The Centuries-Long Saga of the ‘Oyster Wars’

The battle lasted about half an hour,[1] and when the smoke cleared, Captain Frank Whitehurst lay dead in a pool of his own blood on the deck of the Albert Nickel, a Baltimore oyster schooner.[2] While Whitehurst met a fate avoided by most, the so called “Oyster Wars” had been brewing for more than 100 years prior to that fateful night on the Severn River.

Oysters have long been serious business in the Chesapeake region. In 1785, George Washington invited representatives from Maryland and Virginia to Mount Vernon so they could discuss among other things, fishing in their shared waters.[3] The resulting 13-point Maryland–Virginia Compact of 1785 included provisions about fishing rights and boat access in the Chesapeake Bay and Potomac River. The Compact also stated that “all laws and regulations” regarding the Potomac “shall be made with the mutual consent and approbation of both states.”[4]

There was just one problem: despite the Compact, Maryland and Virginia seldom acted in tandem when it came to oyster policy in their waters. And, as the economics of oysters boomed in the 19th century, the waters of the Chesapeake and its tributaries raged with competition and conflict — some of which turned violent, as Whitehurst could attest.

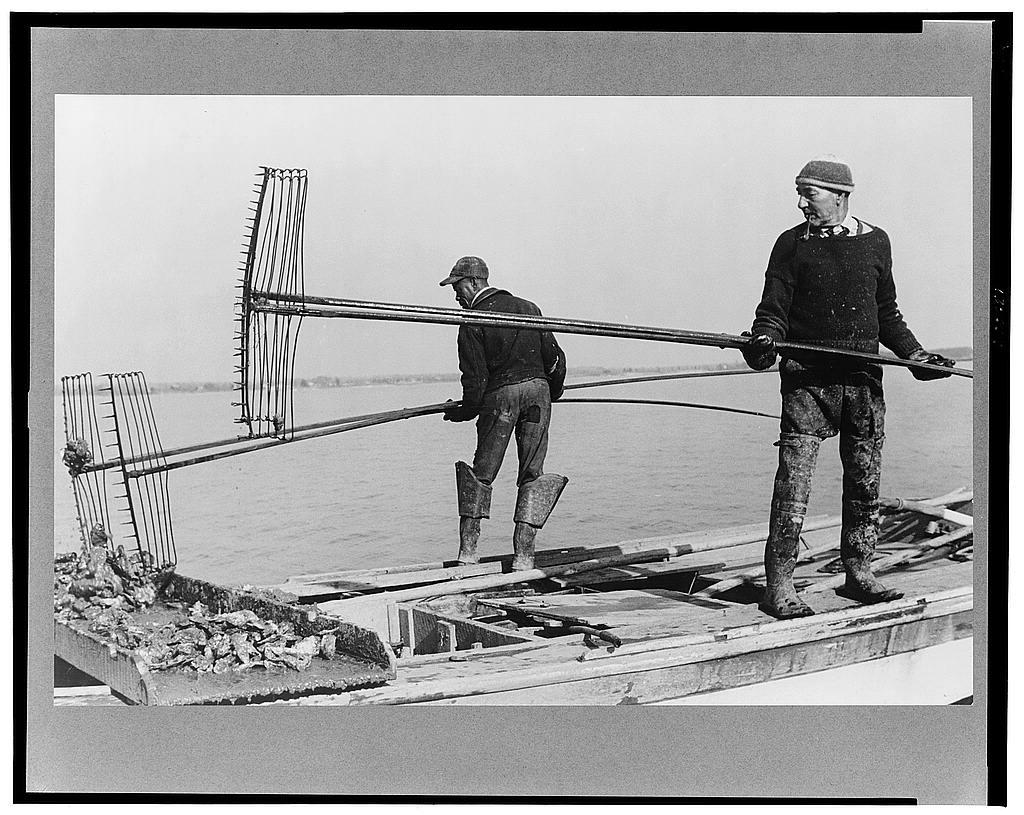

The strife began in the early 19th century when “dredging” replaced tonging as the oyster harvesting method of choice. Whereas tonging used a long metal or wooden set of rakes to reach down and collect oysters, dredging dragged a net or basket behind a boat and allowed oystermen to scrape mollusks off the bottom. Dredging was a more efficient method for catching oysters, but that efficiency led to overharvesting. The nets and baskets also scraped oyster reefs and destroyed some of them.[5]

By the 1810s, dredging was depleting oyster reefs in New England. As a result, some of those oystermen started coming to Maryland and Virginia to harvest oysters.[6] In response, Virginia passed “an Act, to prevent the destruction of Oysters within this Commonwealth” in 1811. It prohibited using “any drag, scoop or rake, or other instrument, except tongs,” to harvest oysters in Virginia waters.[7] The legislation only spurred the regional conflict by sending more dredgers into Maryland.[8] Nine years later, the Maryland General Assembly passed “An Act to prevent the destruction of Oysters in this state.” It banned residents of other states from harvesting oysters in Maryland waters, and it also outlawed dredging — oysters could only be harvested with tongs or rakes — and offenders faced a $20 fine.[9]

As stern as the new laws were, they were hard to enforce since lawbreakers generally outnumbered the authorities. At the same time, the region’s appetite — dietary and economic — for oysters was exploding. In 1839, 700,000 bushels of oysters were harvested in Maryland. By the 1850s, that number doubled.[10]

Canning technology made it possible to preserve oysters long enough to send them to faraway markets.[11] By the late 1850s, some estimates suggest Baltimore produced at least four million bushels of canned oysters annually. The country’s railroad boom made it easier, cheaper, and faster to send oysters across the country, further propelling the industry in the second half of the century.[12]

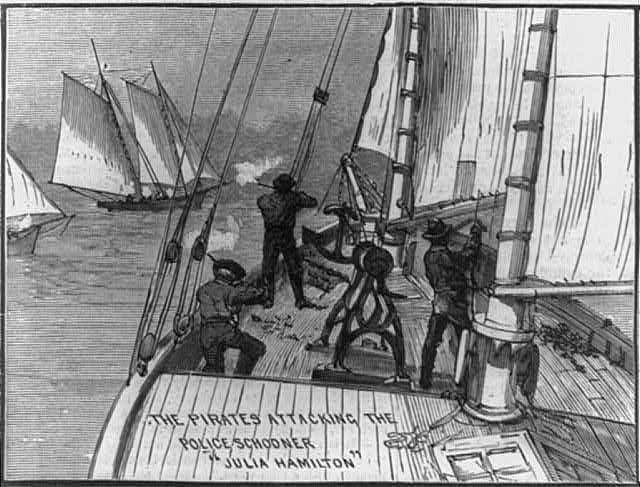

With such tremendous economic fortunes at stake, illegal harvesting was rampant and watermen clashed in multiple directions: locals and interlopers; tongers and dredgers; Marylanders and Virginians; law abiding watermen and pirates.

“It was a melee,” historian John Wennersten told The Washington Post in 1989. “It involved everyone. Sometimes it was watermen against the police, sometimes it was waterman versus waterman.”[13]

Meanwhile, Virginia and Maryland were at odds over boundaries and which state owned the rich fishing grounds of Tangier Sound, in the Chesapeake Bay.[14]

In an attempt to restore order and crack down on rampant illegal harvesting, Maryland created the State Oyster Police Force on March 30, 1868. The commissioners of the force were given $22,000 — about $622,000 today — to buy one steam-powered vessel and two other boats. They were also authorized to buy arms and ammunition.[15]

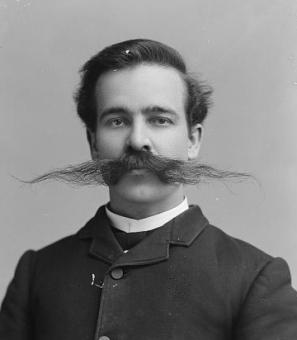

Naval Academy graduate and Civil War veteran Hunter Davidson was appointed as the first commander of the Force, which became known as the “Oyster Navy.”[16] He was “required to keep his vessel constantly cruising, when circumstances will permit, wherever opposition to the oyster law has arisen, or is likely to arise, within the boundaries of the State, and that every locality where a violation of the law exists, or is likely to arise, shall be visited as often as the duties of the force and the conditions of the vessel will permit.”[17]

A 1,450-pound cannon capable of firing 12-pound cannonballs was among the arms purchased for the Police Force. In 1868, Davidson put the cannon on the Leila, the Oyster Navy’s steam vessel.[18] Despite its size, the cannon didn’t seem to scare off the oyster pirates.

In his 1870 report, Davidson got right to the point. “None of the laws relating to it have provided any adequate means for its protection,” he wrote. He went on to say he thought fishermen would continue to break the laws unless the punishment was “greater than the inducement to do so.” The commander further noted that fishermen who routinely broke the laws were tracking the Oyster Police’s movements in order to evade detection.[19]

Virginia’s 1811 law clearly wasn’t working, so in 1880, the General Assembly passed “an Act to prohibit the catching of oysters with dredges or instruments other than ordinary oyster-tongs within the waters of the commonwealth.” The law explicitly banned dredging, but it did little to calm the waters.[20] Many simply ignored the new law, much to the ire of law-abiding “tongers.”[21]

Early in the morning of Feb. 17, 1882, Virginia Gov. William Cameron decided to take matters into his own hands. Leading a “two vessel navy” made up of members of his staff, and some local militia members, he set off on a mission against illegal oyster harvesters in the Rappahannock River. After a few hours, Cameron’s crew spotted seven vessels they suspected of illegally dredging for oysters near the mouth of the river. Cameron’s ships were able to get close to the oyster boats by acting as if the larger ship in Cameron’s fleet was towing the second one back to shore. Then, they attacked and captured six of the oyster boats. One tried to escape, but after a three-hour chase, the crew surrendered to Cameron’s forces.[22]

At first, Cameron’s mission was deemed a success. The captured oystermen were each sentenced to one year in prison, and all seven boats went to auction where their owners had to repurchase them,[23] in accordance with the 1880 law.

However, bowing to political and editorial pressure (many of the accused were from Virginia’s Eastern Shore), in April 1882, Cameron reduced the captains’ sentences to six months each, and he pardoned one who was ill. He also pardoned the oystermen — except for one who set the jail on fire in an escape attempt. In November, the Virginia Supreme Court ruled that the boat owners had not been fairly represented and they should be refunded from having to buy back their boats. To make matters worse, illegal oyster dredging continued, and many of the men Cameron pardoned were back out on the water.[24]

Desperate to redeem himself, Cameron waged another expedition in February 1883, but once again, he was largely unsuccessful. To add chauvinistic insult to injury, the governor was mocked when word got out that the Dancing Molly, a boat he tried to capture was actually commanded by three women and they managed to outrun his forces. Cameron had allowed a reporter from the Norfolk Virginian to accompany his forces on this mission. The reporter published his account of the events and it was quickly reprinted in papers across the state.[25] The incident also became the subject of a comic opera that was performed in Norfolk that spring.[26]

In 1884, Cameron reinstated the Virginia oyster navy, but despite early successes, the force was largely unable to control illegal oyster harvesting in the state in the decades to come.[27]

In addition to overharvesting, dredging also destroyed oyster reefs, and local harvests began to decline in the early 1900s,[28] but on and off Oyster War skirmishes continued in both Maryland and Virginia well into the 20th century.

As The Washington Post noted with some resignation in 1947, “Possibly a man is dead, perhaps a boat is taken, but the oyster war will go on the next night and the next.” The paper continued, “Three factors contribute to the situation: the ancient pact between Virginia and Maryland, the failure of Virginia to enforce her laws and the failure of both States to enact modern legislation to maintain and protect the Potomac fisheries.”[29]

The situation finally reached a head in April 1959. Berkeley Muse and two other people were suspected of illegally dredging for oysters near Swan Point on the Maryland side of the Potomac River early in the morning of April 8. When patrol boats spotted them and began to approach, the three men sped off towards Virginia. The Maryland patrollers began shooting. Muse died from his wounds, and one of his companions was hit in the leg, but survived. Virginia state police didn’t find any dredging equipment on the boat and determined the men had been tonging for oysters that night.[30]

“The tragedy resounded almost immediately in the Virginia General Assembly where the Senate was set to consider approval of a bi-state compact designed to end the long Maryland-Virginia ruckus over fishing rights,”[31] The Washington Post reported on April 9.

The Virginia and Maryland legislatures both adopted the 1958 compact, but in order to enact it, the compact first had to go through a statewide referendum in Maryland. It passed and went to Congress for ratification. In December 1962, President John F. Kennedy signed the legislation, and the Potomac River Fisheries Commission was formed.[32] Over a century after they began, the Oyster Wars were officially over.

Footnotes

- ^ “Indignant Oyster Dredgers,” The Washington Post, February 21, 1888.

- ^ “An Oyster Pirate Killed,” The New York Times, February 20, 1888.

- ^ “Mount Vernon Conference,” George Washington’s Mount Vernon, https://www.mountvernon.org/library/digitalhistory/digital-encyclopedia….

- ^ “Maryland-Virginia Compact of 1785,” Chapter 27 § (1786).

- ^ Kathy Warren, “The Infamous Oyster Wars,” SOMD This Is Living, July 29, 2019, https://somdthisisliving.com/peopleplaces/community/the-infamous-oyster….

- ^ Ann Powell, “Oyster Wars Cannon at the Annapolis Maritime Museum,” Annapolis Discovered, February 21, 2019, https://annapolisdiscovered.com/oyster-wars-cannon-at-the-annapolis-mar….

- ^ “Acts Passed at a General Assembly of the Commonwealth of Virginia. 1808-1812suppl. 1812.,” HathiTrust, https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=osu.32437123258820&view=1up&seq=….

- ^ Victor Kennedy and Linda Breisch, “Sixteen Decades of Political Management of the Oyster Fishery in Maryland’s Chesapeake Bay,” JOURNAL OF ENVIRONMENTAL MANAGEMENT 164 (1983): 153–71, https://www.mdsg.umd.edu/sites/default/files/files/16_Decades.pdf.

- ^ “Laws of Maryland Made and Passed at a Session of Assembly. 1820-1821 1820-1821.,” HathiTrust, https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=osu.32437123280527&view=1up&seq=….

- ^ Henry Miller, “The Oyster In Chesapeake History,” https://www.hsmcdigshistory.org/pdf/Oyster.pdf.

- ^ “On the Water - Fishing for a Living, 1840-1920: Commercial Fishers > Chesapeake Oysters,” americanhistory.si.edu, https://americanhistory.si.edu/onthewater/exhibition/3_5.html.

- ^ David M Schulte, “History of the Virginia Oyster Fishery, Chesapeake Bay, USA,” Frontiers in Marine Science 4 (2017): 127, https://doi.org/10.3389/fmars.2017.00127.

- ^ Howard Schneider, “IN WINTER OF 1889, OYSTER WARS CHURNED THE CHESAPEAKE,” The Washington Post, October 12, 1989, https://www.washingtonpost.com/archive/local/1989/10/12/in-winter-of-18….

- ^ Howard Schneider, “‘In the Winter of 1889, Oyster Wars Churned The Chesapeake”

- ^ “STATE OYSTER POLICE FORCE,” March 30, 1868, https://dnr.maryland.gov/Documents/OysterPoliceAct_1868.pdf.

- ^ Mark Belton, “Hunter Davidson: Maryland Oyster Police Force,” The Southern Maryland Chronicle, March 30, 2018, https://southernmarylandchronicle.com/2018/03/30/hunter-davidson-maryla….

- ^ “STATE OYSTER POLICE FORCE”

- ^ Ann Powell, “Oyster Wars Cannon at the Annapolis Maritime Museum”

- ^ Hunter Davidson, “Report Upon the Oyster Resources of Maryland” (Annapolis: WM Thompson, 1870).

- ^ Acts and Joint Resolutions passed by the General Assembly of the State of Virginia during the Session of 1879-80. (Richmond, 1880), https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=uva.x030211324&view=1up&seq=208&….

- ^ Anna Gibson Holloway, “‘The Pirate-Dredger’s Doom’: Politics and Pirates on the Chesapeake Bay, 1882-1883,” 1994.

- ^ James Tice Moore. "Gunfire on the Chesapeake: Governor Cameron and the Oyster Pirates, 1882-1885." The Virginia Magazine of History and Biography 90, no. 3 (1982): 367-77.

- ^ James Tice Moore. "Gunfire on the Chesapeake: Governor Cameron and the Oyster Pirates, 1882-1885."

- ^ James Tice Moore. "Gunfire on the Chesapeake: Governor Cameron and the Oyster Pirates, 1882-1885."

- ^ Anna Gibson Holloway, “‘The Pirate-Dredger’s Doom’: Politics and Pirates on the Chesapeake Bay, 1882-1883”

- ^ “Chesapeake Bay - Oyster Wars - The Mariners’ Museum,” www.marinersmuseum.org, 2002, https://www.marinersmuseum.org/sites/micro/cbhf/oyster/mod006.html.

- ^ James Tice Moore. "Gunfire on the Chesapeake: Governor Cameron and the Oyster Pirates, 1882-1885."

- ^ David M Schulte, “History of the Virginia Oyster Fishery, Chesapeake Bay, USA”

- ^ F.B. Rhein, “‘Oyster War’ Is Livelihood vs. Law,” The Washington Post, November 9, 1947.

- ^ J.W. Anderson and Laurence Stern, “Virginian Killed in Oyster Feud,” The Washington Post, April 9, 1959.

- ^ J.W. Anderson and Laurence Stern, “Virginian Killed in Oyster Feud”

- ^ Potomac River Fisheries Commission, “Potomac River Fisheries Commission - HISTORY/MISSION

![Sketch of the mythical fuan by Pearson Scott Foresman. [Source: Wikipedia]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2023-10/Goatman_Wikipedia_Faun_2_%28PSF%29.png?h=64a074ff&itok=C9Qh-PE1)