Dolley Madison, the Queen of Washington

In Washington’s early years, when the city was just a handful of houses and offices, society revolved around the President and his administration. In fact, most of the nicest homes were clustered around the White House and Lafayette Square — quite literally, a social circle.

The President and his wife hosted elaborate parties for their neighbors: politicians, politicians’ wives, ambassadors, judges, journalists, and full-time residents from prominent local families. At one such party, held on New Year’s Day in 1847, the Daily Union reported that “ladies and gentlemen ... poured into the Executive House, and filled the east room and the other reception apartments.”[1] For President James Polk, the large turnout must have been a triumph; it indicated that he was a well-liked politician and host. But, interestingly, the Daily Union columnist adds that the President’s party eventually moved elsewhere. “It gives us pleasure to add that many a visitor waited upon Mrs. Madison,” they wrote, “to pay his respects to one whose name is never pronounced in Washington without veneration and regard.”[2] Some papers, like the Boston Daily Atlas, even asserted that “Mrs. Madison was more generally visited than the President.”[3] Even the President couldn’t compete with the Queen of Washington.

Mrs. Madison was, of course, Dolley Madison — widow of James Madison, the fourth President. Today she is widely remembered for her heroism during the War of 1812, when she saved a portrait of George Washington from being taken and burned by British invaders. But during her lifetime, she was best known as a prominent socialite, hostess, and politician in her own right — one of the country’s first celebrity personalities. The Daily Union referred to her as “the center of general attraction and the object of general admiration” in Washington.[4] To others, she was the “Queen of Washington” or the “Queen of America.” By the 1840s, when she returned to the city after retirement in Virginia, she was also a living legend — an elegant Presidential widow, a relic of the founding generation, holding court in the city she helped create.

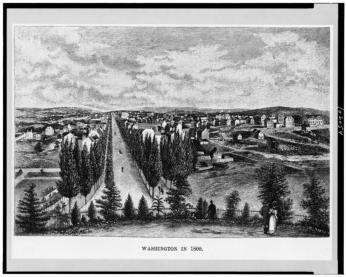

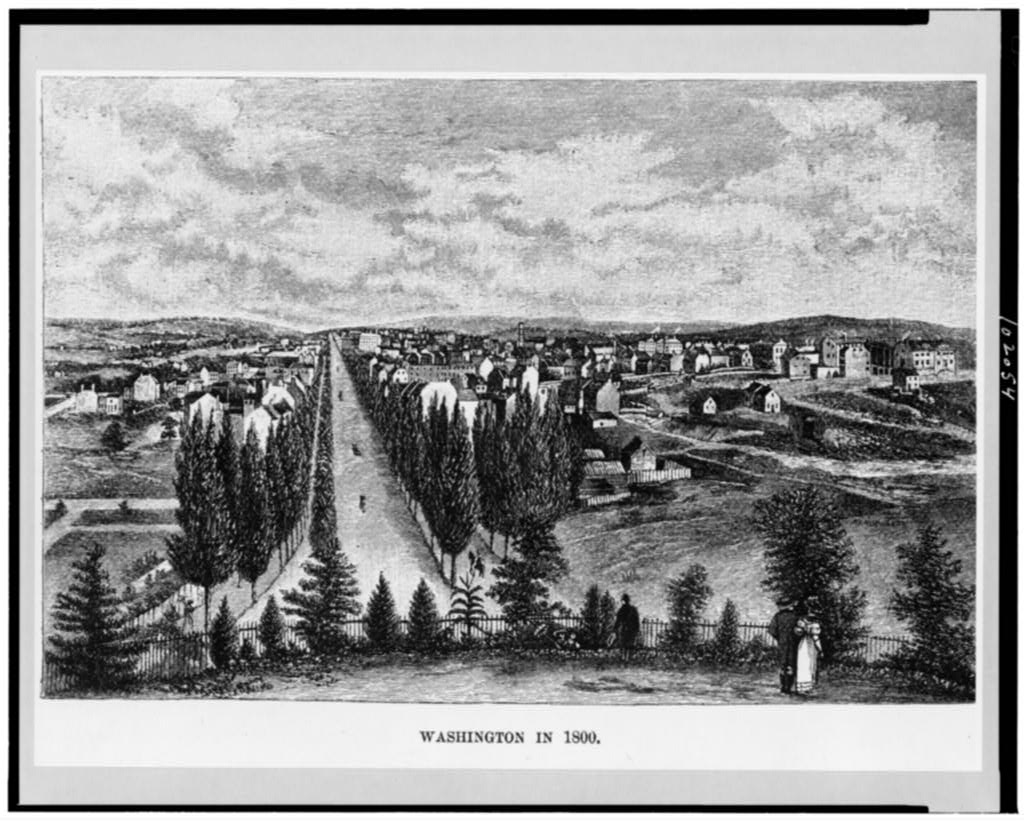

Dolley Madison first came to Washington in 1801, when President Thomas Jefferson chose James Madison as his Secretary of State. These were the earliest years of the city when the President’s house was brand new and Congress worked in an unfinished Capitol building. Despite living in this perpetual construction site, Dolley was determined to make her new home admirable and refined. The Madisons moved into a townhouse on F Street NW, which Dolley decorated with expensive, fashionable furniture. She also bedecked herself in sumptuous clothes that became her trademark: velvet gowns with long trains, pearl jewelry, and even turbans of “velvet and white satin (from Paris) with ... bird of paradise feathers.”[5] Soon, the Madisons were known for hosting elaborate, lively dinner parties that far eclipsed any entertainments at the White House. They were often referred to as “squeezes” or “crushes,” since turnout was great but space was limited. Margaret Baynard Smith, a journalist, and friend of Dolley’s, described an evening at the Madisons’ in a letter to a friend:

“The room was so terribly crowded ... and poor Mrs. Madison was almost pressed to death, for every one crowded round her, those behind pressing on those before, and peeping over their shoulders to have a peep of her, and those who were so fortunate as to get near enough to speak to her were happy indeed.”[6]

As much as she probably enjoyed the attention, Dolley used her parties to achieve greater goals. For one thing, James owed his growing popularity to his wife’s charisma. The Madisons were a famously mismatched couple but made a powerful team. Though serving in a very public role, James tended to be quiet and resolute in social situations — Smith reported he “seemed spiritless and exhausted” at his own party.[7] Dolley, by contrast, acted with an “unassuming dignity, sweetness, [and] grace” that compensated for her husband’s shyness.[8] But even as she furthered her husband’s career in Washington, Dolley also tried to further the new capital’s reputation. Establishing a respectable society in Washington and showing off American hospitality to foreign ambassadors was Dolley’s greatest mission. It clearly worked, because everyone agreed that Dolley was the closest thing the United States had to a queen. She even served as the country’s official hostess when the widower Jefferson required it. “She really in manners and appearance, answered all my ideas of royalty,” Smith wrote.[9] Senator Henry Clay of Kentucky once remarked that “everybody loves Mrs. Madison.” Without missing a beat, Dolley smiled and replied, “That’s because Mrs. Madison loves everybody.”[10]

When James became President in 1809, the famous gatherings moved to the White House. Though the President’s wife had no official role or title, Dolley brought her already-established fame to her new position. As the country moved closer to war, she even invited her husband’s political enemies to parties, where she encouraged polite conversation and debate. But, really, even the war didn’t stop Dolley — on that famous night in August 1814, when British soldiers marched on Washington and burned as they went, Dolley had laid out an impressive dinner for 40 people. After she finally fled the city, the soldiers “ate up the very dinner, and drank the wines” before destroying the house.[11]

The Madison presidency ended in 1817. After sixteen years in the capital, James and Dolley retired to their Virginia plantation home, Montpellier. For a while, it was the idyllic life. James organized his many papers — writings and insights on the Constitutional Convention and his time in office — and helped his neighbor, Jefferson, establish the University of Virginia. Dolley still entertained, just on a smaller scale. But her life took a dark, dramatic turn in 1836 when the 85-year-old James died. The Madisons were not extremely wealthy, so James expected that the publication and sale of his papers would bring much-needed income for his widow. His will also promised bequests to several charities, including the University. Unfortunately for Dolley, no one was initially interested in buying the papers. Wanting to honor her husband’s final wishes, she made his requested donations from her own funds. She also reluctantly funded the lifestyle of her son, Payne, who was a notorious gambler and alcoholic. By the end of the year, she was virtually penniless.

Wishing to forget her sadness and financial troubles, Dolley returned to Washington in 1839. She moved into her pale-yellow townhouse on Lafayette Square (which has had many uses over the years). Her biographer Catherine Allgor writes, from the moment of her arrival, Dolley “embarked on a social merry-go-round.”[12] Invitations were many — everyone wanted to see her. Since she had been away, Dolley had become something like a mythical figure in Washington society. No one had quite replaced her as the city’s universally beloved hostess. She was also one of the last survivors of the first political generation — someone who actually knew George Washington, Jefferson, and Alexander Hamilton and could tell personal stories about them. Dolley added to her new mystique by wearing the same velvet gowns and turbans that, though out of style, had once been her signature look. It was lucky for her because she couldn’t actually afford any new clothes.[13]

Dolley’s poverty was a well-known secret in Washington. Those who paid a call to the Lafayette Square townhouse often left small amounts of money behind, hidden away for their hostess to find later.[14] Evidently, everyone felt it was their duty to support a national treasure. The sympathy eventually persuaded Congress to offer Dolley money for a portion of her husband’s papers, but it was not nearly what she hoped for — and not enough to cover the family (especially her son’s) debts. In 1844, desperation forced her to sell her husband’s family home, Montpelier. The estate included the house, furniture, several acres of land, and perhaps the family’s most profitable asset: slaves. Dolley made some effort to sell her slaves to masters who would eventually free them; Paul Jennings, who had been devoted to James, was sold to and later freed by Congressman Daniel Webster. But ultimately, whatever personal feelings she had towards them, the slaves were a source of much-needed revenue. And, despite the injustices inflicted upon them, some were also sources of comfort. As the biographer Allgor notes, Dolley experienced one of the “ironies of slaveholding life”: that, as her close family died or abandoned her, the people who knew her best were once her property.[15] Jennings later wrote a memoir of his time with the Madisons — the first White House memoir ever published — which describes visits to his former mistress:

“In the last days of her life, before Congress purchased her husband’s papers, she was in a state of absolute poverty, and I think sometimes suffered for the necessities of life. While I was a servant to Mr. Webster, he often sent me to her with a market-basket full of provisions, and told me whenever I saw anything in the house that I thought she was in need of, to take it to her. I often did this and occasionally gave her small sums from my own pocket, though I had years before bought my freedom of her.”[16]

But even though she struggled with finances, Dolley still put on a good show for Washington. She could not always entertain at her own home but received invitations to all the best parties, including those at the White House. All of the Presidents knew her and valued her opinions; their wives always received (perhaps unwanted) advice on entertaining. Dolley even played matchmaker for the first families — at one of her own parties, she introduced Abraham Van Buren, President Martan Van Buren's son, to his future wife.

Congress also honored Dolley, even if they still refused to purchase the full allotment of her husband’s papers. On January 8, 1844, the House of Representatives voted unanimously to allow Dolley her own seat on the House floor. She often attended debates, seated in the gallery with other spectators; now she could be at the center of the action. It is an honor seldom given, even today, and Dolley was quite aware of its weight. “Permit me to thank you, gentleman,” she wrote them, “for the great gratification you have this day conferred upon me by the delivery the favor from that honorable body, allowing me a seat within its hall.”[17] She is still one of the few non-members to have her own seat there.

As if that could be topped, the honors kept coming. Later in 1844, she attended a demonstration of Samuel Morse’s new telegraph machine at the Capitol. The inventor chose her to send the first ever private telegram: a message to a friend in Baltimore. She also served in the Monument Society, the group dedicated to building a monument to George Washington. Fittingly, she was charged with raising awareness and collecting donations for the project.[18] In 1848, she presided over the laying of the Monument’s cornerstone.

And then, a personal victory: late in 1848, Congress agreed to buy the rest of James’s papers. Out of respect for Dolley, they paid more than their initial offer, but it was still not the amount she expected. The majority of it went to creditors since Dolley had charged her living expenses for years, and so did not provide her with any regular funds. But Congress did her one service: they put the money in a trust, so her lecherous son could not touch it and further impoverish his mother. In the end, though, it was all too late. Dolley’s health was failing.

Mrs. Madison died in her Lafayette Square home on July 12, 1849, aged eighty-one. In Washington, it was breaking news. “Just as we are preparing to go to press, we hear with profound grief of the death, in this city, of Mrs. D. Madison,” the Daily Union reported. “This greatly venerated, beloved, and celebrated lady ... breathed her last, at a quarter past 10 o’clock, last night.”[19] The city went into full mourning. President Zachary Taylor declared all government offices should close for the funeral so members of Congress and the cabinet could attend. In every way, it resembled a state funeral — it was certainly the largest held in Washington at the time so that even Dolley’s funeral was a “squeeze.” St. John’s Episcopal Church, her preferred local church, was so full that crowds spilled outside during her memorial service.[20] Afterward, a procession of Congressmen and soldiers escorted Dolley’s coffin to the Congressional Cemetery, where she was temporarily kept before her formal internment at Montpellier. Crowds of locals had the chance to say goodbye to their Queen, a staple of the city since it was nothing but a few small buildings.

According to legend, President Zachary Taylor was asked to give a eulogy at Dolley’s funeral. It was only fitting since she knew so many politicians — including the first twelve presidents— personally. In his speech, Taylor vowed Dolley would never be forgotten, “because she was truly our first lady for a half-century.”[21] Obviously, the title stuck.

Footnotes

- ^ The Daily Union, January 1, 1847.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ The Boston Daily Atlas, January 6, 1847.

- ^ The Daily Union, July 14, 1849.

- ^ Margaret Baynard Smith, The First Forty Years of Washington Society, ed. Gaillard Hunt (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1906), 62.

- ^ Margaret Baynard Smith, 61.

- ^ Margaret Baynard Smith, 63.

- ^ Margaret Baynard Smith, 62.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Catherine Allgor, A Perfect Union: Dolley Madison and the Creation of the American Nation (New York: Henry Holt and Company, 2006), 232.

- ^ Paul Jennings, A Colored Man’s Reminisces of James Madison (Brookyln: George C. Beadle, 1865), 13.

- ^ Allgor, 380.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Cormac O’Brien, Secret Lives of the First Ladies: What Your Teachers Never Told You About the Women of the White House (Philadelphia: Quirk Books, 2009), 31.

- ^ Allgor, 396.

- ^ Jennings, 14.

- ^ “The Rare Privilege of the House Floor Awarded to Former First Lady Dolley Madison,” History, Art & Archives: The House of Representatives, https://history.house.gov/Historical-Highlights/1800-1850/The-rare-priv…

- ^ Catherine Allgor, “The Politics of Love,” The National Endowment for the Humanities, https://www.neh.gov/humanities/2010/januaryfebruary/feature/the-politic…

- ^ The Daily Union, July 13, 1849.

- ^ Allgor, 398.

- ^ Amy Pastan, First Ladies (New York: Dorling Kindersley, 2001), 13.

![Sketch of the mythical fuan by Pearson Scott Foresman. [Source: Wikipedia]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2023-10/Goatman_Wikipedia_Faun_2_%28PSF%29.png?h=64a074ff&itok=C9Qh-PE1)