The Congressional Cemetery: Forgotten and Found

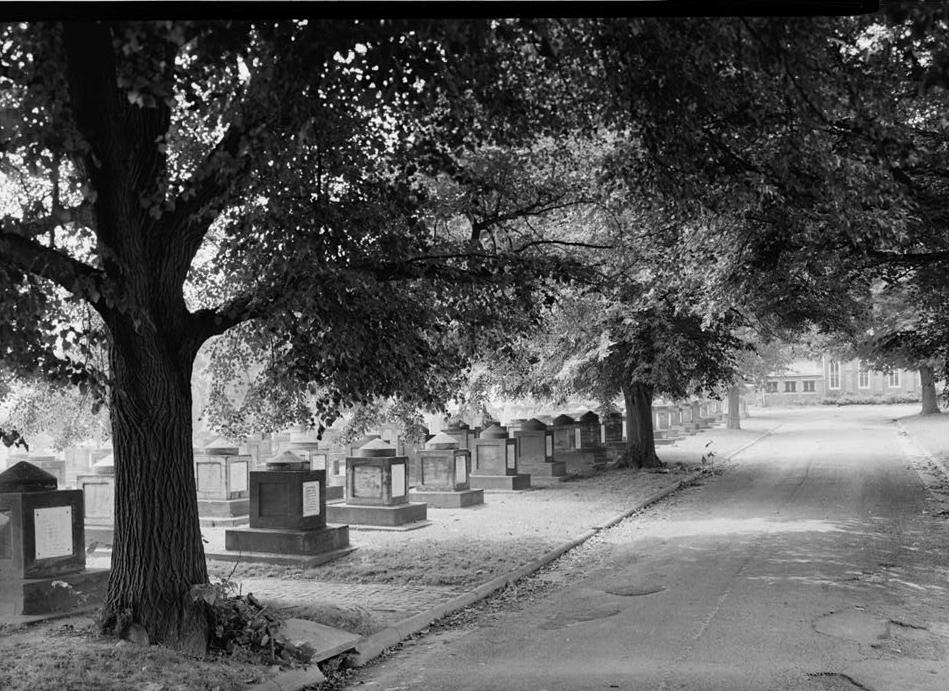

In the 1970s, the Congressional Cemetery was in trouble. After years of neglect, it looked abandoned: broken headstones littered the ground, family vaults caved in, and the grass was waist high. The cemetery’s dark, sprawling grounds made it a perfect haunt for vandals and criminals. In the nineteenth century, this was one of the most well-known and fashionable burial grounds in Washington—where politicians, heroes, celebrities, and local personalities were laid to rest. But it seemed as though the Congressional Cemetery’s rich history had been forgotten.

Forgotten, maybe, but certainly not lost. Fifty years later, the cemetery has undergone a stunning transformation. As well as being an active burial ground—there are still up to 100 burials every year—it serves as a community garden, urban wildlife sanctuary, place of remembrance, and historic site. Volunteers, many from the local Capitol Hill neighborhoods, work tirelessly to keep up the grounds and reverse the damage of decades past. The site’s new managerial organization, known as the Association for the Preservation of Historic Congressional Cemetery (APHCC), promotes the site’s unique history and ensures its future preservation. “I have the mindset that I’m a temporary steward of these historic artifacts,” the APHCC President, Paul Williams, told me in an interview.[1] “I want to make sure that they’re all still here 100 years from now…so that when tourists are coming then, they’ll enjoy it just as much as I do.”

Because, as it turns out, the Congressional Cemetery has always been a people’s effort. Despite its official-sounding name, and despite its importance to national history, its story is much more local.

In the first place, the cemetery owes it creation to a group of concerned citizens. When Pierre L’Enfant first planned and designed the national capital, he didn’t seem to be thinking about the needs of future inhabitants. Early maps of the District include government buildings, a presidential mansion, and grand avenues—but more practical spaces, like cemeteries, are curiously absent. The parishioners of Christ Church, a small community on the eastern side of the city, decided to take matters into their own hands. In April 1807, they chose 4.5 acres of land—a square between E and G Streets and 18th and 19th Streets SE—to serve as their local burial ground. Officially, this new cemetery was known as the Washington Parish Burial Ground—a nod to the people who created it.

But because of its proximity to Capitol Hill, it didn’t take long for the cemetery to become associated with Congress. The first person buried there—interred on April 11, 1807, just days after opening—was William Swinton, a stonecutter working on the Capitol building.[2] Three months later, Senator Uriah Tracy of Connecticut died in office and became the first member of Congress buried in the cemetery. The Washington Parish, capitalizing on an important connection, set aside 100 gravesites for any other unfortunate Congressmen.[3] It started a tradition that lasted until the mid-1830s: the majority of Congressmen who died in Washington were laid to rest within the parish burial ground. The architect of the Capitol, Benjamin Latrobe, even designed a series of identical cenotaphs to memorialize those Congressmen who chose to be buried elsewhere. Eventually, the cemetery’s original name was all but forgotten: most Washingtonians (and visitors) just referred to it as the “Congressional Cemetery.”

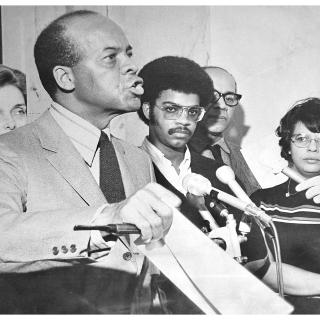

As the cemetery’s Congressional connections made it more famous and popular, the grounds expanded to accommodate the demand for burial sites. Eventually, it encompassed thirty-five acres—expertly landscaped and featuring 45,000 impressive memorials.[4] While walking through Congressional Cemetery, you’re sure to stumble across someone you’ve heard of. Many of the people featured on the Boundary Stones blog—Dolley Madison (briefly), Anne Royall, Mathew Brady, John Philip Sousa, and J. Edgar Hoover, to name a few—were buried there. It hosted the elaborate funerals of Presidents Zachary Taylor and John Quincy Adams. In the twenty-first century, a more local politician joined the ranks: Mayor Marion Barry. But not every person buried there carries national renown—some have humbler, but no less exciting, stories. Williams’s favorite lesser-known burial is that of Charles Siegert, a nineteen-year-old who worked for a traveling circus and was killed by tigers in 1899. Interestingly enough, Siegert’s headstone is actually relatively new—after the APHCC began to tell stories of the “tiger boy,” a group of circus enthusiasts raised $5,000 to memorialize him, 116 years after he died.

Beginning in the twentieth century, Congress rarely used the cemetery for official burials. Members of Congress who died in office could now be sent home for burial, since embalming and transportation had become so efficient. Some locals still chose to bury their loved ones in the once-fashionable cemetery, but without Congressional support, the site suffered from lack of funds. Christ Church also abandoned the cemetery, so staff was limited. Without caretakers to manage the grounds, all of the once-beautiful landscaping became overgrown. For anyone to be buried in the cemetery, paths were mowed to specific funeral and burial sites—it was impractical to do anything else. By 1997, Congressional Cemetery was on the National Trust for Historic Preservation’s list of most endangered historic sites.[5] Once again, it took a group of locals to give the Congressional Cemetery its next chapter.

This time, though, the heroes were a bit of an unlikely group: the Congressional Cemetery’s “K9 Corps.” Knowing that the extensive grounds made it an ideal spot for dog walking, Capitol Hill residents began to take an interest in the cemetery again. Bit by bit, they mowed the overgrown grass and repaired broken headstones. They even taxed themselves, in order to pay for all the necessary work. Locals began to use the cemetery again as their local garden, playground, and meeting place. In 1976, due to the renewed interest in the cemetery, the APHCC formed to take control of day-to-day operations. They also encouraged the historical restoration of the cemetery, knowing it was an impressive local landmark that deserved more attention.

Today, APHCC still works to uncover the Congressional Cemetery’s fascinating history—literally. Though the grass is mowed, paths have been repaved, and much of the architecture has been repaired, there’s still a lot of work to be done. Of those 45,000 headstones, there are still between 5,000 and 7,000 that need attention. Staff and volunteers give tours, host events, and do research that support their ongoing restoration and preservation efforts. And Williams knows that there are still plenty of stories to be discovered within the massive site. “I would force myself and my staff to go out and get lost on purpose,” he told me. “And, inevitably, you pause and you read the information on the headstones…there’s going to be one that captures your imagination.”

During this year’s lockdown, the Congressional Cemetery had to close for the first time in its history—even for its beloved dog-walking club. But the staff hopes that, as it always has done, the cemetery will recover from any setbacks. Thanks to the local community, its history is one of resilience. And though the Congressional Cemetery is forever linked to its famous political inhabitants, it’s important to remember that—like so many other things in Washington—its history is both national and local. For the volunteers and staff who work to keep it alive, this is a people’s cemetery.

To learn more about the Congressional Cemetery, visit their website!

Footnotes

- ^ Paul Williams, interviewed by the author (July 2, 2020).

- ^ Rebecca Boggs Roberts and Sandra K. Schmidt, Images of America: Historic Congressional Cemetery (Charleston: Arcadia Publishing, 2012), 7.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ “A Brief History of Congressional Cemetery,” Congressional Cemetery, https://congressionalcemetery.org/history/

- ^ Ibid.

![Sketch of the mythical fuan by Pearson Scott Foresman. [Source: Wikipedia]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2023-10/Goatman_Wikipedia_Faun_2_%28PSF%29.png?h=64a074ff&itok=C9Qh-PE1)