From Defeated Foe to National Celebrity: Chief Joseph's Visit to D.C.

In the over 200 years since its founding, the nation’s capital has received no shortage of important visitors. Yet it’s not every day when the defeated foe of a war against the United States goes to D.C. to seek restitution. That’s just what happened in 1879, when Chief Joseph, leader of a band of Nez Perce Native Americans, came to Washington to plead with President Rutherford Hayes for his people’s right to return to their ancestral homeland.

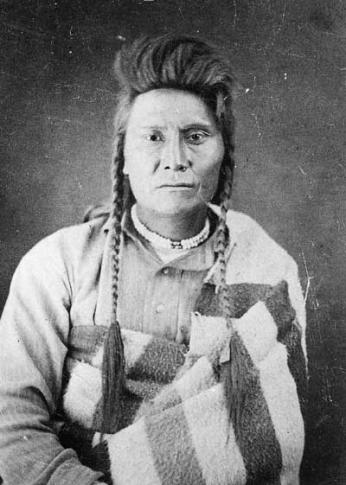

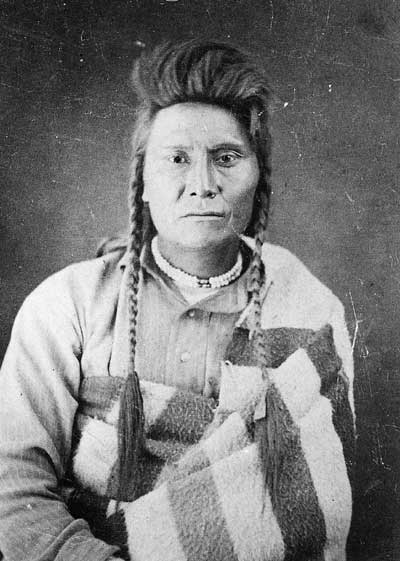

Hin-mah-too-yah-lat-kekt is just one of the several names he went by, but to whites, his name was Chief Joseph. He became a leader in a time of simmering tension.1 Joseph led a band of Nez Perce in their ancestral lands in Oregon’s Wallowa Valley. He became renowned for his passionate activism and peaceful resistance against the U.S. government’s attempt to resettle his band onto a reservation. He maintained friendly relations with the white Americans who settled traditional Nez Perce lands for farming and livestock, and never retaliated, even when his people suffered grave injustices at the hands of whites. But the westward expansion of settlers never stopped, and by the mid-1870s, confrontations between whites and Nez Perce had reached a fever pitch.2

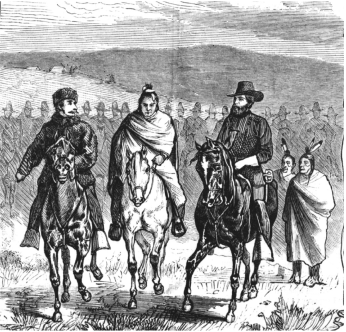

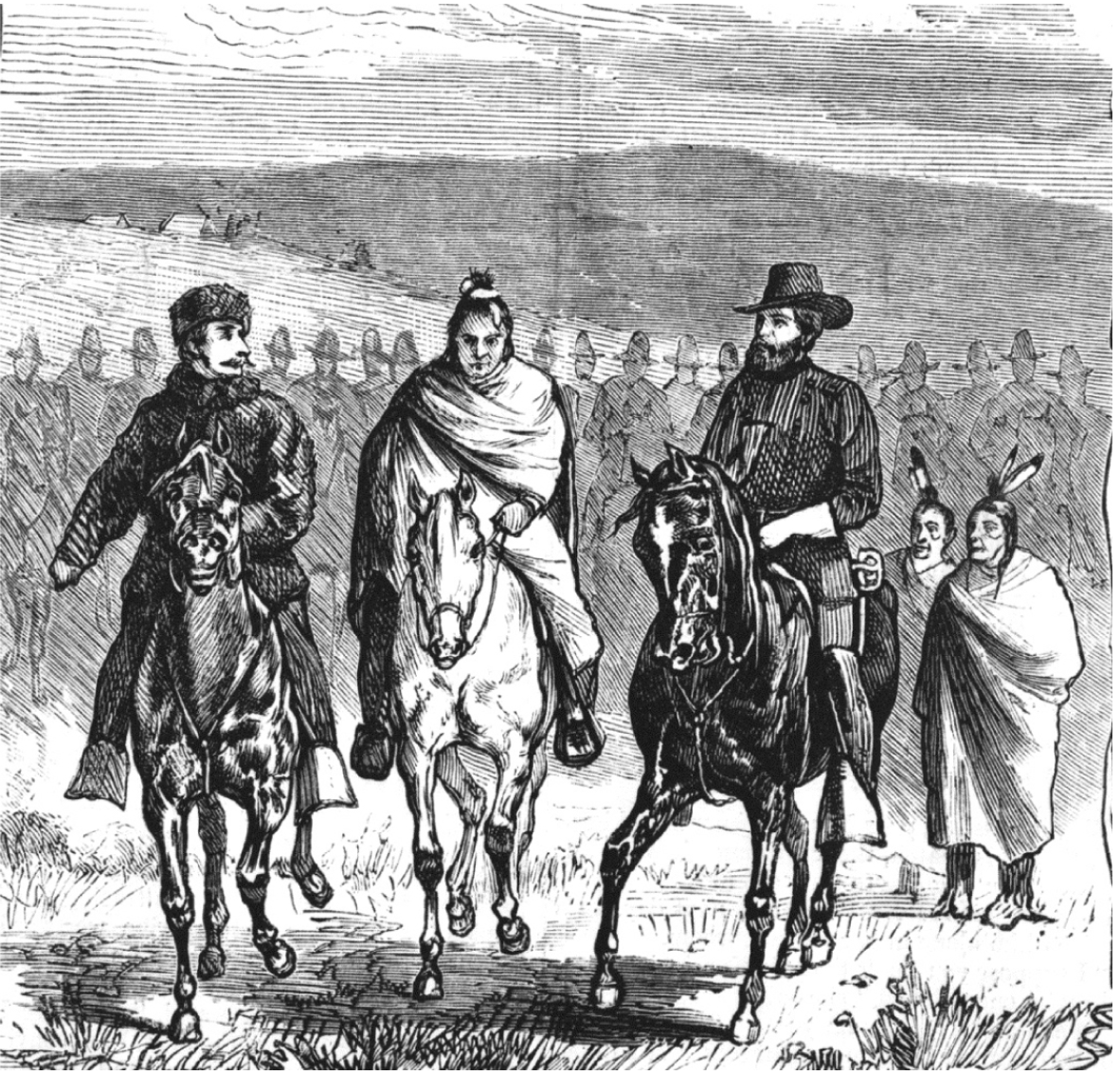

After succeeding his father as leader of the Wallowa Nez Perce in 1871, Joseph negotiated with the federal government to allow his band to stay in the Wallowa Valley. He made impassioned speeches to commissioners about his people’s link to their homeland, and his wish for Native Americans to receive equal rights. Even through an interpreter, Joseph impressed anyone who listened to him with his oratory skills and appeals to American patriotism. But as much as commissioners personally liked Joseph for his goodwill and respect for the United States, he did not sway the government from their decision to resettle his band.3 In 1877, Army General Oliver Otis Howard threatened war if Joseph did not move his band to an Idaho reservation within 30 days. Joseph reluctantly agreed, but Nez Perce warriors attacked white settlers before they arrived in Idaho Territory. Fearing retaliation by the Army, Joseph gathered around 800 Nez Perce men, women and children, and fled east. General Howard pursued Joseph with 2,000 soldiers. The Nez Perce War had begun.4

The pursuit lasted four months and covered over a thousand miles of terrain across Oregon, Washington, Idaho and Montana. In battle after battle, the Nez Perce always managed to stay one step ahead of Howard’s army. Joseph’s final objective was to cross the Canadian border and take refuge with the Lakota leader Sitting Bull, still free after his victory at the Battle at the Little Bighorn the previous year. But just 40 miles from the border in northern Montana, Howard’s army finally caught up with them, and cornered Joseph. After a journey of 1,170 miles and the loss of 200 Nez Perce lives, Joseph could go no further.5

“Hear me, my chiefs: I am tired. My heart is sick and sad. From where the sun now stands I will fight no more forever.”6

Chief Joseph surrendered on October 5, 1877, and negotiated with General Howard for the safe return of the surviving Nez Perce to the Idaho reservation. It wasn’t the Wallowa Valley, but at least the reservation was on lands formerly claimed by the Nez Perce tribe. But despite surviving the horrors of war, what came next may have been even harder.7

Joseph and the 450 Nez Perce who surrendered did not make it back to Idaho, despite their successful negotiations with General Howard. Instead, they were sent to Fort Leavenworth in Kansas to be held as prisoners of war. Eight months later, they were moved onto an Oklahoma reservation in Indian Territory. Over the duration of their exile, steaming hot summers invited diseases like malaria and cholera. Merciless winters brought pneumonia and tuberculosis. Dozens died, including virtually all of the infants born during this time, Joseph’s daughter among them.

On January 14, 1879, Chief Joseph found himself in what should have been the heart of enemy territory. Commanding General of the Army William Tecumseh Sherman wandered around the East Room of the White House, mingling with ambassadors, congressmen, journalists and socialites at the New Year’s first reception. Sherman wasn’t Joseph’s enemy any longer. He was just a fellow guest at a party. But the war’s end didn’t erase the history of bad blood that flowed between them. You see, it was Sherman who overruled Howard’s negotiation and sent Joseph and the Nez Perce into exile. Sherman wanted to make an example out of the Nez Perce to intimidate other tribes.

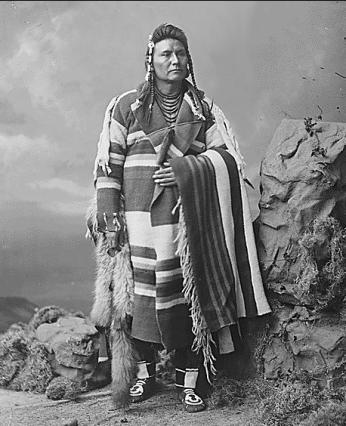

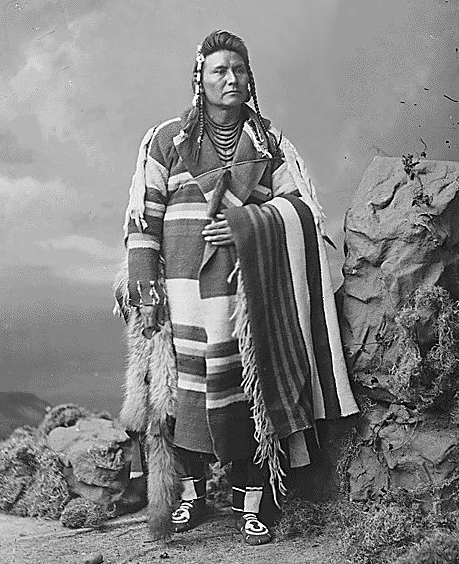

Joseph had come to D.C. to plead with President Hayes and anyone in the capital who would listen for his people’s right to return to their ancestral lands in the Wallowa Valley. Joseph was still making the same case as if months of war and years of failed negotiations had done nothing to diminish his resolve. He became a sensation in Washington after his surrender statement was echoed across newspapers and magazines. Washington elites saw Joseph not as a vanquished enemy but as a noble leader, peacemaker and humanitarian, brimming with intelligence, eloquence and empathy. Dressed in a striped blanket and with elaborate beadwork, necklaces and shell earrings, he certainly stood out among the other guests, who clustered around him.

Joseph, who barely spoke English, was accompanied by an interpreter and Yellow Bull, a fellow warrior and leader from the war. Sherman ushered his daughters through the East Room to meet the men who he described as “by far the most important guests present”.8 He held Joseph’s hand and greeted him warmly, introducing his daughters and their friends. If Joseph carried any animosity towards the men and the nation who ruthlessly subjugated him, he didn’t show it. He bowed to First Lady Lucy Hayes, a “model of courtly grace”9 as someone wrote. Secretary of the Interior Carl Schurz, who approved the plan to remove Joseph’s band from the Wallowa Valley, introduced his daughter Agathe, who invited Joseph and Yellow Bull to meet them again the next day.

The next evening, Joseph got down to business. He attended a meeting at the Department of the Interior with the Board of Indian Commissioners, the commissioner of Indian Affairs, and Alfred Meacham, who oversaw Indian affairs in Oregon when Joseph began negotiating his claim to the Wallowa Valley. Meacham had arranged Joseph’s journey to Washington. Joseph spoke only briefly, reminiscing on his years of trying to change government policy towards his people. “I have met many of the representatives of the government. I once talked with [Meacham], and tried to impress upon him the necessity of keeping my country. I was small then; I was inexperienced, but I tried to express as well as I could what I wanted. I could not see then as far as I can today, but I still had pretty nearly the same ideas. I am a wiser man today than I was then, but I think I have the same right to my country that I had then.”10

Joseph left the meeting with the commissioner of Indian affairs recognizing his claim to the Wallowa Valley, but nothing concrete changed. A couple days later, Joseph accompanied Alfred Meacham to Lincoln Hall, an auditorium north of the National Mall, for an evening pow-wow to raise funds for Meacham’s magazine The Council Fire.11 Eight hundred people paid 25 cents a ticket to see Joseph and members of visiting tribes, among a night of lectures, minstrel shows and violin concerts. Native American speakers recounted their stories of cruelty and injustice at the hands of settlers, prospectors and the U.S. government. Joseph spoke for over an hour, captivating the audience with a story of displacement, war, and broken promises, but also of friendship and honor. Joseph may have once been an enemy of the United States, but he never let listeners forget the friendship he believed the Nez Perce still had with the country. He told the story of his father’s dying wish, to protect the grave and the land where Joseph the Elder was buried.12

The audience loved him. They gasped and laughed at his stories of daring escapades during the war. They cried when he remembered the suffering his people endured on the malaria-infested reservation after his terms of surrender were broken. Joseph was a gifted storyteller. He gestured and mimed, “which for grace and appropriateness would have done credit to a Frenchman,”13 one reporter wrote. But it was Joseph’s final words that remained the most powerful. “If the white man wants to live in peace with the Indian, he can live in peace. There need be no trouble. Treat all men alike. Give them all the same law. Give them all an even chance to live and grow.”14

One key to how Joseph moved his audience was that he appeared to genuinely admire the United States for its values of liberty and equality. His speeches appealed to Americans to commit to these values and apply equal citizenship to Native Americans. “Let me be a free man, free to travel, free to stop, free to work, free to trade where I choose, free to choose my own teachers, free to follow the religion of my fathers, free to think and talk and act for myself - and I will obey every law, or submit to the penalty. This is my story and here I am,”15 he finished.

Articles, poems and tributes about Joseph ran in newspapers and magazines for months after his speech at Lincoln Hall. Not everyone thought Joseph’s celebrity could amount to real change for the Nez Perce. “Theoretically it was a good, a fine and a noble thing when an oppressed and captive savage could speak out in this free and open way,” one journalist wrote, using language that was sadly common at the time. “But where is the good that will ever come of it? His whole tribe may die off from the strange and unhealthy climate in which they have been assigned a camping place, and there will be no help for them.”16

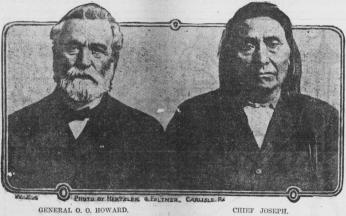

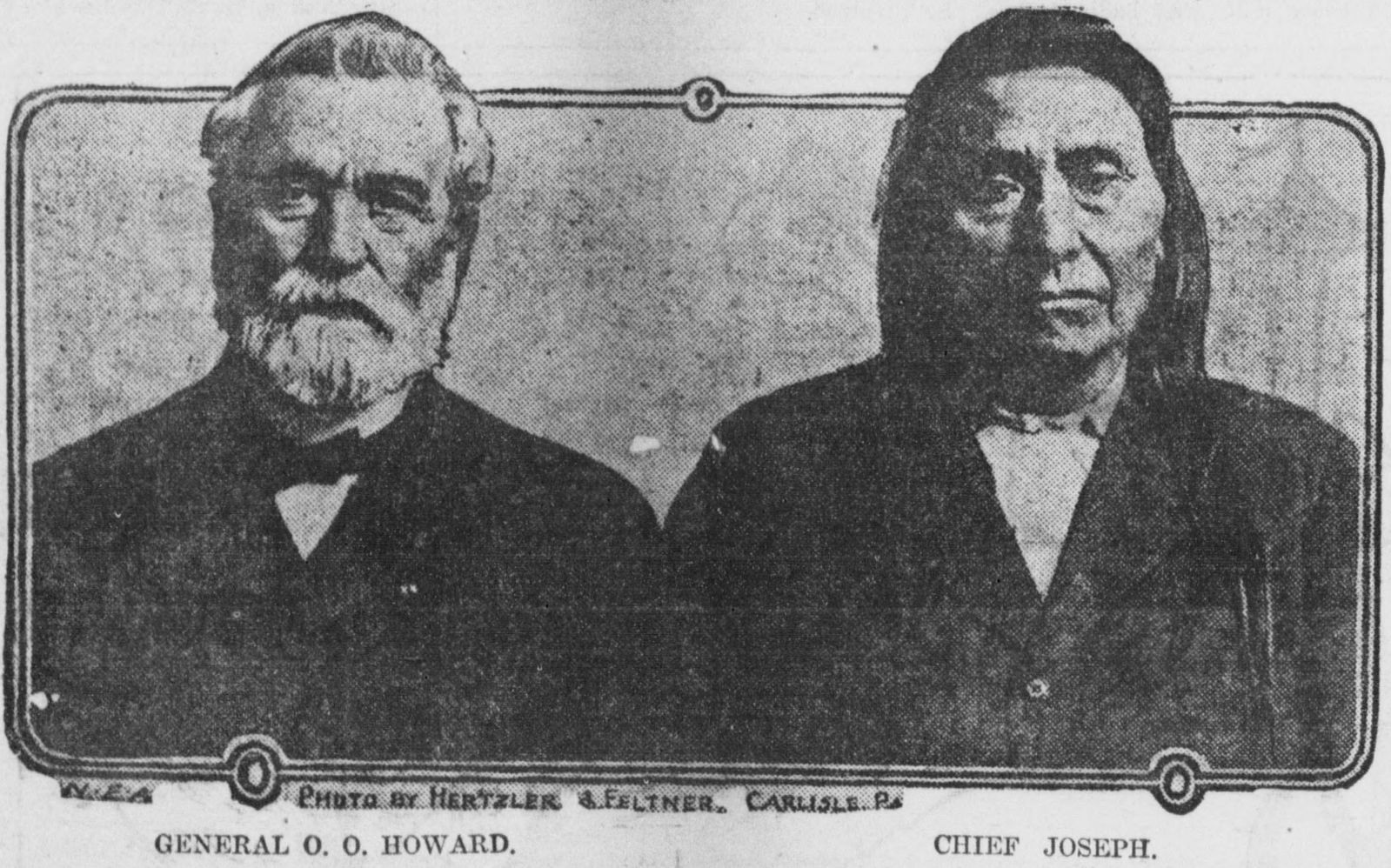

If Joseph was a hero in Washington’s eyes, then the villain was unmistakably the general who pursued him, Oliver Otis Howard. Despite his heroism in the Civil War and his championship of civil rights during Reconstruction, Howard never earned the respect and adoration he so desperately craved, at least not within his lifetime. Howard University is named after him. His handling of the war spurred criticism across the country, and recognition of his mistreatment of the Wallowa Nez Perce only became more widespread after his victory.17, 18, 19, 20 However, the two former enemies always respected each other. Joseph and Howard had an emotional reunion months before Joseph’s death.21

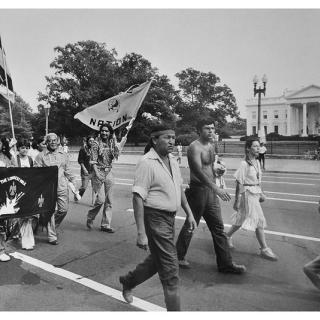

Joseph settled onto the Colville Indian Reservation in Nespelem, Washington in 1885, where he would reside until his death in 1904, at the age of 64.22 He was back in the Pacific Northwest, but far away from the Wallowa Valley and most of the scattered Nez Perce. He spent his final years speaking out against the injustices the American government inflicted upon his people, and to reiterate his hope for the American people to one day apply freedom and equality to Native Americans. Joseph returned to Washington in 1897 to make his case, this time with President William McKinley, and then again in 1903 with President Theodore Roosevelt.23

Chief Joseph may not have dramatically altered the fate of his people by visiting D.C., but he captured the heart of a nation that had dehumanized and oppressed Native Americans for centuries. His spirit of sovereignty and equal rights lives on through Native Americans and his band of Nez Perce, who still reside on the Colville Indian Reservation in Washington. The route of his retreat during the Nez Perce War was designated a national historic trail in 1986.24 Joseph’s visit may only be a footnote in the annals of D.C. history, but his mark on the nation is indelible.

Footnotes

- 1

Swagerty, William R. “Chief Joseph and the Nez Perce Indians.” Chief Wakashie Foundation, June 8, 2005.

- 2

Hoggatt, Stan. “Political Elements of Nez Perce History during Mid-1800s & War of 1877.” Historical. Western Treasures, 1997.

- 3 Nerburn, Kent. Chief Joseph & the Flight of the Nez Perce: The Untold Story of an American Tragedy. HarperOne, 2006.

- 4

Johnson, Johnny. “War of 1877: Centennial of Sorrow.” Lewiston Morning Tribune, July 24, 1977.

- 5 The West. Series, Documentary. PBS / WETA, 1996.

- 6

Weaver, Jace. “I Will Fight No More Forever.” Teaching American History (blog), n.d.

- 7 Haines, Francis. “Chief Joseph and the Nez Perce Warriors.” The Pacific Northwest Quarterly 45, no. 1 (January 1954): 7.

- 8 Sharfstein, Daniel J. Thunder in the Mountains: Chief Joseph, Oliver Otis Howard, and the Nez Perce War. W. W. Norton & Company, 2017.

- 9 Sharfstein, Daniel J. Thunder in the Mountains: Chief Joseph, Oliver Otis Howard, and the Nez Perce War. W. W. Norton & Company, 2017.

- 10 Sharfstein, Daniel J. Thunder in the Mountains: Chief Joseph, Oliver Otis Howard, and the Nez Perce War. W. W. Norton & Company, 2017.

- 11

Streets of Washington: Stories and images of historic Washington, D.C. “Briefly Noted: Lincoln Hall.” Blog, July 11, 2012.

- 12

Joseph, Young, and William H. Hare. “An Indian’s Views of Indian Affairs.” The North American Review, April 1879.

- 13 Sharfstein, Daniel J. Thunder in the Mountains: Chief Joseph, Oliver Otis Howard, and the Nez Perce War. W. W. Norton & Company, 2017.

- 14 Sharfstein, Daniel J. Thunder in the Mountains: Chief Joseph, Oliver Otis Howard, and the Nez Perce War. W. W. Norton & Company, 2017.

- 15 Sharfstein, Daniel J. Thunder in the Mountains: Chief Joseph, Oliver Otis Howard, and the Nez Perce War. W. W. Norton & Company, 2017.

- 16 Sharfstein, Daniel J. Thunder in the Mountains: Chief Joseph, Oliver Otis Howard, and the Nez Perce War. W. W. Norton & Company, 2017.

- 17

Smith, Samuel J. “Educational Reformer & Christian Soldier: General Oliver Otis Howard.” Wayback Machine, March 2, 2019.

- 18

Schmidt, Michelle. “It’s Complicated: There’s More to General Howard than His Pursuit of Chief Joseph.” Inland 360, July 25, 2017.

- 19

Mackowski, Chris. “Chief Joseph: If Not for Howard, ‘There Would Have Been No War.’” Emerging Civil War, October 5, 2018.

- 20

Sharfstein, Daniel "The Namesake of Howard University Spent Years Kicking Native Americans Off of Their Land" Smithsonian Magazine May 23, 2017.

- 21

The Tacoma Times. “The Touching Reunion of Old Foes: An Object Lesson to Many Hundreds.” March 5, 1904. Library of Congress.

- 22

The New York Times. “CHIEF JOSEPH DEAD.” September 24, 1904.

- 23 Sharfstein, Daniel J. Thunder in the Mountains: Chief Joseph, Oliver Otis Howard, and the Nez Perce War. W. W. Norton & Company, 2017.

- 24

Walter, Jess. “Congress Asked to Save Chief Joseph’s Grave.” The Spokesman Review, July 4, 1991. Google News.

![Sketch of the mythical fuan by Pearson Scott Foresman. [Source: Wikipedia]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2023-10/Goatman_Wikipedia_Faun_2_%28PSF%29.png?h=64a074ff&itok=C9Qh-PE1)