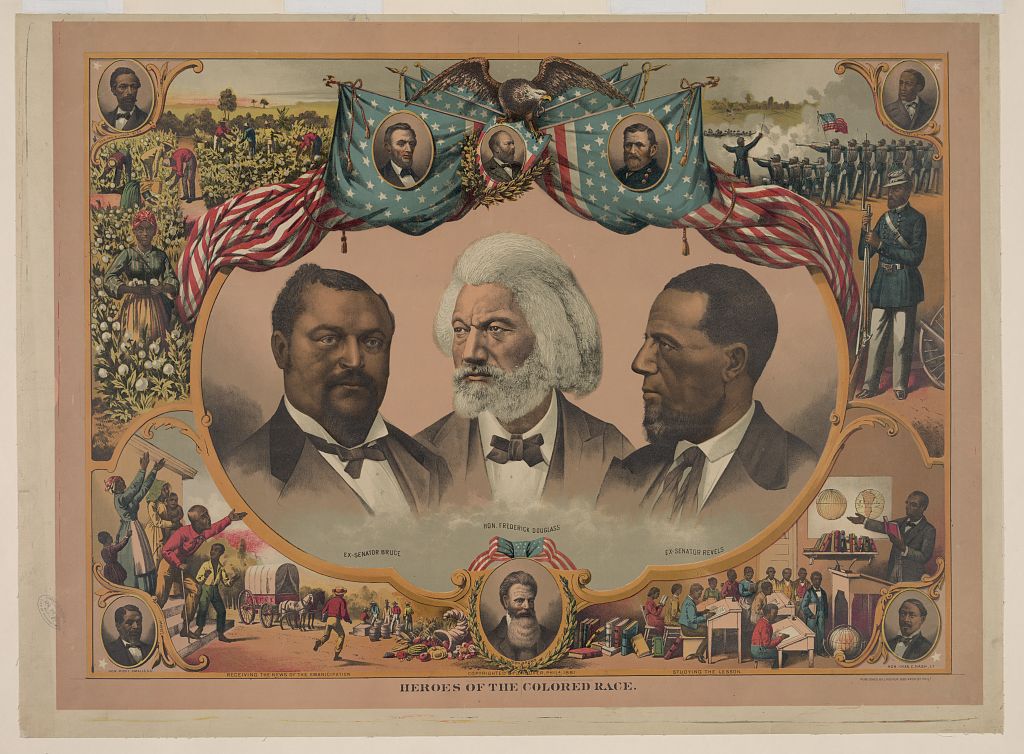

Blanche Bruce's Washington: The First Black Senator Took His Seat in 1875

In February 1875, Blanche Bruce arrived in Washington to assume his seat in the Senate. Months earlier, the Mississipian had become the first Black man to ever win a full term in the upper house of Congress, a feat unequaled for another 90 years. He had risen from slavery to the pinnacle of American politics in barely a decade, accumulating friends, wealth, and fame along the way. But when Bruce arrived in the nation’s capital, few seemed to notice.

For many, the coming of the polished and portly senator-elect seemed like an aberration. As Bruce completed his rise to power, the fragile foundations of America’s post-Civil War democracy were crumbling. All over the South, white supremacists drove Black men from office at gunpoint. Hundreds were killed in Bruce’s native Mississippi.[1] Amid the chaos of the next few years, one thing became increasingly clear to the young senator: there would be no going back to the Magnolia State. Instead, Blanche Bruce would tether his career and legacy to the District of Columbia.

Though only 34 when he took office, Bruce was no stranger to moving. He was born in central Virginia in 1841, the son of an enslaved woman and (most likely) her White master. As a child, Bruce was moved across the Upper South, eventually landing in Missouri. When the Civil War broke out, the young man escaped across the border to Kansas. He soon left to study at Oberlin College in Ohio, then returned to Missouri to open a school for Black children.[2]

But with the Civil War over and the federal government protecting newly-freed African Americans, Bruce made his most consequential move. He sailed to the Mississippi Delta with 75 cents in his pocket, and swiftly became one of the most important men in the state. With a talent for political organizing and the elegant “manners of a Chesterfield,” he easily found a place in Mississippi’s new multi-racial democracy. He became sergeant-at-arms of the state legislature, then sheriff, tax collector, and political boss of Bolivar County. Bruce leveraged his salary to buy a cotton plantation, worked by Black sharecroppers.[3] Though the perks of office and wealth enticed him, he also had a vision for post-slavery America. All Black people needed, Bruce wrote, is “what is freely accorded to the white man,” the protections of law and a fair chance at education and wealth.[4]

In 1874 Bruce capped his meteoric rise by winning a Senate seat. Even anti-Black newspapers in Vicksburg praised his skill and intelligence.[5] However, the world Bruce encountered in Washington was a far cry from Mississippi. With few connections in D.C, he was thrust into a Senate that had little interest in supporting its only Black member. When Bruce came to take the oath of office, his colleague from Mississippi refused to even set down his newspaper to accompany Bruce to the podium, as was customary. Though he was rarely slighted that publicly, Bruce still felt isolated. He was unable to counter the new federal indifference to violence against Black southerners, and his notions of uplifting people of color became a rear-guard struggle to protect what they already had. As his biographer Lawrence Otis Graham wrote, Bruce was “intimidated and overwhelmed by the hostile mood” he faced.

But as his term progressed, Bruce found a footing. He left substance for style, letting his impeccable manners and intelligence speak for themselves. He emphasized to White senators that, as far as he was concerned, the horrors of slavery could be treated as forgotten and forgiven. When Bruce encountered Sen. Lewis Bogy of Missouri, who had tried to cheat him out of a quarter when Bruce was an enslaved tenant, he purposefully helped Bogy pass a bill, “just to demonstrate that strange things frequently happen in the world and that I bore him no malice.” Soon, even former Confederates in Congress spoke well of Bruce, at the same time they pushed people like him out of American democracy.[6]

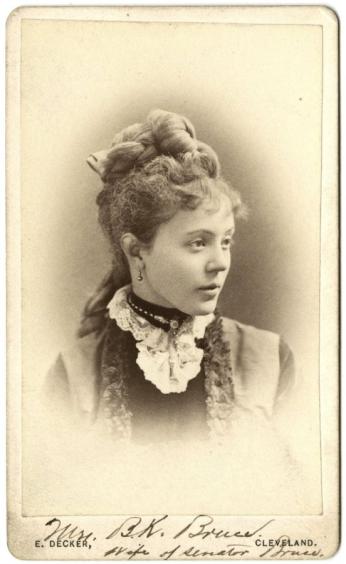

As he became a well-respected man in Washington, Bruce decided to start a family in the District, away from the violence that might await him in Mississippi. He married Josephine Wilson, who came from one of Cleveland’s wealthiest Black families. The match was not without controversy. Bruce may have been the most powerful African American in the nation, but Josephine’s free-born parents worried that he was too “negroid-looking” and stained by slavery to be a suitable match. When the two wed in 1878, Bruce’s family was not invited. In fact, he did not even tell them he was getting married. After the nuptials, the couple embarked on a European honeymoon that wowed papers across the continent.[7]

When they returned, Bruce used money generated by his plantation in Mississippi to buy a luxurious home at 909 M Street NW. It became a hub of Washington high society. Aided by a cadre of servants, the Bruces threw lavish parties for the city’s best, dining with politicians, businessmen, and local icons like Clara Barton. Described by one guest as a “great big good natured lump of fat,” Bruce excelled in social circles, especially when accompanied by his undeniably beautiful wife.[8]

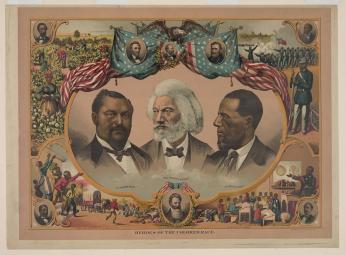

But within the Bruce house, other Black faces were often hard to come by. Josephine possessed a “noted antipathy toward poor people,” which extended even to the city's Black middle class. This perspective was hardly uncommon in Washington. The city was home to most of Black America’s leading figures, including Bruce, Frederick Douglass, and wealthy families like the Wormleys and Terrells. But this elite circle distanced themselves from ordinary Black Americans. Most were well-off, well-educated, and very light-skinned, and they saw little in common with darker and poorer Black people.[9]

Bruce was no exception, but he made his separation less obvious. In fact, the Washington Bee, the city’s Black newspaper, praised him for acting “less like a white man” than other leaders like John Mercer Langston or even Frederick Douglass, who infuriated many by marrying his young white secretary. According to the Bee, Douglass and others were “colored white men,” while Bruce was just “a really whitened African.”[10]

But the ties between Bruce and Washington’s wider Black community strained as he transitioned from the Senate. With no hope of reelection, Bruce grew somewhat bolder, denouncing racism against Black people, Native Americans, and Chinese immigrants. Even still, Bruce kept an “almost single-minded obsession for maintaining favor with powerful Whites.”[11] In part, this obsession reflected his faith in assimilation as the path to Black equality. But it also advanced his self-interest. Bruce wanted to preserve his political career, so he needed powerful White friends.

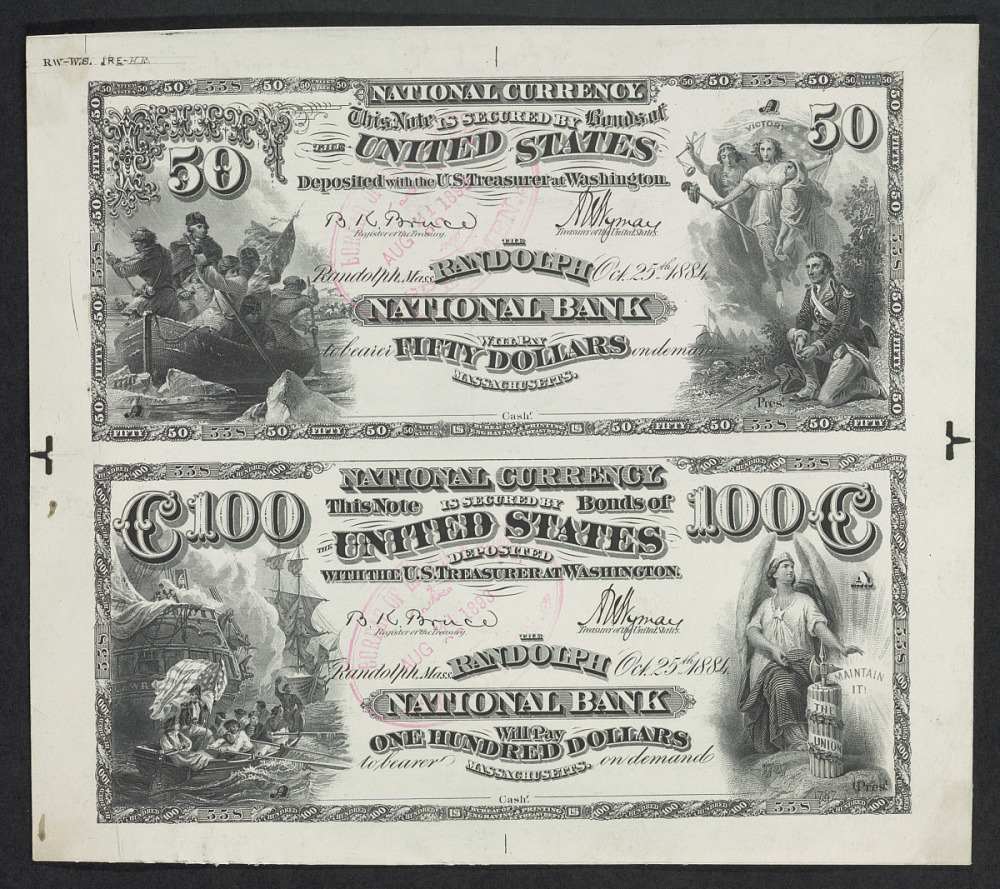

When his Senate term expired, Bruce used the goodwill he built to become register of the Treasury, a powerful office overseeing federal debt. As a perk, his name would appear on U.S. currency. Bruce embraced the job and worked with characteristic diligence. But to the chagrin of some Black commentators, Bruce did nothing to boost racial diversity among his staff. Their anger at him only deepened after Grover Cleveland became president in 1885. As a Democrat, Cleveland seemed likely to fire Black Republicans like Bruce. In an attempt to keep his job, Bruce came out in support of Cleveland and said that all “charges of violence and intimidation at the polls” against Black voters “are altogether false.” Black allies were incensed, and Cleveland sacked him anyway. However, when Republicans regained the White House four years later, Bruce became Washington’s Recorder of Deeds, a small but high-paying office.

When Frederick Douglass died in 1895, Bruce became the undisputed dean of the Black Washington elite. He and Josephine lived in a mansion near Dupont Circle, which Bruce kept well-furnished through plantation income and a broad investment portfolio. His wealth hovered somewhere around $150,000 (over $4 million in 2021 dollars). He sent his son to Phillips Exeter Academy, in preparation for Harvard.[12]

But elsewhere, Bruce and the community he led struggled. The White families who had attended his parties now rejected invitations, as the social equality that had emerged among wealthy Washingtonians vanished once Jim Crow segregation set in. He and other Black aristocrats “withdrew into a world of their own.”[13] Things were no better politically. With most African Americans disenfranchised, Bruce’s ability to organize their votes was no longer useful. By aggressively campaigning for William McKinley, Bruce managed to regain his office as register of the Treasury in 1897, but what he truly coveted, a cabinet post, became an impossible dream. Months later, he was stricken with a kidney ailment, which took his life in March 1898.[14]

Bruce’s death sparked tributes from every corner of Washington. His funeral was attended by congressmen, businessmen, and community leaders, with luminaries like President McKinley sending wreaths. The Washington Bee praised him as “a man who was true to every trust,” while the White-run Evening Star said that he was “known in all portions of the country as able, brainy, and upright.”[15]

But perhaps the most fitting obituary came from the Washington Post, then a conservative publication opposed to civil rights. The Post called him “one of the apostles of kindness,” a man whose manners surpassed the “noisy impudence and absurd pretensions” of more assertive Black leaders. His lack of bitterness demonstrated the “deep and generous affection” that former slaves hold for their southern masters. Most importantly, they wrote (with praise) that in his long career Bruce had never tried to elevate “his race to a position to which ninety-nine hundredths of them were hopelessly ineligible.” In their view, he behaved just as a Black man should in a White man’s country.[16]

It was a telling and ironic coda to the life of Blanche Bruce, who rose so high but could never seem to bring anyone else along with him.

Footnotes

- ^ Lawrence Otis Graham, The Senator and the Socialite: The True Story of America's First Black Dynasty, (New York: HarperCollins, 2006), 64-69.

- ^ Ibid, 9-24, 32-44.

- ^ Ibid,44-62. Howard N. Rabinowitz, Southern Black Leaders of the Reconstruction Era, (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1982), 4-12 (quote on 6). Willard Gatewood, Aristocrats of Color: the Black Elite, 1880-1920, (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1990), 36. Eric Foner, Freedom’s Lawmakers: Directory of Black Officeholders During Reconstruction, (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1996), 29.

- ^ Rabinowitz, Southern Black Leaders, 22. Quote from “Ex-Senator Bruce’s Letter,” Washington Post, June 13, 1889, 4.

- ^ Graham, The Senator, 64.

- ^ Ibid, 69-86. Gatewood, Aristocrats, 12-26. “Senators Bruce and Bogy: How the Black Man Reminded the White of a Former Interview,” Washington Post, October 24, 1886, 6.

- ^ Graham, The Senator, 87-99.

- ^ Ibid, 100-102. Rabinowitz, Southern Black Leaders, 27. “Color in Congress,” Evening Star, October 28, 1893, 17. Gatewood, Aristocrats, 4.

- ^ Graham, The Senator, 102-104, 120, 143-144. Gatewood, Aristocrats, 9.

- ^ “A Most Popular Leader,” Washington Bee, Sept 12, 1891, 1.

- ^ Graham, The Senator, 123-124, 130.

- ^ Ibid 147, 159, 168, 173. Gatewood, Aristocrats, 44.

- ^ Gatewood, Aristocrats, 37.

- ^ Graham, The Senator, 188-192.

- ^ “Last of the Home Guard: Hon Blanche K. Bruce is Dead!,” Washington Bee, March 19, 1898, 4. “Register Bruce Dead,” Evening Star, March 17, 1898, 1.

- ^ “Last of the Home Guard: Hon Blanche K. Bruce is Dead!,” Washington Bee, March 19, 1898, 4. “Register Bruce Dead,” Evening Star, March 17, 1898, 1.

![Sketch of the mythical fuan by Pearson Scott Foresman. [Source: Wikipedia]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2023-10/Goatman_Wikipedia_Faun_2_%28PSF%29.png?h=64a074ff&itok=C9Qh-PE1)