so badly with a razor that his recovery is somewhat doubtful…Smith’s restaurant, corner of Eleventh and F streets, was entered by force, the barkeeper knocked down and the money drawer robbed. The residence of Captain Daniels, corner of Thirteenth street and New York avenue, was assaulted without provocation.”[11]

It’s likely the “mob” was comprised of Bowen’s supporters at large rather than African-American men alone, but news coverage honed in on acts perpetrated by black men. The Baltimore Sun took note of the “Many of the colored men in the procession” to support Bowen, and reported that some of these “colored men entered restaurants and demanded drinks. Upon being informed that the restaurants were kept for white customers, they threatened to ‘clean out’ the house and several restaurant keepers were compelled to close their businesses."[11] The Sun continued, “It was a fearful sight to see this mob of people surging through the streets offering insult to women and children, and threatening all with vengeance.”[11]

Despite how news outlets portrayed the election, D.C. woke up to a new mayor in power, and the African-American vote played a major part in getting him there. Black voters had aptly used their newfound voting power to elect a candidate who seemed most likely to advance their political and economic clout.

Earlier, Bowen had promised to “dispense corporation favors without regard to race or color.”[12] As mayor he was true to this, appointing black people to thirty percent of the positions in his administration.[1] Bowen was also faithful in attempting to put an end to racial separation in venues of recreation and entertainment.[13]

By 1869, it seemed that Washington was well on its way to embracing a biracial democracy.[1] Unfortunately, Bowen’s administration ultimately didn’t fulfill all its promises. Bowen opposed integration of D.C.’s schools, and black voters also accused Bowen of favoring Irish Republicans over Black Republicans.[1] The real problem, though, was Bowen’s poor financial decisions. Within the year, Bowen had drowned D.C. in debt. What’s worse, Bowen’s failed administration fueled the fire of Conservative leaders who attempted to eliminate black suffrage.[1] Even Republicans turned against black voters, saying black voters had used their newfound power unwisely and had chosen the wrong candidate.[1]

Partially in an effort to curb the power of the African-American vote, Democrats and Republicans alike lobbied Congress for “a single territorial government.”[14] This new plan, passed in February 1871, placed local government largely out of the hands of D.C. voters.[14] Instead of an elected mayor and council, the District would have a territorial governor appointed by the President with a legislature that had an appointed upper house and an elected lower house. Alexander Robey Shepherd, who led the Board of Public Works before being appointed as governor in 1873, used territorial government to implement sweeping changes. In a very long story turned short, Shepherd helped modernize the city, but racked up tremendous debt in the process. After just three years, Congress decided to pull the plug on territorial government and “revert to a presidentially appointed board of three commissioners to manage the city.”[14] Originally passed in June 1874, the system was made permanent by Congress in 1878. This brought the final blow for D.C. voters – both white and black. District men would not vote again for nearly a hundred years.[15]

Thus, although a mayoral election may seem like a minor event in history, it’s far more complex of a story than one might initially believe. The election’s aftermath and the chain of events it provoked certainly demonstrate the power of the black vote, but it also illustrates just how tenuous both racial and political dynamics in Washington were at the time.

Footnotes

- a, b, c, d, e, f, g, h Chris Myers Asch and George Derek Musgrove. Chocolate City: A History of Race and Democracy in the Nation’s Capital, (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2017), 150

- ^ Ibid, 143.

- ^ LETTER FROM WASHINGTON Correspondence of the Baltimore Sun, The Sun (1837-1994); May 31, 1867; ProQuest Historical Newspapers: The Baltimore Sun pg. 4

- ^ Chris Myers Asch and George Derek Musgrove. Chocolate City: A History of Race and Democracy in the Nation’s Capital, (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2017), 147

- ^ Christopher Young, “The Mayoral Race 150 Years Ago Was As Contentious As This Year’s Primary Is Sleepy,” DCIst, June 19, 2018. https://dcist.com/story/18/06/19/sayles-given-dc-election-196

- ^ Important Patent Decision--Local Politics--The Mayoralty Election of ... Correspondence of the Baltimore Sun, The Sun (1837-1994); Apr 27, 1868; ProQuest Historical Newspapers: The Baltimore Sun pg.

- ^ Evening star. [volume] (Washington, D.C.), 07 May 1868. Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress. <https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn83045462/1868-05-07/ed-1/seq-…;

- ^ Alexandria gazette. [volume] (Alexandria, D.C.), 22 June 1868. Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress. <https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn85025007/1868-06-22/ed-1/seq-…;

- a, b, c, d, e Evening star. [volume] (Washington, D.C.), 02 June 1868. Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress. <https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn83045462/1868-06-02/ed-1/seq-…;

- ^ William Bensing Webb and John Wooldridge, Centennial History of the City of Washington, D. C. With Full Outline of the Natural Advantages, Accounts of the Indian Tribes, Selection of the Site, Founding of the City ... to the Present Time, United Brethren Publishing House, Dayton, 1892.

- a, b, c, d SERIOUS RIOT IN WASHINGTON: DIFFICULTIES BETWEEN BLACKS AND ... Correspondence of the Baltimore Sun, The Sun (1837-1994); Jun 4, 1868; ProQuest Historical Newspapers: The Baltimore Sun pg. 1

- ^ TELEGRAPH NEWS The Sun (1837-1994); May 9, 1868; ProQuest Historical Newspapers: The Baltimore Sun pg. 1

- ^ Chris Elzey and David K. Wiggins, DC Sports: Nation’s Capital at Play, University of Arkansas Press, 2015

- a, b, c Chris Myers Asch and George Derek Musgrove. Chocolate City: A History of Race and Democracy in the Nation’s Capital, (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2017), 160

- ^ Chris Myers Asch and George Derek Musgrove. Chocolate City: A History of Race and Democracy in the Nation’s Capital, (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2017), 166

![Sketch of the mythical fuan by Pearson Scott Foresman. [Source: Wikipedia]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2023-10/Goatman_Wikipedia_Faun_2_%28PSF%29.png?h=64a074ff&itok=C9Qh-PE1)