Skeletons in the Closet: the Smithsonian’s Native American Remains and the NMAI

The Smithsonian museums attract millions of D.C. locals and tourists alike every year, but in the late 1980s, the Institution found its reputation at risk. As Smithsonian spokeswoman Madeline Jacobs described in October of 1989, “The calls and letters” during that period were “like a flood."[1] "Even important topics like our divestment from South Africa didn't get this much attention,” Jacobs told The Washington Post.[1]

What sparked the uproar? In 1989, the Smithsonian reportedly held 35,000 skeletal remains of Indigenous peoples, 18,500 of which were Native American remains.[2]

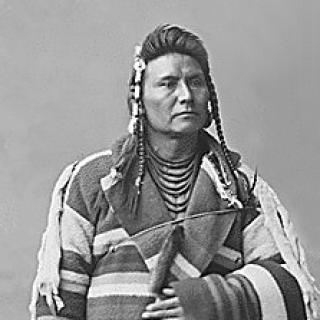

Native Americans had raised issue with museum possession of Native artifacts as early as 1978, but a Cheyenne tour of the Smithsonian in 1986 is what really got the ball rolling.[3] Northern-Cheyenne chiefs visited Washington D.C. and toured the Smithsonian’s Cheyenne collection at the National Museum of Natural History. As Clara Spotted Elk, a Northern-Cheyenne woman working on Capitol Hill, later recalled:

We were walking out, and we saw [the] huge ceilings in the room, with rows upon rows of drawers. Someone remarked that there must be a lot of Indian stuff in those drawers. Quite casually, a curator with us said, ‘Oh, this is where we keep the skeletal remains,’ and he told us how many -- 18,500. Everyone was shocked.[4]

They weren’t the first Native Americans to learn of this fact, but they were able to take unique action: Clara Spotted Elk served as legislative assistant to Democratic Senator John Melcher, and she immediately escorted the chiefs directly to Melcher’s office. “I told him of my concern,” recalled Chief Tallbull, “the concern of the Indian people, and he said ‘I’ll do what I can.,’"[5]

By 1987, Senator Melcher (D-MT) introduced a bill that sparked an “emotional Congressional debate.”[6] The bill stated that human remains of American Indians and their funerary objects were to be repatriated to Native Americans if found on federal lands. Senator Daniel Inouye (D.-HI), then chairman of the Senate Indian Affairs Committee, scheduled a hearing of Melcher’s bill.[6] Robert McCormick Adams, Jr., Smithsonian Secretary, confirmed at the hearing that “the Smithsonian had 18,500 human remains of Native peoples (American Indians, Alaska Natives and Native Hawaiians) in its collections.”[6]

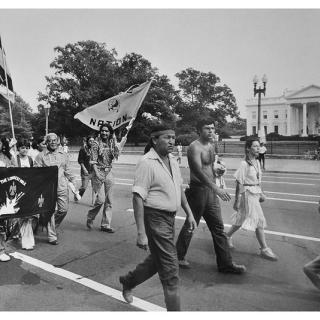

For Native American activists like Suzan Shown Harjo, Executive Director of the National Congress of American Indians, the hearing marked a turning point. “He was not being dismissive of human remains, but he was being insensitive,” remarked Harjo, in response to Adams’ testimony.[6] Though widely supported by Native peoples, Melcher’s bill “was strongly opposed by museum interests” who argued that the collection provided valuable scientific insights.[7] This opposition ultimately killed the bill, but extensive news coverage kept the debate simmering until 1989.

Dr. Douglas H. Ubelaker, curator of anthropology at the Smithsonian, advocated for the importance of the bones to Native history and scientific study. “No one could have predicted 10 years ago that we would be able to learn so much from chemical analysis of bone,” Ubelaker told The New York Times.[8] According to Ubelaker, the Native American activists “fail to realize the importance of collections of human remains in solving present-day problems affecting Indians.”[8] Denis W. Hastings, an anthropologist of the Omaha nation, also supported maintenance of the remains. Hastings argued, “it is very much in our interest to learn as much as possible about our past, especially now that the days have past when oral histories preserved our traditions.”[8]

Suzan Shown Harjo, however, argued that since the remains were taken forcibly as spoils of war and colonization, museum possession of them marked a vestige of “colonialism, dehumanization, and racism against [Native American] people.”[9] “Four thousand five hundred [remains] alone are from the Army Medical Museum, taken from people whose heads were taken at the turn of the century,” Harjo pointed out. Harjo also noted that for many, the issue was personal. The Smithsonian held some bones from her ancestors, Cheyenne people “whom…American soldiers massacred in November 1864 at Sand Creek, Colorado.”[9]

Activists also advocated for the bones’ religious significance. Curly Bear Wagner of the Blackfeet Nation remarked that “religious customs of many American Indian tribes hold that bodies must be returned to Mother Earth in order to continue their spiritual journey. Those spirits whose journeys are interrupted may become unsettled and malevolent.”[10] "Spiritually, they belong back on the reservation," explained Wagner. "Our people had no intention of letting them be dug up and taken to a museum in Washington, D.C. How would you like it if someone dug up your grandfather and moved him?"[10]

Despite anthropologists’ defense, Native American activism coupled with news coverage successfully mounted pressure on the Smithsonian Institution, and in September of 1989, the Smithsonian put forward a formal agreement to repatriate the skeletal remains of “thousands of American Indians to their tribes for reburial in their homelands.”[11]

Secretary Adams reacted to the agreement with mixed feelings. ''It is wonderful and inevitable….We do so with some regret, but everyone would acknowledge that when you face a collision between human rights and scientific study, then scientific values have to take second place. To do otherwise would suppress the record of violence against Indians in the westward movement.''[11]

In addition to the agreement, a panel comprised of Native Americans, anthropologists, and museum officials worked together to form recommendations for federal legislation to support the repatriation agreement.[12] In November of 1990, Congress passed the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act (NAGPRA).[13]

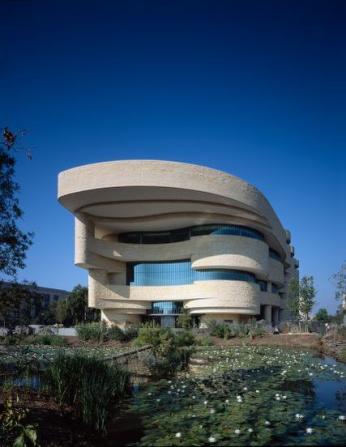

Repatriation was certainly a victory, but as Senator Inouye had observed in 1988, there was also the issue of “a city of monuments [Washington, D.C.]” having never established a “monument to Native peoples.”[6] Inouye sought to change this, introducing a bill in September of 1988 to that allowed the Smithsonian to share the resources of New York's Museum of the American Indian, as well as make space for a “National Museum of the American Indian” in Washington D.C.[14] The bill was passed by the House unanimously and by the Senate in November 1989.[15]

Patricia Zell, Senator Inouye’s staff director and chief counsel, remembered:

When it came time…to really focus on a ‘place’ for the museum [Inouye] literally looked down from his hideaway office balcony in the U.S. Capitol, saying, ‘What’s that blank spot down there?’ And we said, ‘What are you talking about?’ He said, ‘The one between the U.S. Botanical Garden and the Smithsonian’s National Air and Space Museum.'[6]

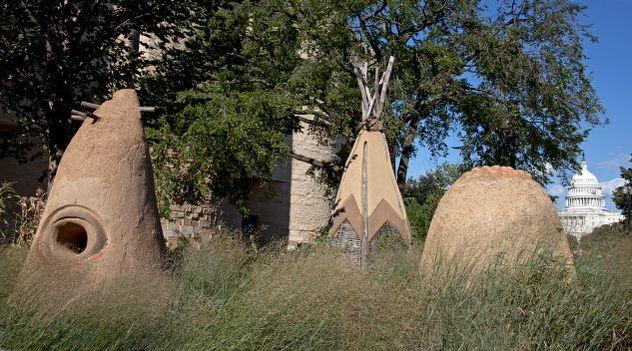

W. Richard West of the Cheyenne and Arapaho nations was appointed founding director of the museum in 1990. What followed was a long process of consultations with Native people, regarding questions of: “What do you expect from this place—what do you expect to see, what do you want in it, what’s it supposed to do?”[16] Based on this feedback, West sought to curate a museum that valued the many nations and Native “views, voices, and sets of eyes.”[16]

It would take almost 15 years, but on September 21, 2004, twenty-five thousand Native Americans representing over five hundred Indigenous nations gathered in Washington D.C. to witness the opening of the National Museum of the American Indian (NMAI).[17] The opening was “celebrated with a six-day First Americans Festival of music, dance, and storytelling.”[18]

W. Richard West gave remarks:

We have lived in these lands and sacred places for thousands of years. We thus are the original part of the cultural heritage of every person hearing these words today, whether you are Native or non-Native. We have felt the cruel and destructive edge of the colonialism that followed contact and lasted for hundreds of years. But, in our minds and in history, we are not its victims. As the Mohawks have counseled us, ‘It is hard to see the future with tears in your eyes.'[17]

Given the long fight it took to establish the NMAI, we shouldn’t overlook its rich resources and history. Like D.C.’s other museums, it has unfortunately closed its doors at the moment, but there are plenty of ways to take advantage of the city’s museums from home. Check out the NMAI website to access curated digital lessons, online accounts of museum exhibits, photographs of their collections’ artifacts, and much more.

Footnotes

- a, b Kara Swisher. The Washington Post, Washington, D.C., 03 Oct 1989: d05.

- ^ Indians Seek Burial of Smithsonian Skeletons: Scientists contend…” New York Times (1923-Current file); 08 Dec 1987, pg. C13

- ^ Peter H. Lewis, “Issue and Debate: Indian Bones,” New York Times, May 20, 1986, Section C, Page 3.

- ^ Repatriation Act Protects Native Burial Remains and Artifact,” Native American Rights Fund Review, 1991, https://www.narf.org/nill/documents/nlr/nlr16-1.pdf

- ^ C. Timothy McKeown, In the Small Scope of Conscience: The Struggle for National Repatriation Legislation, Tuscon: University of Arizona Press, 2013, p. 4.

- a, b, c, d, e, f Lis Hill, “A Warrior Chief Among Warriors: Remembering U.S. Senator Daniel K. Inouye,” Magazine of Smithsonian’s National Museum of the American Indian, 2014, https://www.americanindianmagazine.org/story/warrior-chief-among-warrio…

- ^ Repatriation Act Protects Native Burial Remains and Artifact,” Native American Rights Fund Review, 1991, https://www.narf.org/nill/documents/nlr/nlr16-1.pdf

- a, b, c Malcom W. Browne, “As Deadlines Near, Scientists Seek Data From Indian Bones: Scientists Seek Data in Indian Bones,” New York Times, 25 Sep 1990, pg. C1

- a, b Irvin Molotsky, “Smithsonian to Give Up Indian Remains,” The New York Times, 13 Sept 1989, pg. A14

- a, b Sara Lowen, “Bones of Contention,” Chicago Reader, 16 June 1988, https://www.chicagoreader.com/chicago/bones-of-contention/Content?oid=8…

- a, b Irvin Molotsky, “Smithsonian to Give Up Indian Remains,” The New York Times, 13 Sept 1989, pg. A14

- ^ Bill McAllister, “Panel Calls for Legislation To Return Indian Remains,” The Washington Post, 1 Mar 1990, pg. B2

- ^ “The Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act(NAGPRA),” Bureau of Reclamation, https://www.usbr.gov/nagpra/

- ^ Jacqueline Trescott, “Indian Museum Plan Scaled Back; Smithsonian Chief Lauds Inouye…” The Washington Post, 10 May 1988: e01.

- ^ Kara Swisher, “Indian Museum Bill Passes House; Vote Is Unanimous; Senate Approval Expected Today,” The Washington Post, 14 Nov 1989: c07.

- a, b W. Richard West, and Amanda J. Cobb. "Interview with W. Richard West, Director, National Museum of the American Indian." American Indian Quarterly 29, no. 3/4 (2005), 519

- a, b Amanda J. Cobb, "The National Museum of the American Indian: Sharing the Gift." American Indian Quarterly 29, no. 3/4 (2005): 361.

- ^ Edward Rothstein, “Museum With an American Indian Voice,” The New York Times, Sep 21, 2004, pg. E1

![Sketch of the mythical fuan by Pearson Scott Foresman. [Source: Wikipedia]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2023-10/Goatman_Wikipedia_Faun_2_%28PSF%29.png?h=64a074ff&itok=C9Qh-PE1)