James Nabrit Jr. and His Uncompromising Assault on Segregation

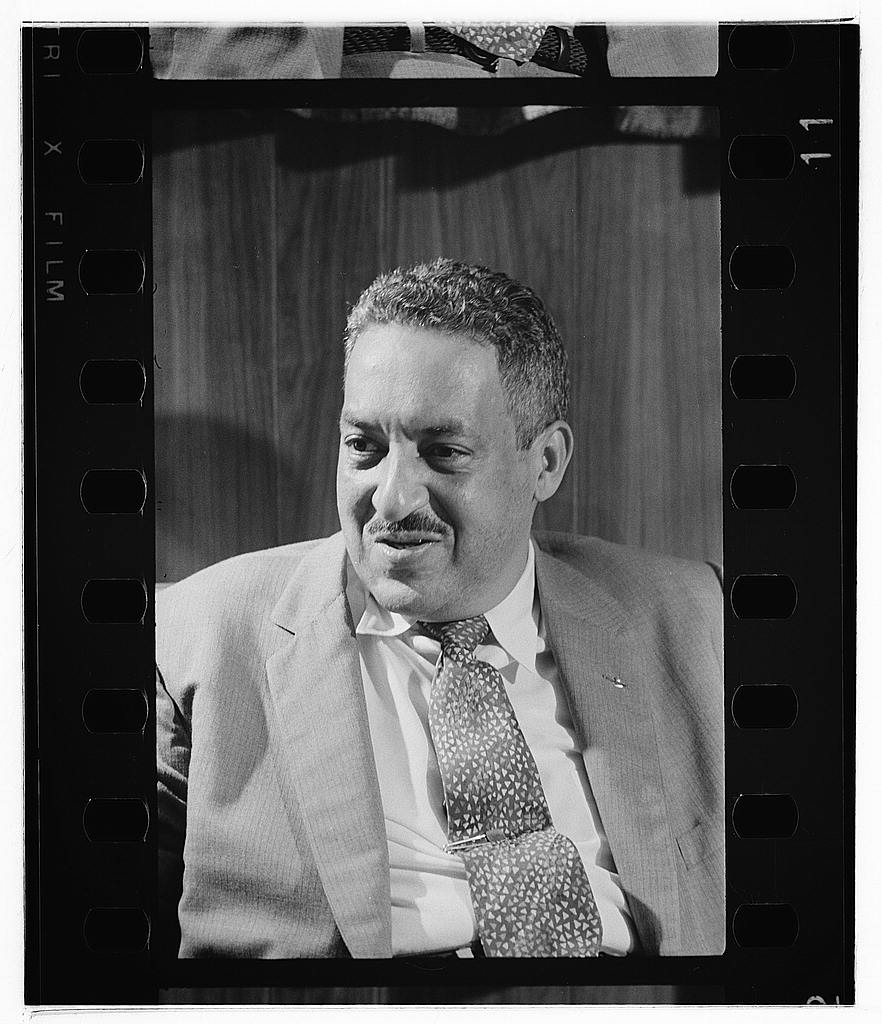

James Madison Nabrit Jr, the son of a Georgia minister, who had witnessed horrific racial violence growing up in the Jim Crow South, joined the faculty of the Howard University Law School at the urging of Charles Hamilton Houston. In his new role on Houston’s team of elite Black legal scholars, the young professor developed and taught the first full course on civil rights law ever offered by an American law school.[1]

Nabrit later picked up the mantle of the District’s school desegregation fight after Houston died in 1950, and he significantly influenced the direction of the national, NAACP-led struggle for school desegregation. He went on to lead the Howard University School of Law and become the university’s president years later.

Professor Nabrit--referred to as “Jim Reds” by some of his students likely because of his reddish hair--dedicated most of his civil rights law curriculum to dissecting and eviscerating the legal arguments of Plessy v. Ferguson, which established the doctrine of “separate but equal.” One of his pupils, Dovey Johnson Roundtree, who matriculated into Howard in 1947, reflected on Nabrit’s class in her memoir:

Line by line, layer by layer, Dr. Nabrit ripped away the veneer of judicial authority that encased the Plessy decision, unmasking for us a truth that remained hidden from our privileged white counterparts at other law schools, where, in the 1940s, Plessy was carefully ignored...Nabrit alone among American law professors had dared to take it on.[2]

Nabrit believed the doctrine outlined in the 1896 case was so flawed that it rose to the level of being “un-Christian” and “un-American.”[2] The Court, he argued, would always fall back on the Plessy doctrine if given the opportunity, forever denying Black Americans true equality. Thus, civil rights lawyers should avoid citing the doctrine when arguing before the Court.

It was this uncompromising belief in the illegitimacy of the Plessy doctrine that led Nabrit to push back on Houston and Thurgood Marshall’s legal strategy of equalization. “We had nothing to lose by an outright assault on segregation,” Nabrit said of the “serious difference of opinion” between him and Thurgood Marshall.[3]

“To invoke Plessy even as a fallback position was in Nabrit’s view to be complicit in the evil, to give credence to the lie, to feed its poison,” Roundtree recalled of her professor’s beliefs, “Though he never raised his voice, Professor Nabrit seemed to thunder as took on the NAACP’s tempered approach.”[2]

Nabrit believed that Marshall personally agreed with him but was concerned with delivering results. “After all, the NAACP got its funds from many people who wanted these cases won, even if on the wrong grounds. Thurgood understood my argument...but he had a constituency out there,” Nabrit argued.[3]

When Gardner Bishop approached the Howard professor in the Spring of 1950 about continuing Houston’s work as counsel, Nabrit agreed with one caveat: they must abandon Houston’s equalization cases and form a new case that attacks segregation head on.

The Most Devastating Forces at Hand

In his first brief for the new case, Bolling v. Sharpe, Nabrit never once mentioned the unequal conditions of Black schools in the District. He laid his entire case upon the inherent injustice of segregation. Instead of trying to prove that the District schools were unequal, he put the burden of proof upon the District officials to find a justifiable reason for why separate systems should exist at all.[1]

Aside from the difference in strategy between Bolling’s desegregation argument and the NAACP’s equalization tact, Nabrit’s case was also unique because it couldn’t rely on the principle of “equal protection of the law” as outlined in the Fourteenth Amendment.

The amendment says, in part, that “No State shall make or enforce any law which shall abridge the privileges or immunities of citizens of the United States.” This landmark civil rights amendment, whether on purpose or through tragic oversight, excluded the citizens, chiefly the Black citizens, of the District of Columbia from equal protection under the law.

Nabrit, instead, relied on the affirmation of the right to liberty written in the fifth amendment, which applies to all citizens regardless of whether they live within a set of borders called a state, as opposed to just a district or territory: No person shall be...deprived of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law.

He cited the Japanese internment cases of WWII, in which the Court set a high bar of threat to national security for temporary deprivations of liberty. Nabrit argued that under this precedent the District school board was treating Black children as criminals, arbitrarily depriving them of liberty.[1]

In April 1951, District Court Judge Walter Bastian ruled against Nabrit’s argument, citing that no claim of unequal conditions had been made and therefore no relief could be provided. This defeat in District Court bolstered Thurgood Marshall’s belief that a more measured approach in the courts was necessary to make incremental progress.[1]

Over the next year, Marshall continued to hedge his argument, and he and his team of NAACP lawyers argued for equalization in school segregation cases in Virginia, Delaware, South Carolina, and Kansas. The latter most of which formed the name that would go down in this chapter of American history books: Brown v. Board of Education.

Nabrit, unmovable in his belief of the immorality of Plessy, persisted with his full frontal approach and pressured Marshall to change tact. At an April 1952 conference at Howard, with 300 of the nation’s leading Black scholars and lawyers in attendance, Nabrit was the most outspoken attendee on the need for aggressive action.

Other presenters urged Marshall and the NAACP team to be even more cautious in their approach. John Frank, an advisor to Marshall, compared an all-out attack on segregation to an army abandoning its most important line of defense, “The most daring army guards its lines of retreat. So should a litigation strategist.” Another lawyer suggested that even a national strategy of litigation was too broad and that the NAACP should secure victories in the border areas, instead of the Deep South.[1]

Nabrit railed against these cautious approaches, speaking in unequivocally bold terms:

The attack should be waged with the most devastating forces at hand. Let the Supreme Court take the blame if it dares to say to the entire word, ‘Yes, democracy rests on a legalized caste system. Segregation of the races is legal.’ Let the Court write this across the face of the Constitution: ‘All men are equal, but white men are more equal than others.’[4]

Nabrit’s impassioned speech at the conference pushed Marshall towards a more robust attack on segregation, and, the next month, when he filed a statement of jurisdiction at the Supreme Court for the South Carolina case, Marshall wrote in direct language similar to that which Nabrit had endorsed all along.[1]

“On occasion, the courts have denied that enforced segregation of Negroes in American life is a badge of inferiority, thus closing their eyes as judges to what they must know as men,” the statement read.[1]

As the District group was working on appealing the District Court decision in October 1952, Nabrit received a phone call from a clerk at the Supreme Court. Chief Justice Fred Vinson had asked for the Bolling case to be heard directly by the Supreme Court alongside the NAACP’s cases, bypassing the Court of Appeals.[5]

The Basic Question Here is One of Liberty

In December 1952, Nabrit appeared before the U.S. Supreme Court, with his co-counsel George E.C. Hayes. Hayes was a longtime colleague of Nabrit, joining the Howard law school faculty even before Houston became vice dean.

During Nabrit’s portion of the argument, he once again harkened back to the Japanese-American internment cases:

We ask nothing different than that we be given the same type of protection in peace that these Japanese were given in time of war...We are simply saying that liberty to us is just as precious, and that the same way in which the Court measures out liberty to others, it measures to us.[6]

In his closing argument, as the climax of the legal battle for school integration in the nation’s capital, Nabrit employed the full weight of the definition of liberty itself to support his case:

The basic question here is one of liberty, and under liberty, under the due process clause, you cannot deal with it as you deal with equal protection of laws, because there you deal with it as a quantum of treatment, substantially equal. You either have liberty or you do not...We submit that in this case, in the heart of the nation’s capital, in the capital of democracy, in the capital of the free world, there is no place for a segregated school system. This country cannot afford it, and the Constitution does not permit it, and the statutes of Congress do not authorize it.[7]

After Chief Justice Vinson died unexpectedly of a heart attack in 1953, the new Chief Justice, Earl Warren, asked to rehear the cases, and finally, on May 17, 1954, the Supreme Court was ready to hand down a decision on the five school segregation cases.

Nabrit invited Roundtree, his pupil who had watched him craft his argument against Plessy and bring his District case to court, to hear the verdict in the Supreme Court chamber on the day of the verdict. Roundtree recalled in her memoir:

There are times when the world, after interminable waiting, changes in a single moment. Monday, May 17, 1954, was one of those times...All the agony that followed in the wake of that historic ruling, including the agony of our present-day struggle to fulfill its promise, has not diminished what the Court did that day.[4]

In his unanimous majority opinion for the Bolling case, Chief Justice Warren agreed with Nabrit that the District had unjustly deprived the children of liberty and due process:

Although the Court has not assumed to define 'liberty' with any great precision, that term is not confined to mere freedom from bodily restraint. Liberty under law extends to the full range of conduct which the individual is free to pursue...Segregation in public education is not reasonably related to any proper governmental objective, and thus it imposes on Negro children of the District of Columbia a burden that constitutes an arbitrary deprivation of their liberty.[8]

Footnotes

- a, b, c, d, e, f, g Kluger, Richard. "The Best Place to Attack" in Simple Justice: The History of Brown v. Board of Education and Black America’s Struggle for Equality. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2004.

- a, b, c McCabe, Katie and Roundtree, Dovey Johnson. "The Assault on Plessy v. Ferguson" in Justice Older Than The Law: The Life of Dovey Johnson Roundtree. Jackson: University of Mississippi Press, 2009.

- a, b Kluger, Richard. "On the Natural Inferiority of Bootblacks" in Simple Justice: The History of Brown v. Board of Education and Black America’s Struggle for Equality. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2004.

- a, b McCabe, Katie and Roundtree, Dovey Johnson. "Taking on the 'Supreme Court of the Confederacy'" in Justice Older Than The Law: The Life of Dovey Johnson Roundtree. Jackson: University of Mississippi Press, 2009.

- ^ McNeil, Genna Rae. "Community Initiative in the Desegregation of District of Columbia Schools, 1947-1954: A Brief Historical Overview of Consolidated Parent Group, Inc. Activities from Bishop to Bolling," Howard Law Journal 23, no. 1 (1980): 25-42

- ^ Nabrit, James. Bolling v. Sharpe, Oral Arguments. University of Michigan. https://apps.lib.umich.edu/brown-versus-board-education/oral/Hayes&Nabr…

- ^ Nabrit, James. Bolling v. Sharpe, Oral Arguments. University of Michigan. https://apps.lib.umich.edu/brown-versus-board-education/oral/Nabrit&Kor…

- ^ Bolling et. al. v. Sharpe et. al. 347 U.S. 497 [1954]

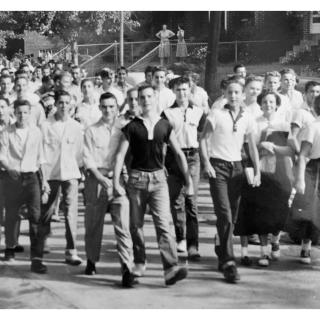

![This integrated classroom at Anacostia High School is the culmination of a seven year struggle against DC's segregated school system. [Source: LOC] Integrated classroom at Anacostia High School](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/AHS%20Class_0.jpg?itok=GNxSJFox)

![Sketch of the mythical fuan by Pearson Scott Foresman. [Source: Wikipedia]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2023-10/Goatman_Wikipedia_Faun_2_%28PSF%29.png?h=64a074ff&itok=C9Qh-PE1)