"Belair at Bowie": the Suburban Dream

In the years following World War II, Americans realized that they were ready for peace and quiet. After the stress of the Great Depression and the horrors of an international war, it seemed time to settle down. Young people, especially, craved normalcy and comfort. They got married, moved out of their cramped apartments, and created idyllic domestic lives with their growing families. But there was a problem: there weren’t actually enough houses for them.

Enter William Levitt, a property developer from New York City. Having served in the war himself, Levitt recognized the growing demand for affordable, reasonably sized family homes away from busy city life. In 1947, he purchased land on Long Island and built the perfect neighborhood: new homes in a variety of styles, tailor-made for veterans and their new families. Levitt tried to cut construction costs wherever possible, ensuring that his homes were affordable without loans: he made deals with lumber suppliers, established his own factories, and pioneered assembly-line construction that required less labor time. “Obviously you can’t move houses down a conveyor,” reported The Washington Post, trying to explain the Levitt method to its readers. “But you can move specialized workers along a line of houses. And you can arrange delivery of materials ... just like the flow of automobile parts to an assembly line.”[1] As an added perk, he even included the latest appliances — electric stoves! refrigerators! — in the cost of every home. Levitt’s scheme, however unconventional it seemed to the public, ended up being a success — his community filled rapidly. By late 1948, Levitt’s company had built 8,000 new houses — the cheapest went for around $8,000.[2] The success inspired more growth; throughout the 1950s, Levitt communities appeared in New York, New Jersey, and Pennsylvania. Today, we know these tranquil, homogenous developments as “suburbia.” Levitt, capitalizing on his new fame, named them all “Levittowns.”

In the late 1950s, Levitt was ready to expand again — this time, to a different metropolitan area. Although he had once tried and failed to establish an earlier community in Norfolk, Virginia, Levitt remained certain that he could find success in the Washington, D.C. region. He suspected government employees — many of them former servicemen — were a perfect market for his homes. Now the hunt began for a perfect location: somewhere quiet, but still easily accessible.

In 1957, Levitt chose a small town in Prince George’s County, Maryland as the site of the new Levittown. Located off of two convenient highways, Bowie was only home to about 600 people — the closest middle-of-nowhere to the District.[3] Hoping to bring some novelty and character to the new development, the Levitt company purchased the enormous, historic Belair Estate: a 2,280-acre colonial plantation and horse farm that was once the home of Maryland governors.[4] To honor the site’s history, Levitt decided to break with his tradition and keep the local name for his development. Construction of “Belair at Bowie,” a community of new homes with a colonial mansion at its center, began in 1960.

“America’s biggest builder of single-family homes has moved into the Washington suburban area,” the Post reported in July 1960.[5] Once again, Levitt’s company built quickly and efficiently, using the assembly-line method that attracted so much national attention. The local newspapers were certainly interested in the scheme, wondering how the new Bowie houses would resemble but differ from their predecessors in New York, New Jersey, and Pennsylvania. It was rumored that Levitt planned to include all of the latest modern conveniences, including central air conditioning — a must for D.C. summers. The Post was baffled when they discovered that the new homes were “basementless,” having been built on concrete slabs.[6] But ultimately, the affordable cost of the properties was the largest draw. Before construction had even finished, Levitt promised Washingtonians that his “selling prices would be total prices with no closing costs, no legal fees, [and] no added financing fees.”[7] It was the perfect deal for young families and working professionals.

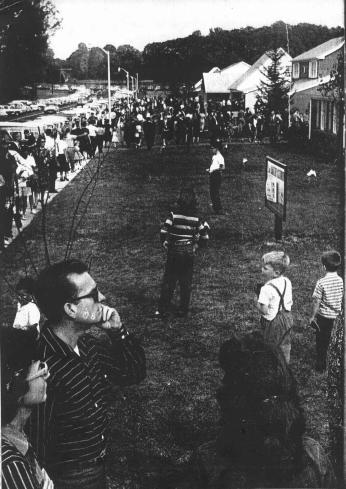

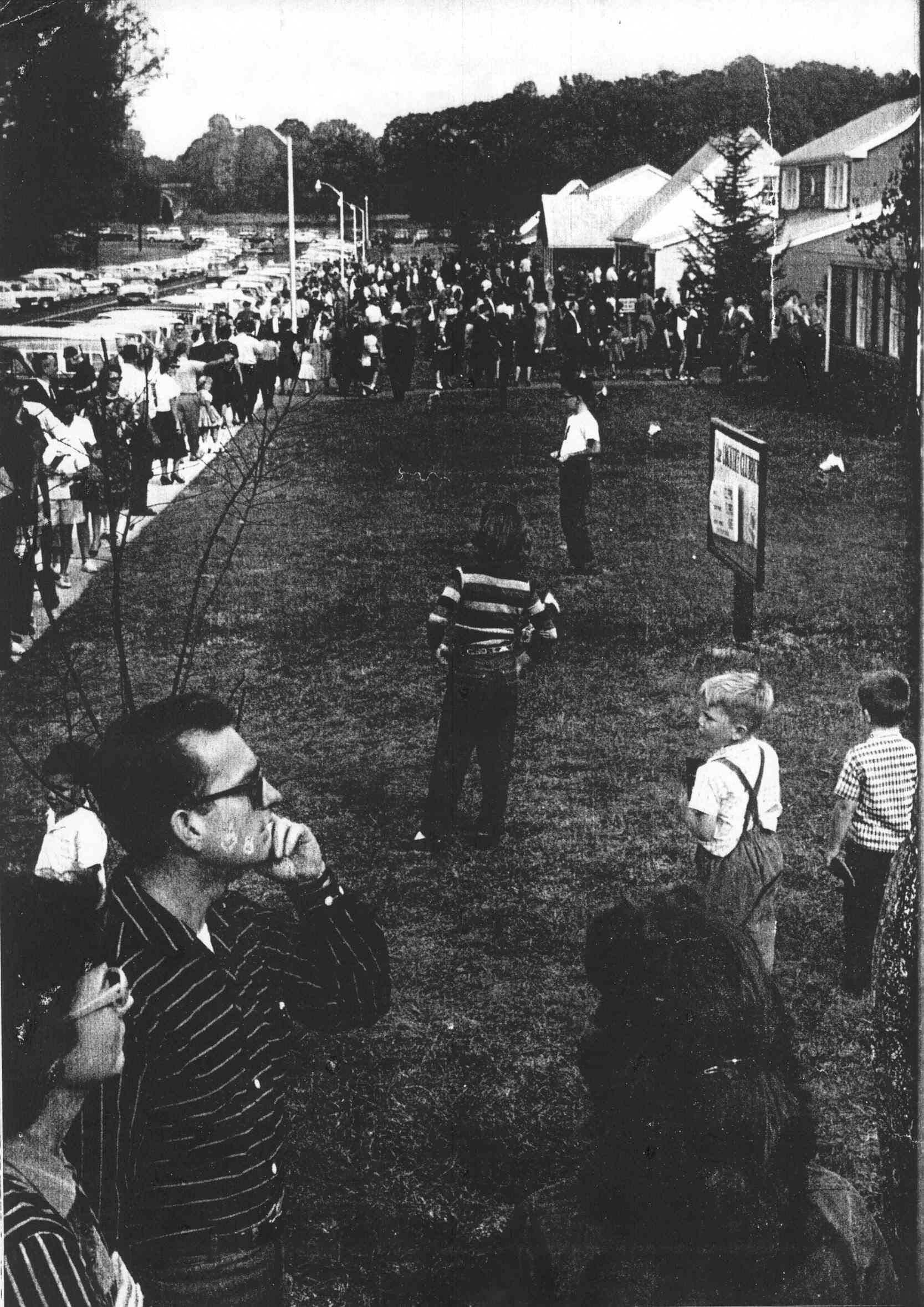

A street of model homes opened to prospective buyers on October 8, 1960. It was a dreary, drizzly day, but the weather didn’t stop 20,000 visitors from attending Levitt’s grand opening.[8] Traffic was backed up for 1 1/2 miles as families tried to park near the site, while lines outside of the Levitt offices extended all the way down the street.[9] Thanks to all the local hype, Levitt was ready to operate on a first-come, first-serve basis. Within a week, his company sold 243 of their available lots — over $4 million worth of property.[10]

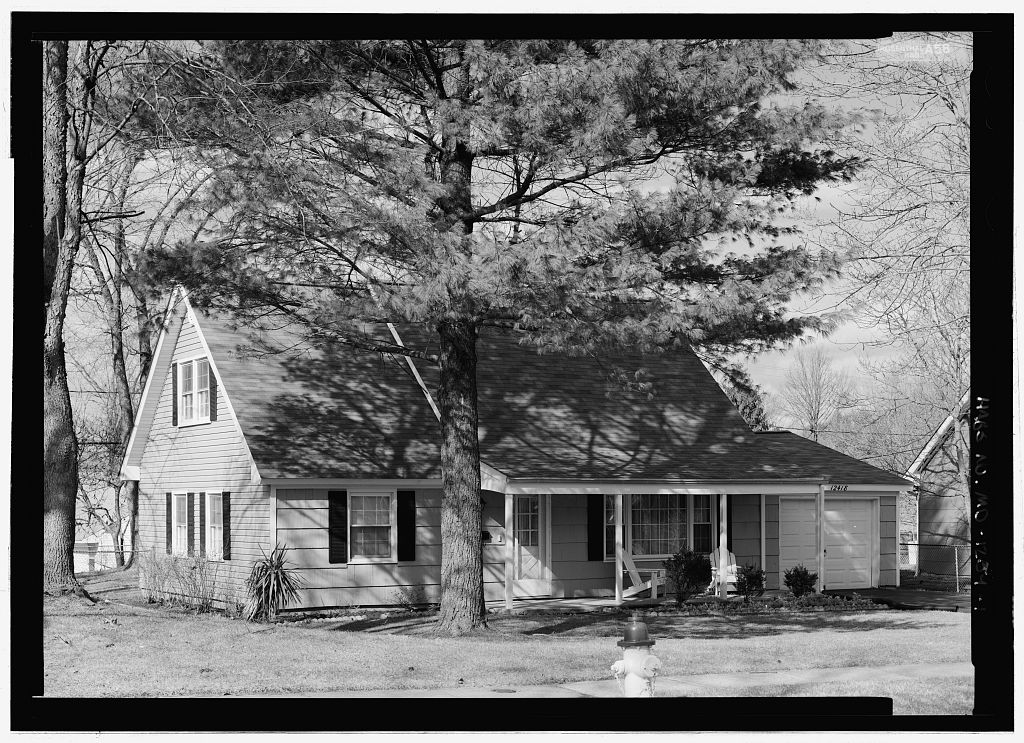

Clients who attended the “open house days” could view model homes in five different styles: the “Country Clubber,” three and four-bedroom “Colonials,” the “Rancher,” and the “Cape Cod.” As attending real estate agents explained, these homes could be customized and personalized by their buyers, based on budget and personal taste. The colors of houses — as well as kitchen and bathroom appliances — were decided by the builders ahead of time, so families could choose the exact model and color combination they liked best. Most lots were similarly sized at 8,400 square feet, to ensure fairness of price — but some, including corner lots and a few “suitable for doctors or dentists” and their practices, were priced higher.[11] The streets, street lights, sewers, and water pipes were pre-installed and municipally operated.[12] And, as rumored, each Belair home included “all the extras you’ll need for comfortable living”: appliances, central air conditioning, electrical fixtures, painting, landscaping, garages, driveways, built-in TV-FM antenna systems, and more.[13]

There was another draw: Levitt wasn’t just building a housing development, he was trying to create a new community. The advertising brochures, given to all prospective buyers, outline his plans for a town surrounding the new houses:

“Land is set aside and donated by Levitt for houses of worship of practically every major faith…the shopping center in Belair will have a variety of excellent stores ... land has been set aside for the use of the Board of Education for new schools ... [and] owner-residents of Belair will receive membership priority in the Bath and Tennis Club soon to be erected by Levitt and Sons, Inc.”[14]

It also explains the reasoning behind Levitt’s various house styles and colors: by mixing the types of homes on each street, as well as their colors, the builders created “greater variety and a pleasing neighborhood scene.”[15] These weren’t the now-stereotypical “cookie-cutter” homes. In fact, Levitt even decided to create curved streets and cul-de-sacs to make the development seem less planned.

For anyone who has ever bought a home in a new development, these details may seem standard practice — but for Washingtonians at the time, the process was revolutionarily easy and convenient. Plus, the prices couldn’t be beat. Just as Levitt promised, each spacious house — with land and amenities included — was affordable for the average middle-class families. The cheapest Belair model, the four-bedroom Cape Cod, started at $15, 990 — at signing, all a buyer needed was a “good-faith” deposit of $100.[16]

The first six Belair families moved into their new homes just over a year later, on October 17, 1961. Thereafter, the community grew by at least seventy-five occupancies each week — the Post called it a “take-possession hegira.”[17] After a year of sales, over 1,500 families purchased and reserved lots; most interested parties had their names placed on waiting lists, hoping for future streets to be added.[18] Spurred on by this massive success, Levitt’s company planned additional neighborhoods in their emerging village — to add some character and charm and make it easier to navigate, each “section” would be organized by letter. The original Belair neighborhood, Somerset, has streets that all begin with “S.” It was quickly followed by Buckingham, Kenilworth, Foxhill, and Tulip Grove — or, to a Bowie native, the “B,” “K,” “F,” and “T” sections, respectively. Houses went up so quickly that, on one visit to a construction site, a Post reporter asked a builder how long it actually takes to make one. “’How soon do you want it?’ he cracks back. ‘We could build ‘em overnight. Don’t laugh ... it’s been done.’”[19]

That same reporter wrote a vivid description of Belair in early 1962, two years after construction first began. Her account doesn’t quite describe the idyllic paradise that Levitt clearly wanted, but does show that rapid expansion was just part of the experience:

“At eye level, the same vista is a jumble of brightly colored shutters, rooftops, mud, trucks and workmen. The air smells of fresh paint and newly turned earth. Children are in galoshes against the mire surrounding almost every house. Tradesmen track a muddy path into virgin sales territory. Yards can’t be sodded yet and fluctuating temperatures make the oozing earth look like brown meringue.”[20]

Reasonable price tags aside, there were plenty of reasons for moving to the new Levittown — despite all the mud and construction noise. New residents felt that they were getting that new start in life, exactly what they craved after the uncertainties of the previous decades. It was the new American dream. “The peace and quiet are heavenly,” a resident reported, adding that “the idea of a brand new community starting all at once ... has a pioneer spirit.”[21]

Levitt continued to be active in the area until the late 1970s, adding numerous sections, churches, schools, and shopping malls to his ever-expanding vision — in fact, thanks to Levitt, Bowie is now the fifth most populous city in Maryland. The majority of residents still live in Levitt homes and, in some cases, are their original and sole owners. Growing up in Bowie, it was never unusual to visit a new friend’s house and discover that, with a few exceptions, it looked exactly like your own. And the alliterative sections became such a tradition that even more recent developers have followed the trend, capitalizing on previously unused letters of the alphabet.

But the prosperity of Bowie, even today, hides an uncomfortable truth. William Levitt’s vision of the perfect neighborhood included attractive homes, affordable prices, comfort, and community — but only one type of neighbor. From the moment Levitt arrived in Washington, local activists — and even the government —b ecame aware of the developer’s racist policy: none of the homes in Belair could be sold to people of color.

Footnotes

- ^ T.E. Applegate, “Housing ‘Giant’ Building 150 Homes Per Week,” The Washington Post, October 10, 1948.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ “Maryland Town Officials Rap Curb on Annexation,” The Washington Post, March 11, 1959.

- ^ “Belair Mansion,” The City of Bowie, Maryland, https://www.cityofbowie.org/288/Belair-Mansion

- ^ “Mr. Levitt Comes to Town,” The Washington Post, July 9, 1960.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ “Levitt’s Biggest Opening,” The Washington Post, October 15, 1960.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Belair at Bowie Maryland (Levitt and Sons, 1961).

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ John B. Willmann, “Levitt Sets M-Day For Belair Homes,” The Washington Post, September 30, 1961.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Victoria Velsey, “Levitt Moves In and Pastureland Becomes a Town,” The Washington Post, January 1962.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Ibid.

![Sketch of the mythical fuan by Pearson Scott Foresman. [Source: Wikipedia]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2023-10/Goatman_Wikipedia_Faun_2_%28PSF%29.png?h=64a074ff&itok=C9Qh-PE1)