Man Missing: Scarlet Crow's Fateful Visit to Washington, D.C.

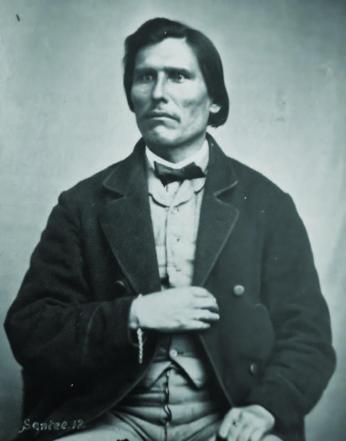

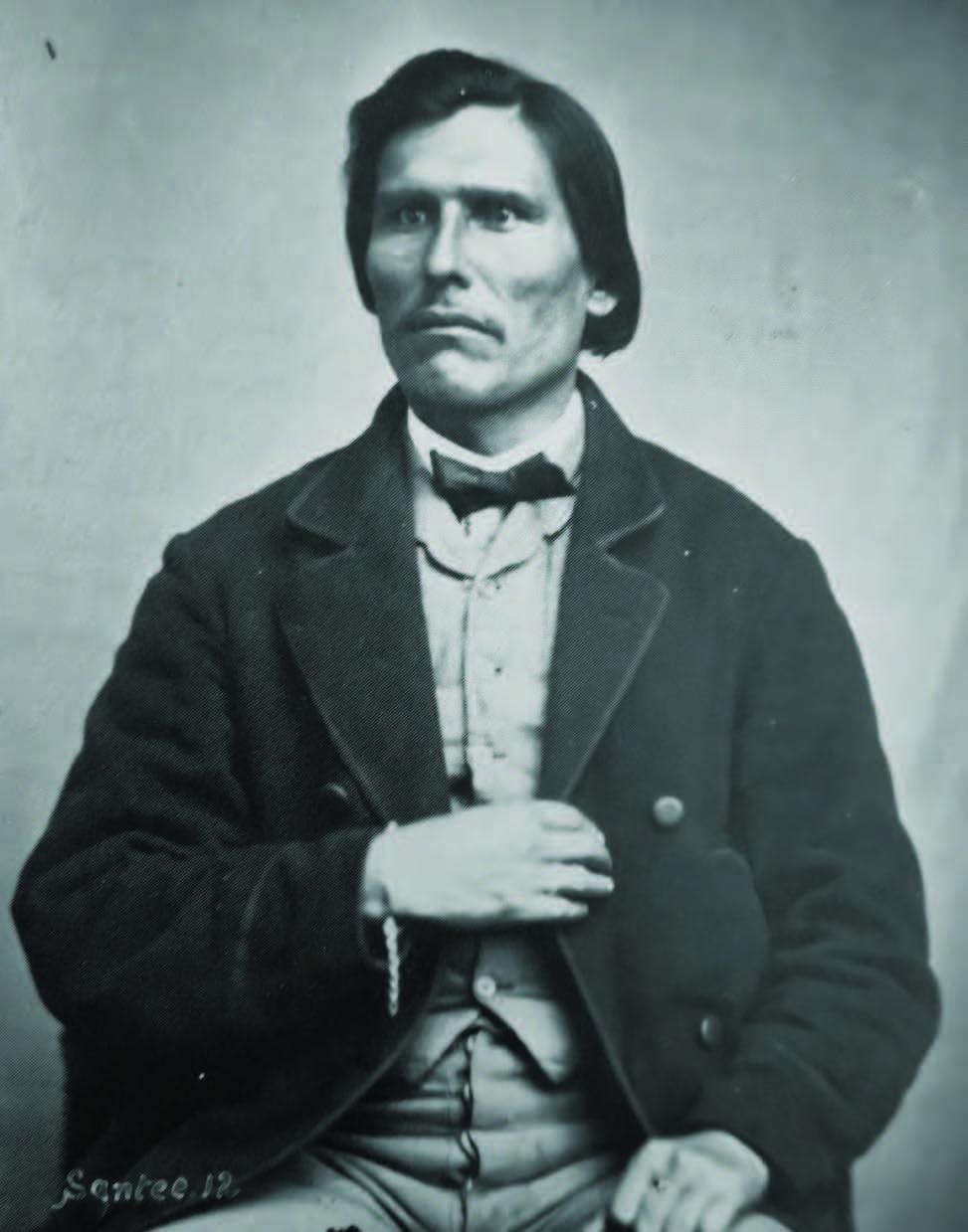

On the night of February 24, 1867 in the nation’s capital, a visiting Sioux chief mysteriously disappeared. Scarlet Crow of the Sisseton-Wahpeton Oyate band (then called the Sisseton-Wahpeton, one of the many bands that make up the Sioux tribe) had been staying at the barracks on the corner of New York Ave and 19th Street NW along with other members of the Native American delegation with whom he had traveled. No one knows for sure what led to Scarlet Crow’s disappearance, but there are different theories depending on who you ask. Sisseton-Wahpeton Oyate oral history proposed that he was kidnapped from the barracks, while the Evening Star newspaper put forth that he had simply wandered outside and gotten lost.

What is indisputable, however, is that after that night, Scarlet Crow was never seen alive again.

On February 17, several days prior to his disappearance, Scarlet Crow and other Sisseton-Wahpeton Oyate leaders came to Washington, D.C. from the Dakota Territory to negotiate a treaty with the U.S. government. They would be discussing the creation of a reservation for the Sisseton-Wahpeton Oyate band around Lake Traverse and Devil’s Lake in the eastern portion of the territory. For several days, the delegates spoke with Lewis V. Bogy, the Commissioner of Indian Affairs, and eventually settled on an agreement on February 19 in which the U.S. would give the Sisseton-Wahpeton Oyate land and annual payments.[1]

Two days later, however, the treaty was renegotiated.[2] The revised treaty removed several of the original articles which outlined specific land provisions and payments to the Sisseton-Wahpeton Oyate and added another article which promised that Congress would “in its own discretion, from time to time make such appropriations as may be deemed requisite to enable said Indians to return to an agricultural life under the system in operation on the Sioux reservation in 1862.”[3] According to Sisseton-Wahpeton Oyate oral history, Scarlet Crow protested the revisions and said to President Andrew Johnson, “These men are not chiefs,” when the other leaders agreed to sign the new document.[4] Although it still isn’t entirely clear why Scarlet Crow disappeared on the night of the 24th, it may have been those remarks that cost him his life.[5]

About a week after Scarlet Crow went missing, the government put an advertisement in the lost and found section of the Evening Star. It offered a reward to anyone who found the lost man or gave information regarding his whereabouts:

$100 REWARD – On Sunday night Feb. 24 [1867] one of the Indians belonging to the SissetonWahpeton Sioux delegation disappeared from the Barracks, corner of New York Avenue and 19th Street, and has not since been heard from. Said Indian is about 40 years old, and about five-feet-six inches high, and wearing his hair cropped. He had on when he left satinet pants, laced shoes, striped flannel shirt, and wore a green three-point blanket. The above reward will be paid to any person returning said Indian to the foresaid Barracks, or giving such information as will lead to his recovery, by applying to the Commissioner of Indian Affairs or to Benjamin Thompson, Special Agent, No.64 Kirkwood House.[6]

Over the next couple weeks, Scarlet Crow’s disappearance faded into the background of the public’s consciousness. The story wasn’t featured in the local news, and life continued as usual. Then, on the morning of March 12, two men from Alexandria, John Burch and Isaac Veitch, neither of whom seemed to have any connection to the treaty negotiations, reported an alarming discovery. They claimed to have found the body of a Native American man hanging from a tree branch near the Aqueduct Bridge in Arlington, VA, about two miles away from the barracks where the Sisseton-Wahpeton Oyate delegation was housed. It was Scarlet Crow.[7]

The Indian agent who had organized the Sisseton-Wahpeton Oyate delegation, Joseph R. Brown of Minnesota, and several investigators rushed to Virginia. Upon arrival, they noticed a few odd things about the crime scene. “The twigs to which the Indian was found would have bent under a forty pound weight; the strip of blanket around his neck was too weak to have sustained a child of five years of age – the knots which held the strip at both ends were never tied by an Indian,” wrote the investigators in a letter to their higher-ups.[8] He had also only been dead for a few days and appeared to be well-fed. They suspected that Scarlet Crow had been murdered and that the perpetrator or perpetrators had then tried to make it look like he had hung himself.[9]

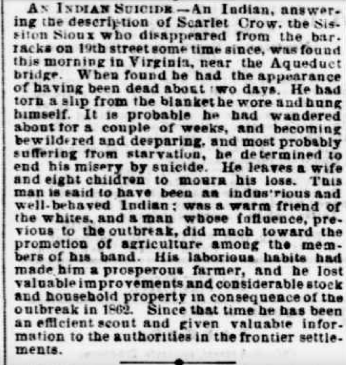

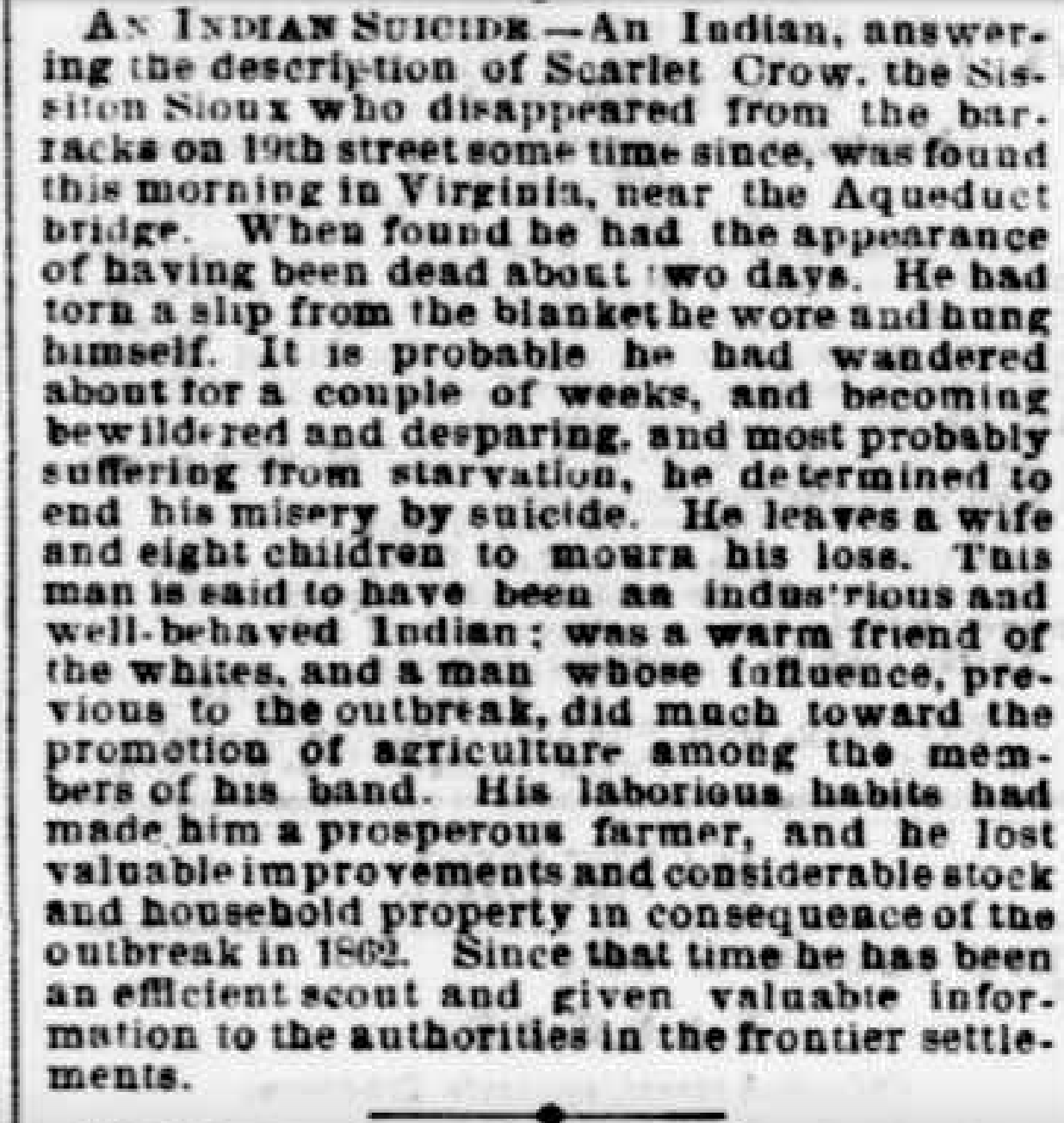

However, on March 12 the police report ruled Crow’s death a suicide, and the Evening Star reported it as such, stating:

“An Indian, answering the description of Scarlet Crow, the Sissiton Sioux who disappeared from the barracks on 19th street some time since, was found this morning in Virginia, near the Aqueduct bridge. When found he had the appearance of having been dead about two days. He had torn a slip from the blanket he wore and hung himself. It is probable he had wandered about for a couple of weeks, and becoming bewildered and desparing, and most probably suffering from starvation, he determined to end his misery by suicide.”[10]

Still, Brown thought it was a murder...but he didn’t want to set a precedent “under which other Indians would be kidnapped and hidden away until a reward was offered when he would be killed to prevent his making known the cause of his absence and the treatment he had received.” On the other hand, he didn’t wish “to be understood as charging either of the claimants [of the reward] to be perpetrators of so black and damnable a crime.”[11] There are no available resources that tell us why Brown decided not to press charges, but it could have been because he doubted the police would believe his hypothesis. Or, perhaps he was trying to avoid stirring up extra trouble over the death of a man the government viewed as a second-class citizen anyway due to his race. In the end, Burch and Veitch received $50 each, the case was closed, and there’s no record of anyone else following up on the investigation.[12]

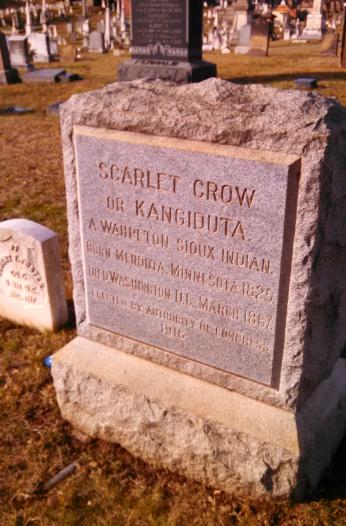

Scarlet Crow’s body was taken to Congressional Cemetery near Capitol Hill for burial the day after it was found. At the time, the grave was simply marked 76-R. A. 22, and the government gave his family $500 of trade goods in compensation.[13] Decades passed, and Scarlet Crow’s relatives requested on multiple occasions that the grave be properly marked with a headstone yet no marker was placed. Beginning in 1912, Scarlet Crow’s son Sam, a farmer in his mid-fifties living in North Dakota, petitioned Congress. Finally in 1916 - almost 50 years after Scarlet Crow’s mysterious death - a gravestone was placed at the urging of Republican Senator Asle Gronna from North Dakota.[14] The inscription read, “SCARLET CROW OR KANGIDUTA. A WAHPETON SIOUX INDIAN. BORN IN MENDOTA, MINNESOTA 1825. DIED IN WASHINGTON, D.C. MARCH 1867. ERECTED BY AUTHORITY OF CONGRESS 1916.”[15]

For the better part of the next 80 years, the mysterious circumstances surrounding Scarlet Crow’s disappearance again faded from the public consciousness. But, in 2001, his memory resurfaced in Washington. Inspired by an exhibit he had seen at the Library of Congress, Democratic Senator Byron Dorgan of North Dakota was curious to learn more about the man. With the help of his aides, he conducted further research on what had happened in February and March of 1867 in order to shed more light on the details. After going through letters between the Bureau of Indian affairs and the investigators as well as official reports, Dorgan shared his findings publicly on the Senate floor in April, 2001.[16]

He recounted the circumstances that led to Scarlet Crow’s death, from his arrival in D.C. to the evidence that seemed to point to a homicide rather than suicide. Dorgan conceded that there was more to the story that he couldn’t find - notably, what exactly happened between the time when Scarlet Crow disappeared and when he was found as well as how and when the man’s family heard about his death. In his concluding remarks, Dorgan lamented, “Since [Congress erected a headstone for his grave] nearly a century ago, the memory of Scarlet Crow has been relegated to obscurity.”[17]

While it’s true that most Americans had long forgotten the mysterious death of the Sioux chief, his memory continues to live on through Sisseton-Wahpeton Oyate oral history. A few years after Senator Dorgan’s tribute, several tribal members from the Sisseton-Wahpeton Oyate Tribal Historic Preservation Office traveled to the nation’s capital to visit Scarlet Crow’s grave. The purpose of their pilgrimage was to participate in an event at Congressional Cemetery hosted by the Faith and Politics Institute of Washington called “A Time of Rededication and Story-Telling.” But, rather than speaking about Scarlet Crow’s life as distant history on the day designated for story-telling, those who were present decided it was best to instead publish his life story in their tribal newspaper because, “his is a story with issues that have not been resolved. It remains a part of our present day lives and is not yet considered only history.”[18]

Footnotes

- ^ “Treaties with the Indians,” Evening Star, February 20, 1867, Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers.

- ^ “Ratified treaty no. 360, Treaty of February 19, 1867, with the Sisseton and Wahpeton Sioux Indians,” University of Wisconsin Digital Collections, accessed October 12, 2021, https://digicoll.library.wisc.edu/cgi-bin/History/History-idx?type=head….

- ^ “Treaty with the Sioux, Sisseton and Wahpeton Bands,” University of Tulsa, accessed September 16, 2021, http://resources.utulsa.edu/law/classes/rice/Treaties/15_Stat_0505_Siou….

- ^ “Kangi Duta and the Historic Congressional Cemetery,” Tamara St. John, Sota Iya Ye Yapi, June 16, 2010, https://www.sota-swo.com/Archives/2010/sota24.pdf.

- ^ Ibid. St. John from the Sisseton-Wahpeton Oyate Tribal Historic Preservation Office put forth the theory that Scarlet Crow’s objections to approving the amended treaty led to his death, likely at the hands of white Americans, based on “the belief of many...and as one elder said, “...so they killed him.””

- ^ “$100 Reward,” Evening Star, March 2, 1867, Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers.

- ^ “An Indian Suicide,” Evening Star, March 12, 1867, Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. U.S. House of Representatives, “Disbursements for Indian Service,” in House Documents (Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1868), 124.

- ^ St. John, “Kangi Duta.”

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ “An Indian Suicide.”

- ^ Herman Viola, Diplomats in Buckskins: A History of Indian Delegations in Washington City (Oklahoma: University of Oklahoma Press, 1995, 164.

- ^ “Congressional Record - Senate,” U.S. Government Publishing Office, April 5, 2001, https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/CRECB-2001-pt4/pdf/CRECB-2001-pt4-P…;

- ^ United States, Department of the Treasury, Bureau of Accounts, Digest of Appropriations for the Support of the Government of the United States for the Service of the Fiscal Year Ending June 30, 1917 and on Account of Deficiencies for Prior Years (Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1916), 385.

- ^ “Mark Indian’s Grave,” Bismarck Daily Tribune, March 28, 1914, Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers.

- ^ “Scarlet “Kan-Ya-Tu-Duta” Crow,” Find a Grave, October 24, 2006, https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/16306204/scarlet-crow.

- ^ “Congressional Record - Senate.”

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ St. John, “Kangi Duta.”

![Sketch of the mythical fuan by Pearson Scott Foresman. [Source: Wikipedia]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2023-10/Goatman_Wikipedia_Faun_2_%28PSF%29.png?h=64a074ff&itok=C9Qh-PE1)