Why 17 Confederate Soldiers Were Buried on Georgia Avenue: The Battle of Fort Stevens

160 years ago, the only Civil War battle fought inside the District of Columbia nearly determined the fate of the nation. On July 11-12, 1864, Confederate forces under the command of Lieutenant General Jubal Early advanced down the 7th Street Pike (today Georgia Avenue, NW) and squared off against a motley crew of Union defenders garrisoned at Fort Stevens, one of the dozens of forts and batteries ringing the capital.

President Abraham Lincoln himself famously came under fire from enemy sharpshooters as he watched the fighting from the fort’s parapets, prompting a number of other individuals present, among them future Supreme Court Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr., to claim they shouted “get down” at the commander-in-chief.1 Had Lincoln been killed or the battle lost—resulting in the capture of Washington and disastrous political consequences—some historians argue the outcome of the war and the U.S. itself may have looked very different.

On Saturday, July 13, 2024 reenactors, musicians, and the public gathered to commemorate the anniversary of the little-known battle that saved Washington and reflect on the soldiers and civilians—black and white—that built and manned the city’s Civil War defenses.

“It was an incredibly close call and we are all incredibly lucky,” said Gary Thompson, president of the Alliance to Preserve the Civil War Defenses of Washington, who also portrayed Union Major General Lew Wallace at the anniversary event. “If [Early] had arrived on July 10 or early on July 11, surely he would have smashed through these defenses, really walked right over them.”

By the start of 1864, Washington was one of the most heavily protected cities in the world, home to some 60 forts, 93 batteries, and 837 artillery pieces guarding every strategic approach.2 But in order to lay siege to the Confederate army at Petersburg, Virginia that summer, Ulysses S. Grant had sent most of Washington’s veteran defenders south, leaving behind a rag-tag contingent of “semi-invalid Veteran Reserves, trainees, 100-day levies and a small cadre of experienced troops.”3

Perhaps luck more than anything played the decisive role in saving the city. After leaving Petersburg June 12, with orders from Lee to attack Washington in order to relieve pressure on the besieged Confederates, Early’s troops were held up by General Lew Wallace on July 9 at the Battle of Monocacy near Frederick, Maryland.4 Though the Confederates reached Silver Spring by midday on the 11th, Early withheld his main attack to rest his exhausted troops, who drank stolen wine and whiskey as they withered under a historic DC heat wave that kept temperatures in the mid-nineties.5

The delay allowed just enough time for Union reinforcements to arrive from Virginia via steamboat and rush through the city to bolster the beleaguered Fort Stevens. After skirmishing in front of the fort—and President Lincoln—on July 12, Early decided taking the city would prove too costly and withdrew after the two sides had suffered an estimated 874 killed and wounded.6 Had Early attacked sooner, his 10,000-strong force may very well have overpowered a roughly equal number of Union troops left defending the city.

“That was the true high-water mark of the Confederacy, not Gettysburg,” Civil War scholar Benjamin Franklin Cooling told the crowd assembled for the Fort Stevens anniversary. “I would suggest to you this high-water mark [down Georgia Avenue] was maybe what we should be talking about more and instilling in the minds of historians.”

“The Civil War can mean different things to different people, then and now,” Cooling added, in reference to disputes over the turning point of the war. In the century and a half since Fort Stevens, debates have also surrounded how the battle’s Confederate participants were commemorated. If the Battle of Fort Stevens itself is an understudied chapter of Civil War Washington, even less known is the role it played in generating local Lost Cause mythology.

Forty Union soldiers slain defending Fort Stevens were interred soon after the battle on a one-acre plot at 6625 Georgia Ave, still honored today as Battlefield National Cemetery, one of the country’s smallest national cemeteries.7 What happened to the bodies of Early’s dead Confederates is more complicated and intimately tied to the history of Grace Episcopal Church in Silver Spring.

Today, 17 Confederates killed at the battle are interred at Grace’s cemetery at the corner of Georgia Avenue and Grace Church Road, but they were not, as one 1965 church history book claimed, buried there in 1864.8 More than a decade after the battle in December 1874, Rev. James Battle Avirett, Grace’s third rector and a former Confederate Army chaplain, and his fellow “friends of the ‘lost cause’” organized the removal of the soldiers’ remains from their original resting spot “on a farm near the fort where they fell” to the church property, according to an Evening Star article.9

After the bodies were exhumed and placed in “six plain coffins” they were transported to the church yard, where some 300 local Marylanders and Washingtonians gathered for a service in honor of the fallen Confederates.10 Of the 17 soldiers reburied, only James B. Bland of the 62nd Virginia Mounted Infantry was known by name.11

Inside the Grace rectory, Alexander Yelverton Peyton Garnett—a Virginia-born surgeon who served as a physician to Robert E. Lee and other prominent Confederate generals during the war—delivered a keynote address that “justified the south for their action” and “alluded to the willingness of the south to take up arms to defend their homes from invasion.”12 One voice in the crowd responded “And we are still willing to do it, Dr.,” reported the Evening Star, which added that Garnett “alluded to the south as ‘our people’ and Jeff Davis as ‘our President.’”13

The reinterment ceremony at Grace came as part of a larger postwar effort to build Confederate memorials and promote Lost Cause narratives that deified Southern leaders and portrayed slavery as a benign institution (while denying its role in secession).

“[The Lost Cause] was putting into bricks and mortar this desire to remember the Confederacy as something honorable and hallowed,” said Elizabeth Boyd, a Grace Church parishioner and historian of the American South whose book Southern Beauty examines how certain gender rituals further entrenched racism and classism. “[Avirett] was very much a Confederate sympathizer so it's not surprising that he would want to give these remains a home.”

Despite remaining in the Union during the war, Maryland’s status as a border and slave state split residents’ sympathies during the war, with 60,000 Marylanders fighting for the North and 25,000 joining Confederate forces.14 Grace, like many DC-area churches at the time, also harbored both Union and Confederate loyalties amid its pews.

In 1896, the same year Plessy v. Ferguson ruled in favor of racial segregation and sparked a new surge in Confederate monument building, a 9-foot granite obelisk was installed at the corner of the Grace cemetery to mark the soldiers’ remains.15 Inscribed with the word “Confederate” at its base, the monument stood in place until the night of June 17, 2020, when unknown individuals toppled it and left behind an anonymous sign reading: "here lies 17 dead white supremacists who died fighting to keep black people enslaved.”16

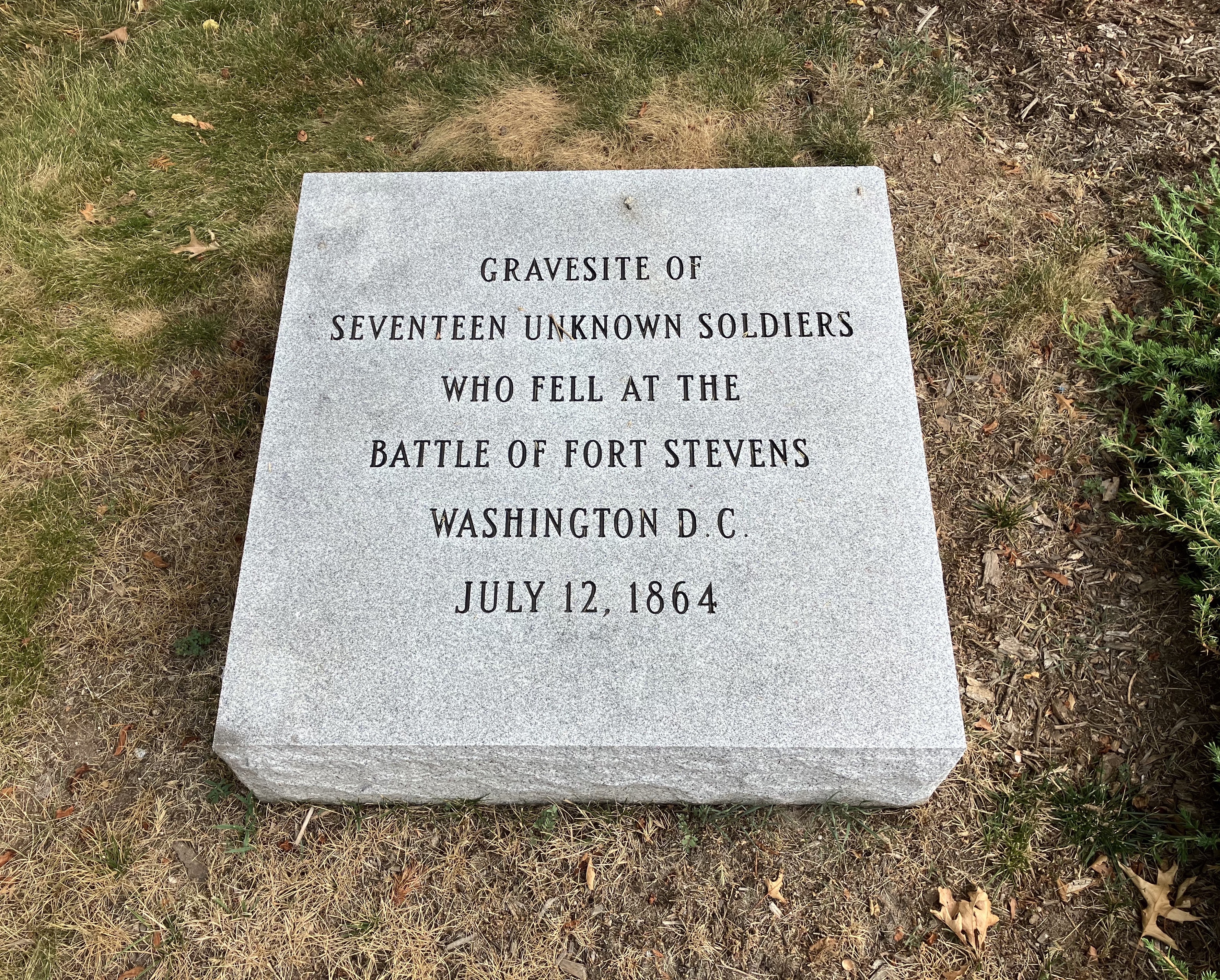

After the incident, the parish decided not to re-erect the obelisk and put in its place a small stone plaque acknowledging the “seventeen unknown soldiers” buried there. Standing in between the stone and Georgia Avenue now is a large “Black Lives Matter” sign. While Grace already had an active racial justice ministry, in 2021 the church also launched a Parish History of Race and Racism Team to better understand its past ties to white supremacist institutions.

“The parish has really encouraged our work and been very interested in it,” said team leader Susan Schulken.

Using census records and surveys conducted for the District of Columbia Compensated Emancipation Act of 1862, the researchers have identified over 70 men, women, and children enslaved by Grace’s land donor, vestry, and earlier parishioners.17 The team has also hosted a series of forums on parish history dispelling myths that whitewashed the church’s founding and relationship to slavery and the Confederacy.

One such myth that persisted well into the twentieth century was that Jubal Early noticed the church standing with no roof as he marched down the turnpike en route to Fort Stevens. Moved by the scene, Early supposedly sent the parish a $100 check to complete the building following his invasion.18 So entwined was Early with church lore that the parish installed a stained-glass representation of him holding a Confederate flag opposite a window of Union Major General George Washington Getty.

Yet according to diocese reports the original church building and roof were completed by at least May 1864 and there are no historical records linking Early to the Grace community.19 In 2017, the parish removed the Early window and replaced it with one depicting Madison Broadnax, a parish member and former Tuskegee airman who died in 2005. As Grace continues to embrace diversity and inclusivity in the present, the history team hopes to further separate facts from the fiction of its Fort Stevens and Lost Cause connections.

“Until you know your history, you don't really know who you are,” Schulken said. “You really sort of have to know your past in order to plan what you want to do in the future.”

Footnotes

- 1

“President Lincoln Under Fire at Fort Stevens,” U.S. National Park Service.

- 2

Benjamin F. Cooling, “Washington's Civil War Defenses and the Battle of Fort Stevens,” American Battlefield Trust, 21 April 2009.

- 3

Benjamin F. Cooling, “Washington's Civil War Defenses and the Battle of Fort Stevens,” American Battlefield Trust, 21 April 2009.

- 4

“Fort Stevens,” U.S. National Park Service.

- 5

Judge, Joseph (1994). Season of Fire: The Confederate Strike on Washington. Berryville, Virginia: Rockbridge Publishing Company. Pg. 216

- 6

“Fort Stevens,” American Battlefield Trust.

- 7

“Battleground National Cemetery,” National Park Service.

- 8

Mildred Newbold Getty, To Light the Way: A History of Grace Episcopal Church, Silver Spring, Maryland (Grace Episcopal Church 1965), 9.

- 9

“Confederate Dead Removal of Remains To-Day,”Evening Star (Washington, D.C., 11 December 1874).

- 10

“Confederate Dead Removal of Remains To-Day,”Evening Star (Washington, D.C., 11 December 1874).

- 11

“Confederate Dead Removal of Remains To-Day,”Evening Star (Washington, D.C., 11 December 1874).

- 12

“Confederate Dead Removal of Remains To-Day,”Evening Star (Washington, D.C., 11 December 1874).

- 13

“Confederate Dead Removal of Remains To-Day,”Evening Star (Washington, D.C., 11 December 1874).

- 14

“Confederate Dead Removal of Remains To-Day,”Evening Star (Washington, D.C., 11 December 1874).

- 15

“Grace Episcopal Cemetery & Confederate Monument,” Maryland Historical Trust Determination of Eligibility Form, 25 January 2013.

- 16

“Confederate memorial by Silver Spring church toppled,” WUSA (Washington, D.C., 18 July 2020).

- 17

- 18

“Telling Our Stories: Grace Church During the Civil War,” Grace Episcopal Church.

- 19

“Telling Our Stories: Grace Church During the Civil War,” Grace Episcopal Church.

![Sketch of the mythical fuan by Pearson Scott Foresman. [Source: Wikipedia]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2023-10/Goatman_Wikipedia_Faun_2_%28PSF%29.png?h=64a074ff&itok=C9Qh-PE1)