Time Travel in the "Virgin Vault": Washington’s Women’s Boarding House

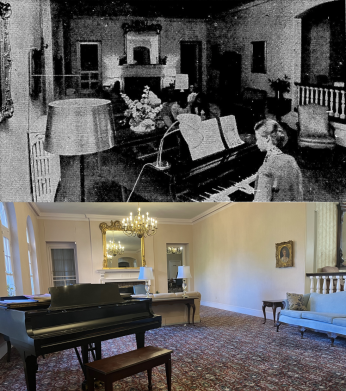

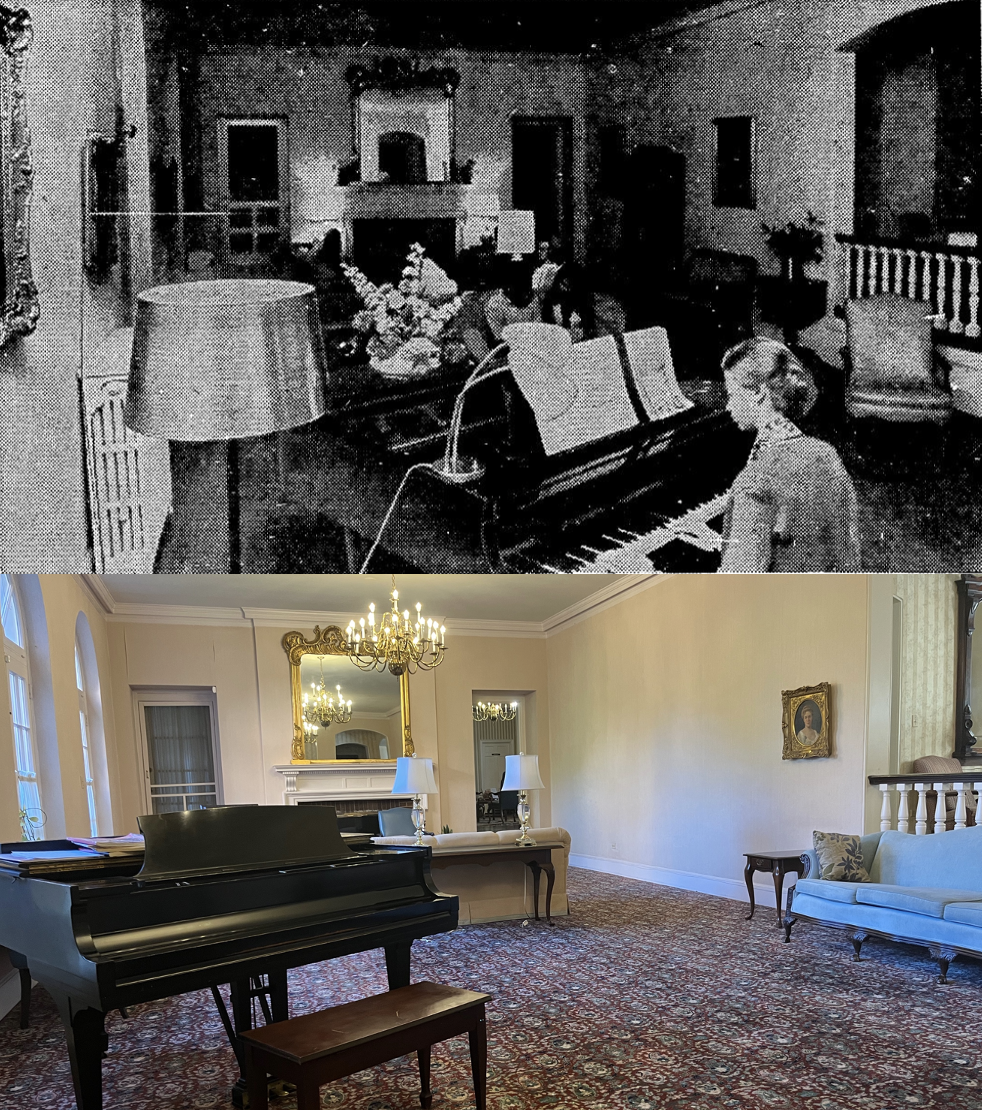

In an imposing brick building at 235 2nd Street, NE on Capitol Hill, time stands still. If you walked through the front door, you would find yourself in a parlor decorated with gilded antique mirrors and ornate rugs. Portraits of wealthy and influential benefactors decorate the walls. Sometimes music can be heard from the piano in the next room.

Further inside the building, around seventy young people gather in a living room and dining room (where they are not served if they are wearing nightclothes or slippers). On the upper floors are dorm-style single bedrooms and shared bathrooms. In each room, a resident sleeps in a twin bed decorated with a floral bedspread, and inside every nightstand there is a Bible. Oh, and there are no men allowed beyond the first floor. No boyfriends, brothers, or dads. No. Boys. Allowed.

You might think you’ve walked through a portal back into the 1910s, but this is a present-day reality for the current residents of Thompson-Markward Hall, a women-only boarding house on Capitol Hill. On its website, Thompson-Markward Hall (TMH) tells potential residents, “Peek in the front door of TMH and here’s what you might think — wow, time travel is real.”[1] So let’s do some time travel!

TMH began as the charitable dream of one woman, Mary G. Wilkinson. Wilkinson and her husband were grieving the death of their daughter when she met two young women at her church in 1833.[2] The women were new to Washington and living in a boarding house that “did not bear a good reputation.” So Wilkinson opened her home to them while she helped them find better housing.[3] Seeing that this was an indication of a broader need, Wilkinson purchased “a very small and cheap house” nearby to establish a women-only boarding house.[4]

In 1887, the boarding house was incorporated by Congress under the name Young Women’s Christian Home[5] and it received federal funding until 1906[6] along with donations from local Washingtonians and charitable organizations.[7] For the first several decades of its existence, it was primarily a charity for women who could not afford to live elsewhere. Despite the “Christian” in its original name, TMH was “strictly non-secretarian [sic].”[8] A “worthy, penniless girl” could stay for up to ten days for free, or longer if she was in dire need, and could pay her way by assisting with household tasks.[9]

The idea was both novel and completely un-original at the same time. Boarding houses had been a big part of Washington life since the District’s creation. When Wilkinson opened hers, it was one of 160 across the city – and those numbers grew during the early 20th century.[10] These homes served everyone from poor young people to congressmen who did not want to establish a permanent home in Washington.[11]

Wilkinson’s home was more than just a boarding house, however. Compared to most others, it took a larger role in looking out for its residents and helping position them for success in Washington. During its early years, TMH had a staff that included a superintendent, or “matron,” to care for the residents.[12] As the home grew, it had a director and a Board of Trustees who helped to fundraise and make major decisions about upkeep.[13] Cooks and housekeepers kept the residents fed and other staff helped the women secure employment and future housing. They also offered cooking and sewing classes to help the women bolster their employment prospects.[14]

Though TMH branded itself as a home for “respectable poor young women,”[15] it was actually a home for women of all stripes. Some early TMH residents were running from the law, chasing a lover, escaping unsatisfactory home life, struggling with mental illness, or just looking for a fresh start.[16] The matron, along with the home’s Committee on Reference and Employment, determined if a woman was eligible to stay—and those decisions were not always easy. As the vice president of the home’s board remarked in 1904, “It has been most hard to say ‘no’ when some friendless orphan from the pine forests of Maine or some gentlewoman from the sunny south has asked our protection and aid.”[17]

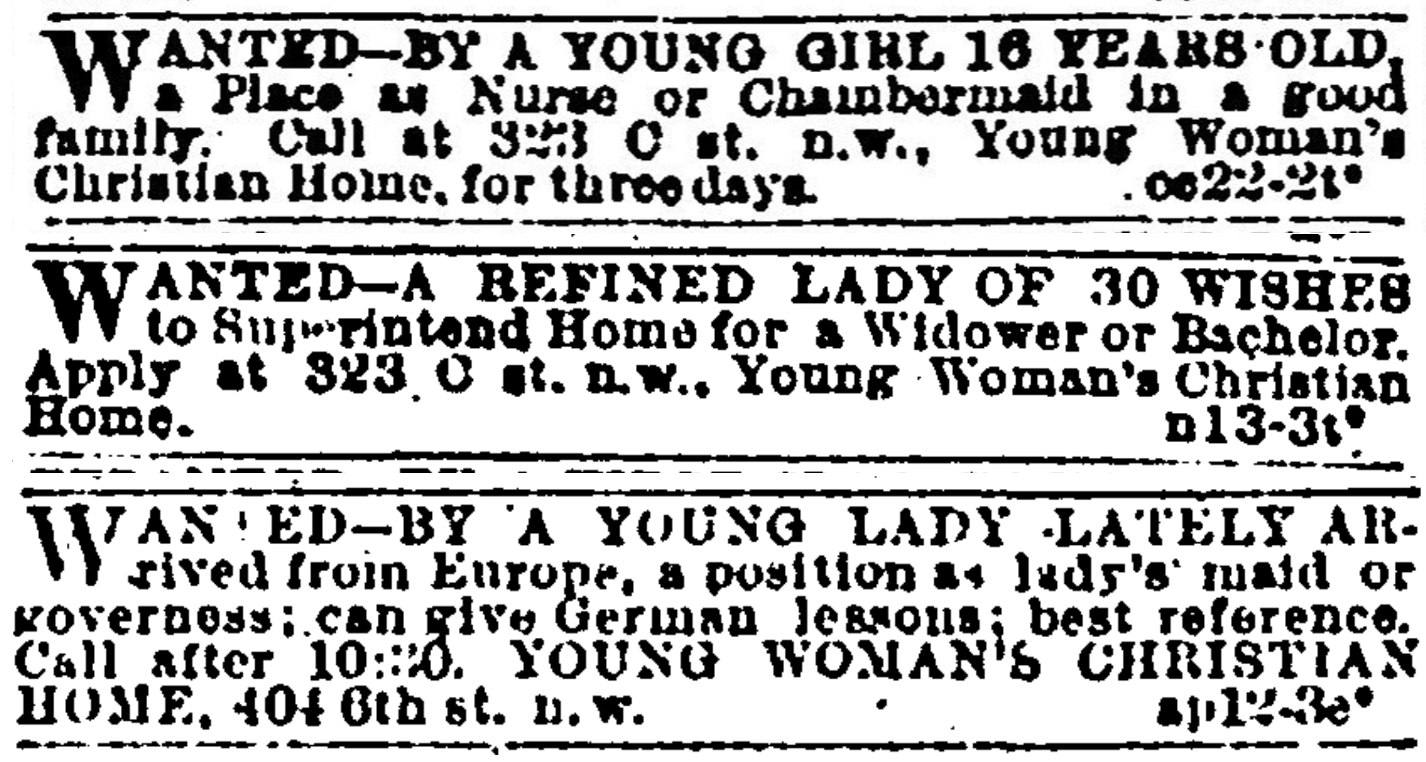

As the vice president alluded, the stakes were high. Prospects for a single woman in Washington during the late 19th and early 20th centuries were challenging. The nation’s capital was—as the Evening Star remarked in 1904 – a “mecca of the unemployed”[18] and many women living in TMH were job hunting. Most were seeking domestic positions such as nannies and chambermaids[19] as domestic work was seen as most “appropriate” for single women during this time.[20]

Industrialization created more jobs outside of the home for women[21] and Washington experienced growing pains from the employment booms and busts that came with both World Wars and the Great Depression. Overall, women’s opportunities in Washington increased. During wartime, women living at TMH may have worked as telegraph operators, stenographers, or secretaries for domestic and foreign officials.[22] After the end of each war, most industrial jobs were returned to men, but clerical jobs in Washington’s expanding government agencies remained women’s work.[23] Even as the city was growing and more opportunities opened to women, the care and support that made TMH appealing to residents (and their faraway families) in the 1880s continued to set the home apart in the 20th century.

TMH moved to its present location on 2nd Street, NE in 1934, thanks to a significant donation from the estate of Washington socialite Flora Markward Thompson.[24] The home’s name was changed from the Young Women’s Christian Home to Thompson-Markward Hall to commemorate the gift, and the dedication ceremony of the new building boasted a special guest: First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt.[25]

Three years later, Roosevelt returned to celebrate the home’s fiftieth anniversary, where she spoke of the important role that TMH and other women-only boarding houses played in Washington:

“The value of this home is in the personal touch and in the security that it offers to the girls who come here to live. So many of our young people are troubled today by insecurity. They have a feeling that conditions are changing, that the world about them is changing. It is different when they have no parents if they have a home like this, a personal touch in that home, and some one to whom they can go when they feel unhappy or when they are very happy. It gives them a great satisfaction… A home like this keeps young people from being bitter.”[26]

The changing world that Roosevelt observed in 1937 would impact TMH in the decades to come. Though the appearance of the home remained largely the same, the lives of the women inside it changed. Fewer women lived there for charity, and more came for jobs in government and other Washington institutions. By the 1970s, more Americans than ever were graduating from college, and internships in government and other organizations became more common.[27]

Other women-only boarding houses in Washington struggled to stay open during this time, but TMH kept ahead of the competition with its lower rent and prime location on Capitol Hill.[28] It wasn’t immune to financial pressure, however, and perhaps for that reason TMH had a brief stint as a co-ed house in 1975. It quickly realized that it was no match for rowdy teenage boys and went back to being women-only!

By 1977, the Evening Star wondered whether TMH’s days might be numbered. “In the day of coed college dorms, some might think that the era of the respectable all-women’s hotel with the near archaic regulation of ‘no men above the first floor’ has come to the end… Some might think that [TMH’s] market—unattached women seeking a sheltered environment in a ‘home away from home’—has grown too sophisticated for the clinging remnants of an age when ‘nice’ girls were properly chaperoned.”[29]

If that author thought TMH seemed old-fashioned in 1977, she might be surprised to learn that fifty years after the article was published, Thompson-Markward Hall is not only still in existence, but that not much has changed.

Today, TMH markets itself as “a safe, affordable place for young women to live while pursuing their dreams here in DC.”[30] Residents are interns on Capitol Hill, graduate students at local universities, recent graduates beginning their careers, and everything in between. In the early 2000s, the home earned the unfortunate nicknames “The Virgin Vault” and “The Nunnery” from Hill interns.[31] Many current residents (somewhat) affectionately call it “The Convent.”

Now over 140 years old, TMH has remained remarkably consistent – and durable – even as the landscape and work culture of Washington has changed dramatically all around it. Looking into the future, it is difficult to say whether the old building on 2nd St. NE will continue to be the time capsule it is today. But if past is prologue, we wouldn’t bet against it.

Author’s note: I took an interest in writing about this subject because I am currently a resident at Thompson-Markward Hall. It is because of the affordable and flexible housing that TMH provides that I have been able to live and work in Washington as a recent college graduate.

Footnotes

- ^ "About Us,” Thompson-Markward Hall, Accessed Oct 11, 2022.

- ^ “Mrs. Roosevelt Speaks Today,” The Evening Star, April 18, 1937.

- ^ Proctor, John Clagett, “Old Unitarian Church Became a Court,” The Evening Star, April 20, 1930.

- ^ “The Wilkinson Home” The Racine Daily Times (Racine, WI) Jan 10, 1895.

- ^ Dodge, W.C., “Home for Unfortunate Women,” The Evening Star, Jan 31, 1891.

- ^ “Recognizing Thompson-Markward Hall,” Congressional Record—Senate, Vol. 158, Pt. 11, Nov 13, 2012.

- ^ Ibid.; “Young Women’s Christian Home,” The Evening Star, Nov 19, 1895.

- ^ "Miss Kibbey's Gift," The Evening Star, Jan 13, 1894.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Boyd, E. S., Boyd, A., Boyd, W. Henry., R.L. Polk & Co. Boyd's directory of the District of Columbia. Washington: R. L. Polk & co.

- ^ Tom Lewis, Washington: A History of Our National City, (New York, NY: Basic Books), 2015, 361.

- ^ “Young Woman’s Christian Home,” The Evening Star, Oct 14, 1890; “Robberies Reported,” The Evening Star, Sept 25, 1896.

- ^ “Home for Unfortunate Women,” The Evening Star, Jan 31, 1891.

- ^ “Young Woman’s Christian Home,” The Evening Star, Mar 7, 1896.

- ^ “Funds for Relief,” The Evening Star, Jan 3, 1894.

- ^ “She Will Go Home,” The Evening Star, Aug 3, 1891; “Burden on District,” The Evening Star, Nov 17, 1910.

- ^ “Food and Shelter,” The Evening Star, Oct 1, 1904.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Classifieds, The Evening Star, October 22, 1889; November 13, 1889; April 13, 1893.

- ^ Alice Kessler-Harris, Out to Work: A History of Wage-Earning Women in the United States, Oxford University Press, 2003, 127.

- ^ Ibid., 77.

- ^ Lewis, 214-286.

- ^ Kessler-Harris, 220.

- ^ “J.W. Thompson Dead,” The Evening Star, Jul 11, 1901.

- ^ “Mrs. Roosevelt Dedicates Home,” The Evening Star, Apr 28, 1934.

- ^ “50th Anniversary of Home Marked,” The Evening Star, Apr 21, 1937.

- ^ Kessler-Harris

- ^ Dunson, Lynn, “Evangeline Closing, Other All-Women Hotels Boom,” The Evening Star, Apr 9, 1977.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ “About Us,” Thompson-Markward Hall, Accessed Oct 11, 2022.

- ^ Goldstein, Steve, “D.C. dorm-style residence has room for no men. Women relish distinctive dwelling,” The Philadelphia Inquirer, Aug 22, 2004.

![Sketch of the mythical fuan by Pearson Scott Foresman. [Source: Wikipedia]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2023-10/Goatman_Wikipedia_Faun_2_%28PSF%29.png?h=64a074ff&itok=C9Qh-PE1)