What's in a Name? The State Avenues

There are fifty-one streets in D.C. named for every state and Puerto Rico. But, admittedly, not all state avenues are created equal. Some are long, vital roadways through our city. Others are historic and prominent—the location of our country’s most important events. And some are…well, a bit hard to find. Admit it: you probably couldn’t point to all of them on a city map. So why are some state avenues more prominent than others? Is there any method to the naming madness?

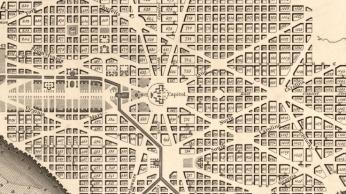

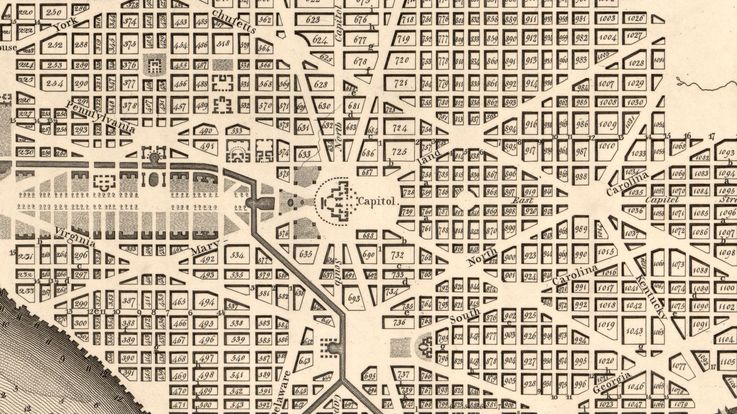

In his designs for the new capital city, Pierre L’Enfant planned a logical, well-organized grid system of streets. As we know, most of these streets follow numerical and alphabetical patterns—so, ideally, it’s hard to get lost when walking the D.C. blocks. But L’Enfant also planned a series of diagonal avenues—modeled after the Champs Élysées in Paris—that cut through the grid, all meeting and intersecting at the Capitol building.[1] These avenues were meant to ease traffic, encourage growth to the city’s outer regions, and connect the District with outlying towns in Maryland and Virginia.[2] Instead of numbers and letters, they would carry the names of the thirteen states.

Historians aren’t really sure how city planners chose to name these important new roads, but some certainly got better placement than others. Pennsylvania, for example, lent its name to one of the most important new avenues: the one connecting the Capitol to the Presidential Mansion, offering clear views of both seats of power. Certainly, Pennsylvania was an important colony—especially during the Revolution, when it hosted the Continental Congresses. It was also home to the country’s first national capital: Philadelphia. One theory suggests that the Avenue’s name actually honors the location of the former capital city. It might also appease Pennsylvanians after the capital’s removal to Washington—now the city’s most important processional street would carry their name.[3]

However, it’s far more likely that the name is more coincidental. The local historian Frederick Fishback, writing in 1917, explains that “the name of Pennsylvania, because it was the central one of the original thirteen states, was most appropriately given to this thoroughfare in the center of the city.”[4] In this case, “central” doesn’t mean “most important”—it refers to Pennsylvania’s location in the center of the colonial map. As it turns out, L’Enfant planned to organize the state avenues just as logically as the other streets. The mid-Atlantic states—Pennsylvania, New Jersey, Delaware, and Maryland—could find their respective avenues in the center of the city. To their north ran the avenues named for the New England states, like Massachusetts and Connecticut. To their south were—you guessed it—the avenues named for the southern states, like Virginia and Georgia.

But this logical system didn’t last. As the city and country expanded, new streets in Washington carried the names of the new states—though in no particular pattern. States were being added so sporadically that city planners couldn’t really stick to the geographically-organized plan. And within the city boundaries, there really wasn’t enough room for every state to have its broad, diagonal avenue. In 1890, the road that established the District’s northernmost border—the aptly named Boundary Road—got a name change to reflect the growing city’s needs. Although north of city center, this confusing, meandering road is now known as Florida Avenue.

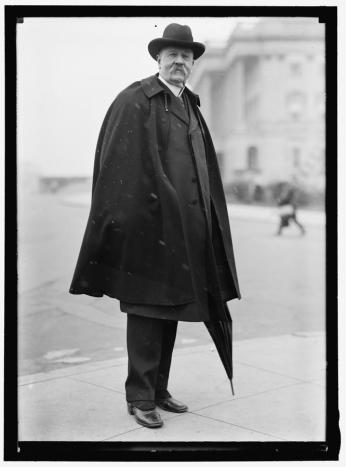

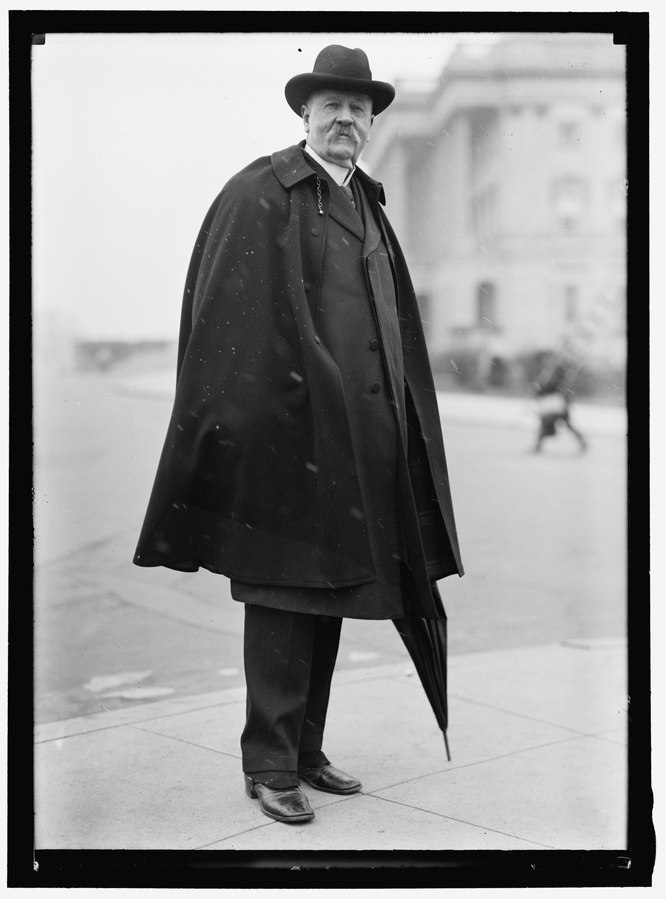

Of course, some states—perhaps jealous of Pennsylvania’s prime avenue—became offended by the small size or perceived unimportance of their respective avenues. In 1908, “the logical system of avenue nomenclature was unfortunately changed” when Augustus Octavius Bacon, a senator from Georgia, lobbied to change the location of his state’s avenue to a more well-known, trafficked route to towns in Maryland.[5] His proposal turned out to be unpopular—residents of the District were “unanimously opposed” to any name change, especially since “the name Georgia Avenue had been given to that thoroughfare more than a hundred years ago by the founders of this city.”[6] Bacon eventually won his suit, however, and the former Brightwood Avenue in Northwest became Georgia Avenue. The former Georgia Avenue is now Potomac Avenue.

All in all, though, there doesn’t seem to be a precise naming process for Washington’s state avenues. Though organized at first, the avenues are now spread all over the city, regardless of their position on the national map. And don’t worry: the size of your home state’s avenue doesn’t really have anything to do with that state’s importance to the country, either. Some states just got lucky—or cared way too much.

Footnotes

- ^ Scott W. Berg, Grand Avenues: The Story of Pierre Charles L’Enfant, the French Visionary Who Designed Washington, D.C. (New York: Vintage Books, 2008), 78.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ “Pennsylvania Avenue National Historic Site and Old Post Office Building,” Washington, D.C. National Register of Historic Places, https://www.nps.gov/nr/travel/wash/dc41.htm

- ^ Frederick L. Fishback, “Washington City, Its Founding and Development,” Record of the Columbia Historical Society 20 (Washington, D.C., 1917), 220.

- ^ Fishback, 221.

- ^ “Citizens Object to Change,” The Washington Evening Star, May 2, 1908.

![Sketch of the mythical fuan by Pearson Scott Foresman. [Source: Wikipedia]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2023-10/Goatman_Wikipedia_Faun_2_%28PSF%29.png?h=64a074ff&itok=C9Qh-PE1)