We'wha Visits the Capital

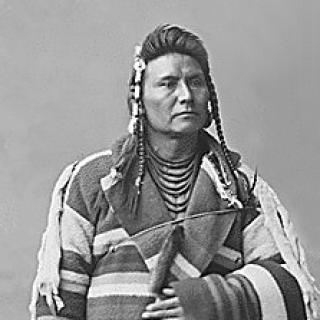

Before 1885, We’wha had never seen a city, and the city of Washington, D.C. had never seen a person quite like We’wha. Alongside being a pottery maker and cultural ambassador, We’wha was a lhamana, who in the Zuni tradition are male-bodied people who also possess female attributes. Existing outside of the Western gender binary, lhamana have always inhabited a special role in Zuni society, as intermediaries between men and women, who perform special cultural and spiritual duties.[1] More recent scholarship coined the term Two Spirit "as a means of unifying various gender identities and expressions of Native American / First Nations / Indigenous individuals."[2]

We’wha arrived in Washington in December of 1885 with Matilda Coxe Stevenson and James Stevenson, a husband-and-wife team of anthropologists who had been doing research for the newly-formed Bureau of Ethnology. The Stevensons met and befriended We’wha in Zuni, which is ancestral territory located in the Southwest of North America. At this point, the Zuni tribe had little contact with Western colonists, and no Zuni people spoke English.[3] Nonetheless, Matilda and We’wha forged an enduring friendship, and the anthropologist immediately identified We’wha as someone remarkable.

Stevenson wrote of We’wha:

“She was perhaps the tallest person in Zuni; certainly the strongest, both mentally and physically ... She had a good memory, not only for the lore of her people, but for all that she heard of the outside world ... She possessed an indomitable will and an insatiable thirst for knowledge. Her likes and dislikes were intense. She would risk anything to serve those she loved, but toward those who crossed her path she was vindictive. Though severe she was considered just.”[4]

When it comes to pronouns, the contemporary and historic literature about We’wha are not consistent: both “he” and “she” have been used almost equally. All 19th century newspaper accounts painted a feminine picture of We’wha, using pronouns “she” and “her,” and describing We’wha with terms like “princess,” “priestess,” “maiden,” “intelligent young woman,” and “debutante.” Seemingly, everybody assumed that We’wha was a woman.

By contrast, the historian Will Roscoe—who wrote a 1991 biography of We’wha—justified his use of male pronouns through his research of the Zuni tribe. He wrote: “The Zunis referred to lhamanas by saying ‘She is a man.’”[5] For the sake of this article, I am choosing to use the pronouns “they” and “them” to describe We’wha, to remain faithful to the nonbinary nature of the lhamana.

Between December and June, We’wha was immersed in Washington society. They were a fast student of the English language, and provided invaluable information for the Stevensons to identify and document Zuni artifacts.[6] In May of 1886, they met a reporter from The National Tribune, who described their encounter: “The writer hereof was introduced to her there at one of Mrs. Stevenson’s Friday afternoon receptions, when others also were calling, yet, on repeating the visit three or four weeks later, Wewha, who was alone in the parlor at the time, at once recognized the voice and stepped to the door, saying, as she held out her hand to shake hands, ‘How do you do? Walk in. Sit down.’ All was said in a cordial tone and with a very bright smile.”[7]

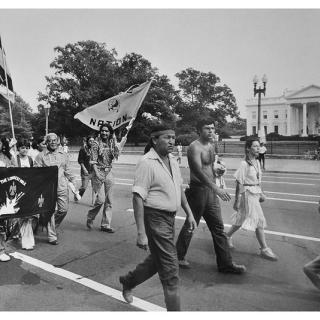

We’wha participated in a number of high society events from “teas with fashionable ladies,”[8] to a ball called “The Kirmes” held at the New National Theater.[9] On June 24, We’wha even had an audience with President Grover Cleveland. The Washington Post remarked: “We Wah, the Zuni princess, walked up the broad entrance to the White House yesterday, and, in company with Mrs. Col. Stevenson, was shown into the Green Room. She was dressed in her aboriginal costume, and wore a headdress of feathers. Her conversation with the President was mainly in monosylables [sic], but Mrs. Stevenson and the President had quite an interesting talk.”[10]

While researching a figure like We’wha, it is hard to ignore the ways that they were misunderstood and exoticized by contemporary Washington society. Newspapers took a particular interest in their appearance. At the Kirmes, one reporter wrote: “We Wah, the Zuni priestess, who took part in this dance, wore a gorgeous blanket of white, embroidered in the royal fashion. Her tawny black locks were tied with green ribbon. She betrayed some surprise at the curious movement of the dance, and said she had not seen anything just like it among her people, but it was very nice notwithstanding.”[11]

Some of the history is uncomfortable, especially as pertains to the prevailing attitude toward Native American people and customs. As referenced in the last quote, one of the dances at the Kirmes was a so-called “Indian dance,” which was a performance made by white people in “genuine Apache style.”[12] Of course, rather than being “genuine,” this performance was appropriative, and operated on racist generalizations of Indigenous Americans for the enjoyment of a white audience. The Washington Post described the dance: “There was the civilized version of the war cry, the circling about a captive group, there was brandishing of tomahawks and waving of feathers, and in the midst there was a real Zuni priestess to give the thing local coloring.”[13]

Accounts like this give the sense that many Washingtonians were only interested in engaging with a fictionalized version of Indigenous culture. Despite the ways that Washington society accepted and praised We’wha, there remains a certain feeling of exploitation. In the portrait of We’wha written in The National Tribune, the author describes how We’wha became involved with the dance at the Kirmes:

“From the first Wewha took the greatest interest in [the Indian dance], and attended several of the rehersals [sic] as a spectator and made some valuable suggestions. Finally she was persuaded to appear in it herself, but it required much coaxing before she gave her consent, for as a priestess in Zuni dancing is to her a religious rite, and she had conscientious scruples about being in a dance given for the amusement of spectators. So she spent three hours praying aloud to seek guidance of her gods on the day before the Kirmes, and finally consented to take part in the Indian dance. She painted a ‘prayer stick’ and carried it with her to the theater, and waved it while in the dance, keeping perfect time to the dance.”[14]

Though this chain of events does not convey a high level of cultural sensitivity on the part of We'wha's hosts, it is interesting to see the ways that We'wha asserted their agency and made their voice heard. While we cannot hear these stories from We'wha's point of view, I find that their personality shines through the accounts written about them. By contributing to and participating in a less-than-genuine “Indian dance,” We’wha lended some authenticity to the performance, not just to “give the thing local coloring,” but by having dialogue and cultural exchange with their white peers. Despite misunderstandings, intolerances and complex dynamics, We’wha brought an authentic piece of Zuni to Washington.

Click here to learn about the Zuni A:shiwi A:wan Museum and Heritage Center.

Footnotes

- ^ A note on the Zuni attitude toward gender from historian Will Roscoe: “In their world view, the social roles of men and women were not biologically determined but acquired through life experience and shaped through a series of initiations. The Zunis referred to this socialization process metaphorically. Individuals were born ‘raw.’ To become useful adults they had to be ‘cooked.’ For the Zunis, gender was a part of being ‘cooked’—a social construction ... They viewed lhamanas as occupying a third gender status, one that combined both men’s and women’s traits—an unusual but possible configuration given Zuni beliefs about the construction of gender identity.” Roscoe, Will. "We'wha and Klah the American Indian Berdache as Artist and Priest." American Indian Quarterly 12, no. 2 (1988): 127-50. Accessed June 22, 2021. doi:10.2307/1184319.

- ^ Tony Enos, "8 Things You Should Know About Two Spirit People." Indian Country Today, Sep 13, 2018. https://indiancountrytoday.com/archive/8-misconceptions-things-know-two….

- ^ Nancy P. McKee and Linda Stone. “Readings in gender and culture in America.” Prentice Hall, Pearson Education Inc, 2002. https://archive.org/details/readingsingender0000unse/page/218/mode/2up? q=lhamana.

- ^ McKee and Stone. “Readings in gender.”

- ^ Will Roscoe. "We'wha and Klah the American Indian Berdache as Artist and Priest." American Indian Quarterly 12, no. 2 (1988): 127-50. Accessed June 22, 2021. doi:10.2307/1184319.

- ^ The National tribune. [volume] (Washington, D.C.), 20 May 1886. Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress. <https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/ sn82016187/1886-05-20/ed-1/seq-2/>

- ^ The National tribune. 20 May 1886. Chronicling America.

- ^ The National tribune. 20 May 1886. Chronicling America.

- ^ "DANCING IN GAY DRESSES: THE KIRMES PROVES A MOST SUCCESSFUL AFFAIR. A SUCCESSION OF BEAUTIFUL PICTURES AFFORDED DURING THE EVENING-THE PRESIDENT IN ATTENDANCE-THE DANCERS AND THEIR CHARMING COSTUMES-SOME OF THE PERSONS WHO WERE PRESENT." The Washington Post (1877-1922), May 14, 1886. https:// www-proquest-com.dclibrary.idm.oclc.org/historical-newspapers/dancing-gay-dresses/docview/ 138040956/se-2?accountid=46320.

- ^ "THE NEWS OF THE CAPITAL: A DEMOCRATIC CAUCUS TO-NIGHT." 1886. The Washington Post (1877-1922), Jun 24, 1. https://www-proquest-com.dclibrary.idm.oclc.org/historical-newspapers/ news-capital/docview/138040200/se-2?accountid=46320.

- ^ THE DANCES.: THE NAMES OF THE PARTICIPANTS, AND THEIR COSTUMES GIVEN. THE TYROLEAN DANCE. IN THE SWEDISH DANCE. IN THE JAPANESE DANCE. IN THE INDIAN DANCE. IN THE FLOWER DANCE. IN THE GYPSY DANCE. (1886, May 14). The Washington Post (1877-1922) Retrieved from https://www-proquest-com.dclibrary.idm.oclc.org/historical-newspapers/ dances/docview/138041013/se-2?accountid=46320.

- ^ "DANCING IN GAY DRESSES" The Washington Post.

- ^ "DANCING IN GAY DRESSES" The Washington Post.

- ^ The National tribune. 20 May 1886. Chronicling America.

![Sketch of the mythical fuan by Pearson Scott Foresman. [Source: Wikipedia]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2023-10/Goatman_Wikipedia_Faun_2_%28PSF%29.png?h=64a074ff&itok=C9Qh-PE1)