Phyllis Schlafly and the End of the Equal Rights Amendment

The eyes of Washington’s political class laid upon the Shoreham Hotel on the evening of June 30, 1982. The hotel, which has hosted singer Aretha Franklin, Bob Hope, Eartha Kitt, and every presidential ball from Franklin D. Roosevelt to Barack Obama, was about to open its doors to some of the most significant figures of the American conservative movement in the latter half of the twentieth century.[1]

With its ballroom filled with clusters of balloons and patriotic music humming in the air, over a thousand guests entered the hotel that night to mark “the expiration of the Equal Rights Amendment and the commencement of a new era of harmony between women and men.”[2] The host of the party was none other than “the sweetheart of the silent majority,” Phyllis Schlafly.

For over a decade, Schlafly was an outspoken activist against the adoption of the ERA into the Constitution. The amendment, approved by the Senate on March 22, 1972, was intended to guarantee equal legal rights to all women, and at the time was assured to succeed. But in what seemed like a sudden turn of events, Schlafly organized a national opposition movement of conservative women that brought momentum for the ERA to a dead stop. And as the amendment deadline of June 30, 1982, approached without the required three-fourths (38) ratification of all state legislatures, it was clear that Schlafly and her followers had won the battle.

To celebrate the end of the ERA, Schlafly decided to hold a party at the Shoreham Hotel on the day of the deadline—in an event that symbolized the arrival of a new era of conservatism in American politics.

Schlafly’s countermovement was so successful, in fact, that many in the political and media class attributed the demise of the ERA to her alone. And on the evening of the 30th as Schlafly descended the Shoreham Hotel’s Ambassador Room, draped in a white dress with butterfly sleeves, she surely believed this narrative as well, calling her own victory “the most remarkable political victory of the 20th century.”[3]

But how could one person single-handedly defeat what would have been the 27th amendment to the Constitution?

Schlafly’s Origins

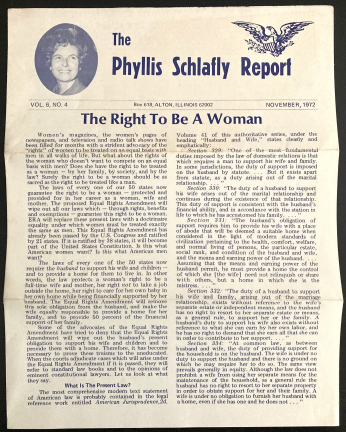

Schlafly’s status as the heroine of the conservative wing of the Republican Party came with the publication of her book A Choice Not an Echo in 1964. The book was written in support of Republican Barry Goldwater’s 1964 presidential campaign and sold over three million copies, presaging the conservative take-over of the Republican Party in the middle of the century. Later, in 1967, Schlafly launched her newsletter entitled the Phyllis Schlafly Report, where she mostly wrote about Cold War foreign policy.[4]

While she’s best known today for her role in the anti-ERA movement, many are surprised to hear that Schlafly wasn’t always a hawkish antagonist to it. According to Carol Felsenthal, her biographer, “if pressed, she might have supported it.”[5] And in Schlafly’s own words, she initially believed the ERA was “something between innocuous and mildly helpful.”[6] But after looking into it further, Schlafly concluded that the ERA held the roots of something much more dangerous.

Building a Countermovement

In February 1972, Schlafly published her first newsletter against the ERA, warning readers that it held the potential for great harm to women.[7] Among the charges against it were that it would subject women to the military draft and remove child support rights. Later, Schlafly also asserted that the ERA would create a constitutional guarantee for abortion and legalize gay marriage (which helped fuel the anti-gay moral and legal panic of the late-1970s).[8] Such measures, Schlafly claimed, were hidden underneath the ostensibly straightforward text of the amendment itself, at the core of which was the following: “Equality of rights under the law shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any state on account of sex.”

The anti-ERA campaign was motivated by traditionalist, Christian, anticommunist, and conservative beliefs that stemmed from the post-war American experience and the tradition of turn-of-the-century anti-feminism and anti-radicalism. According to scholar Kirsten Delegard, within this tradition, women believed they were uniquely called upon to fight communism, female progressives, and centralized government.[9] Paradoxically, notes scholar Erin M. Kempker, this mission allowed conservative women to escape the norm of female domesticity and engage in political organizing “outside the home in order to defend the home.”[10]

As the second-wave feminist movement surged into the mainstream of American politics in the mid-1960s, it tied into many anticommunist fears associated with “sexual anxieties, particularly homosexuality, with political threats and domestic subversion,” writes Kempker.[11] The perceived threat to the traditional family and American society jolted a large contingent of conservative stay-at-home wives and mothers into action—women whom Schlafly would later rally for her cause. By playing up the image of the traditional housemaker, Schlafly could force a juxtaposition with the progressive vision offered by the women’s liberation movement, which she called “destructive of family living.”[12]

To fight back against the women’s movement and the push for the ERA, Schlafly established the anti-ERA organization “STOP ERA” (an acronym for “Stop Taking Our Privileges”) in September 1972.[13] Later, in 1975, she established another organization named Eagle Forum, which she called “the alternative to women’s lib.”[14]

Schlafly Comes to Washington

Throughout her anti-ERA campaign, Schlafly made frequent visits to Washington to state her case.

On one occasion, while giving a speech at the National Town Meeting at the Kennedy Center, Schlafly stated that to support the ERA is “like trying to kill a fly with a sledge hammer. You don’t kill the fly but you end up breaking all the furniture. …We cannot reduce women to equality. Equality is a step down for most women.” The crowd hissed at her in response.[15]

In 1977, Schlafly demonstrated outside the White House with a group of 150 anti-ERA activists. Their target that day was Rosalynn Carter, President Jimmy Carter’s wife. Schlafly and her followers were incensed that the First Lady had called legislators in Indiana urging them to ratify the amendment (an act that was also taken by First Lady Betty Ford). “State legislators across the country resent this improper White House pressure,” Schlafly said.[16] One of the demonstrators alongside Schlafly was 76-year-old Gilda Griffith. She claimed to have marched as one of the “original suffragettes” when she was 15 years old. However, she now believed “we should quit while we’re ahead. We’ve got equal pay for equal work and that’s enough!”[17]

The tension between the role of traditional homemaker and fierce political activist was noted by many commentators of the ERA battle. A critical 1974 Washington Post profile of Schlafly, for instance, remarked that “Schlafly is a walking contradiction. Her outward demeanor and dress is one of a feminine bridge playing, affluent housewife. Yet on the podium she comes on like a female George Wallace.”[18]

This account also exemplified the extent to which Schlafly was disliked by many in the press. According to Schlafly’s biographer, Carol Felsenthal, many reporters (who were more likely to be favorable toward the ERA) simply didn’t believe that her oppositional campaign was genuine; that she had an ulterior motive. “She’s a liar,” said Karen DeCrow, president of the National Organization for Women about Schlafly. Likewise, Sandy Hill of “Good Morning America” once asked Schlafly, in exasperation, “I would really like to know, personally, Mrs. Schlafly, what you get out of this campaign.”[19] Schlafly responded, “I don’t get anything out of it except a lot of abuse. And it has meant a tremendous amount of personal sacrifice to me.”[20]

But Schlafly, who heavily distrusted the media, “was not above exploiting it” either, Felsenthal wrote.[21] She was going to get her message out, one way or another—but she was never careless about her media appearances. “Mrs. Schlafly is a creature of the media,” wrote Walter Sharp, an Illinois journalist.[22] “She is careful to sit in just the right chair when she is going to be photographed” and is like “an eager actress” with her concern for proper lighting and ensuring she was “always wearing an affable smile.” Schlafly was “always on, she’s very serious about that image. She’s deadly serious about it, and that’s what makes her so dangerous,” Sharp said.[23]

Schlafly’s image-making skill was part of her national charm and crucial to the development of conservative women’s self-identity in the 1970s. Her followers saw themselves in her and considered Schlafly to be “Our Savior” and “Our Wonder Woman.”[24] Schlafly also imparted her media acumen to fellow activists at “training conferences.”[25] These were workshops where conservative women learned how to speak on camera, debate, develop self-awareness of their appearance to others, and, according to one attendee, learn “how to smile.”[26]

But for all the public criticism and pushback, it didn’t make a dent in the anti-ERA movement. And after a decade-long battle—and only three states shy of ratification—the ERA failed to enter the Constitution by the 1982 deadline. Schlafly and the anti-ERA forces convinced enough voters and state legislators to stop supporting the amendment, and in the process weakened the forward march of the women’s liberation movement.

On the day of the deadline, Schlafly woke up, grabbed the morning paper, and read the date out loud: “Today is Wednesday, June 30.”[27] All that was left to do now was to throw a party.

A Night of Celebration

Invitations had been sent out to friends, family, and close associates of Eagle Forum to celebrate the demise of the ERA. “Phyllis Schlafly and the members of Eagle Forum cordially invite you to participate in an Over the Rainbow Celebration,” the invite said.[28] Guests attended for $35-a-ticket (about $100 in today’s money.)[29]

When asked why the celebration was called “Over the Rainbow,” Schlafly said it was because “we’ve come through a storm and are looking for a bright new day.”[30] The ERA was over, she declared. “The American public won’t buy their product,” she said, referring to ERA proponents and feminists.

Among those to be “specially honored” that night were over 50 guests, including congressmen, religious leaders, generals, admirals, and several members of the National Review, a conservative magazine founded by William F. Buckley Jr. in 1955 (often credited with stimulating the conservative movement in post-war America).[31]

Noteworthy guests included the Rev. Dr. Jerry Falwell, a television evangelist, George Gilder, an economist who influenced the Reagan administration with his promotion of supply-side economics and authoring the “Bible” of the Reagan administration, Wealth and Poverty, and Paul Weyrich, co-founder of the DC-based conservative think tank The Heritage Foundation, and, with Falwell, the Moral Majority organization in 1979 (which helped launch the Christian Right into the mainstream of American politics). President Ronald Reagan also sent a congratulatory telegram to Schlafly.[32]

Predictably, Schlafly and the press butted heads on the day of the gala. Earlier in the day, a reporter asked her, “Do you think there are a lot of people who want to punch you in the nose?” Schlafly later remarked about the press commentary on her gala: “It just irritates them that I’m having a party. They can hardly stand it.”[33]

The night began with a cocktail reception, followed by a steak dinner. Music was always in the air. Pat Suzuki’s “I Enjoy Being a Girl” was overheard, along with spontaneous breakouts of musical renditions mocking the attendees’ feminist opponents. One of the compositions, an adaptation of the musical “Kiss Me Kate,” targeted Eleanor Smeal, president of the National Organization for Women.

“Where are you Ellie?”

“I’m sorry to tell you that your arguments were smelly.”[34]

Another verse was aimed at Ms. Magazine founder and feminist activist Gloria Steinem.

“Where are you Gloria?”

“Still pedaling your life style to housewives in Peoria?”[35]

The Dr. Rev. Falwell, praising Schlafly, said that she “has succeeded in doing something nobody has ever done.” Schlafly “mobilized the conservative women of this country into a powerful political unit.”[36]

Toward the end of the night, speeches were given by select guests and capped off by a 14-minute address from Schlafly, who called for a “mighty movement” that will “set America on the right path.”[37]

The dinner ended with the crowd standing and singing along to Irving Berlin’s “God Bless America.”[38]

ERA Activists Continue the Struggle

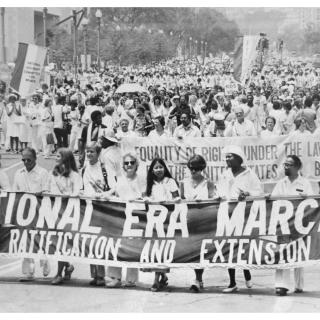

While Schlafly celebrated at the Shoreham, Eleanor Smeal organized a rally in mourning at Lafayette Park, across the White House.[39] Nearly four years earlier, Smeal helped organize one of the largest parades for feminism in history. On that day, Smeal, beaming over the west steps of the Capitol building, shouted at the top of her lungs: “Phyllis Schlafly, eat your heart out!”[40] But on June 30, she led a different type of rally, led under the name, “We Will Continue Until Justice Is Ours.”[41]

That morning, spray-painted graffiti spelling out the words “ERA LIVES” and “ERA Will Never Die” were spotted across District sidewalks and buildings. The former phrase was even spotted on the Supreme Court building.[42] And in the afternoon, around 2,000 demonstrators, dressed in green and white colors meant to symbolize the ERA, sang the refrain “We will never give up, we will never give in” at Lafayette Park.[43] “We are ending this campaign stronger than we began,” said Smeal. “We are a majority. …We are not going to be reduced again to the ladies’ auxiliary.”[44]

When asked to explain why the ERA was defeated, Smeal discounted the frequent charges against the amendment by its opponents—such as a military draft for women and the emergence of unisex bathrooms—and instead targeted the efforts of big businesses.[45] (To this day, Gloria Steinem insists that the ERA failed due to “the insurance industry and other economic interests that stood to lose billions if the ERA passed,” not due to Schlafly and her followers. Smeal concurs.)[46] But Smeal nonetheless vowed to keep fighting for the ERA: “We’ll keep going. We have no other agenda.”[47]

Yet with a congressional makeup more conservative than the one that originally passed the amendment, the likelihood of an ERA comeback was slim.

The amendment was reintroduced again in Congress in 1983. But this time, it failed to pass the House. It was reintroduced again in each session of Congress from 1985 to 1992, only to be held in committee.[48] But despite the setback, local activists continued to lobby individual states to ratify the amendment, even as the original deadline lapsed.

In 2020, Virginia became the 38th state, following Nevada (2017) and Illinois (2018), to ratify the ERA—a symbolic victory for the generations of activists.[49] And in a remarkable move, on March 17, 2021, the House voted to remove the ratification deadline from the original amendment. Activists hope that if the resolution passes the Senate, the ERA will enter the Constitution.[50]

Footnotes

- ^ “History,” Omni Shoreham Hotel, accessed April 4, 2022, https://www.historichotels.org/us/hotels-resorts/omni-shoreham-hotel-wa….

- ^ Ellen Goodman, “Phyllis Schlafly Throws a Party,” Washington Post, June 15, 1982; Elisabeth Bumiller, “Schlafly’s Gala Goodbye to ERA,” Washington Post, July 1, 1982.

- ^ Lynn Rosellini, “Victory Is Bittersweet for Architect of Amendment’s Downfall,” New York Times, July 1, 1982.

- ^ Donald Critchlow, Phyllis Schlafly and Grassroots Conservatism: A Woman’s Crusade (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2005), 256.

- ^ Carol Felsenthal, The Sweetheart of the Silent Majority: The Biography of Phyllis Schlafly, (Chicago: Regnery Gateway, 1982), 240.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Phyllis Schlafly, “What’s Wrong with ‘Equal Rights’ for Women?,” Phyllis Schlafly Report, February 1972.

- ^ Fred Fejes, Gay Rights and Moral Panic: The Origins of America’s Debate on Homosexuality (New York: Palgrave MacMillan, 2008), 1-10.

- ^ Kirsten Delegard, “‘It Takes Women to Fight Women’: Women Suffrage and the Genesis of Female Conservatism in the United States,” in Women of the Right: Comparisons and Interplay across Borders, ed. Kathleen M. Blee and Sandra McGee Deutsch (University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press, 2012), 211-25.

- ^ Erin M. Kempker, Big Sister: Feminism, Conservatism, and Conspiracy in the Heartland (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2018), 24.

- ^ Ibid., 113.

- ^ Felsenthal, The Biography of Phyllis Schlafly, 232.

- ^ Critchlow, Phyllis Schlafly, 217.

- ^ Ibid., 221.

- ^ Sally Quinn, “Phyllis Schlafly: Sweetheart of the Silent Majority,” Washington Post, July 11, 1974.

- ^ “Anti-ERA Protest Aimed at First Lady,” Washington Post, February 5, 1977.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Quinn, “Phyllis Schlafly."

- ^ Felsenthal, Sweetheart of the Silent Majority, 298-99.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Ibid., 299.

- ^ Ibid., 299-300.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Ibid., x.

- ^ Ibid., 267.

- ^ Ibid., 267-68; Kempker, Big Sister, 72.

- ^ Rosellini, “Victory Is Bittersweet.”

- ^ Goodman, “Phyllis Schlafly."

- ^ Rosellini, “Victory is Bittersweet."

- ^ Bill Peterson, “Some Come to Bury, Some to Praise ERA,” Washington Post, June 30, 1982.

- ^ Judy Mann, “The Winners,” Washington Post, June 30, 1982.

- ^ Bumiller, “Schlafly’s Gala."

- ^ Rosellini, “Victory is Bittersweet."

- ^ Bumiller, “Schlafly’s Gala."

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Rosellini, “Victory Is Bittersweet."

- ^ Bumiller, “Schlafly’s Gala."

- ^ Phyllis Schlafly Eagles, “Over the Rainbow Dinner: The End of ERA, 1982,” YouTube video, 1:14:27, June 30, 2017, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=iQEK3VYfsxY.

- ^ Patricia McCormick, “June 30, 1982: The Day the ERA Died,” United Press International, June 30, 1982; Sandra R. Gregg and Bill Peterson, “Backers, Foes Mark End of ERA Battle,” Washington Post, July 1, 1982.

- ^ Rick MacArthur and Adrienne Washington, “Almost as One, They Came by Thousands,” Evening Star, July 10, 1978.

- ^ Lyle Denniston, “No Eulogy for ERA: Foes Clapping, Pros Mapping Comeback,” Baltimore Sun, July 1, 1982.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Gregg and Peterson, “Backers, Foes.”

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ McCormick, “June 30, 1982."

- ^ Eleanor Smeal and Gloria Steinem, “Steinem and Smeal: Why ‘Mrs. America” is Bad for American Women,” Los Angeles Times, July 30, 2020, https://www.latimes.com/entertainment-arts/tv/story/2020-07-30/steinem-….

- ^ Bill Peterson, “ERA Leaves in Wake Potent Political Force Set for New Battles,” Washington Post, June 27, 1982.

- ^ “Chronology of the Equal Rights Amendment, 1923-1996,” National Organization for Women, accessed April 4, 2022, https://now.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/01/Chronology-of-the-Equal-Righ….

- ^ Timothy Williams, “Virginia Approves the E.R.A., Becomes the 38th State to Back It,” New York Times, January 15, 2020, https://www.nytimes.com/2020/01/15/us/era-virginia-vote.html.

- ^ ‘Three-State Strategy’ Legislation,” Alice Paul Institute, accessed April 11, 2022, https://www.equalrightsamendment.org/incongress.

![Sketch of the mythical fuan by Pearson Scott Foresman. [Source: Wikipedia]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2023-10/Goatman_Wikipedia_Faun_2_%28PSF%29.png?h=64a074ff&itok=C9Qh-PE1)