Ford's Theatre's Forgotten Tragedy

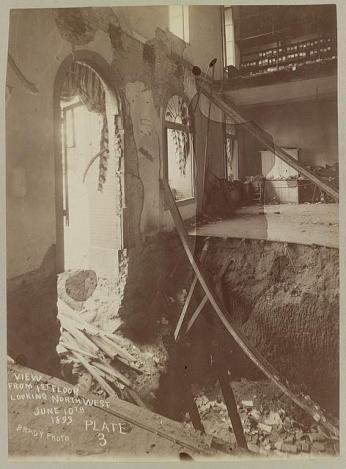

On the morning of June 9, 1893, around 400 clerks from the Record and Pension Bureau of the US War Department went to work at what once was Ford’s Theatre, as they had for almost three decades before. It was an ordinary day, save for some construction. For the past several months, workers had been excavating the building’s basement to fit the building with electricity – yet another change for the one-time entertainment space, which had been converted into a federal office building following Lincoln’s assassination.

No more than an hour after work had begun, tragedy struck.[1] As Record and Pension Bureau supervisor Thomas Adams told the Evening Star, “I was on the lower floor in the hallway when the crash came… I heard what sounded like an explosion, and the door slammed together and was so tightly closed that I could not open it. Then came the bricks, timbers and mortar. When the noise was finished I could hear the groans of the injured, and those who were not injured were screaming for assistance.”[2]

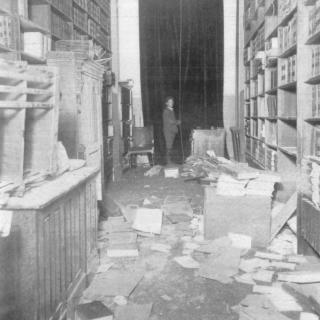

Initially, the clerks struggled to make sense of what had happened, but as the dust settled, it was clear. The building’s third floor had collapsed, taking the second and first floors down with it. “The two floors had been cut away from the wall as closely as if done with a knife… thirty or forty feet below was a mass of building material, girders, beams and bricks. Inside that mass it was known that there were men.”[3]

Those men who were not trapped beneath the debris scrambled to escape the unstable building. Men jumped from windows, crawled from the rubble, and in one case, slid down the side of the building on a firehose. Alarm bells immediately went up around the city, calling all firetrucks and ambulances to the scene. Doctors and nurses rushed to the building and even the army and navy were dispensed to the site of the disaster. Emergency workers and neighborhood volunteers dug victims out of the wreckage. The victims were so mangled and covered in grime that sometimes it was impossible to tell if the people were dead or alive. As one observer put it, “in many cases the semblance to humanity was gone.”[4]

A crowd of thousands gathered, including family and friends of clerks who they had sent off to work that morning with no idea of the danger awaiting them. When a clerk was brought out dead or seriously injured, screams and wails erupted from the crowd. Some onlookers even fainted at the sight of the injuries, which were akin to a battlefield.[4] When a man was rescued alive or with only minor injuries, the crowd broke out in cheers and applause. It took nearly all day to clear away the rubble and rescue all the clerks. All told, 22 men were dead and over 50 were injured.[5]

Many heroes emerged from the horror that day. Shopkeepers and neighbors opened their doors to serve as temporary hospitals and shared food, water, and other supplies with victims and rescuers.[6] One woman who lived next door to the building, Mrs. Kosack, was so fervent in her rescue efforts that she fell off of a ladder in her home while trying to reach the men in the adjacent building. When her husband found her lying on the floor with a broken arm, she urged him to leave her and help the clerks.[7] Another onlooker, Yorick Smith, a Black contractor, was driving past in his buggy when he heard the screams and saw people jumping from the building. He ran into the building to help, and upon seeing the dire scene, rushed to the nearest phone and called for doctors. Then he got back in his buggy and drove doctors to the scene.[8]

Perhaps the most notable hero of the day was Basil Lockwood, a young Black man around twenty years old, who scaled a telephone pole to Ford’s third floor and helped at least ten men down to safety.[9] For his heroism, the clerks later gifted Lockwood a gold watch, and eventually even a job “in the same office and room with the men he rescued.”[10]

(It should be noted that not all Washingtonians were so selfless as Kosack, Smith, and Lockwood. While the rescue effort was underway, “a physician stopped his work long enough to hunt up a Star reporter to tell him his name and ask that it be used as one of those who was on the scene from the first and did noble work. The name was not recorded.”[11])

As horrible as the accident had been, it was all the more tragic considering that it may have been preventable had warning signs been heeded. Clerks and construction workers at the site had long warned officials of the dangerous conditions[12] and some had taken it upon themselves to plan and practice an escape route which involved climbing out of the building on pipes and overhangs and jumping to an awning below.[13]

The building had been condemned three times since the Record and Pension Bureau began working there. Yet, the office was never moved.[14] And, worse, there were other federal buildings in Washington that were notoriously unsafe, including the government printing office and the war records office. It was somewhat of an open secret.[15] Federal employees in these buildings frequently complained of their conditions to everyone from their coworkers to Congress to no avail.[16] As one journalist put it, “It appears to be almost as dangerous for a man to serve his country now in a clerical capacity as it was to enlist in the army.”[17]

On the day of the accident, a Black man working on the basement excavation told the Evening Star that he had expressed concern about the building’s safety just one day before the disaster. “I told [my employer] yesterday that the archway would fall, for every time any one walked over the floor it would bend. I tell you I was scared, and got out just as quick as I could. There were twenty men at work with me. ‘Deed I don’t know what became of them.”[18]

After the victims were saved and the dead identified, government officials began to investigate the cause of the collapse. They concluded that the basement excavation for electricity had weakened the building’s internal supports.[19] John T. Ford, the owner of the original Ford’s Theatre, released a statement claiming that he was not at fault. The Evening Star published his statement, which read, “The terms used by many of the press calling the theater a “death trap,” an “eggshell,” &c., are not to be justified… Associated as my name has been with the property, and assuming all responsibility for the part of it that I built, which at this writing remains intact and unimpaired, I beg the publication of this explanation.”[20]

One of the first people to be blamed for the disaster was Colonel Fred C. Ainsworth, the head of the Record and Pension Bureau. He was a notoriously difficult boss, so he was an easy target.[21] At the coroner’s inquest into the clerks’ cause of death, the brother of one of the deceased “pushed his way through the crowd where Col. Ainsworth was sitting, pointed his finger at the colonel, and said in a voice trembling with passion but which could be heard in every corner of the hall: ‘You are intimidating every witness here, and I hold you personally responsible for my brother’s murder.’” The hall broke into a commotion, with clerks calling Ainsworth a murderer and demanding that he be hanged.[22]

Some defended Ainsworth, saying that the building’s construction was beyond his responsibilities as head of the Record and Pension Bureau.[23] Ainsworth, along with the building’s contractor, engineer, and superintendent were all charged with criminal negligence and manslaughter by a grand jury. All four pleaded not guilty and were acquitted.[24]

Victims suffered more than physical injuries. Many lost their ability to work and provide for their families. Those who could not return were kept on the payroll, and continued to be paid by the Record and Pension Bureau.[25] Congress also appropriated funds to pay $5000 each to the survivors and families of the deceased.[26] Many victims also felt the psychological impact from the collapse for months and years after the incident. Several months after the collapse, while at work in their new office building, “the clerks on the third floor felt the floor tremble and vibrate, and this came very near causing a stampede.”[27]

Beyond the horror of the experience, the collapse at Ford’s raised questions about workers’ rights, industrialization, and federal control over local Washington issues that would define labor and politics in the city in the century that followed.

In Washington and in cities around the country, officials rushed to inspect federal buildings.[28] The American Federation of Labor and the Knights of Labor cited the Ford’s collapse as a reason to change the way the federal government contracted labor. The contract system at use at that time gave building contracts to go to the lowest bidder, which led to irresponsible contractors, poor materials, and dangerous working conditions, both for the contractors and the employees who occupied the buildings. The AFL and Knights of Labor recommended that the government replace the contract system by employing its own government workers.[29] It would take several decades for the federal government to make amends to the contract system, with the passage of the Davis-Bacon Act in 1931.

Many journalists and citizens used this incident as an example of federal officials’ “cheese-paring” when it came to Washington’s needs. One disgruntled citizen wrote in a letter to the editor of The Evening Star, “It is a pity that the direct government of the District of Columbia could not be arranged so that it would be in the hands of men in whom outside politics would not destroy interest in the welfare of the District and its inhabitants.”[30] It is unlikely the author lived to see a change on that front – Washington did not gain home rule until 1973.

Opinions varied on what should be done with the Ford’s Theatre building after the collapse. Some thought it should be razed and its tragic past forgotten. Others thought it should become a memorial, a museum, or even a public library.[31] However, the final determination was to return the building to the bureaucrats. Less than a year after the collapse, Colonel Ainsworth and the clerks moved back into the newly renovated building, where the office stayed until 1928.[32]

In 1933, the National Park Service took control of the building, and in 1968 it reopened as a theater once more. The floors that had once fallen through were intentionally torn down, with the interior restored to the way it looked during Lincoln’s time. Today it is an operating theater and a museum of Lincoln’s life and assassination. Visitors go there to remember and honor Lincoln’s life and legacy, but few are aware that on that very same ground, 22 government workers lost their lives working to better their country, just like Lincoln.[33]

Footnotes

- ^ “Frightful Disaster, Hundreds of Clerks Buried in a Ruined Building,” The Evening Star, June 9, 1893.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ CITATION HERE

- ^ “Twenty-Two Lives Lost,” New York Tribune, June 10, 1893.

- ^ “Frightful Disaster.”

- ^ “How Mrs. Kosack Was Injured,” The Evening Star, June 14, 1893.

- ^ “Frightful Disaster.”

- ^ “This Week in Washington,” The National Tribune, June 13, 1893.

- ^ “Basil Lockwood’s Assignment,” The Evening Star, October 24, 1893.

- ^ “Frightful Disaster,” The Evening Star, June 9, 1893.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ “Twenty-Two Lives Lost.”

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ “Buildings examined” The Evening Star, June 22, 1893.

- ^ “What Papers Say” The Evening Star, June 12, 1893.

- ^ “Frightful Disaster.”

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ “What Papers Say.”

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ “Col Ainsworth and the clerks,” The Evening Star, June 19, 1893.

- ^ “‘Hang Him! Hang Him!’ The Demonstration Against Col. Ainsworth at the Inquest,” The Evening Star, June 13, 1893.

- ^ “Who is responsible? What the newspapers say about the ford’s theater disaster,” The Evening Star, June 13, 1893.

- ^ “All four arraigned,” The Evening Star, July 28, 1893.

- ^ “Ford’s Theater Victims,” The Evening Star, October 16, 1893.

- ^ “Five thousand dollars: that sum to be given to each of ford’s theater victims,” The Evening Star, July 5, 1894.

- ^ “Several Accidents Cause a Commotion at the Union Building Saturday,” The Evening Star, August 28, 1893.

- ^ “This Week in Washington,” The National Tribune, June 13, 1893.

- ^ “The Competitive Contract System,” The Evening Star, June 15, 1893; “Against contracts,” The Evening Star, June 24, 1893.

- ^ “Who is responsible?”

- ^ “Against the Building: A Resolution Aimed at the Occupancy of Ford’s Old Theater,” The Evening Star, December 20, 1893.

- ^ “Pronounced Safe: Ford’s Theater Building to be Again Occupied,” The Evening Star, July 31, 1894.

- ^ “Ford’s Theatre History,” Ford’s Theatre, Accessed September 12, 2022.

![Sketch of the mythical fuan by Pearson Scott Foresman. [Source: Wikipedia]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2023-10/Goatman_Wikipedia_Faun_2_%28PSF%29.png?h=64a074ff&itok=C9Qh-PE1)