When the Secret Service Was Only Interested in Money

In certain corners of the internet, you can actually buy money. You might spend $5 for a $1000 bill, or $125 for a $20 bank note. Of course, there’s a catch: the money for sale is obsolete. These bills are relics of the Free Banking Era that reigned from the 1830s to the 1860s.

In the 19th century, American currency was in flux. Before the Civil War, paper money was not standardized, meaning that every private bank issued unique notes, many of which looked nothing like the green pieces of paper we know today. The iconography was eclectic, ranging from nationally predictable images (like George Washington and the capital’s monuments) to regionally specific designs, featuring everything from bullfrogs to Santa Claus.[1]

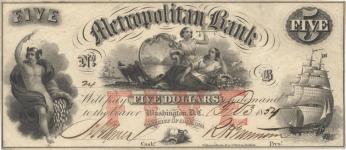

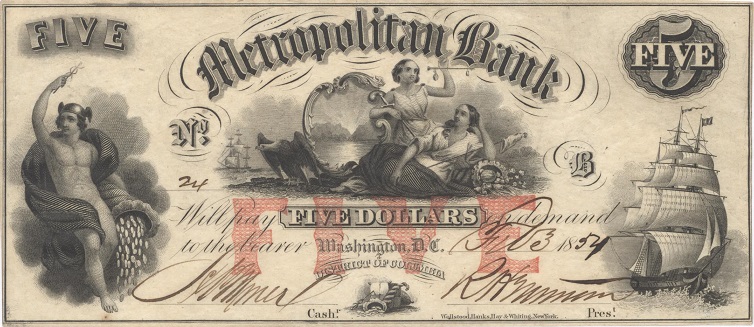

One example of Washingtonian currency is a five dollar bank note, issued by the Metropolitan Bank in 1854. On the left, it features a nude figure of the Roman god Mercury wielding an overflowing bag of coins. To the right is a large ship, and centrally we see two women, an eagle and a cornucopia. In overlain red block letters, appears the word “FIVE.” At this point in time, there were thirty banks in the D.C. area, which means that there were dozens of different local currencies in circulation, in addition to bills that visitors brought from other parts of the country.[2]

With as many as 1,500 private banks in the United States printing their own bills, counterfeiting was rampant.[3] After all, the chaotic currency system made it a relatively easy task. False bills could be deemed “spurious” or “altered,” the former indicating that they were pure fakes, and the latter referring to real bank notes with written-in markups.[4] Beyond fabricating known bills, some counterfeiters would make up fake banks, hoping that they could successfully pass a false bill to someone else. In the slang of the time, this was known as “shoving the queer” (My favorite headline comes from an 1862 edition of the National Republican, a D.C. rag which started publication when Lincoln was elected President in 1860. It reads: A “Shover of the Queer” Nabbed—Over $400 in Counterfeit Notes and Coins Seized—The Shover Committed to Jail.)[5]

While the bank system was decidedly exploited by people who profited from fake money, it was also broken from within. Just as the design on paper bills varied widely, so did the reliability of private banks: many did not have the capital to back up their money. Without standardization, the use of paper bank notes sometimes resembled a barter system, where low-mark bills from trustworthy banks were considered more valuable than high-ticket bills from bad banks.

Indeed, suspicion was so high that banks and individuals would employ popular counterfeit detectors, which were guides that listed and described all of the known banks and bogus bills. The onus to prevent scamming fell to individuals, so most paper money was treated with skepticism. According to the Department of the Treasury, “In 1839 one guide listed 20 issues of fictitious banks; 43 banks whose notes were counterfeited; and descriptions of 1,395 counterfeit notes in circulation.”[6]

Stories about counterfeit money were common news in local publications. In 1846, the Alexandria Gazette published the tale of a local clerk’s experience with spurious bank notes. For reference, the protagonist’s name is Ike. The article begins: “It is a common saying in this region, when an individual makes a sad mistake either about his own powers in any matter, or those of an antagonist, that he finds himself ‘picked up.’”[7] One day, a stranger approached Ike asking him to swap a $10 bill from the bank of Missouri for smaller change. Seeing no apparent problem, Ike accepted, exchanging the Missouri note for his own Indiana bills. The stranger left and a friend came up to Ike, insisting that the Missouri bill was counterfeit. According to the account, “His first impulse was to tear the spurious bill; but, on second thoughts, he carefully folded it up, and let off his wrath by stirring up the hands, individually and collectively.”

But, Ike’s story didn’t end there. Soon, he was approached again, this time by a gentleman looking to change a $20 Philadelphia bill. Eager to jump on the opportunity, Ike passed the man the counterfeit and a $10 gold coin. Nonetheless, when Ike went to the bank, he found himself once again duped: according to Presbury’s counterfeit detector, the Philadelphia bill was also a “well known counterfeit.”[8] As a result, the story ends with a protagonist that is poorer, wiser, and likely more suspicious. Whether it be pure fact or moral parable, this anecdote reflects the proliferation of counterfeit money, and the complications of a system with so many different bank notes.

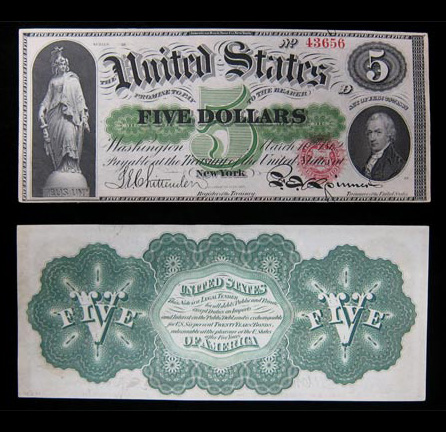

By the early 1860s, the government pushed to standardize paper money, issuing “greenbacks” by order of the Legal Tender Act to fund the Civil War and passing the National Currency Act in 1863.[9] For the first time in United States history, paper money was nationalized.

Of course, counterfeiting did not stop with only one type of paper money to rip off. Indeed, the 1860s saw astounding levels of counterfeits: anywhere between one half and one third of all printed bills were false.[10]

With so many fake bills floating around the country, the government decided to take action. Secretary of the Treasury Hugh McCulloch suggested that President Lincoln create a new federal law enforcement agency to combat the rampant problem. In agreement, Lincoln allegedly replied, “I think you have the right idea, Hugh, you work it out your own way.”[11]

McCulloch’s “way” was to create the U.S. Secret Service. (Yes, THAT Secret Service.) While today the agency is best known for protecting important political dignitaries, the Service was originally conceived to defend the integrity of U.S. currency by investigating and stopping counterfeiting. By the time the Secret Service took on protective duties in 1901, not one but three presidents were assassinated.

One of those, of course, was Lincoln himself. According to lore, the legislation that created the Secret Service was sitting on Lincoln’s desk, waiting to be signed when the President went to Ford’s Theatre on April 14, 1865. Though he didn’t live to see it, the agency was officially created on July 5, 1865 when Chief William P. Wood was sworn in by McCulloch. At that point, Secret Service personnel were commissioned in eleven districts throughout the country, from New York to St. Louis to San Francisco.[12]

In September of 1865, the Alexandria Gazette reported on the progress of the Secret Service: “The multiplicity of counterfeits of the U.S. postal currency and small notes, has attracted the attention of the government. The secret service division of the solicitor’s office has been informed of the arrest of several persons engaged in counterfeiting. One man was taken who had on his person five hundred $1 United States notes. Arrests are continually being made all over the country.”[13] According to historian Gregory Matusky, the new agency was very successful in its first year, arresting over 200 counterfeit peddlers, and taking hundreds of thousands of dollars’ worth of fake money out of circulation.[14]

Upon hiring its second chief, Herman C. Whitley, the Secret Service grew more successful as it began working alongside local law enforcement. As the National Republican noted on August 20, 1869: “a better state of feeling has been brought about, and we shall expect the city to be swept clean of the small and large dealers of counterfeit money.”[15]

Of course, it is likely that no city has ever been fully “swept clean” of counterfeiting efforts (check out this Washington Post Article from 2016 to learn how counterfeiting has been outsourced to Peru in the last decade.) While the Secret Service was transferred from the Department of the Treasury to the Department of Homeland Security in 2003, the legacy of the Free Banking Era lives on through the agency’s less-talked about mission—to protect and investigate U.S. currency.

Footnotes

- ^ Stephen Lynn Goldsmith, “Symbols on American Money,” Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia, May 22, 2007, https://www.philadelphiafed.org/education/teachers/publications/symbols-on-american-money/.

- ^ Weekly National Intelligencer. October 9, 1852. Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers, Lib. of Congress, https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn83045784/1852-10-09/ed-1/seq-8/.

- ^ Gregory Matusky. The U.S. Secret Service. (New York: Chelsea House, 1988), 22, https://archive.org/details/ussecretservice0000matu.

- ^ Bill Kemp, “Counterfeit money was a major problem in the 1850’s,” The Pantagraph, June 25, 2013, https://www.pantagraph.com/news/local/counterfeit-money-was-a-major-problem-in-the-s/article_0e46cc92-bcd4-11e1-a21e-0019bb2963f4.html.

- ^ The National Republican. January 27, 1862, Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers, Lib. of Congress, https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn82014760/1862-01-27/ed-1/seq-3/.

- ^ United States Secret Service, Excerpts from the History of the United States Secret Service 1865-1975, (Michigan: University of Michican Library, 1978), 6, https://archive.org/details/historyussecretser1978dept/mode/2up?q=one+half.

- ^ Alexandria Gazette. August 12, 1846, Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers, Lib. of Congress, https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn85025007/1846-08-12/ed-1/seq-4/.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ W. A. Richardson, National Currency Act with Amendments 1884-’72. United States Treasury Department, (Washington: Govt. Printing Office, 1872), 15, https://archive.org/details/nationalcurrenc00statgoog/mode/2up.

- ^ For one-half see United States Secret Service, Excerpts, 8. For one-third see Lucas Downey, "Wildcat Banking," Investopedia, March 5, 2020, https://www.investopedia.com/terms/w/wildcat-banking.asp#:~:text=Wildca….

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Ibid, 8-9.

- ^ Alexandria Gazette. September 14, 1865, Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers, Lib. of Congress, https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn85025007/1865-09-14/ed-1/seq-2/.

- ^ Matusky, Secret Service, 25.

- ^ The National Republican. August 20, 1869, Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers, Lib. of Congress, https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn86053571/1869-08-20/ed-1/seq-4/.

![Sketch of the mythical fuan by Pearson Scott Foresman. [Source: Wikipedia]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2023-10/Goatman_Wikipedia_Faun_2_%28PSF%29.png?h=64a074ff&itok=C9Qh-PE1)