Hulks like Huge Flower Pots: The Ghost Fleet of Mallows Bay

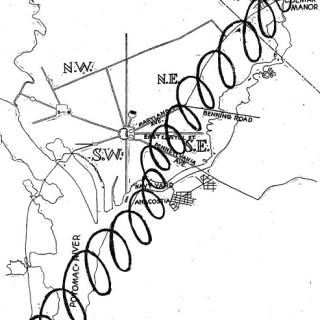

Picture this: you’re traveling down the Potomac River, going south of Washington, D.C. The cityscape disappears behind you as you float away. Small towns and buildings show up here and there, but some creeks and coves remain as they have been, preserved as state parks or nature reserves. As you continue further down the wide river, about 40 miles from Washington, something out of the ordinary pops up: a wooden stake with large nails sticking out of it. The stake is surrounded by others and seems to form the shape of something. Further down you notice an island jutting off the shoreline. As you investigate, you realize that this is no naturally made island; it is a partially sunken ship. Covered in trees and other greenery, this island is not alone, and dozens more of similar shapes surround it.

Welcome to the Ghost Fleet of Mallows Bay.

It all started with World War I. By the beginning of 1917, the United States was not yet at war, but it was becoming increasingly clear that U.S. involvement was imminent. German U-Boats were destroying the world’s merchant vessels at an unprecedented rate of more than 200 a month, with one in four English ships ending up on the ocean floor.1 In order to offset the allied losses to these enemy submarines, the United States decided to build its own set of water vessels in hopes of stopping German interference. However, this was not going to be an easy feat. Merchant shipping hadn’t been a priority in America since the Civil War and the U.S. had come to rely on the use of foreign ships, primarily British, to transport most of its sea commerce.2 In order to create the necessary ships, the United States would have to start its shipbuilding effort essentially from scratch.

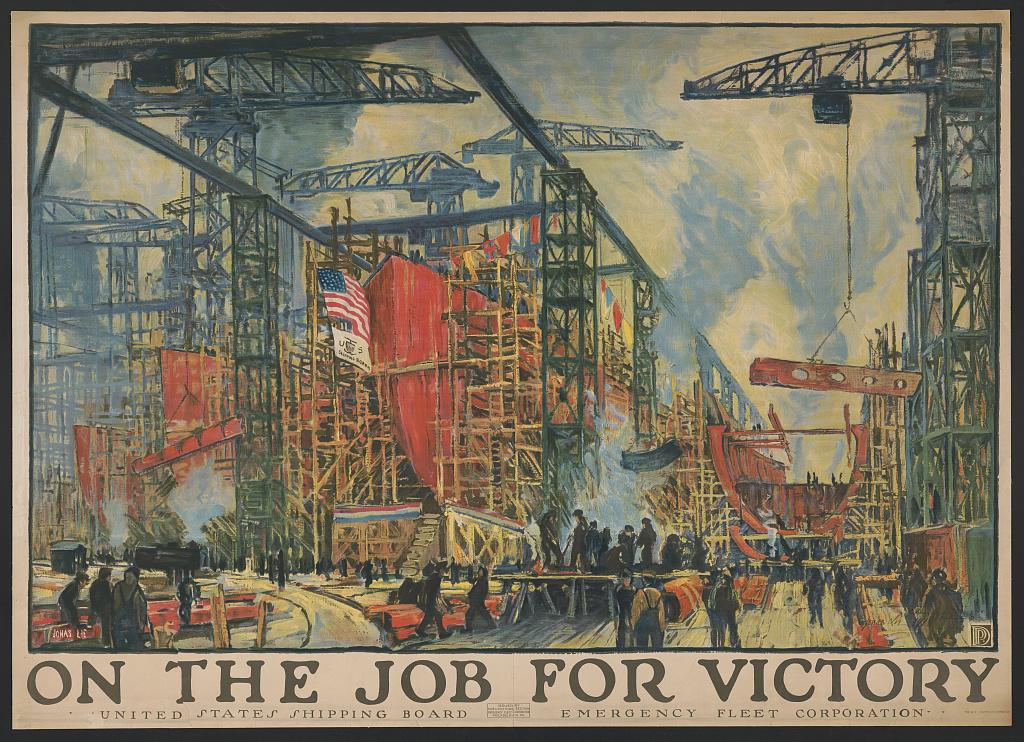

But these small details didn’t stop the United States government from pursuing the largest shipbuilding effort in American history.3 With President Wilson’s declaration in April 1917, the U.S. was officially at war. And one of the President's first wartime initiatives was to create the Shipping Board, and in turn, the Emergency Fleet Corporation.4 From the beginning, the goals of the Shipping Board were incredibly aspirational. Appointed Chairman William Denman, proudly announced within days of the U.S.’ entry into WWI that the Emergency Fleet Corporation would build 1,000 ships in 18 months. Denman claimed that they would build “a bridge of ships from New York to Liverpool.”5

The reason that Denman believed that so many ships could be built so quickly was because of the wide availability of wood. Though steel had surpassed wood as the material of choice for shipbuilding, the reach of destruction from the German submarines meant that all ships were needed, and they were needed quickly.6 So, the U.S. got to planning a new fleet of wooden steamships to supplement the nation’s supply of steel ships.7 With plenty of lumber reserves seemingly on hand, how long could it possibly take to build a ship?8 The answer? Too long.

The optimism of the Shipping Board dwindled almost immediately once it fully examined its collection of resources. Not only was there not as much seasoned lumber as initially anticipated, but another key component was also in short supply: shipbuilders.9 Additionally, they were challenged with inconsistent leadership, causing “national controversy” and negative attention.10 However, despite these early challenges, the Emergency Fleet Corporation persevered, and shipyards began to pop up across the nation, with 189 different companies in 26 different states participating in the shipbuilding effort. These crews were building ships in record time too, just as was promised.11

Not everyone was as enthusiastic about the ships that were being produced, however. It soon became clear that the quality of the ships was not what it needed to be to cross the Atlantic. Presciently, New Hampshire Senator Jacob H. Gallinger declared that “...when the war closes, whether it be within one year or five years, we shall have a lot of worthless ships on our hands that will have cost this country an enormous amount of money.”12

Gallinger’s assessment was a bit harsh, but not far off from the truth – and made worse by the fact that the ships that were being built were way over budget.13 And, on November 11, 1918, another part of his prophetic statement came true. Germany surrendered, and the First World War ended before a single one of the wooden ships built under the Emergency Fleet Corporation had made it to a European port.14 The U.S. had become the world’s leading shipbuilder for the first time in history, although hardly any of the ships had been used for their intended purpose.15

The federal government was disappointed with the effort and endured constant criticism. Days after the Armistice was signed, there was a call for a full congressional investigation into the Shipping Board led by then-Senator Warren G. Harding.16 With increased negative attention, the U.S. wanted nothing to do with the ships anymore and hastily tried to get rid of them. All over the country, the government began to sell the ships at a significant financial loss, just to see them gone.

The largest group of castoff ships – some 233 – were anchored in the James River in southern Virginia.17 Purchased by a San Francisco attorney for pennies compared to what the ships had cost to build, he intended to scrap them for parts. While the ships had received so much attention for their wooden structure, it was the steel supports and machinery that had value.18 To achieve this, the new owner turned the fleet over to the Western Marine & Salvage Company (WM&SC), a group based in Alexandria.19 WM&SC planned to tow the ships to Alexandria, take them apart, get rid of the wooden hulls, and sell the scrap metal for profit.20

However, much like what happened during the ship’s creation, WM&SC faced issues right from the start. While the company was deconstructing the ships in Alexandria, they needed somewhere to store all the fleet. The public pushed back against bringing the fleet from the James River into the Potomac. This region was considered to have some of the most bountiful fishing on the Potomac. Maryland and Virginia fishers relied on this part of the river for their livelihood and having a collection of unusable ships sitting in the way was very inconvenient.21 With public complaints, along with some instances of ships unmooring and floating down the river, the WM&SC was in a tough spot - they needed to get rid of the vessels, and they needed to get rid of them fast.22

So, they burned them.23

On November 7, 1925, the first 31 ships were lashed together with steel cables and the flotilla was set on fire, in the waters of Mallows Bay, a cove on the Potomac that was adjacent to farmland that WM&SC had purchased in 1924.24 Meanwhile, the rest of the fleet awaited their fate in other parts of the river, such as Widewater or Sandy Point. The flames would burn for hours and could be seen for miles, in what was considered the largest destruction of ships at one time in United States history.25 WM&SC would continue in years to come burning the hulls and abandoning them until Mallows Bay became crammed with the skeletons of ships.26 However, while WM&SC started this endeavor, the company would not finish it. After continued protests and financial troubles, WM&SC went bankrupt during the Great Depression, leaving over 100 half-burned and salvaged hulls sitting in Mallows Bay.27

The fleet remained largely ignored until WWII when the U.S. was once again desperate for resources, including scrap metal. The community, which had continued to view the half-burned hulls of the Bay as an eyesore, requested the government’s involvement in removing the ships – presenting the perfect opportunity for the government to collect scrap metal.28 Gambling hundreds of thousands “on the recovery of at least 11,000 tons of high-grade scrap metal by salvaging the hulks of 110 ghost ships stuck in the mud,” the federally organized Metal Reserves Company contracted the Bethlehem Steel Corporation to get to work on the ships. The group was hoping to salvage 100 tons of scrap per ship, along with an additional 5,000 tons that had fallen into the Potomac over time.29 Finally, it appeared as though “World War II may finish something that World War I had started.”30 However, what seemed to be the curse of the Ghost Fleet continued with Bethlehem Steel. Before the contracted company could strip all the ships of scrap metal, the Second World War ended, and their services were no longer needed.31 The fleet was left alone in Mallows Bay once again.

In 1964 a group of residents once more requested that the government do something about the hulls. The group expressed a familiar concern: the floating hulls were a hazard to river navigation and inhibited shoreline development.32 The ships had been a nuisance for over 40 years, and many wanted them gone once and for all. The issue reached Congress, with the House Conservation and Natural Resources Subcommittee of the Committee on Government Operations holding hearings.33

But while the debate over the ships had stretched on for decades, something fascinating was happening underwater. The ships that no one seemed to want had transformed the ecology of the area – in many ways for the better. In the Congressional hearings, various environmental groups, from the Department of the Interior to the Chesapeake Biological Laboratory spoke about the ecological benefits that the fleet of sunken ships was having on the environment in Mallows Bay.34 Over the decades, the decrepit boats had trapped various sediments and “collected plant life becoming artificial islands.”35 Many creatures had adjusted to the hulls being in the river and now relied on these structures as integral parts of their habitat.

Furthermore, some groups no longer considered the sunken hulls an eyesore, and instead were calling them “picturesque.” With additional stabilization, congressional members believed that the hulls would no longer interfere with river navigation.36 The committee report from this testimony showcased the potentially bright future of the Bay:

“Seen from the air some of the hulks look like huge flower pots. Only the outlines are visible. Over the years, trees have taken root in the earth inside the hulls, and these strange islands are not unattractive. Herons and egrets make their homes there. The American bald eagle nests in the area. The adjacent estuary is spawning ground for striped bass.”37 It was also revealed that while there might have been pollution from the ships when they were first anchored in Mallows Bay, any possible removal could potentially release those pollutants, harming the new environment that had adjusted to the shipwrecks.38

The ships were here to stay, and the State of Maryland began investing in more study of the area. In 1993, a Maryland state grant provided support to research the Ghost Fleet and its surrounding environment. In addition to the World War I boats, researchers discovered ships dating as far back as the late 18th century, along with a rich marine environment that supported a wide range of life forms.39 Later evaluations shed more light on the environment in Mallows Bay. It was discovered that some of the species living amongst the ships – such as the Longnose Gar and the Warmouth fish – were species that the state of Maryland had identified as needing greater protection. Additionally, the spotted lodgings of the once nearly extinct beaver were further proof of the environmental resurgence of the region.40

Furthermore, scientists determined that the fleet wasn’t just providing for the environment – the ships were also protecting it. The presence of the shipwrecks had actually decreased erosion rates and increased the representation of different habitats, including wetland, woodland, and aquatic areas in and out of the water.41 The positive reach of the shipwrecks went beyond the stretch of water they occupied and provided for ecologically significant land species.42

In 2019, NOAA designated the area as the Mallows Bay-Potomac River National Marine Sanctuary. It was the first national marine sanctuary designated since 2000.43 With this designation, the area and the shipwreck were protected, and in turn the diverse ecosystem they support. Now popular with kayakers, nature lovers, and historians alike, the environment continues to grow around its industrial foundation.

Finally, the Ghost Fleet of Mallows Bay had found its purpose.

Footnotes

- 1 Edward N. Hurley, The Bridge To France (Kessinger Publishing, LLC, 2004).

- 2 Donald G. Shomette, Ghost Fleet of Mallows Bay and Other Tales of the Lost Chesapeake, 1st ed. (Centreville, Md: Tidewater Publishers, 1996), 214.

- 3 Donald G. Shomette, “The Ghost Fleet of Mallows Bay,” The Natural Resource, Winter 2001.

- 4 “Will Supply Boats for U.S. Commerce,” The Evening Star, April 17, 1917.

- 5 Shomette, Ghost Fleet of Mallows Bay and Other Tales of the Lost Chesapeake, 215.

- 6 Shomette, 215.

- 7

Shomette, 214. See also The Ships of Mallows Bay.

- 8 Shomette, 215.

- 9 Shomette, 217.

- 10 Special to The New York Times, “GOETHALS RESIGNS,” The New York Times, July 25, 1917; William Denman and the Emergency Fleet Corporation’s general manager, General George W. Goethals (creator of the Panama Canal) got into a disagreement about what the ships should be built from, wood or steel, leading to both men being asked to resign and eventually replaced.

- 11

Jacob Fenston and Tyrone Turner, “The Ghost Fleet,” WAMU.

- 12 Shomette, Ghost Fleet of Mallows Bay and Other Tales of the Lost Chesapeake, 227.

- 13 Shomette, 217; At the start of the endeavor, the Shipping Board estimated that it would cost about $300,000 for each hull and $250,000 for machinery for each ship. In the end, though, each ship would cost about $750,000 to produce.

- 14

“Ghost Fleet of the Potomac, Mallows Bay | National Trust for Historic Preservation.”

- 15 Shomette, 227.

- 16 Hurley, The Bridge To France.

- 17 Shomette, Ghost Fleet of Mallows Bay and Other Tales of the Lost Chesapeake, 234; the total purchase was for 233 ships, with WM&SC receiving 218 wooden ships along with 15 other vessels.

- 18 Shomette, 235.

- 19 Shomette, 234.

- 20

- 21 Shomette, Ghost Fleet of Mallows Bay and Other Tales of the Lost Chesapeake, 236.

- 22 “DOOMED WOOD SHIPS ADRIFT IN POTOMAC MENACE TO SHIPPING: Salvage Company Notified Prescribed Protection Must Be Given. BURNING OF VESSELS HELD UP MEANTIME Details of the Wanderings of Some of World War Fleet Relics.,” The Washington Post (1923-1954), September 3, 1925.

- 23 Shomette, Ghost Fleet of Mallows Bay and Other Tales of the Lost Chesapeake, 239-241; research appears to state that initially the boats were brought up individually from the James River to the Mallows Bay/Widewater part of the Potomac. After successful burning tests and ongoing conversation, by October 1923 all 218 were in Widewater or on their way. By spring 1924, ongoing disposal problems at Widewater led WM&SC to begin anchoring the ships in Mallows Bay.

- 24

Jason Fenston and Tyrone Turner, “The Ghost Fleet,” WAMU.

- 25

“Ghost Fleet of the Potomac, Mallows Bay | National Trust for Historic Preservation;” Jacob Fenston and Tyrone Turner, “The Ghost Fleet.”.

- 26 Shomette, Ghost Fleet of Mallows Bay and Other Tales of the Lost Chesapeake, 253-254.

- 27 Office of National Marine Sanctuaries. 2016, Mallows Bay-Potomac River National Marine Sanctuary Designation Draft Environmental Impact Statement. U.S. Department of Commerce, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, Office of National Marine Sanctuaries, Silver Spring, MD; Steinbraker v. Crouse, 169 Md. 453, 182 A. 448 (Md. 1936); Steinbraker v. Crouse acknowledges that WM&SC had left 169 vessels in Mallows Bay at end of their time. The author assumes the other 64 had been dismantled entirely or sunk in other parts of the Potomac such as Widewater or Sandy Point.

- 28 Associated Press, “War Cry for Metal May Write Finish on Derelict Vessels,” The Evening Star, June 2, 1942.

- 29 Carroll E. Williams, “110 Mallows Bay Ghost Ships Will Go To War - As Scrap,” The Sun, July 11, 1943.

- 30 Associated Press, “War Cry for Metal May Write Finis on Derelict Vessels.”

- 31 Shomette, Ghost Fleet of Mallows Bay and Other Tales of the Lost Chesapeake, 275.

- 32 Peter Masley, “Ship Graveyard Stirs Charles County Protests,” Evening Star, July 7, 1964.

- 33 Shomette, Ghost Fleet of Mallows Bay and Other Tales of the Lost Chesapeake, 281.

- 34 Donald G. Shomette, “The Ghost Fleet of Mallows Bay,” The Natural Resource, Winter 2001.

- 35 Office of National Marine Sanctuaries, Mallows Bay-Potomac River National Marine Sanctuary Designation Draft Environmental Impact Statement, 73.

- 36 “Reuss to Eye Pepco Move On Potomac,” The Evening Star, July 14, 1970, 195 edition.

- 37 Shomette, Ghost Fleet of Mallows Bay and Other Tales of the Lost Chesapeake, 283-284.

- 38 Shomette, 284.

- 39

“Mallows Bay by Kayak: A Tour of Maryland’s Proposed National Marine Sanctuary, the First in Chesapeake Bay | Response.Restoration.Noaa.Gov;” this report states that 88 of the original Ghost Fleet were discovered, along with a multitude of other ships that had been left in the Bay at different points in history. Other general estimates state that there are over 200 ships in Mallows Bay, see Jacob Fenston and Tyrone Turner, “The Ghost Fleet”.

- 40 Shomette, Ghost Fleet of Mallows Bay and Other Tales of the Lost Chesapeake, 324.

- 41 Office of National Marine Sanctuaries, Mallows Bay-Potomac River National Marine Sanctuary Designation Draft Environmental Impact Statement.

- 42 Office of National Marine Sanctuaries.

- 43 Jacob Fenston and Tyrone Turner, “The Ghost Fleet.”

![Sketch of the mythical fuan by Pearson Scott Foresman. [Source: Wikipedia]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2023-10/Goatman_Wikipedia_Faun_2_%28PSF%29.png?h=64a074ff&itok=C9Qh-PE1)