Respect, Unity, and Brotherhood at the Million Man March

If you visited any major U.S. city in the early fall of 1995, there’s no doubt you would have heard of the Million Man March for Black men in Washington, D.C., on October 16, either from flyers posted around town or through word of mouth.[1] After all, plans for a massive gathering of African American men on the National Mall had been in motion for over a year.

In June of 1994, Minister Louis Farrakhan first proposed the concept for a Million Man March on the National Mall at a meeting in Chicago for leaders of the various chapters of the Nation of Islam.[2] The idea was well-received, and the group decided to declare October 16 a national holiday for African Americans. It was to be a day of atonement in which Black people would not go to work or school, nor would they shop at white-owned businesses.[3] As Dr. Leo Edwards, who would fly from San Antonio to attend the march, later explained, “Minister Farrakhan said we need to gather up all of you guys to have this day of atonement for your sins and then utilize that and make it into something positive so that you can go back out into your communities and be better servants.”[4]

Unlike the 1963 March on Washington, the purpose of the 1995 event was not to address political injustices against the Black community. Despite what organizer Minister Louis Farrakhan described as the “policies of a right-wing dominated government determined to withdraw itself from the responsibility of providing immediate as well as long-term structural relief for those caught in the vise of the ongoing deindustrializing of American society,” the aim of this march (which was actually not a march but a gathering) was to show “the world a vastly different picture of the Black male.”[5]

In the five months leading up to the Million Man March, the D.C. Local Organizing Committee met bi-weekly, and one of its members, Dr. Benjamin Chavis, attested to the fact that the general public was “very energetic, enthusiastic, and efficacious” throughout the planning process. The Committee also had the unwavering support of Mayor Marion Barry, but despite all of this, the march still received pushback from the mainstream local media before, during, and after the event.[6]

Much of the negative coverage stemmed from Farrakhan’s involvement. The Minister was and still is an extremely controversial figure due to his virulent anti-Semitism and homophobia. Upset with the Nation of Islam’s (NOI) shift away from Black separatism in the 1970s, he gathered followers of his own in an effort to restore the movement’s original tenets. By late 1980s, Farrakhan’s group had become more prominent than the original organization.[7]

However, his hard line stances and bigoted remarks cast a shadow on the March in the minds of some African Americans outside the NOI, including Civil Rights leader-turned-Congressman, Rep. John Lewis of Georgia. In an essay featured in Newsweek during the week of the event, Lewis wrote, “I cannot overlook past statements by Louis Farrakhan--and others associated with the Nation of Islam--which are divisive and bigoted. Although its general goal of encouraging African American men to be responsible is sound, the march is fatally undermined by its chief sponsor.”[8] Other men didn’t feel the need to be present on the Mall because they didn’t think they had anything to atone for. To them, it didn’t make sense for all Black men to atone for the sins of a few, and that’s what they believed Farrakhan was asking them to do. In response to their criticisms, Farrakhan retorted, “That’s your problem. You are self-righteous fools.”[9]

Despite the criticism in some circles, thousands of people from around the country made plans to travel to Washington for the March. In the days leading up to the October 16 event, 2,500 buses parked at Robert F. Kennedy Memorial Stadium. Hundreds more pulled into the city between midnight and 4 a.m. that day to drop off passengers. Metro started running trains at 4:30 in the morning, an hour earlier than usual, and participants and regular commuters alike were told to expect delays due to massive crowds.

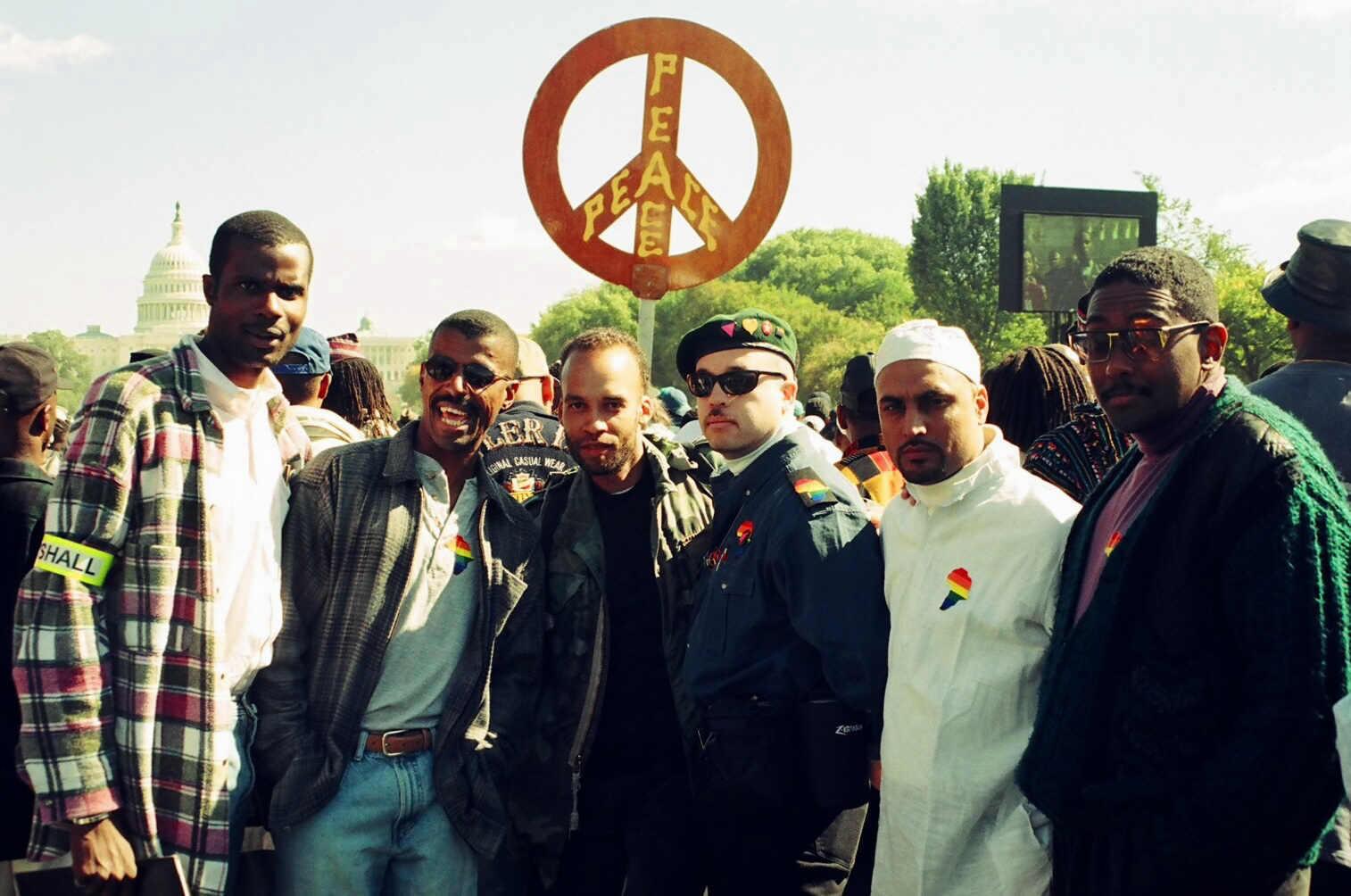

Although prayer services began at 5 a.m., the main program started at 11 a.m. and was expected to run until 8 o’clock in the evening.[10] By midmorning, thousands of Black men, many of them members of the growing Black middle class, gathered on the Mall. Over half of them had decided to attend more than a month in advance.[11] They walked around greeting each other as brothers, chatting, and posing for photos. Black women showed up in great numbers, too, and were welcomed despite being asked not to attend by organizers.[12]

The march’s attendees wandered through vendor tents selling t-shirts and buttons and munched on hot dogs from food stands.[13] As federal employee Tony Poole from New Jersey sat in the sun taking in the scene, he commented, “This is like the day before Thanksgiving. It's like you're waiting for your family and old friends to come home, and you're enthused. The only difference here is, it's people you've never met."[14]

Despite the controversy and attention surrounding Farrakhan, many of the men at the rally insisted that the event wasn’t really about the minister at all. According to one attendee, “This isn’t about Farrakhan, this is about respect, unity, and respect for the brothers. We’re tired of being behind everything, we want to be in charge sometimes, we want to unify, and that’s what this is about.”[15]

Louis Jennings, a truck driver from Kentucky, came because “I am black, but I also have a burglar alarm in my house and I live in a black neighborhood. I'm not worried about a Jewish boy climbing through my window.” If Farrakhan used hateful rhetoric that day, Jennings would simply ignore it. “Like eating poisoned food, I'll know what to spit out and keep in.”[16]

"The world has such negative images of us: We're all bad," said Christopher Crockett, a young paramedic from Chicago. "Most white people probably thought the Million Man March would result in damage and destruction, and we'd riot when Louis Farrakhan spoke. Finally, white people can see blacks do have strength in numbers, and in a good way."[17]

The march participants stood for hours at the foot of the stage set up in front of the Capitol as they listened to dozens of speeches from notable figures including Rosa Parks, Jesse Jackson, and Maya Angelou.[18] Several speakers echoed the idea that change had to come from Black men themselves. Teen orator Ayinde Jean-Baptiste exclaimed, “You must change today so that tomorrow may dare to be different. When you have fought back and regained your pride, when you have won some battles, when you are able to tell the stories of your heroism, when you can pass onto your young the tradition of struggle through examples of your having stood up for a better tomorrow, when you have taken control of our institutions...when you maximize our economic resources towards our own benefits...when you start teaching us to be humane, then we can build a new nation of strong people.”[19]

Dr. Dorothy I. Height, another keynote speaker and President of the National Council of Negro Women, harkened back to the Civil Rights Movement of the 1960s by contending that “The civil rights gains that we’ve thought were ours somehow are proving more tentative, and we’re finding that many of our young men and young women who went to jail singing “We Shall Overcome” have found that they have rights but they do not have the opportunity nor the economic position from which to pay the check. Let me say also that those who have benefitted from doors that have been opened...somehow have forgotten how those doors got opened, and I think the time has come for those who have made it to take the time to help lift the bottom.”[20]

Late in the afternoon, Farrakhan took to the podium as the final speaker, where he shared his thoughts about the root of the country’s racial divide: “The real evil in America is not white flesh, or Black flesh, the real evil in America is the idea that undergirds the setup of the Western world, and that idea is called white supremacy.” He went on to address the president, telling him, “We are a wounded people, but we are being healed. But President Clinton, America is also wounded, and there’s hostility now in the great divide between the people. Socially, the fabric of America is being torn apart. We are being torn apart, and we can’t gloss it over with nice speeches, Mr. President.”[21]

The key takeaway for most of the participants was that it was up to them to be the agents of change in Black communities. One way to do that, as Farrakhan outlined in his speech, was to vote, “Because in local elections you have to do that which is in the interest of your local community. But what we want is...a third force, which means that we're going to collect Democrats, Republicans, and Independents around an agenda that is in the best interests of our people….We're no longer going to vote for somebody just because they're black. We've tried that. We wish we could, but we've got to vote for you if you're compatible with our agenda.”[22]

For Atlanta banker George G. Andrews, creating change meant that “We must invest in our communities by fully supporting banks and businesses that are dedicated to our community. We must distinguish between those institutions and businesses that have a “take the money and run” attitude and those that are investing in the area, working aggressively for a positive future.”[23] To Alvertis Simmons of Denver, the next steps were even simpler. "Brothers, make this commitment. If you know a brother who is not paying child support, cut him off because he should be taking care of his kids," he told the Washington Times.[24]

That evening, many people left with a sense of accomplishment and optimism. However, others were skeptical of the march’s long term impact. Clara Day of Chicago admitted, “I was quite proud of the MMM but I don’t think marches will continue to be effective to rouse people into action. We’ll have to think of another way. We need to arouse the minds of young people now more than ever.”[25]

Larry Aubry expressed similar feelings in the Los Angeles Sentinel. He remarked, “The potential for extending the march’s covenant among black men to all of black America is the major challenge and extending the respect and bonding is the key to any real new beginning. Collective solidarity is a difficult long-range proposition and the required process of reconditioning will take a while.”[26]

In the days following the event, a different, more basic issue took center stage: were there actually one million men at the Million Man March? According to the U.S. Park Police, which did official crowd estimates for events on the Mall, the answer was no; there were only about 400,000 people present. The lower-than-advertised estimate led Farrakhan to denounce the National Park Service’s methods as an example of the “white-supremacist mindset.”[27] March organizers even threatened legal action against the NPS if it didn’t revise its original figure. The controversy swelled further when researchers at Boston University conducted another headcount via computer analysis of photos and videos taken at the march and came up with a much higher estimate ─ 837,000 ─ which was more than double the number of people reported by the Park Service.[28]

In the aftermath of the event, the Park Service and the Park Police got out of the business of estimating crowd sizes on the Mall ─ something it had been doing since the 1960s. In fact, the 1997 appropriations bill for the Department of the Interior specifically prohibited the NPS from conducting crowd estimates. The change came as a relief to some within the agency. As David Barna, chief of public affairs for the Park Service told the Washington Post a year after the Million Man March, “It has always been a thankless job for the Park Service… Every organization would always cry foul, saying the numbers should be larger.” Park Police Maj. J.J. McLaughlin agreed, "It got to the point where the numbers became the entire focus of the demonstration," McLaughlin said. "If people want crowd estimates, let them hire someone to do it."[29]

Regardless of the exact number of faces in the crowd, it was undeniable that the Million Man March succeeded in bringing together Black men from different states and backgrounds in a fraternal celebration of Black masculinity. Adrienne T. Washington, one of the many women present that day, reflected in the Washington Times, “Just for one day, black men looked one another in the eye and smiled. They spoke to one another at length and without fear. They held on to their sons, hugged their fathers and wrapped their arms around total strangers. If for no other reason, the Million Man March should be remembered as the day that masses of black men came together and walked away as brothers.”[30]

Footnotes

- ^ “Path to “Visible Glory”: The Million Man March in the Redmond Collection,” Southern Illinois University Edwardsville, accessed November 14, 2021, https://www.siue.edu/lovejoy-library/tas/MMM_exhibit_p4.htm.

- ^ Vanguard Television, “The Million Man March: The Untold Story With Minister Louis Farrakhan,” YouTube video, 33:00, January 15, 2018, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SLo1oXBmfs8. “Path to “Visible Glory.””

- ^ Vanguard Television, “The Million Man March.”

- ^ KSAT 12, “Two brothers reflect on Million Man March 25th anniversary through documentary,” YouTube video, October 17, 2020, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0WM3_lEmM38.

- ^ Ernest Allen, Jr., “The Farrakhan Speech: Toward A "More Perfect Union": A Commingling of Constitutional Ideals and Christian Precepts,” The Black Scholar 25, no. 4 (Fall 1995): 28. Larry Aubry, “Million Man March: A Moment or a Beginning?” Los Angeles Sentinel, November 2, 1995, A1.

- ^ Stacy M. Brown, “Million Man March Director Ben Chavis Recalls Historic Event: African Americans Pause and Look Back 25 Years Ago,” Washington Informer, October 14, 2020. https://www.washingtoninformer.com/million-man-march-director-ben-chavi….

- ^ “Louis Farrakhan,” Southern Poverty Law Center, accessed October 1, 2021, https://www.splcenter.org/fighting-hate/extremist-files/individual/loui….

- ^ Sam Fulwood III, “Farrakhan Calls Men Shunning March ‘Fools,’” Los Angeles Times, October 15, 1995. https://www.latimes.com/archives/la-xpm-1995-10-15-mn-57271-story.html.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ “The Million Man March: Questions and Answers About Monday’s Event,” Washington Post, October 14, 1995, C4.

- ^ Mario A. Brossard and Richard Morin, “Leader Popular Among Marchers,” Washington Post, October 17, 1995.

- ^ Brian Blomquist, “Million Man March hits 400,000 - Blacks get together for day of atonement,” Washington Times, October 17, 1995, A1.

- ^ “Marchers come in peace - Rally runs smoothly, without traffic hassles,” Washington Times, October 17, 1995, C4.

- ^ Brian Blomquist, “Marchers tall on arrival - Black men eager to take a stand together, whatever their politics,” Washington Times, October 16, 1995, C4.

- ^ AP Archive, “USA : WASHINGTON: THOUSANDS OF BLACK MEN JOIN MILLION MAN MARCH,” YouTube video, 1:47, July 21, 2015, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Wd-UsjThe58.

- ^ Blomquist, “Marchers tall on arrival,” C4.

- ^ Blomquist, “Million Man March hits 400,000.”

- ^ Connie Cass, “AP Was There: 20 years ago the Million Man March drew many to DC,” AP News, October 9, 2015, https://www.washingtonpost.com/local/million-man-march-anniversary/2020…. AP Archive, “USA: THOUSANDS OF BLACK AMERICANS MARCH ON CAPITOL HILL,” YouTube video, 0:32, July 21, 2015, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=JQPbv_OalQ8.

- ^ Anthony Edwards, “Episode 1. 25th Anniversary of the Million Man March,” October 16, 2020. San Antonio delegation in DC,” YouTube video, 11:08, October 13, 2020, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=pxXjwLinXYY. “Ayinde Jean-Baptiste Speaking at the 1995 Million Man March ─ Million Man March @ 20 Years,” Oronde A. Miller, October 11, 2015, http://www.orondeamiller.com/archives/4736.

- ^ Anthony Edwards, “Episode 1. 25th Anniversary of the Million Man March.”

- ^ NBCUniversal Archives, “The Million Man March - October 16th, 1995,” YouTube video, August 30, 2015, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0EBQ0taYXtQ.

- ^ Allen, “The Farrakhan Speech,” 31.

- ^ George G. Andrews, “Lessons From Million Man March: Economic Empowerment Our Responsibility,” Atlanta Daily World, November 19, 1995, 4.

- ^ “On the Mall, a seed is planted,” Washington Times, October 18, 1995, A16.

- ^ Cathy O. Gardner, “A tale of two marches: Chicagoans find similarities, differences between '63 March, Million Man March,” Chicago Defender, January 13, 1996, 52.

- ^ Aubry, “Million Man March: A Moment or a Beginning?” A1.

- ^ Michael A. Fletcher and Hamil R. Harris, “Million Man March Gets Another Head Count,” Washington Post, October 25, 1995, https://www.washingtonpost.com/archive/local/1995/10/25/million-man-mar….

- ^ Richard Lorant, “Experts Lower Estimates For ‘Million Man March’ Turnout to 837,000,” AP News, October 27, 1995, https://apnews.com/article/dfbbf95633bf31d3e8357d8ed3b37592.

- ^ Fletcher and Harris, “Million Man March Gets Another Head Count.” Leef Smith and Wendy Melillo, “If It’s Crowd Size You Want, Park Service Says Count It Out,” Washington Post, October 13, 1996, https://www.washingtonpost.com/archive/politics/1996/10/13/if-its-crowd….

- ^ Adrienne T. Washington, “Ordinary black men made day special,” Washington Times, October 17, 1995, C2.

![Sketch of the mythical fuan by Pearson Scott Foresman. [Source: Wikipedia]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2023-10/Goatman_Wikipedia_Faun_2_%28PSF%29.png?h=64a074ff&itok=C9Qh-PE1)