Remembering Kit Kamien

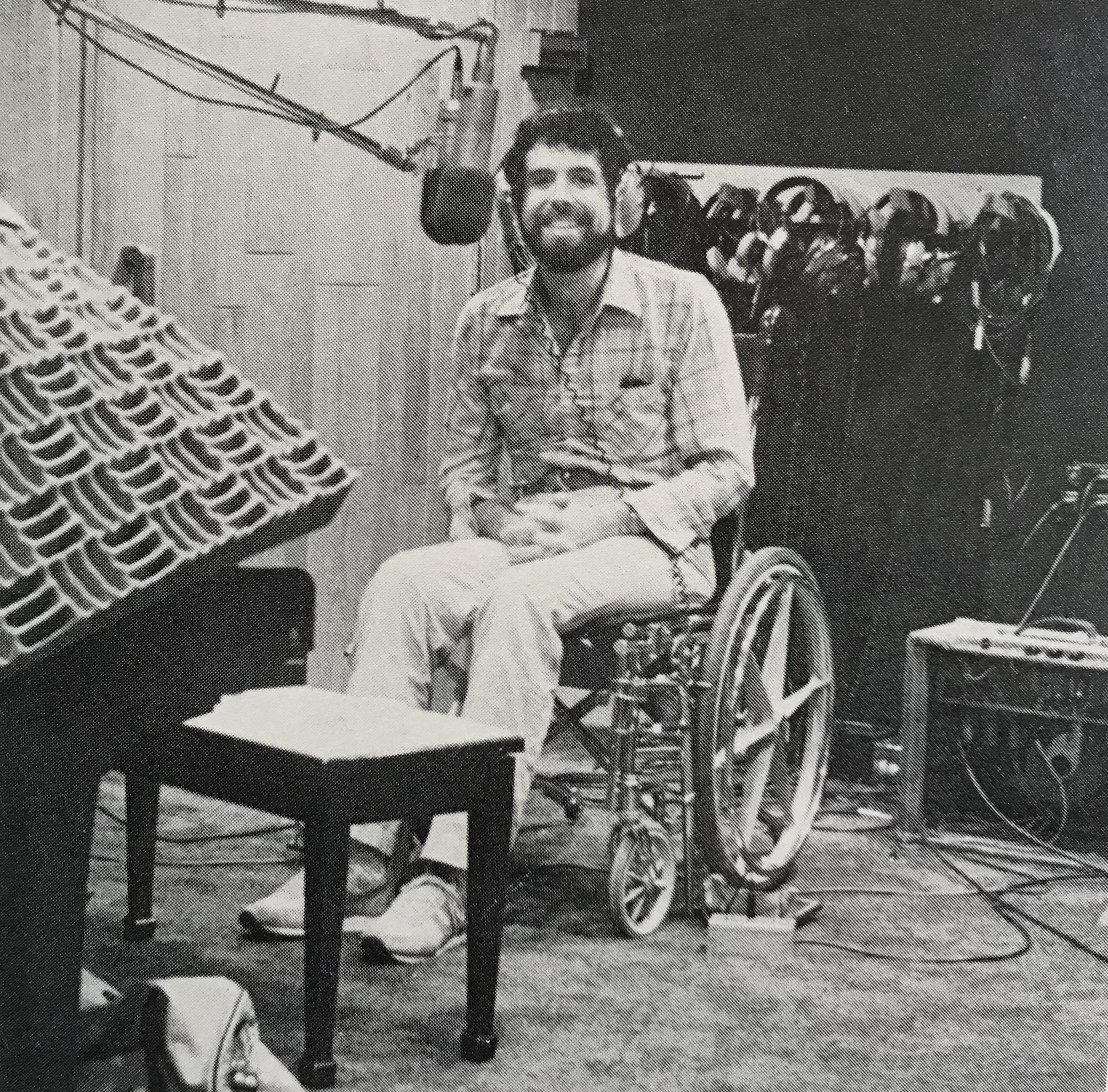

“It’s more of a tragedy if you don’t get up and do something,” remarked Kit Kamien, a Bethesda musician who had been diagnosed with multiple sclerosis, to The Washington Post in 1981.[1]

Multiple sclerosis (often shortened to MS), is a chronic disease of the immune system, which causes an abnormal response against the central nervous system. This response causes damage to myelin, which is the coating that protects nerve fibers. As a result, patients with MS can have myriad symptoms, including dizziness, vertigo, double vision, numbness, fatigue, stiffness and muscle spasms.[2]

Kamien first experienced symptoms in 1978 at the age of 26, when he was performing at a concert. He had trouble using his foot to flip the switch that gave power to his amplifier. After another incident where he was seeing double, he visited the doctor, which led to the conclusion that he had MS.[3] Over time, his condition would cause weakness in his body, making it difficult for him to pick things up, walk, or play the guitar.

The musician recalled: “At first I wanted my friends to suffer as much as I was—to have as much trouble doing laundry, shopping for groceries or just going up and down steps … But my friends wouldn’t take it. They kept me from withdrawing or taking myself too seriously.”[4]

The music scene that Kit Kamien grew up in requires a bit of background for those of us who weren’t there. To borrow the words of music writer and Post staffer Richard Harrington, a “counterculture wellspring” began percolating locally in the late 1960s, crafting a particularly happening hub for music for about twenty years.[5] The music styles: rock, bluegrass, hard-core punk and the burgeoning new wave. The heart of this hub: Bethesda, Maryland.

While few bands from this scene became commercially successful or nationally famous (though you may have heard of the Nighthawks, Root Boy Slim or Danny Gatton), there were many opportunities for local bands to play original music at venues and on the radio.

In particular, the station WHFS (102.3 FM) was a humble but mighty cultural hub, delivering mainstream and obscure tunes to local airwaves. According to actor Daniel Stern, WHFS did more than broaden musical horizons. He said: “The WHFS ethos was showing me the way to be different, the way to be myself, take chances, overturn rocks, slow down and be subversive.”[6] Despite being too small to appear in Arbitron ratings, WHFS hosted the likes of Mick Jagger, Linda Ronstadt, Jimmy Buffett, Stevie Nicks and more.[7]

Across the street from WHFS on Cordell Avenue was the Psyche Delly, a deli-turned music venue with a capacity of 90. As a Bethesda Magazine article entitled “When Bethesda Was Cool” describes: “In late 1974, owner Lou Sordo began hosting local musicians, transforming the Delly into an ear-crunching musical venue at night. There was a small, low stage in the back, a nondescript food counter toward the front, and a mismatched assortment of rock and roll—and beer—related wall hangings.”[8]

Richard Harrington described that Delly concert-goers would “crowd into a long, narrow room that smelled of closeness and shook with elect[r]ic vibrations and somehow share dreams and aspirations and stories about life on the road, even when that road was just a Beltway.”[9] Before July of 1982, the local (legal) drinking age was 18, so young people were a major contingent in the nightlife scene.

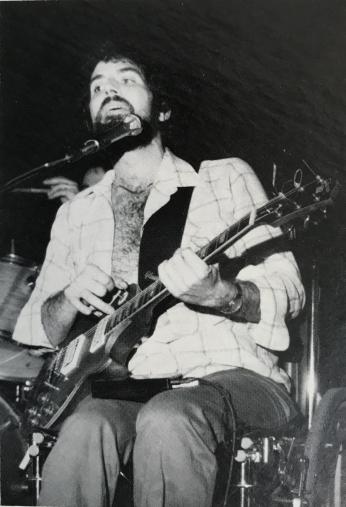

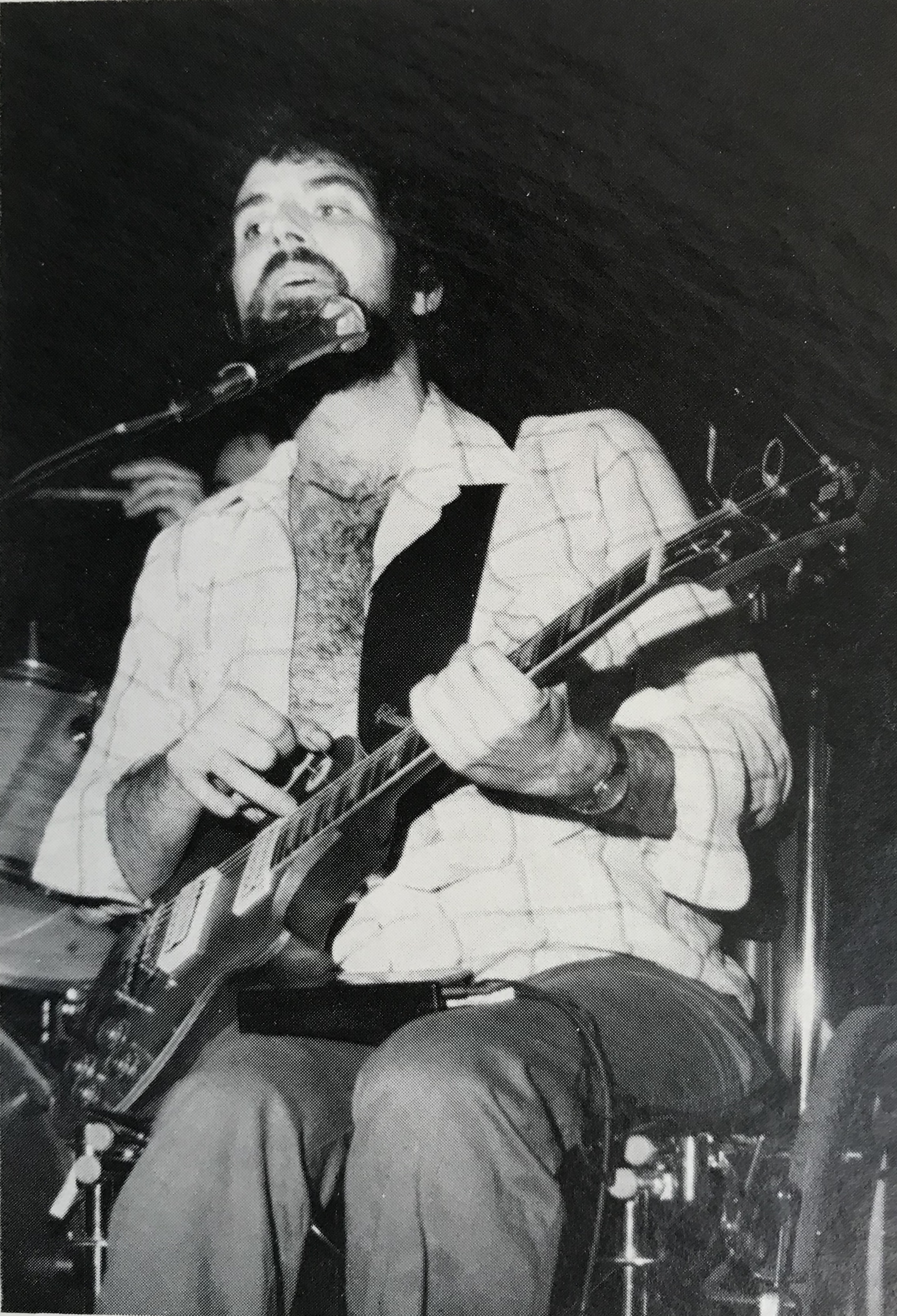

According to The Unicorn Times—an independent music-focused newspaper published in Washington, D.C. from 1973 to 1985—Kit Kamien was a regular performer at the Psyche Delly, at the young age of 22. Kamien’s name appears on several 1974 segments of “Who’s Appearing Where.”[10]

Riki Schneyer, a visual artist and musician currently based in Maine, had a close friendship with Kamien, which began in their early teens when they met at a party. In a phone call, she described Kit as a “very vital, brainy, creative person,” a “brilliant guitarist and remarkable spirit,” and as “one of the funniest people” she’s ever known.

Schneyer painted the Psyche Delly as a “dark, teenaged, underground cave,” yet an integral part of the “wonderful, rich, creative scene” in Bethesda. She described Kit as tall and gangly, with big, bushy hair and a beard, and said that before he used a wheelchair, he “loved to make a dramatic entrance” when he would perform. She laughed, struggling to describe a theatrical bit where he would have a woman wearing a nurse’s outfit (often Schneyer herself) escort him to the stage. She remarked: “He was a giant imp with a huge heart.”

As of 1981, Kamien’s MS made it too difficult for him to perform, but he still found ways to keep music in his life: he taught the guitar and electric bass to locals, produced records, and began planning an album. When his condition made him lose feeling in his fingers, he plotted out songs using a Casio computerized music keyboard and had other musicians execute the instrumentation that he didn’t have the mobility to do himself.[11]

In October of 1982, Kamien underwent an experimental chemotherapy treatment that allowed him to play the guitar again. A Washington Post article declared that he would be making a comeback for a free concert on June 27, 1983 at Fort Reno Park in Tenleytown.[12]

In Kamien’s eyes, the chemotherapy treatment had pros and cons. He said:

“[It has] shades of gray—for instance, I’m still in a wheelchair. And all of your hair falls out, and that’s kind of bad on your self-esteem when everybody tell[s] you you look like Telly Savalas and you can’t stand Telly Savalas. But I’ve been able to cope, to get around a lot of problems. On the positive side, I can feel my fingers, I can tie my shoelaces and button my shirt up. My sense of balance is still trashed from the MS, which is why I still use a wheelchair, but my muscle strength has really gotten a lot better, and my stamina is a real mind-blower—I’ve been able to outlast most of my friends.”[13]

In the mid-1980s, he released an 11-song LP entitled “Kit Kamien and The Backroom Players”— a bluesy rock album driven by its witty, offbeat lyrics. Every song was written, arranged and produced by Kamien himself, aside from two borrowed blues tunes, “Shake a Tail Feather” and “Nadine.” Its major theme is frustration, which manifests both in failed romance and physical disability. In terms of voice, Kamien talk-sings, mumbles and occasionally plunges into a deep, warbly grandiose affectation.

The album opens with a mischievous ode to his wheelchair: “She is a plastic and chromium mistress / Black Naugahyde across the seat / Just a touch of padding in the right places / Oh when I ride her boys it feels so neat.” Though, later in the song he admits, “I hate to have to need her.”[14]

A 1985 review by Mike Joyce likens Kamien’s voice to “a little more tuneful” version of Lou Reed.[15] The comparison holds up: Kamien matches Reed’s sense of irony, though he avoids falling into the Velvet Underground frontman’s boredom and pessimism. Nearly every complaint that Kamien makes is followed by a qualification as if to say: things aren’t really that bad. His voice and musical style are also reminiscent of the Kinks, the Modern Lovers, the Violent Femmes and Pavement, though the album evades perfect comparisons. It is simply unique.

In the album’s climactic “I Got Nobody,” Kamien sardonically moans:

“Well, I’m just fine by myself / Just my shadow and me… / And my TV and my guitar now let’s see / that makes three… / Things I can depend on come hell or high-tide / If I ever loved a woman / Let’s just say that I lied.”[16]

While these lyrics might paint a bleak picture, Kamien found love not long after releasing his album. Interestingly, his activism in an organization meant to destigmatize disability played a large role in how he met his future wife.

In the late 80s, he became an advisory board member for a nonprofit called DateAble (pronounced with an emphasis on “able”), a dating service particularly designed for people “with disabilities or without them.”[17]

Prior to joining DateAble’s board, Kamien had been turned down from another dating service. He recalled, “I think I was the only one brazen enough to try … Their attitude was: ‘You should have known there was a problem. You should stay in your place.’”[18]

In a 1987 Washington Post article, Kamien explained:

“I personally want to try and change the stereotype of what somebody in a wheelchair is like… I want to be judged not on my disabilities but on my abilities. I think people get frightened by the wheelchair… It’s a powerful visual symbol, but it’s not a symbol of defeat. It’s a tool I use to help me accomplish my goals. Just by climbing into the wheelchair, I don’t have to surrender my sexuality, my sensuality, my good sense of humor, or anything.”[19]

While advocating for DateAble, he appeared on the Today show as a spokesperson. A woman named Mary Vicinus would see him on TV and determine: “I’m going to meet this man.”[20] And, indeed she did. Kit and Mary were married in 1988 at St. Elizabeth’s Catholic Church in Rockville, Maryland.[21]

Kit Kamien passed away due to complications of multiple sclerosis in 2007. He was 55 years old.[22] He lives on through the cherished memories of close friends and community members.

On Legacy.com, several friends posted memories in response to Kit’s obituary. One person, who received guitar lessons from Kamien in 1976 wrote: “Kit really did teach me more than guitar playing. Completely unselfconsciously, he taught confidence and accepting oneself. He taught courage. I saw that throughout the years I studied with him. He certainly showed how to approach life with joy and humor and find the best in one’s circumstances.”[23]

A high school friend, Michael Singer, described Kit as “inspiring and amazing and outrageous” in an email. In a phone call with Gantt Kushner of Gizmo Recording in Silver Spring, Gantt remembered sitting behind Kit in homeroom (their last names fell side-by-side alphabetically). When they discovered that they both played the guitar, Kit said: “You and I are going to be good friends.”

One of Kushner’s remarks particularly sparked the imagination. When asked about any good memories of Kit, Kushner coyly said: “I’ll have to think if I can come up with any publishable stories.” Some stories are best left untold.

As for Riki Schneyer, she described Kit as a brother to her “in every sense of the word, other than the biological.” I believe that Kit would have agreed. After all, his song—“Take Me For a Sister”—is dedicated “To Riki.”

Special thanks to Riki Schneyer, Gantt Kushner and Michael Singer for sharing their time and memories with me. They helped me to better understand their world, and their friend Kit.

Footnotes

- ^ Michael Mott, "Musician Not Singing Blues Over Handicap: Arts." The Washington Post (1974-Current File), Jul 16, 1981. https://search-proquest-com.dclibrary.idm.oclc.org/docview/147325964?accountid=46320.

- ^ “Definition of MS” and “MS Symptoms,” National Multiple Sclerosis Society. https://www.nationalmssociety.org/Symptoms-Diagnosis/MS-Symptoms.

- ^ Michael Mott, “Musician Not Singing Blues.”

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Richard Harrington, "Psyche Delly Gives Up the Beat: Higher Drinking Age, 'New Wave' Blamed for Nightclub's End Psyche Delly." The Washington Post, Jan 19, 1983. https://search-proquest-com.dclibrary.idm.oclc.org/docview/138057511?accountid=46320.

- ^ James Michael Causey, “When Bethesda Was Cool.” Bethesda Magazine, Jul, 25, 2016, https://bethesdamagazine.com/bethesda-magazine/july-august-2016/when-bethesda-was-cool/.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Richard Harrington, "Psyche Delly Gives Up the Beat.”

- ^ “Letters to the Editor,” Unicorn Times. June 1974. https://digdc.dclibrary.org/islandora/object/dcplislandora%3A30221?solr_nav%5Bid%5D=1a4e7bbf8cf81cf041ed&solr_nav%5Bpage%5D=0&solr_nav%5Boffset%5D=0#page/1/mode/1up.

- ^ Michael Mott, "Musician Not Singing Blues.”

- ^ Richard Harrington. "Kit Kamien." The Washington Post (1974-Current File), Jun 26, 1983. https://www.washingtonpost.com/archive/lifestyle/style/1983/06/26/kit-k….

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Kit Kamien, "Bitch on Wheels," Kit Kamien and the Back Room Players. Bias Recording, 1985.

- ^ Joyce, Mike. "Kit Kamien: Out of the Ordinary." The Washington Post (1974-Current File), Oct 25, 1985. https://search-proquest-com.dclibrary.idm.oclc.org/docview/138444604?accountid=46320.

- ^ Kit Kamien, "I Got Nobody," Kit Kamien and the Back Room Players. Bias Recording, 1985.

- ^ Claudia Levy, "Dating Service for Disabled is Designed to Overcome Social Handicaps: Some Advocates for Disabled Question Wisdom of Separate Dating Service." The Washington Post (1974-Current File), Oct 13, 1987. https://search-proquest-com.dclibrary.idm.oclc.org/docview/139307008?accountid=46320.

- ^ Barbara Gamarekian, "DATING SERVICE HELPS PHYSICALLY DISABLED: [SUN-SENTINEL EDITION]." Sun Sentinel, Oct 14, 1987. https://search-proquest-com.dclibrary.idm.oclc.org/newspapers/dating-service-helps-physically-disabled/docview/389511352/se-2?accountid=46320.

- ^ Claudia Levy, "Dating Service for Disabled is Designed to Overcome Social Handicaps.”

- ^ “Mary V. Kamien,” Omps Funeral Home and Cremation Center, Jan 22, 2019. https://ompsfuneralhome.com/obituary/mary-v-kamien/.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ “Kit Christopher Kamien,” Legacy.com. Feb 18, 2007. https://www.legacy.com/obituaries/name/kit-kamien-obituary?pid=86632999.

- ^ Ibid.

![Sketch of the mythical fuan by Pearson Scott Foresman. [Source: Wikipedia]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2023-10/Goatman_Wikipedia_Faun_2_%28PSF%29.png?h=64a074ff&itok=C9Qh-PE1)