Dinner and Debates: Boardinghouses of the District

Long before the invention of the airplane and a short time before trains were used for commercial transportation, congressmen traveling to Washington for extended periods faced a complicated issue: where would they live in the developing capital city while Congress was in session? Some wealthier members of Congress could purchase private residences or stay with a colleague, but this was not a realistic option for most. According to Byron Sunderland, former Senate Chaplain, “at that time hardly a prominent man connected with the general government had a house of his own in the city.”[1] The most common solution by far, was to reside in one of the District’s many boardinghouses.[2] Several former presidents, including Abraham Lincoln, found boardinghouses to be a phenomenally sufficient option during their congressional years— for a reasonable fee, a boardinghouse would provide you a room, quality meals, place to work (congressmen didn’t actually have their own dedicated office spaces until the early 20th century), and lively conversation with fellow residents, many of whom were also politicians.[3] Boardinghouses were scattered throughout the city, but the majority of them were located on Capitol Hill in the area where the Library of Congress stands today.

One of the most famous locations for boardinghouses was Carroll Row (also known as Duff Green’s Row). Located on First Street facing the Capitol Building, Carroll Row was a strip of Federal-style houses originally built by Daniel Carroll in 1805. Carroll was one of the original major landowners in Washington and owned most of the land that is now Capitol Hill. Hoping the value of this land would increase with L’Enfant’s proposed city layout, which had much of the residential development rising to the east of the Capitol, Carroll decided to invest in the construction of these houses to meet the growing need for boardinghouses.[4] Ironically, Carroll’s steep prices were likely a significant cause of why much of the city developed to the west of the Capitol. Nevertheless, Carroll Row was conveniently located for congressmen whose work commute was a simple walk across the street.

By far the most well-known residence on Carroll Row was Mrs. Spriggs’ boardinghouse. Widowed in 1833, Ann Sprigg opened a boardinghouse on New Jersey Avenue SE in 1834 to support her family.[5] She relocated to Carroll Row in 1839— then owned by Duff Green (editor of the United States Telegraph newspaper) who lived with his family in the end house and often dined at Mrs. Sprigg’s. In an 1842 letter to his wife, Theodore Weld, an early architect of the American abolitionist movement and frequent guest at Mrs. Spriggs, provided a detailed description of boardinghouse life:

“I will tell you how I am situated. Mrs. Sprigg’s is directly in front of the Capitol. The iron railing around the Capitol comes to within fifty feet of our door. Our dining room overlooks the whole Capitol Park which is one-mile around and filled with shade trees. I have a pleasant room on the second floor with a good bed, plenty of covering, a bureau table, chairs, closets—a good fireplace…the pitcher of milk [is] always at my place— graham bread and corn bread—mush once or twice a day—apples once a day and at dinner potatoes, turnips, parsnips, spinach with eggs, almonds, raisins, figs and bread puddings. Pies, cakes, I have of course nothing to do with.” [6]

In addition to a good room and good food, Mrs. Sprigg’s was known as the place where Whigs and abolitionists, like Theodore Weld, stayed. Although her husband, Benjamin Spriggs, was a slaveowner, the 1840 census shows that Ann Spriggs had only free black people living with her after his death, and there is good reason to believe that Mrs. Sprigg’s was something of an unofficial Underground Railroad stop.[7] Weld wrote of the house:

“We speak on the subject of slavery with entire freedom, nobody gain-saying us. Mrs. Sprigg, our landlady, is a Virginian not a slaveholder, but hires slaves. She has eight servants all colored, 3 men, one boy and 4 women. All are free but 3 which she hires and these are buying themselves…Mrs. Sprigg has now twenty five boarders, and here is a singular fact, and one that speaks well for Abolition in Washington - it is that for the last two years this has been known as the ‘Abolition house’: Giddings, Gates and Leavitt, abolitionists, and all the other boarders favorably inclined…Mrs. Sprigg thinks it quite unsafe to have slaves in such close contact with Abolitionists, so she has taken care to get free colored servants in their places! Stick a pin there.” [8]

With such divisive politics at play, there’s no question as to why Abraham Lincoln, perhaps the most famous guest of Mrs. Sprigg’s, would have elected to stay there as the sole Whig representative from Illinois during his 1847-1849 term in the House.[9]

Although he was joined, for the first 3 months, by his wife and two (rather raucous) young sons, cramped accommodations and a mutual disdain between Mrs. Lincoln and the other boarders caused Lincoln, who got along very well with the lot, to send his family back to Kentucky and spend the remainder of his congressional years at Mrs. Sprigg’s solo. (Lincoln wrote to Mary Todd a few weeks after her departure saying, “all the house – or rather, all with whom you were on decided good terms – send their love to you. The others say nothing.”[10])

Aside from any personal disputes, however, the spattering of politicians and lobbyists at D.C. boardinghouses lent itself rather nicely to lively dinner discussion. In an 1895 memoir, Samuel C. Busey, a young doctor who boarded at Mrs. Sprigg’s, recounted everything from Lincoln’s jovial storytelling to contentious political brawls at mealtimes:

“[I] took my meals at a boarding house kept by Mrs. Sprigg, occupying a seat at the table nearly opposite Abraham Lincoln, whom I soon learned to know and admire for his simple and unostentatious manners, kindheartedness, and amusing jokes, anecdotes and witticisms. When about to tell an anecdote during a meal he would lay down his knife and fork, place his elbows upon the table, rest his face between his hands, and begin with the words “that reminds me,” and proceed. Everybody prepared for the explosions sure to follow. I recall with vivid pleasure the scene of merriment at the dinner after his first speech in the House of Representatives, occasioned by the descriptions, by himself and others of the Congressional mess, of the uproar in the House during its delivery…The Wilmot Proviso was the topic of frequent conversation and the occasion of very many angry controversies. [John] Dick[ey], who represented the Lancaster district in Pennsylvania, afterward represented by Thaddeus Stevens, was a very offensive man in manner and conversation, and seemed to take special pleasure in ventilating his opinions and provoking unpleasant discussions with the Democrats and some of the Whigs, especially Thompkins, who held adverse opinions on the Wilmot Proviso…Mr. Lincoln, who may have been as radical as either of these gentlemen, but was so discreet in giving expression to his convictions on the slavery question as to avoid giving offence to anybody, and was so conciliatory as to create the impression, even among the proslavery advocates, that he did not wish to introduce or discuss subjects that would provoke a controversy. When such conversation would threaten angry or even unpleasant contention he would interrupt it by interposing some anecdote, thus diverting it into a hearty and general laugh, and so completely disarrange the tenor of the discussion that the parties engaged would either separate in good humor or continue conversation free from discord.” [11]

Mrs. Sprigg’s wasn’t the only politically charged boardinghouse on Capitol Hill. Just a few blocks over on the west side of 3rd Street between Pennsylvania Avenue and C Street was Mrs. C. A. Pittman’s, temporary home mostly to Democrats and Conservative Whigs.[12] Unlike neighboring boardinghouses, there was no alcohol at Mrs. Pittman’s, but many prominent politicians boarded there just the same, including future Presidents James Buchanan, Franklin Pierce, and Millard Fillmore.[13] An 1837 sketch of Mrs. Pittman’s by Representative Amasa J. Parker (NY-D), notably shows that the dining room and parlor for congressmen and their wives was separate from that of other boarders, implying that any “shop-talk” would stay relatively private.[14] With this detail in mind, one could imagine that the conversations amongst Democrats at Mrs. Pittman’s could get just as…enthusiastic as the Whigs down the street.

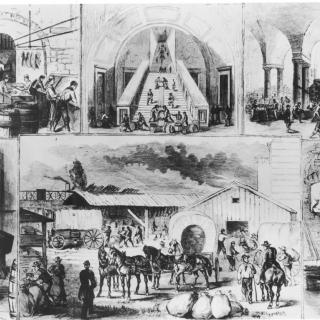

The commonality of boardinghouses faded in the wake of the Civil War. The houses on Carroll Row were used as an extension of the Union’s Capitol Prison (present site of the Supreme Court) for “contraband” slaves and prisoners during the War.[15] In 1887, the entire block was razed to begin construction of the Library of Congress. Even though these boardinghouses are now just a distant District memory, they undoubtedly played a significant role in shaping American history and politics, with some of the most poignant discussions of the 19th Century taking place at those dinner tables.

Footnotes

- ^ Byron Sunderland, “Washington as I First Knew It. 1852-1855,” Records of the Columbia Historical Society, Washington, D.C. 5 (1902): 195–211, https://www.jstor.org/stable/40066802.

- ^ William Minozzi and Gregory A Caldeira, “Social Influence in the U. S. House of Representatives, 1801-1861,” Ohio State University, May 16, 2015, 39, https://www.vanderbilt.edu/csdi/events/residences.pdf. pp 8-13.

- ^ “U.S. Senate: Meeting Places and Quarters,” accessed April 7, 2021, https://www.senate.gov/artandhistory/history/common/briefing/Meeting_Pl….

- ^ Kimberly Prothro Williams, “Capitol Hill - Historic District Brochure” (DC Historic Preservation Office), accessed June 16, 2021, http://dcpreservation-wpengine.netdna-ssl.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/1…. pp 5-6.

- ^ “Ann Sprigg Biography,” accessed March 5, 2021, http://bytesofhistory.com/Collections/UGRR/Sprigg_Ann/Sprigg_Ann-Biogra….

- ^ Jean H. Baker, Mary Todd Lincoln: A Biography (W. W. Norton & Company, 1987). pp 137-138.

- ^ “Ann Sprigg Biography.”

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Baker, Mary Todd Lincoln. p 137.

- ^ Baker. Mary Todd Lincoln: A Biography. p 138 ; Mac, “Mrs. Sprigg’s Amicable Boarder,” The Log Cabin Sage (blog), January 1, 2020, https://thelogcabinsage.com/mrs-spriggs-amicable-boarder/.

- ^ Samuel Clagett Busey, Personal Reminiscences and Recollections of Forty-Six Years’ Membership in the Medical Society of the District of Columbia and Residence in This City, 1895. pp 25-26.

- ^ Minozzi and Caldeira, “Social Influence in the U. S. House of Representatives, 1801-1861.” p 12.

- ^ Minozzi and Caldeira. p 12.

- ^ Minozzi and Caldeira. pp 12-13 ; “Image 1 of Illustrated Letter, Amasa J. Parker to Harriet Parker Describing the Boardinghouse Where He and Two Future Presidents Resided, 31 December 1837.,” image, Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. 20540 USA, accessed June 19, 2021, https://www.loc.gov/resource/mcc.084/?sp=1.

- ^ “Lost Capitol Hill: Duff Green’s Row - Lincoln,” The Hill Is Home (blog), August 11, 2009, https://thehillishome.com/2009/08/lost-capitol-hill-duff-greens-row-2/.

![Carroll Row, formerly located on present site of the Library of Congress. [No Date Recorded on Caption Card] Photograph. https://www.loc.gov/item/2016647982/.](/sites/default/files/styles/embed_full_width/public/carrollrow_loc2.jpg?h=9fae312c&itok=YynpBKIA)

![Sketch of the mythical fuan by Pearson Scott Foresman. [Source: Wikipedia]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2023-10/Goatman_Wikipedia_Faun_2_%28PSF%29.png?h=64a074ff&itok=C9Qh-PE1)